The First Folio

of 1623

Called "the book that gave us Shakespeare," the Folio's oddities also produced the Shakespeare Authorship Question.

The First Folio: A Shakespearean Enigma

Shakespeare's First Folio

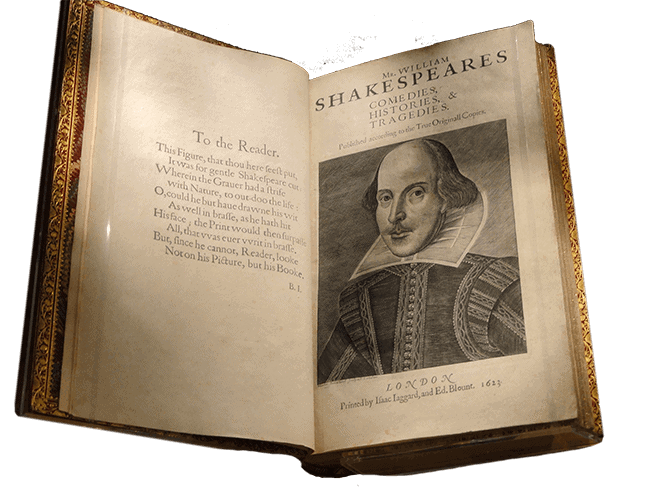

In 2023 we celebrated the 400th anniversary of Shakespeare’s First Folio. This massive book, with more than 900 pages, was first published on November 8, 1623, and was the first collection of the plays of Shakespeare. It contained 18 plays that had never before been published and might otherwise be lost to us today.

The First Folio is a strange work, with significant omissions and contradictions that cast doubt on the authorship of the Shakespeare canon. The production of this great book is also shrouded in mystery and myth. Read on to learn how the First Folio provokes its readers to question the identity of Shakespeare.

Ambiguity in the First Folio

The Folio is claimed as evidence that the man from Stratford was Shakespeare. After all, his name is on the title page! A closer look reveals just how weak the case is. Instead, the book seems designed to inspire doubt about the identity of its writer.

No Shakespeare Biography

The First Folio lacks clear identification of its author. There’s no biography or even biographical information, like date of birth or death. It’s missing the coat of arms that Will and his father worked so hard to attain. In fact, the only association to Will Shakspere is two words on different pages: “Avon” and “Stratford.”

“Stratford” and “Avon”

Surely that clinches it? Well, turns out there are numerous Avon rivers in England — indeed, “avon” means “river.” More intriguingly, Avon is the old name for Hampton Court, a palace on the river Thames where Queen Elizabeth I hosted court theatricals. This gives new meaning to Ben Jonson’s poem where the word makes its appearance:

Sweet Swan of Avon! What a sight it were

To see thee in our waters yet appeare,

And make those flights upon the banks of Thames

That so did take Eliza, and our James!

The “Stratford” reference has a similarly complicated meaning.

Honest Ben Jonson

In the 400 years since the Folio was published, playwright Ben Jonson has been found to have had a far greater involvement in its creation than previously understood. “Honest Ben” had a reputation for ambiguity and literary misdirection, and his fingerprints are all over the introductory pages of the Folio. Most serious scholars today accept that he wrote the prefaces signed by actors John Heminges and Henry Condell.

A Portrait of Shakespeare?

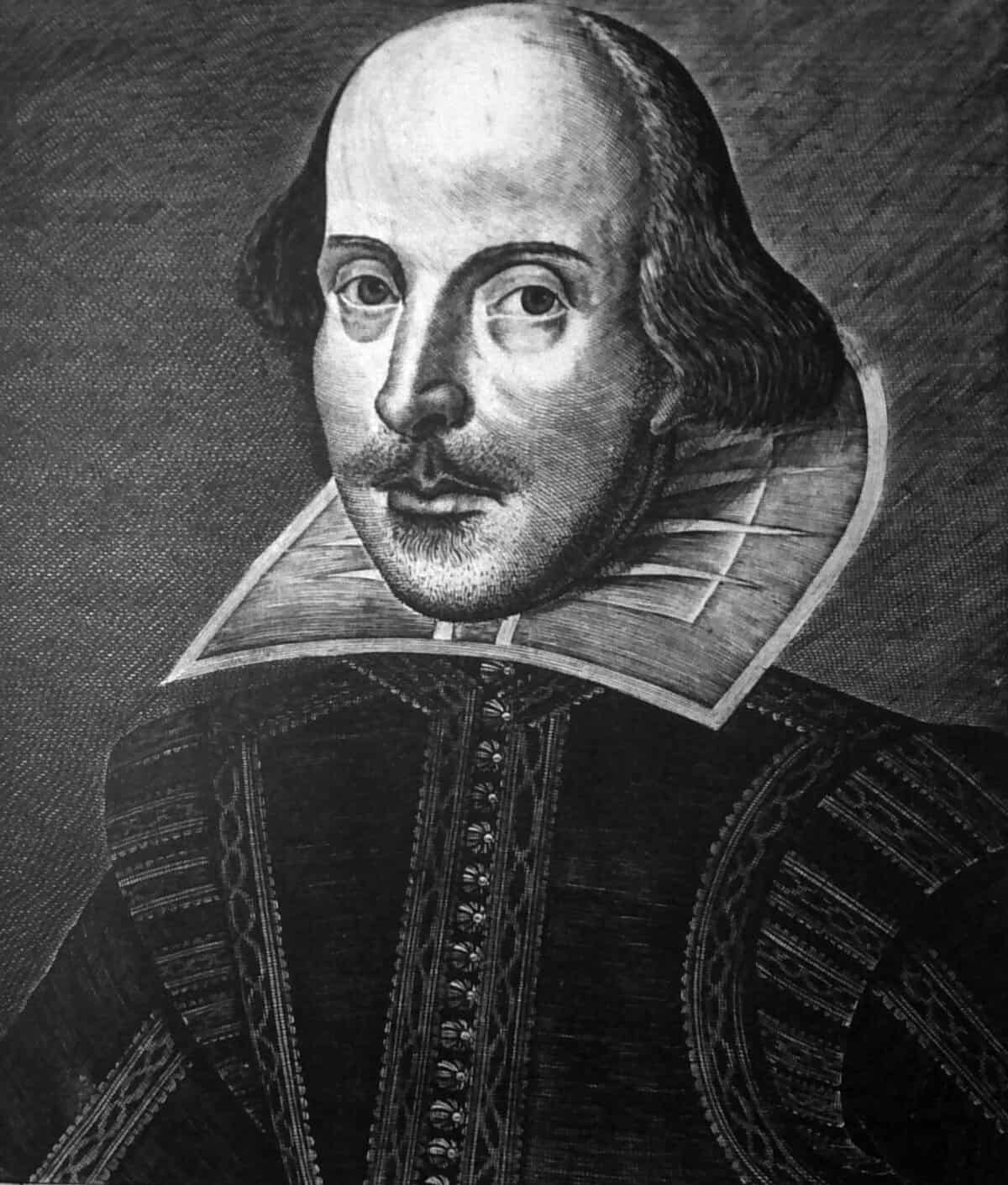

Along with 36 plays, the First Folio provided an image of the author. This engraving, attributed to Martin Droeshout, has been the subject of speculation for centuries for its numerous oddities.

What’s wrong with this picture? Let us count the ways.

Look Not on His Picture

Ben Jonson, in his opening Folio poem, introduces the image by telling the reader “look not on his picture, but his book.” This odd statement offers a hint to separate the art from the image, and when one does look on his picture, things get strange indeed.

Shakespeare scholars and readers through the centuries have unleashed ripe critiques of this picture. “I never saw a stupider face” remarked portrait painter Thomas Gainsborough. Victorian Shakespeare scholars deemed it grotesque, even monstrous. But it wasn’t just the unlifelike qualities that drew attention.

A Mask for an Actor

Scrutiny of the image reveals numerous oddities.

- There’s no ornamentation, in contrast to other author portraits of the day which bear mottoes and classical elements like laurel leaves and columns (see examples below)

- Two left arms? No right = “write” arm?

- Multiple light sources

- Misaligned hair, eyes, nose, mouth

- The line of a mask?

Hover over the image to see some of its peculiarities. Why did engraver Martin Droeshout produce such an austere and awkward representation? Why use such a poorly done portrait in this important and expensive book?

Oversized, bulging cranium. Squint and you can really see this.

Asymmetrical hair poufs. Eye level here, but down at earlobe level on the other side.

Bill forgot to shave on portrait day

Two left arms? Tailors have pointed out that the straight trim on this side belongs on the garment back (compare with curved trim around other shoulder). A coded message that the right arm/writing arm belonged to someone else?

Thick line from ear under chin is suggestive of a mask

Portrait of an Author

The First Folio portrait is missing all the visual tributes accorded to writers of the era: laudatory Latin, sculptural ornamentation, and laurel leaves signifying poetic victory. Compare these typical author images with the stark, unadorned picture above.

Who Really Published the First Folio?

The production of the First Folio is usually attributed to actors John Heminges and Henry Condell. How these busy theater men did the work of editing its nearly 1,000 pages or financed such a luxurious production in an age when most people didn’t own a single book, is generally glossed over. But the true story of the Folio — the political intrigue of its timing and the covert involvement of the true author’s family — sheds a fascinating light on the era and the book.

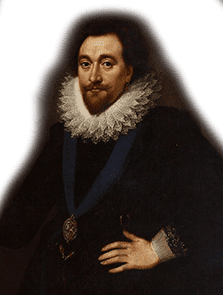

Incomparable Pair

The First Folio is dedicated to William and Philip Herbert, Earls of Pembroke and Montgomery. These wealthy and powerful brothers, called in the Folio dedication the “incomparable pair,” almost certainly provided the funding for the Folio project. Phillip Herbert was married to Susan Vere, daughter of Edward de Vere, 17th Earl of Oxford. The First Folio was a family affair, arranged by the real Shakespeare’s heirs for a beloved elder who was, as Ben Jonson said, “not for an age, but for all time.”

My Name Be Buried

Why this elaborate literary deception? Almost 20 years after his death, why would his family not credit Edward de Vere with the plays?

1623: A National Crisis

The 1623 Shakespeare First Folio was born in a moment of national crisis over James I’s plan to marry his son Charles to the heir to the Catholic Hapsburgs.

During the approximately 20 months of printing of the Folio (c. March 22-November 23), Henry de Vere, the 18th Earl of Oxford, son of Edward, was in the Tower of London for speaking against the match. William and Philip Herbert, used the Folio as a way to advocate for their imprisoned brother-in-law.

Orthodox Shakespeare scholars reduce as much as possible both Jonson’s role in the Folio and its connections to these international events and social networks created through marriages. Restoring this history to the Folio allows us to witness “literary politics” on the ground during the crisis.

Frequently Asked Questions

What is the First Folio?

The first folio is a collection of 36 plays by William Shakespeare, the first collected edition of his plays.

Why is the First Folio significant?

Twenty of the included plays had never before been printed, including The Tempest, Julius Caesar, and Macbeth. The English language is filled with words and phrases coined by Shakespeare.

Doesn’t the First Folio prove that the plays are written by William Shakspere (1564-1616) of Stratford?

No. While the traditional biography of Shakespeare depends on taking the Folio literally and at face value, the book itself does not support such an interpretation, but rather invites attention to its own oddities of construction to raise doubts about the origins of the plays. Ben Jonson’s epigram to the Droeshout engraving, according to orthodox scholar Leah Marcus, “set’s reader’s off on a treasure hunt for the author. Where is the ‘real’ Shakespeare to be found?”

Learn More

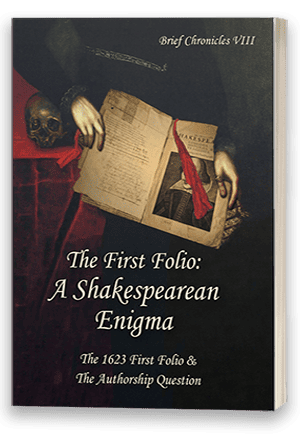

The First Folio: A Shakespearean Enigma

The 1623 First Folio and The Authorship Question

Roger Stritmatter, Editor

To Henry James "the divine William . . . is the biggest and most successful fraud ever practiced on a patient world."

Sampling the research of thirteen First Folio scholars, the book shows how the Folio is designed both to obfuscate and reveal the Shakespeare fraud:

- The oversized “Droeshout” portrait on the title page presents a bizarre image that Professor Northrop Frye says makes Shakespeare “look like an idiot.”

- “The Droeshout’s deficiencies are, alas, only too gross” admits Professor Samuel Schoenbaum.

- Ben Jonson’s poem describes Droeshout’s image as a picture “cut” not “of,” but “for” the “gentle Shakespeare.”

- “The most common meaning of “gentle” in 1623 was “noble.”

- Jonson’s poem also tells the reader to “look not on [Shakespeare’s] picture, but his book.”

- Many readers detect in the arrangement of text and image on the book’s first spread a droll joke about the authorship of the plays.

The nineteen scholarly essays and reviews by 11 contributors cover aspects of the Folio as diverse as bibliographical history, literary analysis, reception studies, and the Folio and the Spanish Marriage crisis. Two contributors (Waugh, “Sweet Swan,” and Stritmatter, “Small Latin”) conduct detailed and exhaustive examination of two key interpretative cruxes in Jonson’s 80-Line “To the Memory of my beloved, The AUTHOR, Mr. William Shakespeare.”