Twenty Poems of Edward de Vere: Note on Sources & Parallels, Key to Abbreviations, and Works Cited

The Note on Sources, Titles, and Presentation of Parallels, the Key to Abbreviations, and the Bibliography of Works Cited (set forth below) are part of the 2018 website presentation of early poems by Edward de Vere. See the Introduction, which provides access to the poems themselves and a printable pdf version of the entire presentation. The poems may also be accessed from the list below at the end of the Note on Sources, Titles, and Presentation of Parallels.

Note on Sources, Titles, and Presentation of Parallels

Each poem is presented in plain text, with line numbering, followed by annotations in which bolded red is used for words and phrases drawn from these de Vere poems for comparison to parallel passages in the Shakespeare poems and plays. Bolded black is used for our own editorial commentary (though not in Appendices A and B to Poems 4 and 18), and plain text is used for words and phrases from the Shakespeare poems and plays (italicized where useful to highlight especially notable textual overlaps between these de Vere poems and the Shakespearean passages).

The parallels set forth in the annotations are divided into two broad categories: first the “strongest” parallels to each poem and then “additional” parallels to that poem. Within each category, the parallels are listed not in order of perceived strength, but simply following the line numbering of the parallel passages identified in each de Vere poem.

The “strongest” parallels are those which, even viewed in isolation, seem to us especially suggestive of common authorship. The “additional” parallels are those which seem to us not as strong for various reasons but still significant, especially in a cumulative sense. As Looney noted, these poems contain many “minor points of similarity, which though insignificant in themselves, help to make up that general impression of common authorship which comes only with a close familiarity with [them] as a whole” (1920, 161). But we hasten to add that we have not tried to identify all “minor points of similarity.” Even with regard to the “additional” parallels, we have presented only those which we feel are in some way significant, noteworthy, and interesting.

There is doubtless ample room for reasonable debate (which we welcome) about whether any given parallel properly belongs in one category or the other — or perhaps, in some cases, lacks the significance we perceived. At the same time, we have doubtless missed some parallels altogether, or some telling expansions or elaborations of ones that are presented here. We welcome constructive critical feedback on all aspects of this presentation. A great deal of subjective discretion has likewise gone into defining the scope of each of the parallels. We make no claim of numerical precision.

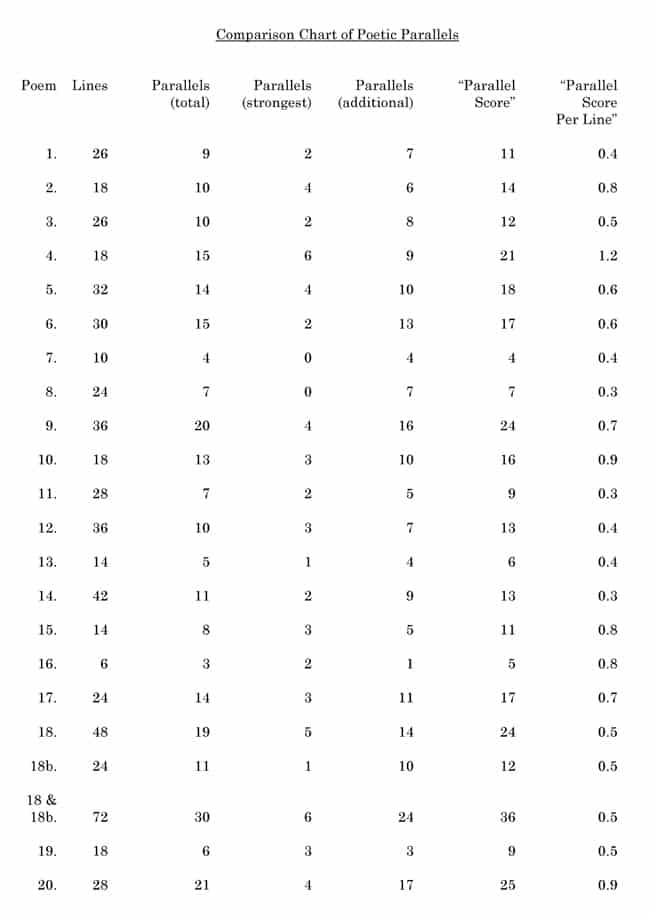

Thus, we are unsure what value the following numbers may have. But for readers who may be interested, we have identified in these twenty poems a total of 232 passages, each containing one or more (often many) parallels in the works of Shakespeare. Many of these passages constitute elaborate sets or clusters of parallels, echoing multiple Shakespearean passages.

We generally use the terms “parallel” and “echo” a bit loosely, to refer either to each de Vere parallel passage (identified by a line number or numbers) or to each separate Shakespearean passage echoing or paralleling that line or passage. But the numbers summarized here refer strictly and conservatively to the de Vere parallel passages. Thus, it is important to note, the total number of parallels could be said to be much larger. But we do not seek to hype or artificially inflate the numbers.

Under these conservative definitions, we have identified 56 parallel passages as the “strongest” and the remaining 176 as “additional.” The number of such passages identified in each poem varies widely, from three (No. 16) to thirty (No. 18, including 18b). The average is 11.6 per poem. The poems contain a total of 520 lines and they also vary greatly in length, from No. 16 (six lines) to No. 18-18b (72 lines). One would expect a longer poem to have more parallels. The strongest parallels also deserve more weight, perhaps twice that of the others. One might thus calculate a “parallel score” for each poem by multiplying the number of strongest parallels by two, then adding the number of additional parallels.

Under this concededly subjective and debatable comparison, No. 18-18b (scoring 36) appears to have the greatest absolute correspondence with the Shakespeare canon. No. 4 has the strongest “score per line” (1.2). No. 7 appears weakest in an absolute sense (scoring 4), and Nos. 8, 11, and 14 the weakest “per line” (0.3). Yet all four of the latter poems still exhibit fascinating parallels to Shakespeare — including one noted in 1910 by a leading Stratfordian scholar (see No. 11, lines 3-4).

With 232 passages containing significant Shakespearean parallels, divided by a total of 520 lines, it appears there is at least one such passage for every two or three lines in this early de Vere poetry — and about one unusually strong parallel for every ten lines. (Update: Professor Stritmatter’s published study identifies a considerable number of additional parallels.)

Below is a chart summarizing and comparing the numbers for all twenty poems:

We generally do not try to credit specific scholars with regard to each specific parallel noted. Doing so would introduce excessive detail and clutter and would risk unintended omissions. We credit the past scholarly commentaries on the parallels to each poem generally, following the text of each poem. We have certainly relied upon those, in some cases building upon them, and are very grateful for them. We welcome information about any additional commentaries we may have missed. We do, on occasion, mention certain scholars in relation to specific parallels, where that information may be of particular interest.

Titles for all the poems are suggested in this presentation, not necessarily following those in the early manuscript and print sources, where titles may have been crafted or chosen by an editor or transcriber and may well not reflect de Vere’s own choice. We also do not generally follow the titles provided in past modern editions like Grosart’s or Looney’s. May did not suggest any titles, except to note the manuscript titles of Nos. 13 and 18.

While we cannot be confident that de Vere himself chose or intended titles for any of the poems, we feel reasonably confident in assigning the text of each poem to him. Titles are a great convenience, helping readers remember and keep track of the poems. Thus, we use all or part of the first line of text of each poem for the title, or some other line of text that captures its overall theme. We adopt the apt title for No. 4 suggested by Prechter (149). The only exception to the foregoing rule is that we do accept the manuscript title of No. 13 (though not found in that poem’s text), because it seems very apt.

Following each poem’s number and title as given in this presentation, we provide the text from relevant original sources, largely following Looney’s 1921 edition (hereinafter “Looney”), if available therein. Looney in turn relied heavily on Grosart’s 1872 edition (394-429). We are also guided by the thorough scholarship evident in May’s editions (1975; 1980, 25-42, 66-84, 118-23; 1991, 270-86). Spelling and punctuation are silently modernized and harmonized for the convenience of readers, largely guided by Looney.

After the text of each poem, we indicate its sources; how the poem was listed by May (from #1 to #16) among those he viewed as very likely by Oxford (1980, 25-37, 67-79; 1991, 270-81), or that he viewed as “possibly” so (the latter abbreviated “PBO” #1 to #4) (1980, 38-42, 79-83; 1991, 282-86); each poem’s stanzaic and metrical structure; the title (if any) provided by Looney; sources providing past commentaries on parallels; and clarifications of the text, as needed.

A significant instance where we follow May, for the purpose of our conservative approach explained in the Introduction (Selection of Poems), is with regard to No. 11. May did not accept the first four and last four lines of No. 11 as given by Grosart and Looney (compare Grosart 407-09, and Looney 10-11, with May 1980, 33; 1991, 277-78). Thus, the first line of No. 11 given here and by May — and the title we use — is “When wert thou born, Desire?” (not “Come hither, shepherd swain!”).

As explained in the Introduction (Selection of Poems), taking a conservative approach, we omit poems that May omitted entirely from his editions. We do, however, include the four stanzas of No. 18b which May included in his 1975 article, but which he did not attribute to de Vere as part of No. 18, even as he accepted the eight stanzas of No. 18 itself as “possibly” by de Vere (our reasons are explained in Appendix B). We also include lines 1-16 (not accepted as Oxfordian by May) in No. 20 (May accepted lines 17-28 as “possibly” by de Vere).

Grosart and Looney, on the other hand, were apparently not aware that Oxford could be credited with Nos. 12, 13, or 18-18b. As noted in the Introduction (Evaluating the Poetic Parallels), it is interesting that while May has criticized Looney and other Oxfordians for detecting some Shakespearean echoes in poems mistakenly (in May’s view) credited to de Vere (2004, 222, 224-25), the poems Looney missed include some (e.g., No. 18) that appear to be among the richest in parallels of this entire corpus. Thus, as we noted, Looney’s pioneering insights have been corroborated and strengthened by poems identified by May, which Looney did not even consider.

Following is a list of all 20 poems and the key modern sources providing their text (Hannah’s 1870 edition omits any mention of Nos. 12-14, 18b, and 20, and references, 241-42, but does not provide the text of Nos. 2-9, 15, and 17; Grosart’s 1872 edition omits Nos. 12-13, 18-18b, and 20; Looney’s 1921 edition omits Nos. 12-13, 18-18b, and part of No. 20):

- “The Labouring Man That Tills the Fertile Soil” (Hannah 145-46; Grosart 422-23; Looney 14-15; May 1980, 25; 1991, 270-71).

- “Even as the Wax Doth Melt” (Grosart 396-98; Looney 31-32; May 1980, 26; 1991, 271).

- “Forsaken Man” (Grosart 403-04; Looney 27-28; May 1980, 26-27; 1991, 271-72).

- “The Loss of My Good Name” (Grosart 401-02; Looney 22-23; May 1980, 27-28; 1991, 272-73).

- “I Am Not as I Seem to Be” (Grosart 395-96; Looney 29-30; May 1980, 28-29; 1991, 273-74).

- “If Care or Skill Could Conquer Vain Desire” (Grosart 399-400; Looney 34-35; May 1980, 29-30; 1991, 274-75).

- “What Wonders Love Hath Wrought” (Grosart 410; Looney 36; May 1980, 30; 1991, 275).

- “The Lively Lark Stretched Forth Her Wing” (Grosart 405-06; Looney 7; May 1980, 30-31; 1991, 275-76).

- “The Trickling Tears That Fall Along My Cheeks” (Grosart 394-95; Looney 25-26; May 1980, 31-32; 1991, 276-77).

- “Fain Would I Sing But Fury Makes Me Fret” (Hannah 144-45; Grosart 421-22; Looney 24; May 1980, 32-33; 1991, 277).

- “When Wert Thou Born, Desire?” (Hannah 142-43; Grosart 407-09; Looney 10-11; May 1980, 33; 1991, 277-78).

- “Winged With Desire” (May 1980, 34-35; 1991, 278-79).

- “Love Compared to a Tennis-Play” (May 1980, 35; 1991, 279-80).

- “These Beauties Make Me Die” (Grosart 417-19; Looney 5-6; May 1980, 35-37; 1991, 280-81).

- “Who Taught Thee First to Sigh?” (Grosart 413; Looney 4; May 1980, 37; 1991, 281).

- “Were I a King” (Hannah 147; Grosart 426-27; Looney 38; May 1980, 37; 1991, 281).

- “Sitting Alone Upon My Thought” (Echo Verses) (Grosart 411-12; Looney 2-3; May 1980, 38-39; 1991, 282-83).

- “My Mind to Me a Kingdom Is” (No. 18 appears in Hannah 149-50, attributed to Dyer, and in May 1975, 391-92; 1980, 39-40; 1991, 283-84; No. 18b appears in Rollins 1929, 1: 225-31, attributed to Dyer, and in May 1975, 392-93, unattributed).

- “If Women Could Be Fair and Yet Not Fond” (Hannah 143-44; Grosart 420; Looney 37; May 1980, 40-41; 1991, 284).

- “Cupid’s Bow” (Looney 72-73, lines 1-16 only; May 1980, 41-42; 1991, 284-86, attributing lines 1-16 to Churchyard).

Return to the Introduction.

Key to Abbreviations

A&C = Anthony and Cleopatra (While often given as “Antony” and Cleopatra, the accurate and authentic title, respecting its source in the First Folio, is in fact Anthony and Cleopatra, as noted in Professor Michael Delahoyde’s superb critical edition (2015, vii). See Bibliography of Works Cited, below.)

All’s Well = All’s Well That Ends Well

As You = As You Like It

Caes. = Julius Caesar

Cor. = Coriolanus

Cym. = Cymbeline, King of Britain

Dream = A Midsummer Night’s Dream

Edw. III = Edward III

Errors = The Comedy of Errors

Ham. = Hamlet, Prince of Denmark

1 Hen. IV = King Henry IV, Part 1

2 Hen. IV = King Henry IV, Part 2

Hen. V = King Henry V

1 Hen. VI = King Henry VI, Part 1

2 Hen. VI = King Henry VI, Part 2

3 Hen. VI = King Henry VI, Part 3

Hen. VIII = King Henry VIII

John = King John

Kins. = The Two Noble Kinsmen

Lear = King Lear

LLL = Love’s Labour’s Lost

Lover’s Comp. = A Lover’s Complaint

Lucrece = The Rape of Lucrece

Mac. = Macbeth

Meas. = Measure for Measure

Merch. = The Merchant of Venice

MS(S) = manuscript(s)

Much = Much Ado About Nothing

OED = Oxford English Dictionary (see Bibliography of Works Cited, below)

Oth. = Othello, the Moor of Venice

Pass. Pilg. = The Passionate Pilgrim

PBO = “possibly by Oxford” (in the opinion of May, 1980, 38-42, 79-83)

Per. = Pericles, Prince of Tyre

Phoenix = The Phoenix and the Turtle

Rich. II = King Richard II

Rich. III = King Richard III

R&J = Romeo and Juliet

Shrew = The Taming of the Shrew

Sonnets = Shake-speare’s Sonnets

Tem. = The Tempest

Timon = Timon of Athens

Titus = Titus Andronicus

Troil. = Troilus and Cressida

Twelfth = Twelfth Night, or What You Will

Two Gent. = The Two Gentlemen of Verona

Venus = Venus and Adonis

Win. = The Winter’s Tale

Bibliography of Works Cited

Anderson, Mark. “Shakespeare” By Another Name: The Life of Edward de Vere, Earl of Oxford, the Man Who Was Shakespeare. Gotham, 2005 (available on Amazon.com).

Arber, Edward, ed. The Arte of English Poesie (anonymous; widely attributed to George Puttenham). London: Richard Field, 1589. Reprinted (Arber ed.), London: Bloomsbury, 1869 (available in Google Books). Reprinted as The Art of English Poesy by George Puttenham: A Critical Edition (Frank Whigham & Wayne A. Rebhorn eds.), Cornell University Press, 2007.

Argamon, Shlomo, Kevin Burns & Shlomo Dubnov, eds. The Structure of Style: Algorithmic Approaches to Understanding Manner and Meaning. Springer, 2010.

Barrell, Charles Wisner. “The Playwright Earl Publishes ‘Hamlet’s Book’.” Shakespeare Fellowship Quarterly (U.S.), v. 7, no. 3, pp. 35-42, July 1946.

_____. “Proof That Shakespeare’s Thought and Imagery Dominate Oxford’s Own Statement of Creative Principles: A Discussion of the Poet Earl’s 1573 Letter to the Translator of ‘Hamlet’s Book’.” Shakespeare Fellowship Quarterly (U.S.), v. 7, no. 4, pp. 61-69, Oct. 1946.

Bennett, Nicola & Richard Proudfoot. See Proudfoot & Bennett.

Brazil, Robert Sean & Barboura Flues, eds. “Poems and Lyrics of Edward de Vere.” 2002 (former “Elizabethan Authors” website no longer available; now available here on Mark Andre Alexander’s “Shakespeare Authorship Sourcebook” website).

Burns, Kevin, Shlomo Argamon & Shlomo Dubnov. See Argamon, Burns & Dubnov.

Cardano [Cardanus], Girolamo. De Consolatione [Cardanus Comforte]. Venice, 1542. Reprinted (Thomas Bedingfield trans.), London: Thomas Marsh, 1573 (available in Google Books). Reprinted (rev. ed.), London: Thomas Marsh, 1576.

Chambers, Edmund K., ed. The Tragedy of Hamlet, Prince of Denmark. Boston: Heath, 1895 (available in Google Books).

Chaski, Carol. “Who’s at the Keyboard? Authorship Attribution in Digital Evidence Investigations.” International Journal of Digital Evidence, v. 4, no. 1, Spring 2005, pp. 1-11.

Chiljan, Katherine, ed. Letters and Poems of Edward, Earl of Oxford. N.p., 1998.

Courthope, William J. A History of English Poetry (in 6 vols. 1895–1910). Volume 2, New York: Macmillan, 1897 (available in Google Books).

Craig, Hardin. “Hamlet’s Book.” Huntington Library Quarterly Bulletin, no. 6, Nov. 1934, pp. 15-37.

Cutting, Bonner Miller. “Edward de Vere’s Tin Letters.” Shakespeare Oxford Fellowship, Oct. 14, 2017 (conference presentation) (posted on YouTube Jan. 22, 2018).

Delahoyde, Michael, ed. Anthony and Cleopatra. Oxfordian Shakespeare Series, 2015 (available on Amazon.com).

Dubnov, Shlomo, Shlomo Argamon & Kevin Burns. See Argamon, Burns & Dubnov.

Eagan-Donovan, Cheryl. “Looney, the Lively Lark, and Ganymede: A Closer Look at the Poetry of Edward de Vere.” Shakespeare Oxford Fellowship, Oct. 14, 2017 (conference presentation) (posted on YouTube March 23, 2018).

Edwards, Richard, ed. (see also Rollins ed. 1927). The Paradise of Dainty Devices [The paradyse of daynty deuises, aptly furnished, with sundrie pithie and learned inuentions: deuised and written for the most part, by M. Edwards, sometimes of her Maiesties chappel: the rest, by sundry learned gentlemen, both of honour, and woorshippe. viz. S. Barnarde. E.O. L. Vaux. D.S. Iasper Heyvvood. F.K. M. Bevve. R. Hill. M. Yloop, vvith others]. London: [R. Jones for?] Henry Disle [“dwellyng in Paules Churchyard, at the south west doore of Saint Paules Church, and are there to be sold”], 1576. Edited by Richard Edwards (1525–66). Reprinted (Hyder Edward Rollins ed.), Harvard University Press, 1927.

Elliott, Ward E.Y. & Robert J. Valenza. “Oxford by the Numbers: What Are the Odds That the Earl of Oxford Could Have Written Shakespeare’s Poems and Plays?” Tennessee Law Review, v. 72, no. 1, pp. 323-96, 2004.

_____. “The Shakespeare Clinic and the Oxfordians.” Oxfordian, v. 12, pp. 138-67, 2010.

England’s Helicon. London: John Flasket, 1600. Reprinted (Arthur H. Bullen ed.), London: Lawrence & Bullen, 1887, rev. 1899 (available in Google Books), and Harvard University Press (Hugh Macdonald ed.), 1949, 2d printing 1962 (edited from 1600 edition with additional poems from 1614 edition).

Flues, Barboura & Robert Sean Brazil. See Brazil & Flues.

Fowler, William Plumer. Shakespeare Revealed in Oxford’s Letters. Randall, 1986 (available on Amazon.com).

Gascoigne, George. See Miller, ed., A Hundreth Sundrie Flowres.

Goldstein, Gary. “Is This Shakespeare’s Juvenilia?” In Goldstein, Reflections on the True Shakespeare, Laugwitz Verlag, 2016 (Neues Shake-speare Journal, special issue no. 6) (available on Amazon.com), ch. 4, pp. 45-69.

_____. “Assessing the Linguistic Evidence for Oxford.” Shakespeare Oxford Newsletter, v. 53, no. 2, pp. 22-25, Spring 2017.

Grosart, Alexander B., ed. “The Poems of Edward de Vere, Earl of Oxford” (1872). In Grosart, ed., Miscellanies of the Fuller Worthies’ Library, n.p. 1876 (in 4 vols.), v. 4 (available in Google Books), pp. 349-51, 359, 394-429.

Hannah, John. The Courtly Poets from Raleigh to Montrose. London: Bell and Daldy, 1870 (available in Google Books).

Hughey, Ruth, ed. The Arundel-Harington Manuscript of Tudor Poetry. Columbus: Ohio State University Press, 1960 (in 2 vols.).

Kreiler, Kurt, ed. & trans. Edward de Vere, Earl of Oxford, One Hundred Poems: Der zarte Faden, den die Schönheit spinn (“The thriftless thread which pamper’d beauty spins”). Germany: Suhrkamp, 2013.

Lee, Sidney. The French Renaissance in England: An Account of the Literary Relations of England and France in the Sixteenth Century. Scribner, 1910 (available in Google Books).

Looney, J. Thomas. “Shakespeare” Identified in Edward de Vere, the Seventeenth Earl of Oxford. London: Cecil Palmer, 1920 (available in the Internet Archive). Reprinted, New York: Stokes, 1920 (available in Google Books). 2d ed., New York: Duell, Sloan & Pearce, 1948. 3d ed. (Ruth Loyd Miller ed.), Port Washington, N.Y.: Kennikat Press, and Jennings, La.: Minos Publishing, 1975 (in 2 vols.), v. 1, pp. 1-470; 4th (“Centenary”) ed., James A. Warren ed. 2018, 1st printing, Forever Press, 2d printing, 2019, Veritas Publications.

_____. The Poems of Edward de Vere, Seventeenth Earl of Oxford. London: Cecil Palmer, 1921. The text is not available in Google Books, but a full pdf is available here (large file) on Mark Andre Alexander’s “Shakespeare Authorship Sourcebook” website. About half the text (pp. i-lxxvii) consists of prefatory essays, with the other half (pp. 1-86) devoted to reprinting the poems viewed by Looney as written (at least possibly) by de Vere. Only the latter half is reprinted in Miller’s 1975 edition of Looney’s 1920 book (v. 1, app. 3, pp. 537-644).

Lyly, John. Collected Works. London: Edward Blount, 1632. Reprinted in The Complete Works of John Lyly (R. Warwick Bond ed.), Oxford University Press, 1902 (in 3 vols.).

May, Steven W. “The Authorship of ‘My Mind to Me a Kingdom Is’.” Review of English Studies, v. 26 (N.S.), no. 104, pp. 385-94, 1975.

_____, “The Poems of Edward de Vere, Seventeenth Earl of Oxford and of Robert Devereux, Second Earl of Essex.” Studies in Philology, v. 77, no. 5, pp. 5-132, 1980.

_____. The Elizabethan Courtier Poets: The Poems and Their Contexts. Missouri University Press, 1991. Reprinted, Pegasus Press (University of North Carolina at Asheville), 1999 (citations to 1991 edition; 1999 reprint appears identical).

_____. “The Seventeenth Earl of Oxford as Poet and Playwright.” Tennessee Law Review, v. 72, no. 1, pp. 221-54, 2004.

Meres, Francis. Francis Meres’s Treatise “Poetrie” (from Palladis Tamia, London: Cuthbert Burby, 1598). Reprinted (Don Cameron Allen ed.), Illinois University Press, 1933 (University of Illinois Studies in Language and Literature, v. 16).

Miller, Ruth Loyd. “The Cornwallis-Lyons Manuscript.” In Looney 1920 (Miller ed. 1975), v. 2 (“Oxfordian Vistas”), ch. 18, pp. 369-94.

_____. “The Earl of Oxford Publishes Hamlet’s Book, ‘Cardanus Comforte’.” In Looney 1920 (Miller ed. 1975), v. 2 (“Oxfordian Vistas”), ch. 24, pt. 3, pp. 496-507.

_____, ed. A Hundreth Sundrie Flowres. London: Richard Smith, 1573 (anonymous). Reprinted as The Posies of George Gascoigne, Esquire, Corrected, Perfected, and Augmented by the Author, London: Richard Smith, 1575. Reprinted as A Hundreth Sundrie Flowres (Bernard M. Ward ed.), London: Etchells & Macdonald, 1926. 2d ed. (Miller ed.), Port Washington, N.Y.: Kennikat Press, and Jennings, La.: Minos Publishing, 1975.

Ogburn, Charlton (Jr.). The Mysterious William Shakespeare: The Myth and the Reality. Dodd, Mead, 1984. Reprinted (2d ed.), McLean, Va.: EPM Publications, 1992 (citations to 1992 edition) (available on Amazon.com).

Oxford English Dictionary (OED). Oxford University Press, 2d ed. 1989 (in 20 vols.).

Peacham, Henry. The Compleat Gentleman. London: Francis Constable, 1622. Reprinted (G.S. Gordon ed.), Oxford University Press, 1906 (available in Google Books).

Prechter, Robert R. “Hundreth Sundrie Flowres Revisited: Was Oxford Really Involved?” Brief Chronicles, v. 2, pp. 43-76, 2010.

_____. “Verse Parallels Between Oxford and Shakespeare.” Oxfordian, v. 14, pp. 148-55, 2012.

Proudfoot, Richard & Nicola Bennett, eds. King Edward III. Bloomsbury Arden Shakespeare, 2017.

Puttenham, George. See Arber, ed., The Arte of English Poesie.

Rollins, Hyder Edward, ed. (see also Edwards, Richard, for full citation). The Paradise of Dainty Devices. London, 1576. Edited by Richard Edwards (1525–66). Reprinted (Rollins ed.), Harvard University Press, 1927.

_____, ed. The Pepys Ballads. Harvard University Press, 1929 (in 2 vols.).

_____, ed. The Poems: A New Variorum Edition of Shakespeare. Lippincott, 1938.

Sams, Eric. Shakespeare’s Edmund Ironside: The Lost Play. Fourth Estate, 1985. Reprinted, Wildwood House, 1986 (citations to 1986 reprint).

Schmidgall, Gary. Walt Whitman: A Gay Life. Dutton, 1997 (available on Amazon.com).

Schoenbaum, Samuel. Shakespeare’s Lives. Oxford UP, 1970, reprinted (rev. ed.), 1991 (citations to 1991 edition).

Shahan, John M. & Richard F. Whalen. “Auditing the Stylometricians: Elliott, Valenza and the Claremont Shakespeare Authorship Clinic.” Oxfordian, v. 11, pp. 235-67, 2009.

Sobran, Joseph. Alias Shakespeare: Solving the Greatest Literary Mystery of All Time. Free Press (Simon & Schuster), 1997 (available on Amazon.com). Sobran discussed Oxford’s early poems primarily in Appendix 2 (pp. 231–70), and his letters primarily in Appendices 3–4 (pp. 271–86). See also Sobran, “Shakespeare Revealed in Oxford’s Early Poetry” (first pub. De Vere Society Newsletter, Jan. 1996, repub. on SOF website, Jan. 22, 2006).

Spevack, Marvin. The Harvard Concordance to Shakespeare. Harvard University Press, 1973.

Stritmatter, Roger A. “The Biblical Origin of Edward De Vere’s Dedicatory Poem in Cardan’s Comforte.” Oxfordian, v. 1, pp. 53-63, 1998.

_____. The Marginalia of Edward de Vere’s Geneva Bible: Providential Discovery, Literary Reasoning, and Historical Consequence. Oxenford Press, 2001 (Ph.D. dissertation, University of Massachusetts, Amherst). Reprinted, 4th ed. 2015 (available on Amazon.com).

Valenza, Robert J. & Ward E.Y. Elliott. See Elliott & Valenza.

Ward, Bernard M., ed., A Hundreth Sundrie Flowres. See Miller ed. 1975.

Warren, James A., ed. An Index to Oxfordian Publications. Somerville, Mass.: Forever Press, 4th ed. 2017 (available on Amazon.com).

Waugh, Alexander, “My Shakespeare Rise!” In William Leahy, ed., My Shakespeare: The Authorship Controversy, Edward Everett Root, 2018, ch. 3, pp. 47-83 (available on Amazon.com).

Webbe, William. A Discourse of English Poetrie. London: John Charlewood for Robert Walley, 1586. Reprinted (Edward Arber ed.), London: Constable, 1895 (available in Google Books).

Whalen, Richard F. & John M. Shahan. See Shahan & Whalen.

Whitman, Walt. “What Lurks Behind Shakspere’s Historical Plays?” In Whitman, November Boughs, Philadelphia: McKay, 1888 (available in Google Books), pp. 52-54.

Whittemore, Hank. 100 Reasons Shake-speare Was the Earl of Oxford. Somerville, Mass.: Forever Press, 2016 (available on Amazon.com).

Return to the Introduction.

[published June 22, 2018, updated 2021]

Membership dues cover only a fraction of our budget, including all our research, preservation and programming. Please support the SOF by making a gift today!

Blue Boar Tavern: Wassail Q&A

Tuesday Dec. 17, 8pm E / 5pm P

Sign up below for event invites!