De Vere Poem 17: Sitting Alone Upon My Thought (Echo Verses)

See the Introduction to this presentation of early poems by Edward de Vere. Click here to go to the next poem or the previous poem in the series. All the poems, and a printable pdf version of the entire presentation, may also be accessed from the Introduction. See also Note on Sources, Titles, and Presentation of Parallels, Key to Abbreviations, and Bibliography of Works Cited.

Poem No. 17: “Sitting Alone Upon My Thought” (Echo Verses)

1 Sitting alone upon my thought, in melancholy mood,

2 In sight of sea, and at my back an ancient hoary wood,

3 I saw a fair young lady come, her secret fears to wail,

4 Clad all in colour of a nun, and covered with a veil.

5 Yet, for the day was clear and calm, I might discern her face,

6 As one might see a damask rose hid under crystal glass.

7 Three times with her soft hand full hard on her left side she knocks,

8 And sighed so sore as might have moved some pity in the rocks.

9 From sighs, and shedding amber tears, into sweet song she brake,

10 When thus the echo answered her to every word she spake.

11 “O heavens, who was the first that bred in me this fever?”

[echo] Vere.

12 “Who was the first that gave the wound, whose scar I wear for ever?”

[echo] Vere.

13 “What tyrant Cupid to my harms usurps the golden quiver?”

[echo] Vere.

14 “What wight first caught this heart, and can from bondage it deliver?”

[echo] Vere.

15 “Yet who doth most adore this wight, O hollow caves, tell true?”

[echo] You.

16 “What nymph deserves his liking best, yet doth in sorrow rue?”

[echo] You.

17 “What makes him not regard good will with some remorse or ruth?”

[echo] Youth.

18 “What makes him show, besides his birth, such pride and such untruth?”

[echo] Youth.

19 “May I his beauty match with love, if he my love will try?”

[echo] Aye.

20 “May I requite his birth with faith? Then faithful will I die?”

[echo] Aye.

21 And I, that knew this lady well,

22 Said Lord, how great a miracle,

23 To hear how echo told the truth,

24 As true as Phoebus’ oracle.

Textual sources: Various manuscripts, including Rawlinson MS 85 (Bodleian Library, Oxford University) (generally followed here), Folger Library MS V.a.89, Harleian MS 7392(2) (British Library), and the Harington MS version published in The Arundel-Harington Manuscript of Tudor Poetry (Ruth Hughey ed. 1960). No. 17 is generally dated c. 1581. See Hannah (241, text not provided); Grosart (411-12); Looney (1921, 2-3, Miller ed. 1975, 1: 560-61); May (PBO #1) (1980, 38-39, 79-81, 121-22; 1991, 282-83).

Structure: Ten lines of rhyming couplets, iambic “fourteeners” defining a scene of action, followed by ten lines of questions rhyming with answers punning on de Vere’s name, with a coda of four lines of iambic tetrameter playing on de Vere’s heraldic motto, Vero Nihil Verius (“Nothing Is Truer Than Truth” — also suggesting “No One Is Truer Than a Vere”).

Looney’s title: “Echo Verses”

Past commentaries on parallels: Looney (1920, 141-45, 162-64; 1921, lxxiii-lxxiv); Ogburn (393); Sobran (260-62); May (2004, 224); Goldstein (2016, 48-49; 2017, 22-23); Whittemore (250-51).

Clarifications of the text:

(11-14) As Looney noted (1920, 162-63), Vere in the echoes to lines 11-14 would be pronounced “Vair.”

(11-20) There are no quotation marks around the fair young lady’s words in the manuscript sources. May added quotation marks but Looney did not. They are used here for clarity. See also comment on line 11 in the manuscript comparison chart below.

(13) Cupid, in classical mythology, is the god of love (see line 19) and desire (see line 11, “fever”).

(14-15) A wight means a person (who can be male or female), with some connotation of commiseration or contempt (OED 20: 328).

(24) Phoebus (see also Nos. 14.31, 19.8, and 20.4) is an epithet for Apollo (see No. 3.6), Greco-Roman god of the sun.

It appears to be generally agreed (see May 1980, 79-80) that No. 17 was inspired by de Vere’s relationship with his mistress Anne Vavasour (c. 1560–c. 1650). Their affair began around 1579, produced a son (Sir Edward Vere) born in March 1581, and apparently ended later that year (see, e.g., Anderson 161-65, 172-73, 178-81).

Professor May (1980, 79-80) acknowledged strong reasons (convincing, we think) to accept de Vere’s authorship of No. 17, though he also questioned the attribution. May’s text of No. 17 relies on the Folger manuscript, which has the name “Vavaser” attached to it. Looney’s text relies on the Rawlinson manuscript, which identifies “the Earl of Oxford” as the author and seems, overall, the preferable version (thus primarily relied upon here). The Harington MS also provides what May describes (1980, 79) as a “convincingly detailed” ascription of No. 17 to Oxford (Sir John Harington was a courtier and contemporary in a position to know).

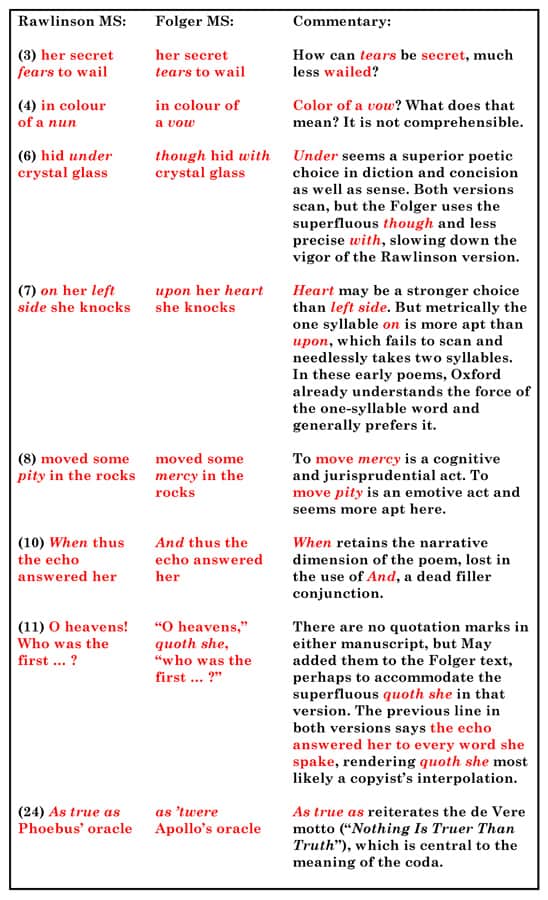

Several passages in No. 17 in the Rawlinson and Folger MSS are compared below (with modernized spelling):

Strongest parallels to No. 17:

(1-4, 9) Sitting alone upon my thought, in melancholy mood,

In sight of sea, and at my back an ancient hoary wood,

I saw a fair young lady come, her secret fears to wail,

Clad all in colour of a nun, and covered with a veil

…

From sighs, and shedding amber tears, into sweet song she brake

Compare the opening lines above to those opening A Lover’s Complaint:

From off a hill whose concave womb re-worded

A plaintful story from a sist’ring vale,

(1-2)

Ere long [I] espied a fickle maid full pale,

Tearing of papers, breaking rings a-twain,

Storming her world with sorrow’s wind and rain.

(5-7)

Upon her head a platted hive of straw,

Which fortified her visage from the sun

(8-9)

Oft did she heave her napkin to her eyne [eyes],

(15)

That seasoned woe had pelleted in tears,

(18)

As often shrieking undistinguished woe

(20)

See also: ‘Sitting on a bank, Weeping again the King my father’s wrack, This music crept by me upon the waters’ (Tem., 1.2.390-92); cf. ‘Sweet Cytherea, sitting by a brook With young Adonis … told him stories to delight his ear’ (Pass. Pilg., 4.1-2, 5); ‘Venus, with young Adonis sitting by her Under a myrtle shade, began to woo him’ (Pass. Pilg., 11.1-2).

The parallels here all involve sitting in evocative wilderness settings where some music or story (or both, i.e., a song) are then heard. More broadly, No. 17, A Lover’s Complaint, and Venus and Adonis — and the above-quoted scene in The Tempest — all unite in presenting a natural setting for solitary anguish and tears.

As Looney stated (1921, lxxiii): “In each case [Oxford’s No. 17 and Shakespeare’s Venus] we have a female represented as pouring out her woes and being answered by echoes from caves; and in both cases the echoing is preceded by three identical conceptions in an identical order. First she beats her heart, next the caves are moved by pity, and then she breaks into song; after which comes the echo.” See parallels below between lines 7-10 & 15 and Venus.

Strikingly, for that male-centric era, in all three poems — No. 17, Complaint, and Venus — we overhear a female soliloquy of romantic woe (seen by a hidden, passive observer of unstated gender in both No. 17 and Complaint). See all three related but distinct sets of parallels below, to lines 7-10 & 15, to line 8 (moved some pity in the rocks) (including another echo in Complaint), and to lines 8-9.

The lamenting lady in Complaint (like Shakespeare’s Venus) seems to be significantly older (“carcass of a beauty spent and done [line 11] … Some beauty peeped through lattice of seared age [line 14]”) than the fair young lady of No. 17. De Vere, likewise, when writing Complaint as “Shakespeare” — a pseudonym first used in print with the publication of Venus when he was 43 — may have been significantly older than when he wrote No. 17 (presumably around the time his affair with Vavasour ended, when he was 31).

(7-10, 15) … full hard on her left side she knocks,

And sighed so sore …

From sighs, and … tears, into sweet song she brake

When thus the echo answered her to every word she spake

…

“O hollow caves, tell true”

Note that the Folger manuscript version of line 7 reads upon her heart she knocks. The heart is on the left side of the chest. Note also that line 19 twice refers explicitly to love, the overall theme.

Now compare, as Looney did (1920, 162-63), the following 13 lines (including two full stanzas) from the first work published as by “Shakespeare” in 1593. That poem, Venus and Adonis (like No. 17), depicts a lovelorn female alone in a wilderness setting (Venus, after Adonis eludes her), who proceeds to lament her woes, sighing and groaning sorely and knocking upon her heart — also breaking into song — while most distinctively of all, caves echo every word she speaks:

And now she beats her heart, whereat it groans,

That all the neighbor caves, as seeming troubled,

Make verbal repetition of her moans.

Passion on passion deeply is redoubled:

‘Ay me!’ she cries, and twenty times, ‘Woe, woe!’

And twenty echoes twenty times cry so.

She, marking them, begins a wailing note

And sings extemporally a woeful ditty —

How love makes young men thrall, and old men dote;

How love is wise in folly, foolish-witty.

Her heavy anthem still concludes in woe,

And still the choir of echoes answer so.

Her song was tedious and outwore the night[.]

(Venus, 829-41)

See also: ‘echo replies’ (Venus, 695); ‘fetch shrill echoes from the hollow earth’ (Shrew, ind.2.44); ‘with heart-sore sighs’ (Two Gent., 1.1.30); ‘With nightly tears and daily heart-sore sighs’ (Two Gent., 2.4.129); cf. ‘every word doth almost tell my name’ (Sonnets, 76.7).

Pursuing the parallels (dare we say echoes?) to lines 10 and 15 in particular, and noting the fair young lady’s repeated questions in lines 11-20 (the echo answering “Vere” in lines 11-14), consider also the following line uttered by yet another Shakespearean female enraptured by the pangs of love, calling out to her beloved (see Looney 1920, 163-64):

‘[Juliet:] Bondage is hoarse and may not speak aloud, Else would I tear the cave where Echo lies And make her airy tongue more hoarse than mine With repetition of “My Romeo”!’ (R&J, 2.2.161-64).

These parallels reveal both de Vere and Shakespeare deploying the same observant (Ovidian?) association between cave and echo.

(8) moved some pity in the rocks

‘O if no harder than a stone thou art, Melt at my tears, and be compassionate; Soft pity enters at an iron gate’ (Lucrece, 593); ‘Pity, you ancient stones, those tender babes’ (Rich. III, 4.1.98); ‘What rocky heart to water will not wear?’ (Lover’s Comp., 291); cf. ‘Beat at thy rocky and wrack-threat’ning heart’ (Lucrece, 590); ‘hard’ned hearts, harder than stones’ (Lucrece, 978).

See also: ‘He is a stone, a very pebble stone, and has no more pity in him than a dog’ (Two Gent., 2.3.11); ‘I am not made of stones, But penetrable to your kind entreats’ (Rich. III, 3.7.224); ‘Your sorrow beats so ardently upon me That it shall make a counter-reflect ’gainst My brother’s heart and warm it to some pity, Though it were made of stone’ (Kins., 1.1.126-29); cf. ‘I would to God my heart were flint, like Edward’s, Or Edward’s soft and pitiful like mine’ (Rich. III, 1.3.140); ‘May move your hearts to pity’ (Rich. III, 1.3.348).

Looney noted “the recurrence of what seems … a curious appeal for pity” (1920, 161) in these de Vere poems and the works of Shakespeare. The word pity (including variants) appears more than 300 times in the Shakespeare canon (Spevack 980-81). In addition to line 8, see also No. 3.7 (the less she pities me), No. 9.36 (pity me), and, e.g.:

‘This you should pity rather than despise’ (Dream, 3.2.235); ‘Pity me then’ (Sonnets, 111.8, 13); ‘Thine eyes I love, and they as pitying me … And suit thy pity like in every part’ (Sonnets, 132.1, 12); ‘my pity-wanting pain’ (Sonnets, 140.4).

Compare also de Vere’s 1572 letter: “on whose tragedies we have an [sic] number of French Aeneases in this city, that tell of their own overthrows with tears falling from their eyes, a piteous thing to hear but a cruel and far more grievous thing we must deem it them to see” (Fowler 55).

The same idea is expressed in different words by Shakespeare: ‘To see sad sights moves more than hear them told, For then the eye interprets to the ear The heavy motion that it doth behold’ (Lucrece, 1324-26).

Additional parallels to No. 17:

(1) melancholy mood

‘moody and dull melancholy’ (Errors, 5.1.79).

(4) Clad all in colour of a nun, and covered with a veil

‘But like a cloistress she will veiled walk’ (Twelfth, 1.1.27); cf. ‘Where beauty’s veil doth cover every blot’ (Sonnets, 95.11).

(5-6) I might discern her face, As one might see a damask rose

‘I have seen roses damasked, red and white, But no such roses see I in her cheeks’ (Sonnets, 130.5-6); cf. ‘[he] calls me e’en now … through a red lattice, and I could discern no part of his face from the window’ (2 Hen. IV, 2.2.74-75); ‘feed on her damask cheek’ (Twelfth, 2.4.112); ‘as sweet as damask roses’ (Win., 4.4.220); ‘With cherry lips and cheeks of damask roses’ (Kins., 4.1.74).

See also No. 14 (lines 21, 23 & 25-27) (damask rose and related parallels) and the discussion in the Introduction (Evaluating the Poetic Parallels).

(7) her soft hand

‘her soft hand’s print’ (Venus, 353); cf. ‘thy soft hands’ (Venus, 633).

(8-9) sighed so sore … sighs, and shedding amber tears

As discussed above, A Lover’s Complaint and The Tempest (especially the former) contain significant parallels to line 9 (sighs … tears), as well as to lines 1-4. More broadly, there are around two dozen Shakespearean references to shedding tears (Spevack 1129-30). See, e.g.:

‘Sighs dry her cheeks, tears make them wet again’ (Venus, 966); ‘My sighs are blown away, my salt tears gone’ (Venus, 1071); ‘Be moved with my tears, my sighs, my groans’ (Lucrece, 588); ‘sighs and groans and tears’ (Lucrece, 1319); ‘With nightly tears and daily heart-sore sighs’ (Two Gent., 2.4.129); ‘upon the altar of her beauty You sacrifice your tears, your sighs, your heart’ (Two Gent., 3.2.72-73); ‘Can you … behold My sighs and tears and will not once relent?’ (1 Hen. VI, 3.1.107-08); ‘Lest with my sighs or tears I blast or drown King Edward’s fruit’ (3 Hen. VI, 4.4.23-24); ‘what ’tis to love. It is to be all made of sighs and tears’ (As You, 5.2.78-79); ‘sighs and tears and groans Show minutes, times, and hours’ (Rich. II, 5.5.57-58).

The foregoing is only a sampling of the many Shakespearean references to sigh(s/ing), etc., in connection with tears, weeping, groaning, etc. (Spevack 1144-45). On tears and sighs, see also No. 9.1-2, and on the broader theme of tears and weeping, Nos. 3.13, 4.10, 5.12, and 6.26.

(11) “bred in me this fever”

‘the raging fire of fever bred’ (Errors, 5.1.75).

(12) “Who was the first that gave the wound, whose scar I wear for ever?”

‘When griping grief the heart doth wound, And doleful dumps the mind oppress’ (R&J, 4.5.126). Both samples use and parody wound as a metaphorical extravagance.

(13) “What tyrant Cupid to my harms usurps the golden quiver?”

‘if Cupid have not spent all his quiver in Venice’ (Much, 1.1.241-42). Shakespeare often uses usurp and its variants figuratively (Spevack 1420), as it is used here in de Vere’s lyric.

(14) “can from bondage it deliver”

‘Cassius from bondage will deliver Cassius’ (Caes., 1.3.90).

(19-20) “May I his beauty match with love … May I requite his birth with faith?”

‘I will requite you with as good a thing’ (Tem., 5.1.169); cf. ‘love on, I will requite thee’ (Much, 3.1.111); ‘I do with an eye of love requite her’ (Much, 5.4.24); ‘if he love me to madness, I shall never requite him’ (Merch., 1.2.59-60); ‘I thank thee for thy love to me, which … I will most kindly requite’ (As You, 1.1.127-28); ‘To make a more requital to your love’ (John, 2.1.34); ‘I will requite your loves’ (Ham., 1.2.251).

(24) As true as Phoebus’ oracle

‘And in Apollo’s name, his oracle’ (Win., 3.2.118); ‘There is no truth at all i’ th’ oracle!’ (Win., 3.2.138); ‘Apollo said, Is’t not the tenor of his oracle’ (Win., 5.1.38).

Phoebus (also referenced in Nos. 14.31, 19.8, and 20.4) is an epithet for Apollo, Greco-Roman god of the sun. There are 23 references to Phoebus (including one spelled “Phibbus”) in canonical Shakespeare (Spevack 976-77). Apollo is referenced once in these de Vere poems (No. 3.6) and 29 times in canonical Shakespeare (Spevack 54).

Continue to Poem No. 18, return to Poem No. 16, or return to the Introduction.

[published June 22, 2018, updated 2021]

Membership dues cover only a fraction of our budget, including all our research, preservation and programming. Please support the SOF by making a gift today!

Blue Boar Tavern: Wassail Q&A

Tuesday Dec. 17, 8pm E / 5pm P

Sign up below for event invites!