De Vere Poem 1: The Labouring Man That Tills the Fertile Soil

See the Introduction to this presentation of early poems by Edward de Vere. Click here to go to the next poem in the series. All the poems, and a printable pdf version of the entire presentation, may also be accessed from the Introduction. See also Note on Sources, Titles, and Presentation of Parallels, Key to Abbreviations, and Bibliography of Works Cited.

Poem No. 1: “The Labouring Man That Tills the Fertile Soil”

1 The labouring man that tills the fertile soil

2 And reaps the harvest fruit hath not indeed

3 The gain, but pain, and if for all his toil

4 He gets the straw, the Lord will have the seed.

5 The Manchet fine falls not unto his share,

6 On coarsest cheat his hungry stomach feeds.

7 The Landlord doth possess the finest fare;

8 He pulls the flowers, the other plucks but weeds.

9 The mason poor, that builds the Lordly halls,

10 Dwells not in them, they are for high degree;

11 His Cottage is compact in paper walls,

12 And not with brick or stone as others be.

13 The idle Drone that labours not at all

14 Sucks up the sweet of honey from the Bee.

15 Who worketh most, to their share least doth fall;

16 With due desert reward will never be.

17 The swiftest Hare unto the Mastiff slow

18 Oft times doth fall to him as for a prey;

19 The Greyhound thereby doth miss his game we know

20 For which he made such speedy haste away.

21 So he that takes the pain to pen the book

22 Reaps not the gifts of goodly golden Muse,

23 But those gain that who on the work shall look,

24 And from the sour the sweet by skill doth choose.

25 For he that beats the bush the bird not gets,

26 But who sits still, and holdeth fast the nets.

Textual sources: Published as part of the preface to Cardanus Comfort (1573). The dedication to de Vere by the book’s translator, Thomas Bedingfield, is dated January 1, 1571 (1572, modern style). Thus, No. 1 was most likely written c. 1572. See Hannah (145-46); Grosart (422-23); Looney (1921, 14-15, Miller ed. 1975, 1: 572-73); May (#1) (1980, 25, 67, 118; 1991, 270-71).

Structure: Six four-line stanzas rhyming ABAB with terminal couplet.

Looney’s title: “Labour and Its Reward”

Past commentaries on parallels: Sobran (232-34); Brazil & Flues.

Clarifications of the text:

(5-6) The words manchet and cheat refer respectively to wheat bread of premium and second-rate quality (OED 3: 66; 9: 297).

(22) The nine Muses, in Greek mythology, are the inspirational goddesses of poets and other writers, artists, and scholars.

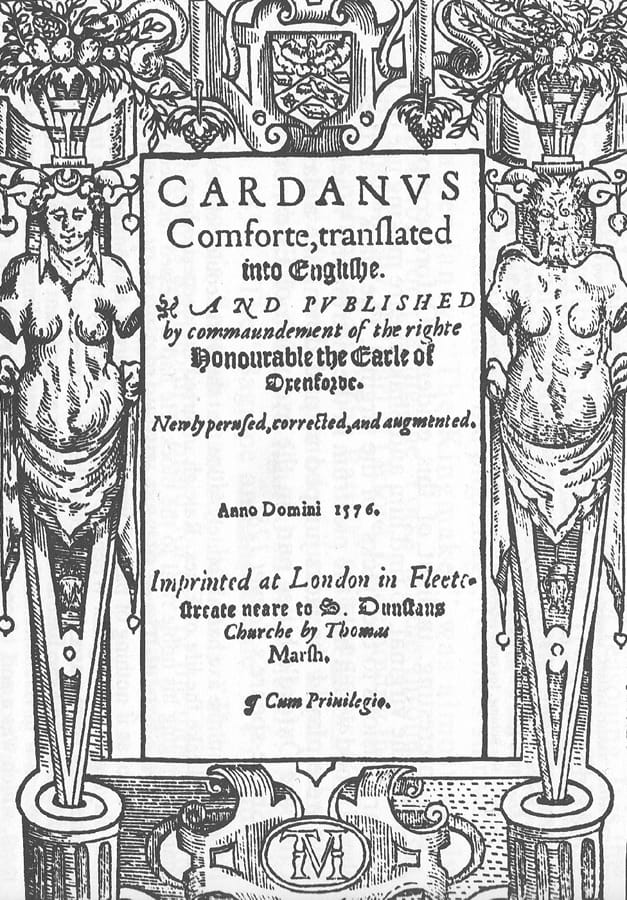

As noted above, No. 1 was published as part of the preface to Bedingfield’s translation of Cardanus Comforte (1573, rev. 1576). It was introduced by the notation “The Earle of Oxenforde to the Reader.” The book was dedicated to the Earl (Edward de Vere), and, as indicated on the cover page below, “published by [his] commandment.”

Cardanus is a philosophical work by the Italian mathematician Girolamo Cardano (1501–76), originally published in Venice as De Consolatione (1542). Its influence on the philosophical dimensions of Hamlet has been widely acknowledged. As discussed by Miller (1975, “Cardanus”), Ogburn (525-28), Sobran (279-86), Stritmatter (1998), and others, orthodox scholars including Hardin Craig have long documented an intimate connection between Cardanus and Hamlet. In a 1934 article (which avoided even mentioning de Vere), Craig termed it “Hamlet’s Book,” believing it to be the one from which the prince reads in act 2, scene 2.

De Vere’s separate prose letter to Bedingfield, directly preceding the poem in the Cardanus preface, was reprinted in full by Grosart (424-26), who praised the letter as “extremely interesting and characteristic, graceful and gracious” (423-24). Looney also reprinted the letter in full (1921, 16-20), which is very much worth the few minutes it takes to read (see pdf here).

Oxfordian scholars have long documented the powerful Shakespearean connections (literary, philosophical, and linguistic) with de Vere’s Cardanus letter — at least since Barrell’s two 1946 articles, the first of which noted that Cardanus itself had by then “long been recognized … as the source from which the author of Hamlet drew inspiration for memorable scenes and striking passages” (35). See also, e.g., Fowler (118-62); Looney (1921, Miller ed. 1975, 1: 574-79).

As Sobran noted (279), de Vere’s Cardanus letter “unmistakably prefigures the Southampton poems of Shakespeare: the Sonnets, Venus and Adonis, and The Rape of Lucrece.” Sobran observed that “the letter anticipates those poems in spirit, theme, image, and other details … borrow[ing], for figurative use, the languages of law, commerce, horticulture, and medicine,” and that it “speaks of publication as a duty and of literary works as tombs and monuments to their authors.” Sobran also noted that the letter has echoes in the Shakespeare plays, including striking parallels to Coriolanus (279-82).

As detailed below, de Vere’s prefatory poem also has significant parallels to the plays.

Strongest parallels to No. 1:

(9-10, 13-14) The mason poor that builds the Lordly halls,

Dwells not in them …

…

The idle Drone that labours not at all

Sucks up the sweet of honey from the Bee

‘For so work the honey-bees … The singing masons building roofs of gold … the lazy yawning drone’ (Hen. V, 1.2.187, 198, 204); ‘Not to eat honey like a drone from others’ labors’ (Per., 2.prol.18-19); ‘Where the bee sucks’ (Tem., 5.1.88); ‘Drones suck not eagles’ blood, but rob beehives’ (2 Hen. VI, 4.1.109); ‘Death, that hath sucked the honey of thy breath’ (R&J, 5.3.92); ‘That sucked the honey of his music vows’ (Ham., 3.1.156); cf. ‘My honey lost, and I, a drone-like bee … In thy weak hive a wand’ring wasp hath crept And sucked the honey which thy chaste bee kept’ (Lucrece, 836, 839-40).

The idea of drones sucking honey from the bees is a characteristic idiom of both samples. See also No. 2.7-8 (The Drone more honey sucks, that laboureth not at all, Than doth the Bee).

(17-20) The swiftest Hare unto the Mastiff slow

…

The Greyhound thereby doth miss his game we know

For which he made such speedy haste

‘like a brace of greyhounds, Having the fearful flying hare in sight’ (3 Hen. VI, 2.5.130); ‘like greyhounds in the slips … The game’s afoot!’ (Hen. V, 3.1.31); ‘thy greyhounds are as swift’ (Shrew, ind.2.47).

The seemingly spontaneous references to the greyhounds (or mastiff) and the hares suggest personal experience of such aristocratic hunting sports.

Additional parallels to No. 1:

(1) The labouring man that tills the fertile soil

‘let the magistrates be labouring men’ (2 Hen. VI, 4.2.18); ‘fertile England’s soil’ (2 Hen. VI, 1.1.238); ‘soil’s fertility’ (Rich. II, 3.4.39).

(2-3) reaps the harvest fruit … for all his toil

‘Scarce show a harvest of their heavy toil’ (LLL, 4.3.323); cf. ‘never ear so barren a land for fear it yield me so bad a harvest’ (Venus, ded.); ‘the main harvest reaps’ (As You, 3.5.103); ‘They that reap must sheaf and bind’ (As You, 3.2.102 ); ‘And reap the harvest which that rascal sowed’ (2 Hen. VI, 3.1.381); ‘We are to reap the harvest of his son’ (3 Hen. VI, 2.2.116); ‘To reap the harvest of perpetual peace’ (3 Hen. VI, 5.2.15); ‘My poor lips, which should that harvest reap’ (Sonnets, 128.7).

(8) He pulls the flowers, the other plucks but weeds

‘They bid thee crop a weed, thou pluck’st a flower’ (Venus, 946); ‘which I have sworn to weed and pluck away’ (Rich. II, 2.3.167); ‘He weeds the corn, and still lets grow the weeding’ (LLL, 1.1.96).

(10) high degree

‘Thou wast installed in that high degree’ (1 Hen. VI, 4.1.17); cf. ‘And thou art but of low degree’ (Oth., 2.3.94); ‘Take but degree away, untune that string, And hark what discord follows’ (Troil., 1.3.109).

(20) speedy haste

‘Good lords, make all the speedy haste you may’ (Rich. III, 3.1.60).

(24) the sour the sweet

‘The sweets we wish for turn to loathed sours’ (Lucrece, 867); ‘Things sweet to taste prove in digestion sour’ (Rich. II, 1.3.236); ‘Speak sweetly, man, although thy looks be sour’ (Rich. II, 3.2.193); ‘How sour sweet music is When time is broke’ (Rich. II, 5.5.42-43); ‘Sweetest nut hath sourest rind’ (As You, 3.2.109); ‘Touch you the sourest points with sweetest terms’ (A&C, 2.2.24); ‘have their palates both for sweet and sour’ (Oth., 4.3.94); ‘To that sweet thief which sourly robs from me’ (Sonnets, 35.14); ‘that thy sour leisure gave sweet leave’ (Sonnets, 39.10); ‘For sweetest things turn sourest by their deeds’ (Sonnets, 94.13).

This sweet/sour antithesis, while undoubtedly commonplace, is the first of many such locutions found in both the de Vere poetry and Shakespeare. Both samples exhibit a marked fondness for antithesis and paradox.

(25-26) For he that beats the bush the bird not gets, But who sits still, and holdeth fast the nets

‘Poor bird, thou’dst never fear the net nor lime’ (Mac., 4.2.34); ‘Look how a bird lies tangled in a net’ (Venus, 67); ‘Birds never limed no secret bushes fear’ (Lucrece, 88).

See also No. 2.5-6 (And he that beats the bush, the wished bird not gets, But such I see as sitteth still, and holds the fowling nets).

Continue to Poem No. 2 or return to the Introduction.

[published June 22, 2018, updated 2021]

Membership dues cover only a fraction of our budget, including all our research, preservation and programming. Please support the SOF by making a gift today!

Blue Boar Tavern: Wassail Q&A

Tuesday Dec. 17, 8pm E / 5pm P

Sign up below for event invites!