by Alexander Waugh

This article was originally published in The Oxfordian, v. 16, pp. 97–103 (2014) (PDF available here), republished here on the SOF website, Jan. 19, 2017.

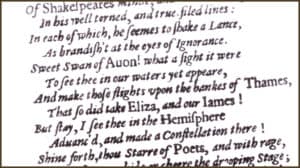

The most celebrated description of “William Shakespeare” occurs in the 71st line of Ben Jonson’s poem “To the memory of My Beloved, The AUTHOR Mr William Shakespeare And what he hath left us,” prefixed to the First Folio of 1623:

Sweet Swan of Avon! What a sight it were

To see thee in our waters yet appeare,

And make those flights upon the banks of Thames

That so did take Eliza, and our James!

“Sweet Swan of Avon” here stands as perhaps the only noticeable light in the flickering Stratfordian firmament, for it is in this seemingly innocuous and posthumous literary record that the poet “William Shakespeare” is identified, for the first time in history, as the actor-manager-businessman, William Shakspere of Stratford-upon-Avon.

“Sweet Swan of Avon” here stands as perhaps the only noticeable light in the flickering Stratfordian firmament, for it is in this seemingly innocuous and posthumous literary record that the poet “William Shakespeare” is identified, for the first time in history, as the actor-manager-businessman, William Shakspere of Stratford-upon-Avon.

It is, of course, only a poetic allusion, and poetic allusions do not carry the same evidentiary weight as prose statements such as, “William Shakespeare was a poet and playwright who came from Stratford-upon-Avon.” “Sweet Swan of Avon” is nevertheless a reference that indisputably points in that direction. Shakespeare’s verse was, after all, described as “sweet,” “sugared,” “mellifluous,” or “honeyed” (cf. Weever, Barnfield, Meres, Heywood, etc.); the “swan” since Virgil’s day was conventionally used as a symbol to represent a poet; and “Avon” is the name of the river that runs through Stratford in Warwickshire where William Shakspere was born in 1564 and died in 1616.

So in “Sweet Swan of Avon” the poet and the actor-money-lender appear, for the first time, united as one. For those who have studied the Shakespeare Authorship Question in sufficient depth to understand why the man from Stratford could not have been the author of the plays and poems traditionally attributed to him, this reference presents something of a rare problem. If the playwright “William Shakespeare” was not from Stratford, why did Jonson describe him as “Swan of Avon”?

Anti-Stratfordians usually try to shrug the problem off with mumblings about “avon” meaning “river” in Welsh and there being at least seven of them in the United Kingdom. This is not a very strong argument. Nor is it persuasive to protest, as some do, that Mary Herbert (née Sydney), Countess of Pembroke, the poetess and Shakespeare authorship candidate, must have been Jonson’s “Sweet Swan” because “Sydney” resembles the French cygnet, a swan. It is sometimes added that she was once pictured wearing a swan pattern on her ruff and that she was buried at Salisbury, a city on the Wiltshire Avon. Against that, she lived all her married life at Wilton, which is on the Wylie.

Oxfordians also occasionally point out that one of Edward de Vere’s properties, the manor of Bilton, near Rugby in Warwickshire, is “on the Avon.” This however must also be discounted as it is situated at least 3.5 kilometers from the river, nor is there any record of Lord Oxford ever having lived there. In fact he leased it to Lord Darcy in 1574 and sold it to John Shuckburgh in 1580, some 43 years before Jonson’s allusion and 24 years before his own death.

While these interpretations are undoubtedly wrong, the wary reader of Jonson’s slippery poem, “To the Memorie of my Beloved THE AUTHOR,” has every reason to suspect a double meaning. It begins with a stark warning against the “silliest ignorance” of those who may believe that they are perceiving truths in his lines, though they are in actual fact only echoes.1 Jonson was a master of poetic ambiguity, and when, as in this exceptional case, he writes a 16-line preface to a poem warning his readers to pay particular attention not to misinterpret his true meaning through “silliest Ignorance,” “blinde Affection” or “crafty Malice,” we would do well to take him at his word. In calling “Shakespeare” a “Sweet Swan of Avon”, Jonson was allowing, and probably expecting, some of his readers—those of “silliest ignorance”—to think of Stratford-upon-Avon, home to the late Mr Will. Shakspere.

But how did he expect the cognoscenti to interpret the phrase? To answer this we need, first, to examine his “Swan of Avon” in context. Jonson reveals that “Shakespeare”, the “Sweet Swan of Avon”, made “flights” on the banks of the Thames greatly pleasing to Queen Elizabeth and her successor, King James.

There can be no doubt that by “flights on the Thames” Jonson meant stage performances of Shakespeare’s plays. I do not know of anyone who disputes this interpretation, though where exactly did the monarchs so enjoy these poetic “flights”? Neither ever attended a public theatre,2 so the Globe, Hope, Rose, and Swan, all situated on the Thames, must be ruled out. Many of Shakespeare’s finest and most sophisticated dramas were written to be performed for the Royal Court and not, “for the gawkish groundlings of the Globe” as Richard Levin and others have pointed out. 3

By far the grandest, most elaborate and most frequently used Court theatre, throughout the reigns of Queen Elizabeth and King James, was the Great Hall at Hampton Court, located in Surrey on the banks of the Thames, 16 miles west of London. It was here that Henry VIII presented masques and other spectacular entertainments to courtiers and visiting dignitaries, and here also that Queen Elizabeth herself acted, where she went often “for her private recreation,”4 and where she mounted huge shrove, summer and Christmas-tide festivals of plays annually from 1572.

When James I came to the throne in 1603 he chose Hampton Court over all his Royal Palaces as the best venue for dramatic entertainment.5 The Revels Accounts reveal that no expense was spared in the construction of stage-sets there. The bill, on one occasion, included charges for the “painting of seven cities, one village, and one country house” and for the importation of trees into the hall intended to represent a wilderness. It is known that the players used the pantry behind the permanent screen at one end of the Hall as a dressing room, and that they rehearsed in the Great Watching Chamber next door.6 King James visited Hampton Court five times in the first half-year of his reign and had no fewer than 30 plays presented there over the 1603-4 Christmastide season including, it is argued, several by Shakespeare.7

Since “William Shakespeare” was the finest playwright of his age, whose works were evidently performed (many presumably for the first time) before Queen Elizabeth and King James upon the grandest courtly stage in England, situated on the banks of the Thames at Hampton Court, it would have been entirely appropriate for Ben Jonson to have alluded to his “beloved, The AUTHOR” as the “Sweet Swan of Hampton Court.”

But he didn’t, so what has all this to do with “Sweet Swan of Avon”? To find the answer we need to look no further than Jonson’s close friend, mentor and erstwhile tutor, William Camden. Jonson described his relation with this great historian as “a pupil once—a friend for ever”, and famously praised him in an epigram:

CAMDEN! Most reverend head, to whom I owe

All that I am in arts, all that I know.

In 1607 Camden published an exhaustive Latin history of Great Britain and Ireland entitled Britannia, with the intention of restoring “antiquity to Britaine and Britaine to its antiquity.” In a chapter entitled “Trinobantes,” he quotes six lines by the historian John Leland, apropos of Hampton Court:

Est locus insolito rerum splendore superbus, Alluiturque vaga Tamisini fluminis unda, Nomine ab antiquo iam tempore dictus Avona. Hic Rex Henricus taleis Octavius aedes Erexit, qualeis tot Sol aureus orbe Non vidit.

The key words here are “dictus Avona.” Jonson, an accomplished Latinist, would have known exactly what they meant. Others may have had to wait for Camden’s 1610 English translation of Britannia, in which (p. 420) Leland’s lines on Hampton Court are rendered thus:

A Stately place for rare and glorious shew There is, which Tamis with wandring stream doth dowse; Times past, by name of Avon men it knew: Heere Henrie, the Eighth of that name, built an house So sumptuous, as that on such an one (Seeke through the world) the bright Sunne never shone.8

So it would appear that Hampton Court was anciently known as “Avon”. Camden’s source was Leland’s Genethliacon of 1543, but this was by no means his only reference to the Royal palace as “Avon.” In his Cygnea Cantio (1545) Leland explained that Hampton Court was called “Avon” as a shortening of the Celtic-Roman name “Avondunum” meaning a fortified place (dunum) by a river (avon), which “the common people by corruption called Hampton.”9 This etymology was supported by Raphael Hollinshed, who wrote in his Chronicles (1586) that “we now pronounce Hampton for Avondune.”10

Edward de Vere’s tutor, the antiquarian Laurence Nowell, also knew of this connection because he transcribed, by hand, the complete “Syllabus” from Leland’s Genethliacon, which contains the entry: “Avondunum. Aglice Hamptoncourte.”11 Historian William Lambarde, in his Topographical and Historical Dictionary of England, written in the 1590s, includes an entry for Hampton Court which, he writes, is “corruptly called Hampton for Avondun or Avon, an usual Name for many Waters within Ingland.”12

Henry Peacham, in his Minerva Britannia (1612) alludes to Hampton Court, which was famously constructed around five noble court-yards, as “AVON courtes.”13 Jonson was a voracious reader,

his Learning such, no Author old or new,

Escapt his reading that deserv’d his view.14

We may be certain then that he knew the work of the famous Leland, both the Genethliacon of 1543 and the famous poem, Swan Song (1545), in which the poet (assuming the guise of a swan) swims down the Thames from Oxford to Greenwich describing the topography of its banks and calling Hampton Court “Avona” no fewer than five times along the way.15

In the unlikely event that the supremely well-read Jonson was unaware of the allusions to “Avon” in Leland, Hollinshed, Lambarde, Nowell and Peacham we must assume, at very least, that he had read his mentor’s and close friend’s greatest work, Britannia, and noticed the reference there. Anti-Stratfordian, John Weever, certainly spotted it because he copied both Leland’s Latin poem and Camden’s translation verbatim into his account of Hampton Court in Antient Funeral Monuments (1631).16 It would appear then, from all these contemporary references, that the name “Avon,” meaning Hampton Court, was a commonly known fact among the educated men and women of Jonson’s day.17

If Jonson correctly predicted that those of “silliest ignorance” among his readers might perceive the mere echo “Avon” as a reference to Stratford Shakspere’s birthplace, he would equally have expected his sharper and more learned readers to appreciate the true meaning of his lines, which is summarized in the following paraphrase: “Sweet Poet, star of the Hampton Court stage What a joy it would be to see your plays, Which so delighted Queen Elizabeth and King James, Performed once again in that Great Hall on the banks of the Thames.”

Adding this to what is already known about Jonson and the First Folio—his repudiation of the Droeshout portrait;18 his satiric penning of the “Heminge-Condell” letters;19 his discrepant accounts of Shakespeare here and elsewhere20—helps to highlight the game he was playing. He was commissioned, we may safely assume, to edit the First Folio without revealing the true identity of its author. While avoiding the outright lie, he carefully laid plausibly deniable false trails, thereby sending those “of silliest ignorance” in one direction, while allowing the enlightened to perceive the truth behind his lines and applaud the ingenuity of his wit. That the cult of Stratfordianism was spawned from these games is regrettable, but for Jonson, at the time, it was a reasonable solution to a difficult and inconvenient problem.21

Jonson, not once but twice in the First Folio, referred to Shakespeare as “gentle.” This word, which derives from the Old French “gentil”, meaning high-born or noble, is defined in the Oxford English Dictionary as “well-born, belonging to a family of position; originally used synonymously with noble.” So if the “sweet swan of Avon/Hampton Court” is a well-born or noble “courtly maker” who could he be? Oxfordians do not need reminding of William Webbe’s commendation of the

noble Lords and Gentlemen in Her Majesty’s Court, which, in the rare devices of poetry, have been and yet are most skilful; among whom the right honourable Earl of Oxford may challenge to himself the title of most excellent among the rest

or of George Puttenham’s statement in The Arte of English Poesie (1589) that

in Her Majesty’s time…have sprung up another crew of Courtly makers, Noblemen and Gentlemen of Her Majesty’s own servants, who have written excellently well as it would appear if their doings could be found out and made public with the rest, of which number is first that noble gentleman Edward Earl of Oxford.

These references support the view that an enlightened reader of Jonson’s lines would first consider that noble gentleman Edward de Vere as the pseudonymous author of “Shakespeare’s” works on reading Jonson’s prefatory verses. But what of the unenlightened, or so-called “delighted” readers? In 1638 William Davenant published poetical advice to “delighted poets”22 warning them against the Avon as a place of Shakespearean pilgrimage. His poem23 entitled “In Remembrance of Master William Shakespeare” begins:

Beware (delighted Poets!) when you sing

To welcome Nature in the early Spring

Your numerous Feet not tread

The Banks of Avon

and concludes with a neat double pun. “Our Vere” (River)24 has long passed away; the poet to remember in connection with the Warwickshire Avon is not “Shakespeare” but the minor versifier, Fulke Greville, who, as Baron Brooke, lived in Warwick Castle on a promontory jutting out into the Avon River, eight miles from Stratford:25

The piteous River wept it selfe away Long since (Alas!) to such a swift decay; That reach the Map;

and looke If you a River there can spie; And for River your mock’d Eie, Will find a shallow Brooke.26

Alexander Waugh is an English writer, critic and journalist best known for his biography of Paul Wittgenstein, The House of Wittgenstein: A Family at War (2009). He is a signatory of the Declaration of Reasonable Doubt, Honorary President of the Shakespeare Authorship Coalition, and co-editor with John Shahan of Shakespeare Beyond Doubt? (2013). His Amazon-Kindle Short “Shakespeare in Court’” will be published mid-September 2014.

Waugh inherits a distinguished literary tradition, including his grandfather Evelyn and his father Auberon. His biography, Fathers and Sons (2004), portrays five generations of males in his family and was made into a 90minute BBC documentary. Bon Voyage!, written with his brother Nathaniel, won the Vivian Ellis Award for Best New Musical.

This essay was originally titled “The True Meaning of Ben Jonson’s Phrase: ‘Sweet Swan of Avon!’”

Notes

- Jonson writes apropos of praising Shakespeare’s name: “But these ways / were not the paths I meant unto thy praise: for seeliest Ignorance on these may light, / which, when it sounds at best, but ecchos right; / Or blinde Affection, which doth ne’er advance / The truth, but gropes, and urgeth all by chance / Or crafty Malice, might pretend this praise, / And think to ruine, where it seem’d to raise.” The warning against “crafty malice” suggests that Jonson is pointing at those who would raise the name of “Shakspere” to the deliberate detriment of Edward de Vere.

- According to Edmond Malone neither Elizabeth nor James ever attended a public theatre. The first recorded attendance of a British monarch at a public theatre was Queen Henrietta Maria’s visit to the Blackfriars to see Massinger’s now lost Tragedy of Cleander (16 May 1634). See Poems and Plays of Shakespeare, Variorum Edition, (1821), Vol 3, pp. 166-7.

- Richard Levin: “Shakespeare’s Second Globe,” TLS (25 Jan 1974), p. 81.

- “Remembrancia 407”, cited in E. K. Chambers: Elizabethan Stage, (1923), Vol IV, p. 100.

- See E. K. Chambers, The Elizabethan Stage (1923), Vol IV, pp. 77-128 passim.

- Details of theatrical entertainments at Hampton Court drawn from Ernest Law: A Short History of Hampton Court (2nd ed., 1906), pp. 153-4 and 164.

- See E. K. Chambers, The Elizabethan Stage (1923), Vol IV, p. 117.

- Camden’s translation shows that the name “Avon” applies to the place (Hampton Court), not to the river Thames, but English does not afford the same clarity as Latin. In Leland’s original the fact that the place (“locus”) is named Avon (“dictus Avona”) and not the Thames (“Tamisini”) genitive case is unequivocal. In some 18th century translations from Camden (eg. Bishop Gibson, 1722), the name “Avon” is inaccurately changed to “Hampton” possibly in respect for the new Stratfordianism.

- “Avondunum propius nomen exprimit…quam vulgus Hampton corrupte pro Avondune vocat. Sed nos brevitati studemus. Est enim Avon frequens fluviis nomen apud Britannos.” From Kykneion Asma–Cygneia cantio (1545), p. 108. Leland is alluding to the fact that –dunum (in Avondunum) is a CelticRoman suffix meaning a “fortified place”. The original meaning of Avondunum was therefore “fort by the river.”

- Raphael Hollinshed: The First and Second volumes of Chronicles, augmented by John Hooker (1586), p 101.

- See Rebecca Brackmann: The Elizabethan Invention of Anglo-Saxon England: Laurence Nowell, William Lambarde and the Study of Old English (2012), p. 112.

- This quotation is found sub. “Hampton” in Lambarde’s Dictionary, written in the 1590’s but withdrawn due to the threat of competition from Camden’s Britannia, hence unpublished until 1730, but not necessarily unknown to Jonson.

- In Henry Peacham’s “Rura mihi et silentium” from Minerva Britanna (1612), p. 185, the poet muses on what he would be able to do were he free and well-born, envisaging a “solitarie academe” neere “princely RICHMOND” or “AVON courtes.”

- Lucius Carey, Viscount Falkland: “An Eclogue on the Death of Ben Jonson” in Jonsonus Virbius (1638), p. 4.

- For instance, lines 110-1: “Next, moving further down river, I came to the lofty and conspicuous palace of Avona.” Leland’s use of “Avona” as opposed to “Avon” in Swan Song and other Latin verses is purely poetical.

- See A. Waugh: “John Weever – Another Anti-Stratfordian”, DVS Newsletter (May 2014), pp 12-15; Weever’s ref. to Hampton Court as “Avon” may be found in Antient Funeral Monuments (1631), p. 446.

- Acknowledgement of this fact continued into the 18th Century, see for example: The Law-Latin Dictionary (London 1701) by F.O: “Hampton Court. Avona”; Jean Baptiste Bullet: Memoires sur la Langue Celtique (1754), p. 358: “HAMPTONCOURT – Anciennement Avone au bord de la Tamise”; Polwhele’s Historical Views of Devonshire (1793), Vol 1, p. 175: “Hampton Court, now a royal palace of our Soveraign, was first called Avon in that it stood on the river” etc.

- Jonson wrote next to the Droeshout image of Shakespeare: “Reader, Looke not on his picture but his Booke.” Droeshout’s clownish effigy was subsequently ridiculed in the Second Folio (1632), Shakespeare’s Poems (1640) and Brome’s Five New Plays (1653).

- That Jonson was the true author of the “Heminge-Condell” letters in the First Folio was placed beyond doubt by George Steevens in the 18th Century. For his masterly proof see Boswell’s Malone (Third Variorum, 1821), Vol 2, p. 663.

- Jonson’s description of “My Shakespeare…The AUTHOR…Soul of the Age!” in the First Folio (1623) contrasts sharply with his description of the Stratford actor in Discoveries where he writes of Shakspere “(whatsoever he penn’d)” – as a windbag who cannot shut his mouth or learn his lines properly (Discoveries 1l. 646-668). In conversation with William Drummond (if Robert Sibbald’s 18th Century ms transcription is to be trusted) Jonson stated that “Shakspear wanted Arte.”

- That Jonson may have regretted setting up the player, Shakspere, as the false icon of a new cult is suggested in his veiled confession to the fact that in honoring the actor’s memory in the way he did (presumably through the Heminge-Condell letters) he had transgressed “this side idolatry.” The passage, which occurs in the posthumously published Discoveries, is labeled “de Shakespeare nostrat[im]” in Timber or Discoveries (1641).

- For other examples of “delighted” used to mean “unenlightened” or “deprived of light” see Ingilby Centurie of Praise (1888), vol. 1 p. 217.

- William Davenant “In Remembrance of Master William Shakespeare” from Madagascar, with other Poems (1638, imp. 1937), p. 37.

- “Our Vere” is a phrase used by William Covell (1595) and Gervase Markham (1624). Davenant is addressing poets to whom “our Vere” (an apparent pun on R-ver) would suggest Edward de Vere as the poets’ ring-leader.

- “De-lighted” (unenlightened) Stratfordians insist that Leonard Digges in his First Folio tribute refers to the Shakespeare monument at Stratford with the lines “Time dissolves thy Stratford Moniment, Here we alive shall see thee still.” But Digges (like Jonson) uses the Spenserian word “moniment” which is not the same as “monument.” See George Mason’s Supplement to Jonson’s Dictionary (1801), sub “moniment” which defines the word as “a memorial” which might include anything written or set up to preserve the memory of a person or thing. Digges’s reference to “thy Stratford Moniment” might, therefore, have referred to nothing more than Jonson’s ambiguous allusion to “Sweet Swan of Avon” three pages earlier.

- The idea that pilgrims would be “mocked” if they looked for the author “Shakespeare” at Stratford-uponAvon, was wittily enforced by the antiquarian, William Dugdale, who, in 1634, drew a picture of the Shakespeare monument with apes’ faces jeering at the onlooker from each of the capitals on the pillars either side of the sack bearing figure of grain-dealer, William Shakspere.