Twenty Poems of Edward de Vere: Selection of Poems

This section continues the Introduction to the Shakespeare Oxford Fellowship presentation of early poems by Edward de Vere. You may return to the previous section or continue to the next section. The poems themselves (and a printable pdf version of the entire presentation) may be accessed from the Introduction.

Introduction, Part 4: Selection of Poems

This analysis of de Vere’s poetry builds upon and amplifies the pioneering studies published by J. Thomas Looney in 1920 (121-71) and 1921, and by Joseph Sobran in 1997 (231-70), which we gratefully acknowledge. We also supplement and corroborate William Plumer Fowler’s remarkable 1986 book, Shakespeare Revealed in Oxford’s Letters, which followed a similar methodology to reach similar conclusions based on de Vere’s surviving epistolary prose.

See also, e.g., Sobran’s discussion of de Vere’s letters (271-86), Gary Goldstein’s 2016 and 2017 overviews of de Vere’s poetic and epistolary parallels to the Shakespeare canon, Robert Prechter’s 2012 analysis of the parallels to Poem No. 4, the surveys of various poetic parallels by Robert Sean Brazil & Barboura Flues in 2002 and Cheryl Eagan-Donovan in 2017, and Bonner Miller Cutting’s 2017 analysis of de Vere’s letters petitioning for control of a tin monopoly.

Long before Fowler, moreover, Charles Wisner Barrell gathered impressive evidence that “Shakespeare’s thought and imagery dominate Oxford’s own statement of creative principles” (Oct. 1946, 61), a statement set forth in de Vere’s letter prefacing Thomas Bedingfield’s 1573 translation of Girolamo Cardano’s “Cardanus Comforte” — termed “Hamlet’s book” by orthodox scholar Hardin Craig (1934) (see notes to Poem No. 1).

Past editors of de Vere’s poetry have disagreed over the size and variety of his literary corpus. The editions compiled by Hannah (1870), Grosart (1872), Looney (1921), May (1975, 1980, and 1991), Sobran (1997), Chiljan (1998), Brazil & Flues (2002), and Kreiler (2013) (in German), have varied markedly in the number of poems they attribute to him.

Hannah included five poems he attributed to de Vere (142-47), also included No. 18 (though misattributed to Sir Edward Dyer) (149-50), and cited 16 more de Vere poems in notes (without providing their text) (241-42), thus ascribing a total of 21 poems to de Vere. Grosart included 22 poems he attributed to de Vere, and Looney 47, but both Grosart and Looney were unaware that three others (Nos. 12, 13, and 18) might also be credited to him. Chiljan included 26 poems, Brazil & Flues 25, May only 16 (plus four “possibly” by him, for a total of 20 — rejecting or failing to consider many identified by Looney, but including the three that Grosart and Looney omitted), and Sobran 20 (following May’s selection and order).

May has questioned de Vere’s authorship of some poems, such as the “echo” verses (No. 17) apparently written about Oxford’s mistress Anne Vavasour. But May has generally been thoughtful and systematic in approaching the attribution of the poems. In the case of No. 17, May detailed several strong reasons to credit de Vere (1980, 79-80). May deserves particular notice for his fine 1975 article detailing the evidence for de Vere’s authorship of No. 18 (“My Mind To Me a Kingdom Is”), one of the best-loved lyrics in the English language.

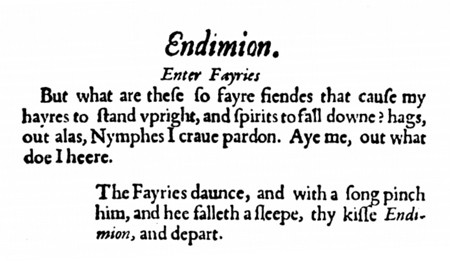

One reason for the larger size of Looney’s edition was that he became the first to suggest that de Vere’s poems include not only those appearing over the initials “E.O.” but also a number of others. The “E.O.” poems were mostly published in The Paradise of Dainty Devices (1576) (see Rollins ed. 1927), or attributed to de Vere in manuscript. Looney included in his edition the lyrics of several songs from John Lyly’s plays, which were omitted from the original quartos and only published in Edward Blount’s 1632 edition of Lyly’s Collected Works. For example, Lyly’s play Endymion (Q1, 1591, G3) merely provides a stage direction that “[t]he Fayries daunce, and with a song pinch him” (see below), while the 1632 edition prints the song.

Looney also claimed for Oxford the otherwise unattributed “Ignoto” poems from England’s Helicon (1600). Kreiler would add many poems originally published in 1573 in A Hundreth Sundrie Flowres (reprinted as the work of Gascoigne in 1575, see Miller ed. 1975; but see Prechter 2010, disputing that Oxfordian attribution; cf. Ogburn 513-19).

These various studies bring the total number of poems possibly attributable to Oxford (leaving aside the Shakespeare canon itself) to as many as a hundred. Thus, while some poems are today canonically established as de Vere’s, many others hang in some form of scholarly doubt or limbo. There is a distinct possibility that more poems and works of prose may ultimately be credited to his pen.

Without prejudicing any of these possible attributions, we choose to focus here (following May and Sobran) on those twenty poems that seem most strongly established as de Vere’s based on direct bibliographical evidence. We believe this conservative selection more than amply illustrates the many and telling links between de Vere’s known verse and Shakespeare’s poetic imagination.

Return to the previous section or continue to the next section. You may also return to the Introduction (with access to all poems).

[published June 22, 2018, updated 2021]

Membership dues cover only a fraction of our budget, including all our research, preservation and programming. Please support the SOF by making a gift today!

Blue Boar Tavern: Wassail Q&A

Tuesday Dec. 17, 8pm E / 5pm P

Sign up below for event invites!