The Case for Oxford Revisited

by Ramon Jiménez

In his biography of William Shakespeare, the critic Sir Jonathan Bate wrote: “Gathering what we can from his plays and poems: that is how we will write a biography that is true to him” (xix). This statement acknowledges a widely recognized truth — that a writer’s work reflects his milieu, his experiences, his thoughts, and his own personality. It was the remarkable gap between the known facts about Shakespeare of Stratford-upon-Avon and the traits and characteristics of the author revealed in the Shakespeare canon that led an English schoolmaster to suppose that the real author was someone else, and to search for him in the backwaters of Elizabethan poetry.

This inquiry led him to conclude that “William Shakespeare” was a nom de plume that concealed the identity of England’s greatest poet and dramatist, and that continued to hide it from readers, playgoers, and scholars for hundreds of years. In 1920, J. Thomas Looney published his unique work of investigative scholarship, demonstrating that the man behind the Shakespeare name and the Shakespeare canon was Edward de Vere, the 17th Earl of Oxford (1550–1604).[1]

Since then, hundreds of books and articles have augmented the evidence that this unconventional nobleman and courtier not only wrote the plays and poems attributed to Shakespeare, but concealed the fact of his authorship throughout his life. It appears that after his death his descendants and those in their service deliberately substituted an alternative author and fabricated physical and literary evidence to perpetuate the fable.

The web of evidence associating Oxford with the Shakespeare canon is robust and far-reaching, and grows stronger and more complex every year. Although he was recognized by his contemporaries as an outstanding writer of poetry and plays, he is the only leading dramatist of the time whose name is not associated with a single play. This fact, alone, about any other person would be sufficient to stimulate intense interest and considerable research. Yet the Shakespearean academic community has not only failed to undertake this research itself, it has willfully and consistently refused to allow presentations or to publish research on the Authorship Question by anyone who disputes the Stratford theory. What Oxfordian research it does not ignore, it routinely dismisses, usually with scorn and sarcasm, as unworthy of serious consideration.

However, during the ninety years since Looney’s revelations, the continuing and comprehensive investigation of the biography of the putative author, William Shakespeare of Stratford-upon-Avon, has failed to produce any evidence of his connection to the Shakespeare canon, other than several ambiguous phrases in the prefatory material to the First Folio, published seven years after his death (Price, “Unorthodox,” 190–91). In addition, repeated examinations of the documents of the Elizabethan theater have unearthed nothing that supports the theory of the Stratford man’s authorship, and have revealed that no one who knew him associated him with literature of any kind.[2] On the other hand, Looney’s conclusions, drawn from the plays and poems themselves, about the playwright’s personality, his education, his selection of plots and characters, his familiarity with foreign countries and languages, his attitudes about women, money, public order, and the crown, all comport with what we have learned about Edward de Vere.

Attributes of the Playwright

Walt Whitman was one of the first to doubt the Stratford theory and to suggest that the author was an aristocrat — “one of the ‘wolfish earls’ so plenteous in the plays themselves, or some born descendant and knower” (II, 404). It is a truism that Shakespeare almost always writes from an aristocratic point of view and tends to support the interests and reflect the attitudes of the aristocracy. His heroes and his villains are members of royal families, the nobility, or the wealthy, and all but one of the plays are set in their royal courts or their homes. A great number of the images and metaphors that Shakespeare uses come from the hobbies and diversions of Elizabethan aristocrats and wealthy people: falconry; hunting, especially with dogs; fencing and dueling; archery; horsemanship; bowls; and card games.

Shakespeare reveals not only a precise and comprehensive knowledge of all these activities, but a facile and consistent use of language, imagery, simile and metaphor based upon them (Spurgeon 26–27, 30–32, 110–11). There is little argument that the canon reflects these characteristics. The historian Hugh Trevor-Roper described Shakespeare as a “cultured, sophisticated aristocrat, fascinated alike by the comedy and tragedy of human life, but unquestioning in his social and religious conservatism” (42).

Another distinctive characteristic of the playwright is his obvious interest and competence in music. “In no author are musical allusions more frequent than in Shakespeare” (Squire 32). In the plays and poems there are hundreds of images, metaphors, and passages relating to music, as well as numerous ballads, love songs, folk songs, and drinking songs. The playwright demonstrates a clear technical knowledge of musical theory and practice, writing about the musicians, the instruments, and even the notes (Squire 32–49).

These attributes and characteristics comport precisely with those of the 17th Earl of Oxford — a courtier, aristocrat, and Lord Great Chamberlain of England who was an intimate of both Queen Elizabeth and her Principal Secretary, Sir William Cecil (Lord Burghley), whose daughter he married at his coming-of-age. Oxford was praised for his affection for and competence in music, and for his patronage of musicians and composers, notably John Farmer and William Byrd (Ward 203–04; Anderson 205). However, these are only the most obvious similarities between him and the playwright Shakespeare. The details of his education, his literary and theatrical activities, his personal experiences, his travels, and the people surrounding him all supply strong evidence that he is the author of the Shakespeare canon.

Oxford’s Early Environment and Education

Among Shakespeare scholars, there is general agreement that he was one of the best read and most broadly educated playwrights of the Renaissance. In the words of Emerson, “His mind is the horizon beyond which, at present, we do not see” (254). He displays a wide-ranging familiarity with the literature of Elizabethan England and the continent, as well as with the classics of ancient Rome and Greece. Besides literature, he was also obviously interested in and familiar with a variety of scholarly subjects, such as botany, astronomy, medicine, and philosophy. Scholars have identified hundreds of plays, poems, novels, and histories, by dozens of authors, that he referred to, quoted, or used as sources (Gillespie 521–28). His use of untranslated works in Latin and Greek, as well as his frequent use of words from, and creation of words derived from, those languages, attest to his competence in both (Theobald 14–15).

[pullquote]Oxford’s childhood and adolescence suggest an environment and an upbringing that would have been an ideal preparation for a poet and dramatist.[/pullquote]The facts and circumstances surrounding Oxford’s childhood and adolescence suggest an environment and an upbringing that would have been an ideal preparation for a poet and dramatist, especially one who would write about the characters and subjects that dominate the Shakespeare canon. The tradition of sponsoring playing companies by the de Vere family was in place no later than 1490, during the tenure of John, the 13th Earl (Lancashire 106, 407) — a tradition maintained by Oxford’s father and Edward himself. The author of one of the earliest English history plays, John Bale, wrote it for Oxford’s grandfather in the 1530s and subsequently revised it for a performance for Queen Elizabeth during her visit to Ipswich in 1561 (Harris 71). It is likely that Oxford was in attendance. As a young child he lived with, and was tutored by, Sir Thomas Smith, one of England’s greatest scholars and the owner of an extensive library (Hughes 1, 9). His father’s sister Frances was the widow of Henry Howard, Earl of Surrey, a major poet who is credited with the first sonnets written in the distinctive Shakespearean form, a modification of the Petrarchan sonnet.

Oxford matriculated at Cambridge at age eight, and was later awarded Master’s degrees by both Oxford and Cambridge Universities (Ward 11, 22, 27). In his collection of studies of the Elizabethan drama, Frederick A. Boas refers to “the curious fact that Shakespeare shows familiarity with certain distinctively Cambridge terms” (47–49).[3] In 1562 Oxford’s father died, and the twelve-year-old became a royal ward. He was sent to London to live in the home of Sir William Cecil, later Lord Burghley, Principal Secretary to the Queen. A surviving schedule of Oxford’s rigorous daily schooling in Cecil’s household (Ward 19–20) confirms that he was a student in what G. P. V. Akrigg has called “the best school for boys to be found in Elizabethan England” (25).

The early environment and education of Oxford prepared him to be the writer “Shakespeare” became, and led him to fill his dramas with the same kings and queens, aristocrats, clergymen, and courtiers he saw about him.

When Oxford was in his early teens, his uncle Arthur Golding translated Ovid’s Metamorphoses, probably Shakespeare’s most important source. Oxford had already been recognized by then as a precocious student. In 1563 his tutor, the antiquary, Laurence Nowell, advised Cecil that his services would not much longer be needed (Ward 20). In a translation from the Latin that was dedicated to him in 1564, Oxford was praised for “a certain pregnancy of wit and ripeness of understanding” by his uncle, the classical translator Arthur Golding (Chiljan, “Dedications,” 4).

As the heir to one of England’s oldest earldoms and a member of the Cecil household, Oxford was embedded in an environment that figured prominently in the Shakespeare canon — the royal court and the center of English culture, power, and wealth. “Cecil House was England’s nearest equivalent to a humanist salon …. As a meeting place for the learned it had no parallel in early Elizabethan England” (Dorsten 195).

Besides being the dedicatee of dozens of literary works, Cecil was also one of the premier book and manuscript collectors of the Elizabethan age, and modern scholars have described his extensive library (Jolly 6). There is clear documentation that Oxford purchased a Geneva Bible, and editions of Chaucer and Plutarch, all major sources of Shakespeare’s plays (Ward 33).

Literary and Theatrical Activities

Evidence of Oxford’s literary activity and his association with the Elizabethan theater extends from his teen years to the end of his life. Beginning in 1564, he was the dedicatee of more than two dozen books, including a dozen works of translation and imaginative literature, produced by poets, playwrights, and translators, such as Thomas Watson, Robert Greene, and Arthur Golding. The interests of Shakespeare are reflected in several other books dedicated to the Earl of Oxford — on medicine, on music, and on the military.[4] The Earl was repeatedly cited as a generous patron and a keen reader of poetry and prose, foreign and English, both contemporary and classical.

Poems first appeared in print over the Earl of Oxford’s initials in a widely-read Elizabethan collection, The Paradise of Dainty Devices, published in 1576 and repeatedly reprinted for the rest of the century. These poems have been praised as experimental, innovative, and skilful. According to Professor Steven W. May (despite his own rejection of the Oxfordian theory), Oxford’s youthful poems in Paradise “create a dramatic break with everything known to have been written at the Elizabethan court up to that time” (53). May describes one early poem, in which the author cries out against “this loss of my good name,” as a “defiant lyric without precedent in English Renaissance verse” (53). This eighteen-line cri de coeur has been associated with an accusation made by Oxford’s half-sister Katherine in 1563, when he was thirteen, that he was born of a bigamous marriage, and was therefore illegitimate (Anderson 24; see also here for more discussion).

Oxford’s poems have been linked to Shakespeare by Joseph Sobran (among other scholars), who found hundreds of phrases, lines, and images in 20 of his poems that are repeated one or more times in the Shakespeare canon (231–70). He found hundreds of similar echoes of the canon in Oxford’s letters (170–71).[5] You may further explore, starting here, these hundreds of compelling Shakespearean parallels in Oxford’s early poetry.

At the age of 21, the Earl of Oxford sponsored the translation into Latin of Castiglione’s Il Cortegiano (“The Courtier”) and wrote a prefatory note in Latin to the translator Bartholomew Clerke. The following year he commissioned and wrote an introductory letter to Thomas Bedingfield’s English translation of Cardanus’s De Consolatione (“Cardanus’s Comfort”), a work recognized even by orthodox scholars as “Hamlet’s book” (Craig 17–37; Campbell 17, 133–34). He employed well-known literary men, such as John Lyly, Anthony Munday, and Abraham Fleming as his secretaries, the former two being playwrights (Anderson 482). For almost a decade he maintained an unconventional literary salon near the theater district that was a headquarters for impecunious poets and playwrights (Anderson 156–61).

In 1573 the Cambridge scholar Gabriel Harvey wrote that Oxford’s introduction to Cardanus’s Comfort was an example of “how greatly thou dost excel in letters,” and praised him as the writer of “many Latin verses” and “many more English verses” (Anderson 139). He was cited by name in several different works of literary commentary as a leading poet and playwright. For example, in A Discourse of English Poetry (1586), William Webbe praised him as the “most excellent” of poets at court (Smith I, 243).

The anonymous author of The Arte of English Poesie (1589) asserted that Oxford was among the best of courtly poets who had “written excellently well, as it would appear if their doings could be found out” (Smith II, 65). A separate comment in the same book noted that “very many” such courtiers “suppressed” their writing “or else suffered it to be published without their own names to it, as if it were a discredit for a gentleman to seem learned and to show himself amorous of any good art.”

The judgment of these contemporaries is confirmed by 19th and 20th century critics such as Alexander B. Grosart, William J. Courthope, and Sidney Lee; the latter asserted that Oxford “wrote verse of much lyric beauty” (Looney 124–25; Lee 228).

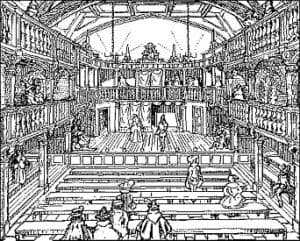

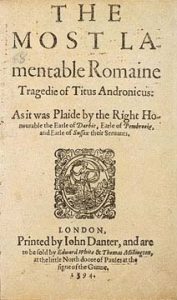

De Vere’s life-long association with the theater, with players, and with playwrights is unquestionable. During the 1580s, and as late as 1602, he sponsored his own playing companies. In 1583 he leased one of the earliest private Elizabethan theaters, the Blackfriars, for the use of his own troupe, the Earl of Oxford’s Boys (Anderson 187–88). In Palladis Tamia (1598), a commonplace book of similes, quotations, and observations on all manner of subjects, Francis Meres included him in a list of the best comic playwrights. However, no play bearing his name has survived, nor is there any surviving record of his name being explicitly associated with any play.

Over a period of more than four decades, repeated opaque suggestions were made that there was an unknown writer behind the Shakespeare name who could not be revealed. In “L’Envoy” to his poem “Narcissus” (1595), Thomas Edwards devoted fifteen stanzas to describing several contemporary poets, identifying each of them by a name from one of their poems. In the three stanzas describing the author “Adon” (a veiled reference to whoever wrote Venus and Adonis), Edwards used such phrases as “in purple robes distained,” “one whose power floweth far,” “the only object and the star,” and “he differs much from men / Tilting under Frieries.” These and other phrases point in general to a leading nobleman, and particularly to the Earl of Oxford (e.g., Stritmatter, “Tilting,” 1, 18–20).

In his pamphlet The Scourge of Folly (1611), the poet John Davies of Hereford addressed “Shake-speare” [sic] as “our English Terence” (II, 26), a comparison very likely referring to the tradition that the comedies of the former slave and Roman playwright Terence were actually written by the aristocrats Scipio Africanus and Gaius Laelius. The assertion was first made in 50 BCE by Cicero in a letter to his friend Atticus (271), and again in the next century by the rhetorician Quintilian (IV 57).

In The Schoolmaster (1570), Roger Ascham repeated the assertion (143–44), as did Montaigne, whose essays were translated by John Florio in 1603 (199). Similar suggestions about a concealed poet were made in 1598 by John Marston in Scourge of Villanie (Ogburn 401–02), and in 1612 by Henry Peacham in Minerva Britanna (Stritmatter, “Minerva”).

These examples do not exhaust the abundant evidence that Oxford was a significant literary figure throughout his lifetime, and that he was referred to as the concealed author behind the Shakespeare pseudonym.

Legal Training and Experience in the Military

Shakespeare’s familiarity with the law and his frequent use of legal language have long been a subject of intense interest. The most recent analysis of the legal terms, concepts, and procedures occurring in the Shakespeare canon conclusively demonstrates that he had an extensive and accurate knowledge of the law (Alexander 110–11). He used more than two hundred legal terms and legal concepts in numerous ways — as case references, as similes and metaphors, images, examples, and even puns — with an aptness and accuracy that can no longer be questioned. In 1567 Oxford matriculated at Gray’s Inn, one of the Elizabethan law colleges. He was a member of the House of Lords for more than thirty years, a juror in two of the most important treason trials of the period, and was involved in legal matters and court suits throughout his life.

Shakespeare’s intimate knowledge of military affairs was noticed in the mid-nineteenth century, and has more recently been fully documented. According to the compiler of a dictionary of his military language, Shakespeare possessed “an extraordinarily detailed knowledge of warfare, both ancient and modern” (Edelman 1). Nearly all the history plays, as well as Othello, Antony and Cleopatra, and Troilus and Cressida, are set in a place and time of armed conflict, and numerous obscure military analogies and references can be found throughout the canon. Several of Shakespeare’s most enduring characters are soldiers or ex-soldiers, including the faux soldier Sir John Falstaff. One of Oxford’s most fervent wishes as a young man was to serve his Queen in the military against her enemies. After missing a chance because of illness, he rode with an English army in the Scottish campaign in 1570 before he was 20, and later faced the Spanish in the Netherlands as Commander of the Horse in 1585 (Anderson 41–43, 204–206).

Shakespeare’s knowledge of the sea and ships is just as striking and comprehensive. According to naval officer A. F. Falconer, there is a ‘surprisingly extensive and exact use of the technical terms belonging to sailing, anchor work, sounding, ship construction, navigation, gunnery and swimming’ in the Shakespeare canon. He adds that ‘Shakespeare does not invent sea terms and never misuses them’ (vii). Again, Oxford had ample opportunity to become familiar with ships and the sea. The trip from the de Vere home in Essex to London was routinely made by ship from the seaside town of Wivenhoe at the mouth of the Colne River, where the de Veres had had an estate for over a century. Oxford made at least two Channel crossings during his 20s and traveled extensively by water in and around Italy during his visit in 1575–76. There is also evidence that he was aboard ship in the preliminary maneuvers against the Spanish Armada in the summer of 1588 (Anderson 223–25).

Thus, three distinctive characteristics that the author of the Shakespeare canon displayed — an authoritative knowledge of the law, the military, and ships and the sea, are readily explained by the record of Oxford’s activities. No other candidate for the authorship, including Shakespeare of Stratford, had these kinds of personal experiences.

France and Italy Prominent in the Canon

The concordance between Shakespeare’s detailed knowledge of the language, culture, and geography of Italy and France and the travels of Edward de Vere in those countries is one of the strongest indicators that they were one and the same person. It is well-known that Elizabethan imaginative literature, especially its drama, was heavily indebted to Italian sources and models, and made use of such devices from Italian drama as the chorus, the dumb show, and the play-within-the play (Grillo 65). To no other writer did this apply more than to Shakespeare. Fully a third of the plays in the canon take place in Italy, including ancient Italy, and another half dozen in France. In addition, more than a dozen are wholly or partially derived from Italian plays or novels.

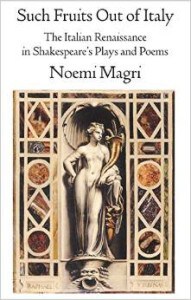

Scholars have repeatedly documented Shakespeare’s unexplained familiarity with the geography, social life, and local details of many places in Italy, especially northern Italy.[6] ‘When we consider that in the north of Italy he reveals a … profound knowledge of Milan, Bergamo, Verona, Mantua, Padua and Venice, the very limitation of the poet’s notion of geography proves that he derived his information from an actual journey through Italy and not from books’ (Grillo 146). Italian scholar Noemi Magri has identified the locales and documented the accuracy of numerous details in Two Gentlemen of Verona and The Merchant of Venice .[7]

Nor is Shakespeare’s knowledge of Italy limited to details of geography and local custom. It is clear that he directly observed and was profoundly affected by Italian painting and sculpture, and used several specific works — murals, sculptures, and paintings — as the bases for incidents, characters, and imagery in his plays and poems. For instance, the language and imagery in The Winter’s Tale, Love’s Labour’s Lost, Venus and Adonis, and Lucrece have been traced to the sculpture and murals of Giulio Romano in Mantua’s Ducal Palace and Palazzo Te, and elsewhere in the same city (Hamill, Ghosts 86–92). The original Italian paintings that inspired three of the ‘wanton pictures’ described in The Taming of the Shrew (Ind. 2.49–60) have been located and identified with a high degree of certainty.[8] During the 1570s they could be seen at three places on Oxford’s itinerary — Fontainebleau, Mantua, and Florence (Magri 4–12).

Among the most striking examples of Shakespeare’s knowledge of Italy are the acute observations he makes about Italian attitudes and behavior. As de Vere biographer Mark Anderson points out (xxx), the dramatist ‘knew that Florence’s citizens were recognized for their arithmetic and bookkeeping’ (Othello 1.1.19–31); ‘he knew that Padua was the “nursery of arts,” and that Lombardy was ‘the pleasant garden of great Italy’ (The Taming of the Shrew I.i.1–4); and he knew that ‘a dish of baked doves was a time-honored northern Italian gift’ (The Merchant of Venice II.ii.135–6). Moreover, these observations are made in a natural and unobtrusive way and are entirely appropriate in their context. Critics have observed that in plays by some other dramatists, such as Jonson and Webster, such details are intrusive and unsubtle, as if they were taken from books (Furness 72–3; Elze 270–7).

After waiting several years for permission from the Queen to leave England, Oxford was allowed to travel to Paris and then to Italy via Strasbourg in February 1575. After leasing quarters in Venice, he toured Italy for more than a year, visiting nearly all the locations in Shakespeare’s Italian plays, including Milan, Padua, Verona, Florence, Mantua, and Palermo (Anderson 74–107). Significantly, the Italian cities and city-states that Oxford did not visit, such as Bergamo, Naples, Ravenna, etc., are not mentioned in the Shakespeare canon. Shakespeare’s Italy, it turns out, is the Italy that Oxford visited.

Why the Anonymity?

One of the central questions about the case for Oxford that has not been definitively answered is why he concealed his authorship of the canon and used a pseudonym. Of the several possible reasons for this, the most obvious is the so-called ‘stigma of print,’ the idea that the creative work of self-respecting aristocrats, including most courtiers, was merely a pastime, a leisure activity. Allowing it to appear in print over their own names suggested a crass seeking of publicity or even monetary compensation.[9] The stigma applied especially to playwriting. Even late into Elizabeth’s reign ‘the condemnation of public plays and the people concerned with them was fairly general’ (Bentley 43).

Another reason for anonymity was simple custom. Most of the plays performed during Elizabeth’s reign were never published, and most of those printed appeared without an author’s name (Maxwell 5–6). Plays now attributed to Lyly, Peele, Greene, Kyd, Marlowe, Heywood, Drayton, Shakespeare, and dozens of others were first printed anonymously. As Alfred Hart wrote about Elizabethan printed plays, ‘It is correct to state that anonymity was the rule rather than the exception’ (6). There is no evidence that the author of the Shakespeare canon had any interest or role in the publication of his plays or poems. Nor is there any record that he objected or intervened when corrupt or allegedly ‘pirated’ editions were published (Price ‘Unorthodox,’ 129–30, 170). But it is possible that he had a hand in the publication of his two narrative poems, Venus and Adonis (1593) and Lucrece (1594), both of which appear to have been carefully edited.

A third reason for anonymity, one that appears to apply directly to the Earl of Oxford, has to do with his position as hereditary Lord Great Chamberlain of England who had a close association with Queen Elizabeth. Many prominent figures in the court and in the highest levels of government were the targets of satire in the Shakespeare plays, some of it extremely disparaging. Knowledge that the author was a genuine insider who had a personal acquaintance with the subjects of his satire would make them easier to identify and would lend credence to his mocking portraits. In this case, it might have been William Cecil, or even the Queen, who required that Oxford remain anonymous.

Finally, Oxford may have imposed anonymity upon himself, or had it imposed by higher authorities, because of some aspect of his personal behavior. Late in 1580, he confessed to the Queen that he and some others had been reconciled to the Catholic Church. This led to the arrest of two of his acquaintances, Henry Howard and Charles Arundel, who then unleashed a lengthy screed of invective against him that accused him of everything from treason to pederasty (Anderson 165–9).

In March of the next year, Anne Vavasour, a 19-year-old lady-in-waiting to the Queen, gave birth to Oxford’s son, the pregnancy being actually her second by him. The three of them were sent to the Tower, where Oxford remained until released by the Queen in June, but he was banned from the court for another two years (Anderson 172–3). At the time, Oxford had been living apart from his wife for five years because of his suspicion that she had betrayed him with another man. Although he reunited with her in 1582, these scrapes and scandals, and certain other indignities, may have led him to consider himself in disrepute and disgrace, which, along with regret and awareness of imminent death, are the themes of a dozen or more of his sonnets (Cossolotto 8–12).

It appears that Oxford assented to the publication of Venus and Adonis and Lucrece, and wrote the very personal dedications to Henry Wriothesley, 3rd Earl of Southampton, who is widely believed to be the Fair Youth of the Sonnets. It may have been that he was anxious that his relationship with him, whatever it was, not be known to the public, and for this reason caused the dedications to be signed with the pseudonym ‘William Shakespeare.’ The name recalls the Greek goddess Athena, who was said to have sprung from the brow of Zeus brandishing a spear. She was the protector of Athens, the birthplace of classical drama, and was widely perceived as both a patron goddess of poets and fearless warrior in battle.[10] As such, she was most likely the inspiration behind a common English name that concealed a nobleman and a dramatist who had martial aspirations.

How, when, and why the pseudonym came to be associated with the man from Stratford with a similar name is unknown. What is clear is that it continued to be used after Oxford’s death in 1604. The perpetrators appear to have been his surviving relatives, who may have had the same motivation as he did. Their roles in the production of the First Folio are described below.

Oxford’s Life and Circumstances in the Plays

Every work in the Shakespeare canon contains allusions to circumstances, events, and people in Oxford’s life. Portraits of him, his family, and his contemporaries have been identified in most of them by both orthodox and Oxfordian scholars. These allusions and portraits are ‘too numerous, consistent, complex and intimate to be mere coincidences’ (Malim, Will). Of all the plays, Hamlet contains the most autobiographical material, including characters that appear to represent Oxford’s father-in-law William Cecil (Polonius), his wife Anne Cecil (Ophelia), Cecil’s son Robert (Laertes) and Oxford himself, whose circumstances, interests, and experiences are clearly depicted in the portrait of Prince Hamlet (Sobran 189–95). Oxford can also be identified as Bertram in All’s Well That Ends Well (Ogburn 489–91) and Timon in Timon of Athens (Anderson 323–4). His street quarrel with the Knyvet family is echoed in Romeo and Juliet (Anderson 180–1).

Twelfth Night is perhaps the play that connects Oxford with the Shakespeare canon more strongly than any other, for two reasons. In the first place, the plot and the characters depict an episode in which Oxford had a strong interest — the courtship of Queen Elizabeth (Olivia) by the French Duc d’Alençon (Duke Orsino) in 1579. Also identifiable in the cast are Oxford’s sister Mary (Maria), his friend Peregrine Bertie (Sir Toby Belch), the poet Sir Philip Sidney (Sir Andrew Aguecheek), Sir Christopher Hatton (Malvolio), and Oxford himself, whom the dramatist portrayed in Feste, the professed fool in Olivia’s court (Clark 220–232).[11]

Secondly, in 1732 the antiquarian Francis Peck described a manuscript that he proposed to publish as ‘a pleasant conceit of Vere, earl of Oxford, discontented at the rising of a mean gentleman in the English court, circa 1580,’ a statement that particularly applies to Twelfth Night. Although this manuscript was never published and is probably lost, it was identified by Peck as belonging to the library of Abraham Fleming (c. 1552–1607), a London translator, poet, historian, and clergyman who was a secretary to the Earl of Oxford, c.1580 (Anderson 486).

Oxford’s anger and despair at the infidelity of Anne, which he later came to doubt, is a recurring theme in at least four plays — Measure for Measure, Othello, Cymbeline, and The Winter’s Tale, in all of which a husband is deceived by slanders against his innocent wife (Ogburn 566–71). The hot-tempered and blunt talking Welshman Fluellen in Henry V has been identified by Oxfordian and orthodox scholars alike as Sir Roger Williams, a follower of the Earl of Oxford (Barrell 59–62). A prank ambush of two of Lord Burghley’s servants by three of Oxford’s men at Gad’s Hill near Rochester in 1573 is recapitulated in 1 Henry IV (II.ii) by Falstaff and three of Prince Hal’s servants (Ogburn 529). The Merchant of Venice, King Lear, Twelfth Night, The Taming of the Shrew, The Tempest, and others contain names, incidents, and situations that can be found in the biography of Edward de Vere (Anderson xxvii).

Shakespeare’s Sonnets are an especially rich source of associations with Oxford. They are filled with autobiographical details and references that are directly linked to what is known about his life: the author’s intention that his identity remain unknown — ‘My name be buried where my body is’ (72); his lameness, his shame and his ‘outcast state’ (89, 129, 29); his preoccupation with the ravages of time, old age and his own imminent death (16, 62, 73). Several sonnets suggest that the writer is a nobleman (91, 125), and Sonnet 76 contains an unmistakable reference to ‘E. Vere’ — ‘That every word doth almost tell my name.’ Most scholars and editors agree that the Sonnets are in some way autobiographical, but beyond that opinions vary widely as to their actual meaning.

Some scholars have found evidence of homosexual love of the Fair Youth by the Sonnets author, and evidence of the same predisposition in several of the plays (Sobran 98–100, 198–201; Hamill, Sexuality 49–53). Others detect a father-son relationship between them (Ogburn 342–6; Whittemore, ‘Chronicles’). There are several significant connections between Oxford and Henry Wriothesley, the presumed subject of the Fair Youth sonnets, but the role of the young man, whether patron, son, lover, or merely dear friend, is still a much-debated question. Regardless of these uncertainties, however, the basic facts about the Sonnets supply further evidence that they were written by Edward de Vere.

Dating the Plays and Oxford’s Death in 1604

Orthodox scholars typically dismiss the Oxfordian argument with the claim that several of Shakespeare’s plays, as many as a dozen, were written after 1604, the year of Oxford’s death. But no definite post-1604 allusion or source has been shown to be essential to any Shakespeare play. In no play is there a reference to any natural phenomenon, scientific discovery, or topical event that occurred after 1604, nor is there a reference to anything published after 1604 (Whalen 75–6).

Despite intense research and analysis, scholars have been unable to establish an unambiguous date of composition for any Shakespeare play. Registration, publication, and performance dates have been obtained from various documents, but they can only indicate a terminus ante quem, a date before which the play must have been written. It is clear that several canonical plays were written many years before they were mentioned anywhere (Sobran 161). Eighteen plays that appeared in the First Folio in 1623 had never been printed before, and for three of them, Coriolanus, Timon of Athens, and All’s Well That Ends Well, there is no surviving record of any kind before that date.

There is evidence, however, that the playwright ceased writing in 1604. Critics have noted Shakespeare’s frequent references to contemporary astronomical events and scientific discoveries, such as the supernova of 1572, remarked upon by Bernardo in Hamlet (I.i.36–8), William Gilbert’s theory of geomagnetism, which he published in 1600, referred to twice in Troilus and Cressida (II.ii.179 and IV.ii.104–5), and the lines in 1 Henry VI that allude to the uncertainty of the orbit of Mars (I.ii.1–2).[12] But similar events and discoveries that occurred after 1604 are absent from the canon. The discovery of Jupiter’s moons (by Galileo in 1610), the explanation of sunspots (also by Galileo, in 1612), and the invention of the working telescope (1608), for instance, go unmentioned in the plays supposedly written after 1604.

Another indication that the author wrote nothing after 1604 is the fact that of 43 major sources of Shakespeare’s plays, all but one, the so-called ‘Strachey Letter’ (discussed below), were published before Edward de Vere died, in 1604 (Sobran 156–7). In fact, a few orthodox scholars have even concluded that Shakespeare stopped writing in 1604.[13]

The most persistent argument for a post-1604 Shakespeare play is that for The Tempest, which was mentioned for the first time in a record of its performance at court in 1611. Its earliest appearance in print was in the First Folio. For many decades, orthodox critics have claimed that the travel narratives of Sylvester Jourdain (1610) and William Strachey were the sources for the storm and shipwreck material in The Tempest. But recent research has demonstrated convincingly that the “Strachey Letter” (which was not actually published until 1625) could not have been written and taken to London in time to be used as a source for the play. The precise details and language of the storm and shipwreck scenes appear to have as their sources the play Naufragium by Erasmus, published in 1518, and a collection of travel narratives, The Decades of the New Worlde, translated from the Latin by Richard Eden.[14] Significantly, Eden was a friend and former student of Sir Thomas Smith, with whom Oxford was living in 1555, the year that Decades was published (Hughes 9). A definitive 2013 study by Professor Roger Stritmatter and Lynne Kositsky, building on this well-documented evidence, has utterly demolished the idea that The Tempest necessarily (or even likely) was written after 1604.

Oxford and The First Folio

The evidence that the author of the canon was actually the Earl of Oxford continued to accumulate after his death in 1604. The mysterious dedication to Shake-speare’s Sonnets, published in 1609, with its enigmatic phrase—’our ever-living poet,’ suggested that the author was dead (Price ‘Unorthodox,’ 145–6). An even more pointed message appeared in the cryptic epistle titled ‘A never writer, to an ever reader. News’ that was added to the second version of the Troilus and Cressida quarto published in the same year. The phrase is easily read as ‘an E. Vere writer to an E. Vere reader.’ Moreover, the epistle refers to the ‘scape’ of the manuscript from certain ‘grand possessors,’ suggesting that, Oxford being dead, someone other than the author was in control of his plays.

The collection of Shakespeare’s plays published in 1623, the First Folio, gives every appearance of being the fruit of twenty years of association among Ben Jonson, the three de Vere daughters, Elizabeth, Bridget, and Susan, and the Herbert brothers, William, 3rd Earl of Pembroke and Philip, 1st Earl of Montgomery. Both Oxford’s son, Henry Vere (b. 1593), and his friend and close ally Henry Wriothesley (b. 1573), 3rd Earl of Southampton and dedicatee of Venus and Adonis and Lucrece, were also closely associated with the Herbert brothers.

In 1590, Elizabeth Vere, Oxford’s oldest daughter, was proposed by her grandfather William Cecil as the wife of Henry Wriothesley, who had entered Cecil’s household as a nine-year-old ward in 1582 (Akrigg 20–22). Wriothesley is generally regarded as the addressee of the first seventeen of Shakespeare’s sonnets — the marriage sonnets.

If this belief is correct, they failed to convince him, and he avoided the marriage. The parents of William Herbert, and Edward de Vere himself, favored the marriage of William to de Vere’s second daughter Bridget, but in 1598 she married someone else (Anderson 313–14). In 1604 the younger Herbert, Philip, married Oxford’s youngest daughter Susan. During the next few years, Susan, as well as other ladies of the court, performed in several of Jonson’s masques, and she was the subject of one of the epigrams that appeared in his Works (1616). The association of Jonson and William Herbert began about 1605, and a decade later Jonson dedicated to him the Epigrams section of his Folio (Riggs 179, 226). In 1615, after a determined campaign for the position, Herbert obtained the office of Lord Chamberlain of the Household, and gained control the Revels Office, as well as the playbooks of the King’s Men, who had performed many of the Shakespeare plays.

The orchestration and financing of the First Folio by the Herbert brothers, and editorial work by Ben Jonson are additional strong indications that Oxford was the author of the plays.

The names of two former King’s Men actors, John Heminges and Henry Condell, appear under the dedication of the First Folio to the two Herbert Earls, who may have financed its publication. Although Heminges and Condell claim to have collected the plays, it is far more likely that this was done by the Folio’s publishers. And there is strong evidence that it was Ben Jonson who not only edited the plays but also wrote both the dedication and the subsequent epistle that also bore the two actors’ names (Price ‘Unorthodox’ 170–4).

The orchestration and financing of the First Folio by the Herbert brothers, and editorial work by Ben Jonson, who had a long-standing association with them and with Oxford’s daughter Susan, are additional strong indications that Oxford was the author of the plays. Furthermore, an extensive analysis of the prefatory material in the First Folio concludes that it is ‘littered with hints that the poet was a man of rank . . .’ (Price ‘Unorthodox’ 176). The deliberate concealment of the actual author and the allusions to Shakespeare of Stratford in the First Folio accord with the efforts made by Oxford during his lifetime to remain anonymous and, after 1593, to allow his work to be credited to a man whose name happened to be similar to his pseudonym.

It is only in, and not until, the First Folio of 1623 that the few ambiguous phrases appear that purport to connect the Shakespeare plays with the William Shakespeare of Stratford who died in 1616. There is substantial evidence that the only other connection — the putative monument to the author in Stratford’s Holy Trinity Church — was originally a bust of John Shakespeare that was altered to represent his son (Kennedy). It is upon this scanty evidence that the entire case rests for the Stratford businessman’s authorship of the world’s most illustrious dramatic canon.

The Future of the Oxfordian Theory

Cases of mistaken or concealed identity of authors and the people they write about are relatively common in literature. But it is rare that a literary deception has had an impact as important and as widespread as the Shakespeare hoax. Emerson was one of the earliest to recognize its importance when he asserted, in 1854, that the Stratfordian narrative was improbable, and that the identity of the writer posed ‘the first of all literary problems’ (Deese 114).[pullquote]Emerson was one of the earliest to recognize its importance when he asserted, in 1854, that the Stratfordian narrative was improbable, and that the identity of the writer posed ‘the first of all literary problems’[/pullquote]The accumulation of evidence for Oxford, here much condensed and summarized, is the most comprehensive and detailed solution to the ‘problem.’ It is hard to believe that it will not eventually result in the acceptance of Edward de Vere as the genuine Shakespeare.

When this occurs, all the biographies of the Stratford man, and at least one of Oxford, will become comical literary curiosities. Every Stratfordian analysis of every play and poem will have to be rewritten, and dozens of speculations about sources, meanings, characters, and allusions will prove to be incorrect. The canon will be expanded, and its beginning and ending dates corrected to coincide more closely with the reign of Elizabeth.

More than that, the history of Elizabethan drama and poetry will be drastically revised by the revelation that Sidney, Lyly, Watson, Daniel, Greene, Kyd, Lodge, and Marlowe, all younger and less talented than de Vere, did not influence, and were not precursors of, Shakespeare, but the reverse.[15] Most of the plays and poems will be redated at least fifteen years earlier, changing antecedents into derivations and lenders into borrowers. The map of Elizabethan creative literature will be turned upside-down or, more properly, right-side-up, and this extraordinary man will finally be accorded his rightful place in the history of drama, of poetry, and of the language itself.

Endnotes

- “Shakespeare” Identified in Edward de Vere the Seventeenth Earl of Oxford (1920).⇑

- These facts are documented in Jiménez, “Eyewitnesses.”⇑

- Although Boas claims that Shakespeare was more familiar with Oxford than anywhere else in England, except Stratford and London, he is able to cite only two references to it in the canon, both general in nature, in Henry VIII and The Taming of the Shrew (46–47). Furthermore, the Welsh-hating Dr. Caius, who is a significant character in The Merry Wives of Windsor, was obviously based on Dr. John Caius, a scholar and physician who had a long association with Gonville College, Cambridge (DNB). See also Gilvary, “Queens’ College Cambridge.”⇑

- The Practice of New and Old Physic by George Baker (1599), Plainsong Diverse & sundry (1591) and English Madrigals (1599) by John Farmer, and Defense of the Military… (1579) by Geffrey Gates. See Chiljan, Dedications, pp. 41, 94, 98. John Harrison, the publisher of the Gates volume, also published Venus and Adonis and Lucrece.⇑

- The most comprehensive treatment of the subject is Fowler, 1986.⇑

- Among the earliest to write on the subject was Karl Elze in 1874.⇑

- Magri’s articles can be found in Great Oxford, Richard Malim ed., pp. 66–78 and pp. 91–106.⇑

- Quotations from Shakespeare are from The Riverside Shakespeare, 2d ed. G. Blakemore Evans, ed.⇑

- The concept is explained more fully in Price, “Stigma.” See also Sheavyn at 162–63, 168.⇑

- The Elizabethan association of Athena with spear-shaking and dramatic poetry is best explained in Paul, “Pallas-Minerva = Spear-Shaker.”⇑

- See also Farina at 82–87.⇑

- These are explained more fully in Altschuler, “Searching.”⇑

- Anderson cites several at 397–98 and 572.⇑

- See Stritmatter and Kositsky, “Voyagers.”⇑

- Among the revelations of Michael Egan’s The Tragedy of Richard II, Part One (2006) is that Marlowe’s Edward II follows rather than precedes Shakespeare’s treatment of the Richard II story.⇑

Bibliography

Akrigg, George P.V. Shakespeare and the Earl of Southampton. London: Hamish Hamilton, 1968.

Alexander, Mark A. “Shakespeare’s Knowledge of Law: A Journey Through the History of the Argument.” The Oxfordian 4 (2001), 51–113.

Altschuler, Eric. “Searching for Shakespeare in the Stars.” 1998 (available online).

Anderson, Mark. Shakespeare by Another Name. New York: Gotham Books, 2005.

Ascham, Roger. The Schoolmaster (1570). Lawrence V. Ryan, ed. Ithaca, N.Y.: Cornell University Press, 1967.

Barrell, Charles Wisner. “Shakespeare’s Fluellen Identified as a Retainer of the Earl of Oxford.” Shakespeare Fellowship Newsletter, 2:5 (August 1941), 59–62 (also available on the Shakespeare Authorship Sourcebook website).

Bate, Jonathan. Soul of the Age: The Life, Mind and World of William Shakespeare. Viking (U.K.), 2008 (republished in U.S. as Soul of the Age: A Biography of the Mind of William Shakespeare, Random House, 2009).

Bentley, Gerald E. The Profession of Dramatist in Shakespeare’s Time, 1590–1642. Princeton: Princeton University Press, 1971.

Boas, Frederick A. Shakespeare and the Universities. Oxford: Basil Blackwell, 1923.

Campbell, Lily B. Shakespeare’s Tragic Heroes, Slaves of Passion. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1952.

Chiljan, Katherine. Book Dedications to the Earl of Oxford. San Francisco, 1994.

_____. Letters and Poems of Edward, Earl of Oxford. San Francisco, 1998.

Cicero, Marcus Tullius. Cicero’s Letters to Atticus. Harmondsworth: Penguin Books, 1978.

Clark, Eva Turner. Hidden Allusions in Shakespeare’s Plays. New York: William Farquhar Payson, 1931.

Cossolotto, Mathew. “Shakespeare’s ‘Last Will’ Sonnets. Twelve Poems Convey the Poet’s Wishes.” Shakespeare Oxford Newsletter 41:1 (Winter 2005), 8–12.

Craig, Hardin. “Hamlet’s Book.” Huntington Library Bulletin 6 (Nov. 1934), 17–37.

Davies, John. The Complete Works of John Davies of Hereford. 2 vols. A. B. Grosart, ed. Edinburgh: T. and A. Constable, 1878.

Deese, Helen R. “Two Unpublished Emerson Letters: To George P. Putnam on Delia Bacon and to George B. Loring.” Essex Institute Historical Collections 122:2 (April 1986), 101–125.

Dorsten, Jan, van. “Literary Patronage in Elizabethan England: The Early Phase.” In Patronage in the Renaissance, Guy F. Lytle & Stephen Orgel, eds. Princeton: Princeton University Press, 1981. 191–206.

Edelman, Charles. Shakespeare’s Military Language: A Dictionary. London: Athlone Press, 2000.

Elze, Karl. Essays on Shakespeare. London: Macmillan, 1874.

Emerson, R. W. Emerson’s Poetry and Prose. Joel Porte & Saundra Morris, eds. New York: W. W. Norton, 2001.

Evans, G. Blakemore, ed. The Riverside Shakespeare. 2d ed. Boston: Houghton Mifflin, 1997.

Falconer, A. F. A Glossary of Shakespeare’s Sea and Naval Terms Including Gunnery. London: Constable, 1965.

Farina, William. De Vere as Shakespeare: An Oxfordian Reading of the Canon. Jefferson, N.C.: McFarland, 2006.

Fowler, William Plumer. Shakespeare Revealed in Oxford’s Letters. Portsmouth, N.H.: Peter E. Randall, 1986.

Furness, H. H. A New Variorum Edition of Shakespeare,The Merchant of Venice. (1868) New York: American Scholar Publications, 1965.

Gillespie, Stuart: Shakespeare’s Books: A Dictionary of Shakespeare’s Sources. London: Athlone Press, 2001.

Gilvary, Kevin. “Queens’ College Cambridge and the Henry VI Plays.” De Vere Society Newsletter 15:2 (June 2008), 5–6.

Grillo, Ernesto. Shakespeare and Italy. Glasgow: Robert Maclehose, 1949.

Hart, Alfred. Stolne and Surreptitious Copies: A Comparative Study of Shakespeare’s Bad Quartos. Melbourne: Melbourne University Press, 1942.

Hamill, John. “The Ten Restless Ghosts of Mantua: Shakespeare’s Specter Lingers over the Italian City.” In “Report My Cause Aright”: The Shakespeare Oxford Society Fiftieth Anniversary Anthology, 1957–2007. Shakespeare Oxford Society, 2007. 86–102.

_____. “Shakespeare’s Sexuality and How It Affects the Authorship Issue.” The Oxfordian 8 (2005), 25–59 (PDF version here).

Harris, Jesse W. John Bale: A Study in the Minor Literature of the Reformation. Urbana: University of Illinois Press, 1940.

Hughes, Stephanie Hopkins. “Oxford’s Childhood Part II: The First Four Years With Smith.” Shakespeare Oxford Newsletter 42:3 (Fall 2006), 1, 5–15.

Jiménez, Ramon. “Ten Eyewitnesses Who Saw Nothing: Shakespeare in Stratford and London.” SOF website, 2011.

Jolly, Eddi. ” ‘Shakespeare’ and Burghley’s Library—Biblioteca Illustris: Sive Catalogus Variorum Librorum.” The Oxfordian 3 (2000), 3–18.

Kennedy, Richard. “The Woolpack Man: John Shakespeare’s Monument in Holy Trinity Church, Stratford-on-Avon.” Online: http://webpages.charter.net/stairway/WOOLPACKMAN.htm.

Kositsky, Lynne & Roger Stritmatter. On the Date, Sources, and Design of Shakespeare’s The Tempest. McFarland, 2013.

Lancashire, Ian. Dramatic Texts and Records of Britain: A Chronological Topography to 1558. Toronto: University of Toronto Press, 1984.

Lee, Sidney. “Vere, Edward de, seventeenth Earl of Oxford.” Dictionary of National Biography. v. 58. London: Smith, Elder, 1885–1906.

Looney, John Thomas. “Shakespeare” Identified in Edward de Vere the Seventeenth Earl of Oxford. London: Cecil Palmer, 1920.

Magri, Noemi: “Shakespeare and Italian Renaissance Painting: The Three Wanton Pictures in The Taming of the Shrew.” De Vere Society Newsletter (May 2005), 4–12.

_____. Such Fruits Out of Italy. Germany: Laugwitz Verlag, 2014.

Malim, Richard. “They Haven’t the Necessary Will.” Letter, The Spectator 280 (9 January 1999), 24.

_____ et al. eds. Great Oxford: Essays on the Life and Work of Edward de Vere, 17th Earl of Oxford, 1550–1604. Tunbridge Wells, U.K.: Parapress, 2004.

Maxwell, Baldwin. Studies in the Shakespeare Apocrypha. New York: Greenwood Press, 1956.

May, Steven W. The Elizabethan Courtier Poets: The Poems and Their Contexts. Columbia: Missouri University Press, 1991 (republished Pegasus Press, University of North Carolina at Asheville, 1999).

Montaigne, Michel de. The Essays of Montaigne. John Florio trans. New York: Modern Library, 1933.

Ogburn, Charlton. The Mysterious William Shakespeare: The Myth and The Reality. 2d ed. McLean, Va.: EPM Publications, 1992.

Paul, Christopher. “Pallas-Minerva = Spear-Shaker.”

Price, Diana. Shakespeare’s Unorthodox Biography: New Evidence of an Authorship Problem. Westport, Conn.: Greenwood Press, 2001 (revised and independently republished, 2012).

_____. “The Mythical ‘Myth’ of the Stigma Of Print.” Online: http://www.shakespeare-authorship.com/resources/stigma.asp.

Quintilian. The Institutio Oratoria of Quintilian. 4 vols. H. E. Butler trans. New York: William Heinemann, 1922.

Riggs, David. Ben Jonson: A Life. Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 1989.

Sheavyn, Phoebe A.B. The Literary Profession in the Elizabethan Age. Manchester: Manchester University Press, 1909.

Smith, G. Gregory, ed. Elizabethan Critical Essays. 2 v. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1904.

Sobran, Joseph. Alias Shakespeare: Solving the Greatest Literary Mystery of All Time. New York: Simon & Schuster [Free Press], 1997.

Spurgeon, Caroline F. E. Shakespeare’s Imagery and What It Tells Us. 1935. Boston: Beacon Press, 1958.

Squire, W. Barclay. “Music.” In Shakespeare’s England, v. 2, Walter A. Raleigh, Sidney Lee & C. T. Onions eds. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1916. 15–49.

Stritmatter, Roger. “The Not-Too-Hidden Key to Minerva Britanna.” Shakespeare Oxford Newsletter 36:2 (Summer 2000), 1, 9–15, 17.

_____. ” ‘Tilting Under Frieries’: Narcissus (1595) and the Affair at Blackfriars.” Cahiers Élisabéthains 70:1 (Autumn 2006), 37–42; also in Shakespeare Matters 6:2 (Winter 2007), 1, 18–20.

_____ & Lynne Kositsky. “Shakespeare and the Voyagers Revisited.” Review of English Studies 58 (2007), 447–72.

_____ & Lynne Kositsky. See also Kositsky & Stritmatter (on The Tempest).

Theobald, William. The Classic Element in the Shakespeare Plays. London: Robert Banks, 1909.

Trevor-Roper, Hugh. “What’s in a Name?” Réalités no. 144 (Nov. 1962), 41–43.

van Dorsten. See Dorsten, Jan, van.

Ward, Bernard M. The Seventeenth Earl of Oxford: 1550–1604. London: John Murray, 1928.

Whalen, Richard F. “A Dozen Shakespeare Plays Written After Oxford Died? Not Proven!” The Oxfordian 10 (2007), 75–84 (PDF version here).

Whitman, Walt. The Complete Poetry and Prose of Walt Whitman. 2 vols. New York: Pellegrini & Cudahy, 1948.

Whittemore, Hank. “Abstract and Brief Chronicles.” Shakespeare Oxford Newsletter 35:2 (Summer 1999), 1, 10–14, 22.

Ramon Jiménez is the author of Shakespeare’s Apprenticeship: Identifying the Real Playwright’s Earliest Works (2018) (published by McFarland and also available on Amazon), a landmark study of several early Shakespeare plays and their revolutionary implications for the authorship question. He has also written two acclaimed histories of ancient Rome, both book club selections — Caesar Against the Celts (Da Capo, 1996) and Caesar Against Rome: The Great Roman Civil War (Praeger, 2000) — as well as several important articles including “Ten Eyewitnesses Who Saw Nothing: Shakespeare in Stratford and London” (2011), “Shakespeare by the Numbers: What Stylometrics Can and Cannot Tell Us” (2011), and “An Evening at the Cockpit: Further Evidence of an Early Date for Henry V” (2016), showing that Shakespeare’s Henry V was probably written and performed no later than 1584. In 2020, he published an important new article updating his work on Shakespeare’s early writings.

Ramon’s scholarly articles have appeared in The Oxfordian, the Shakespeare Oxford Newsletter, and in the anthology Shakespeare Beyond Doubt? (Shahan & Waugh eds. 2013). He and his wife, Joan Leon, are both former Trustees of the SOF and were jointly honored as Oxfordians of the Year in 2018. Ramon has also received the Award for Distinguished Shakespearean Scholarship at the Shakespeare Authorship Studies Conference at Concordia University in Portland, Oregon.

———————————————

Published on the SOF website Sept. 1, 2011, updated 2021. Originally published in The Oxfordian, v. 11 (2009), pp. 45–64 (PDF version here); republished on the SOF website Sept. 1, 2011. In addition to this in-depth essay of about 8,500 words, see Tom Regnier’s 2,500-word summary of the “Top 18 Reasons Why Edward de Vere (Oxford) Was Shakespeare.” See also the SOF “Shakespeare Authorship 101” page for a concise overview of reasons to doubt that William Shakspere of Stratford-upon-Avon wrote any of the plays or poems in the first place (and a concise overview of the case for Oxford).

Membership dues cover only a fraction of our budget, including all our research, preservation and programming. Please support the SOF by making a gift today!

Blue Boar Tavern: Wassail Q&A

Tuesday Dec. 17, 8pm E / 5pm P

Sign up below for event invites!