Top 18 Reasons Why Edward de Vere (Oxford) Was Shakespeare

History has left many clues indicating that Edward de Vere, 17th Earl of Oxford (1550–1604), wrote plays and poetry under the pen name “William Shakespeare.”

These clues, taken together, add up to a very strong case for Oxford as the true author of Hamlet, King Lear, the Sonnets, and other works traditionally attributed to the man from Stratford. Following are some of the main reasons for thinking Oxford was Shakespeare.

#1. Hidden Writer

Edward de Vere (Oxford) was known during his lifetime as a secret writer who did not allow his works to be published under his name. In 1589, the anonymous author of The Arte of English Poesie stated: “I know very many notable gentlemen in the court that have written commendably and suppressed it … or else suffered it to be published without their own names to it, as if it were a discredit for a gentleman to seem learned and to show himself amorous of any good art.” This 1589 book also referred to “courtly makers, noblemen … who have written excellently well, as it would appear if their doings could be found out and made public with the rest. Of which number is first that noble gentleman Edward Earl of Oxford …” (emphases added). Francis Meres said in 1598 that Oxford was one of the best writers of comedy. Yet no comedies have come down to us under his name.

#2. “Shakespeare” as a Pseudonym

In a 1578 Latin oration, Gabriel Harvey said of Oxford, “vultus tela vibrat,” which may be translated as “thy countenance shakes spears.” This may have been an inspiration for the later use of “Shakespeare” as a pen name. Pseudonymity was so common in the Elizabethan Era that is has been called “the Golden Age of pseudonyms.” Archer Taylor and Frederic J. Mosher, in their seminal book on pseudonymous writings, The Bibliographical History of Anonyma and Pseudonyma (University of Chicago Press, 1951), stated: “In the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries, the Golden Age of pseudonyms, almost every writer used a pseudonym at some time or other during his career.”

Pseudonyms were important because a person could be punished for saying things that displeased the authorities. For example, a man with the sadly fitting name of John Stubbs had his hand cut off because he wrote that Queen Elizabeth I was too old to marry. People in the nobility had an additional reason for hiding their identities if they wrote poetry (which was considered frivolous) or plays for the public stage (which were considered beneath a nobleman’s dignity). See quotations above from The Arte of English Poesie (1589).

“Shakespeare,” as a pen name, could be a reference to Athena, the Greek goddess of wisdom who came to be viewed during the Renaissance as a patron of the arts and learning. She is often depicted shaking a spear. Pseudonyms were used because writings that offended the authorities could subject an author to punishment. Also, where the nobility were concerned, it was considered beneath their dignity to publish poetry, which was deemed frivolous, or plays for the public theatres, which were scandalous places where thievery, prostitution, and gambling occurred.

#3. Patron of the Arts

Oxford himself was a patron of the arts who loved theatre and poetry and commissioned various books and translations. Twenty-eight books were dedicated to him during his life. Oxford sponsored two theatre troupes: a men’s troupe and a boys’ troupe. He leased the Blackfriars Theatre in the 1580s for his boys’ troupe.

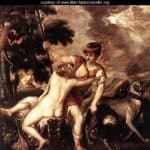

#4. Titian’s Adonis with Hat

The long narrative poem, Venus and Adonis, the first work published under the name William Shakespeare, describes Adonis wearing a “bonnet.” This mirrors one of the many paintings of Venus and Adonis by the Venetian artist, Titian – the only one that shows Adonis wearing a bonnet. This could only have been seen at Titian’s studio in Venice, a city where Oxford spent a great deal of time during his mid-twenties.

#5. Ovid’s Metamorphoses

Ovid’s Metamorphoses, which is recognized as one of Shakespeare’s most influential sources, second only to the Bible, was translated into English by Arthur Golding, Oxford’s uncle. Oxford and Golding were living in the same household when the translation was being completed.

#6. “To Be or Not to Be”

The famous “To be or not to be” soliloquy in Hamlet echoes Gerolamo Cardano’s Comforte (De Consolatione), written in 1542: “What should we account of death to be resembled to anything better than a sleep. . . . We are assured not only to sleep, but also to die.” Oxford commissioned an English translation of Cardano’s Comforte by Thomas Bedingfield (1573) for which Oxford wrote the preface.

#7. “Polonius,” AKA Sir William Cecil, Lord Burghley

Polonius in Hamlet has long been recognized as a parody of Sir William Cecil, Lord Burghley. Oxford had a long and often uneasy relationship with Burghley, who was first, his guardian, then later his father-in-law. Polonius’ advice to his son Laertes in Hamlet echoes a list of maxims that Burghley posted for the benefit of his household. The list was never made public until after Hamlet was published. In Hamlet, Polonius sends a servant to spy on his son when he is away at university, just as Burghley did with his son. Burghley sponsored Parliamentary legislation that made Wednesdays “fish-days,” a fact that may have inspired Shakespeare to have Hamlet call Polonius a “fishmonger.” Burghley’s motto was “Cor unum, via una” (“One heart, one way”). In the First Quarto of Hamlet, the Polonius character is named “Corambis,” (“double-hearted”), a parody of Burghley’s motto. Hamlet was not published until after Burghley died, as Oxford had no need to provoke his father-in-law while he lived.

#8. Young Men Falling Out at Tennis

Polonius’ mention of young men “falling out at tennis” in Hamlet refers to a famous incident in which Oxford had a quarrel on a tennis court with Sir Philip Sidney in 1579. Oxford and Sidney were rivals in many ways. Both had sought the hand of Burghley’s daughter Anne; they also disagreed on politics and literature. Sidney was playing tennis with some friends when Oxford came along and asked if he could join in. Sidney simply ignored him. In the ensuing quarrel, Oxford called Sidney a “puppy.” Oxford would later parody Sidney as Sir Andrew Aguecheek in Twelfth Night, Slender in Merry Wives, and the Dauphin in Henry V, who says that his horse is his mistress (Sidney wrote a sonnet to his horse).

#9. Captured by Pirates!

One of the plot twists in Hamlet finds Hamlet being captured by pirates on his way to England and being left naked on the shore of Denmark. Oxford was returning to England from the continent when he was captured by pirates who left him naked on the shore of England.

#10. The “Fair Youth”

Henry Wriothesley, the Third Earl of Southampton, was a beautiful young nobleman to whom Shakespeare expressly dedicated the two narrative poems Venus and Adonis and Rape of Lucrece. Many scholars believe that Southampton was also the “Fair Youth” of Shakespeare’s Sonnets. Around the time that the Sonnets are thought to have been written, Lord Burghley was trying to persuade a reluctant Southampton to marry Oxford’s daughter Elizabeth, who was also, of course, Burghley’s granddaughter. In the first 17 sonnets, the poet encourages the Fair Youth to marry and procreate. It would have been entirely presumptuous for William Shakspere, a commoner, to write sonnets offering marital advice to a young nobleman. The Sonnets make much more sense if they are seen as coming from an older nobleman to a younger one whom the older nobleman hopes will become his son-in-law.

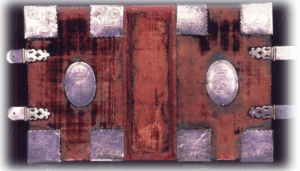

#11. Oxford’s Geneva Bible

Oxford’s handwritten notations in his personal copy of the Geneva Bible show a strong correlation to biblical references in Shakespeare’s works, as Professor Roger Stritmatter demonstrated in his Ph.D. dissertation at the University of Massachusetts. The more often a biblical passage is referenced in Shakespeare’s works, the more likely it is to have been marked in Oxford’s Bible.

#12. Dividing the Kingdom

Oxford had three daughters, just as King Lear did. And just as Lear divided his kingdom among his daughters while he still lived, Oxford placed his family lands in trust for the benefit of his daughters while he lived.

#13. 3,000 Ducats

In The Merchant of Venice, Antonio, the merchant, borrows 3,000 ducats from Shylock, the moneylender, to help finance Bassanio’s wooing of Portia. In real life, Oxford borrowed 3,000 pounds from a moneylender named Michael Lok, to finance a voyage seeking a northwest passage to India. The character Shylock greatly resembles Gaspar Ribeiro, a Venetian Jew who was successfully sued for making a usurious 3,000-ducat loan. Ribeiro lived in the same parish in Venice where Oxford attended church.

#14. Baptista and Spinola

Shakespeare’s Taming of the Shrew features a rich man named Baptista Minola, who is the father of two daughters eligible for marriage, Kate and Bianca. In Italy, Oxford borrowed money from a man named Baptista Nigrone and also from a man named Pasquale Spinola, whose names must have inspired Minola’s name.

#15. That Rare Italian Master, Julio Romano

In The Winter’s Tale, a statue of the queen is described as “a piece many years in doing and now newly performed by that rare Italian master, Julio Romano . . . .” Romano is the only artist mentioned by name in Shakespeare’s works. Many critics have scoffed at Shakespeare’s ignorance in thinking that Romano was a sculptor when he was actually a painter. But Shakespeare was right and the critics were wrong. Romano was a sculptor as well as a painter, as witnessed by his sculpture on the tomb of Baldassare Castiglione in Mantua. Castiglione, by the way, was one of Oxford’s heroes and Oxford commissioned the translation of Castiglione’s Book of the Courtier into Latin so that noblemen all over Europe could benefit from it. Mantua is along the route Oxford is known to have traveled, and he would likely have wanted to pay his respects there to one of his spiritual mentors.

#16. Romano’s Room

Speaking of Julio Romano, also in Mantua are Romano’s paintings of the Trojan War on the walls and ceiling of the Sala di Troia (“Room of Troy”) in the Palazzo Ducale (ducal palace). In Shakespeare’s narrative poem, The Rape of Lucrece, the heroine, after she has been raped, goes into a room with paintings on the walls depicting the Trojan War. The descriptions of those paintings, which encompass over 200 lines, bear striking resemblances to the paintings in the Sala di Troia.

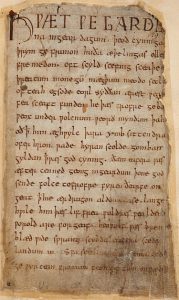

#17. Hamlet and Beowulf

Shakespeare’s Hamlet gets much of its plot from versions of an old tale as told by the Dane Saxo Grammaticus and the Frenchman François de Belleforest. Neither of these stories, however, contains anything like the scene where Shakespeare’s dying Hamlet turns to his friend Horatio and implores him:

Horatio, I am dead;

Thou livest; report me and my cause aright

To the unsatisfied.

. . .

O good Horatio, what a wounded name,

Things standing thus unknown, shall live behind me!

If thou didst ever hold me in thy heart

Absent thee from felicity awhile,

And in this harsh world draw thy breath in pain,

To tell my story.

This part of the story may have been inspired by the ending of the Old English epic poem Beowulf, the first known work of literature in the English language. When the hero Beowulf is dying from wounds inflicted on him during a battle with a dragon, he turns to his fellow warrior, Wiglaf, and asks him to create a burial mound in his memory:

The battle-famed bid ye to build them a grave-hill . . .

As a memory-mark to the men I have governed,

Aloft it shall tower . . .

That earls of the ocean hereafter may call it

Beowulf’s barrow.

Thus, both Hamlet and Beowulf use their dying breaths to ask that they be remembered. In Oxford’s time, however, Beowulf could not be bought from a bookseller, nor borrowed from a library. In fact, there was only one copy of it in existence, in manuscript form. That copy was owned by a man named Laurence Nowell. And who was Laurence Nowell? One of Oxford’s tutors.

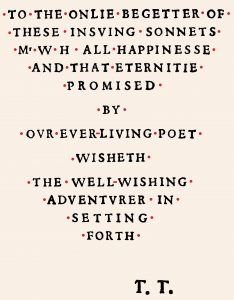

#18. “Our Ever-Living Poet”

Shakespeare’s Sonnets were first published in 1609. There are indications on the dedication page that the author was no longer living at that time. First, the dedication is signed by the publisher, Thomas Thorpe, not by the author, suggesting that the author was not alive to write the dedication. More significantly, the dedication refers to the author as “ever-living.” This is a phrase that was used metaphorically to refer to a person who was no longer alive, but who would live on through his works in our minds and hearts. The Earl of Oxford was no longer living in 1609, while the man from Stratford, who is usually credited with writing the works of Shakespeare, would live on for another seven years. Stratfordian scholars have never been able to explain why the phrase “ever-living” would have been applied to a living person.

LEARN MORE

FURTHER READING

The above are just a few of the many connections between Oxford’s life and the works of Shakespeare. You can learn more at the following links:

See the SOF Shakespeare Authorship 101 page for a concise overview of reasons to doubt that William Shakspere of Stratford-upon-Avon wrote any of the plays or poems in the first place.

See also the in-depth review of The Case for Oxford by historian Ramon Jiménez.

Poetic Justice for the True Shakespeare? (introducing major new studies of parallels between Oxford’s early poetry and private letters and numerous works in the Shakespeare canon)

Ten Clues to the Identity of Edward de Vere as “William Shakespeare” (about 1,300 words)

Why Would Anyone Need to Fake Shakespeare’s Authorship? (about 3,000 words)

Hamlet as Autobiography: An Oxfordian Analysis by Felicia Londré (about 4,800 words)

The Case for Oxford Revisited by Ramon Jiménez (about 8,500 words)

“Shakespeare” Identified in Edward De Vere, the Seventeenth Earl of Oxford by J. Thomas Looney (original public domain text as published in London in 1920) (click here for the reasonably priced modern scholarly edition of this classic masterpiece of literary detective work)

ABOUT THE AUTHOR

Tom Regnier (1950–2020) earned his J.D. summa cum laude in 2003 at the University of Miami School of Law, where he taught “Shakespeare and the Law” for many years as an adjunct professor. He earned his LL.M. in 2009 at Columbia Law School, where he was a Harlan F. Stone Scholar. He also taught at Chicago’s John Marshall Law School. He became a prolific independent Shakespearean scholar, combining his interests in Shakespeare and the law. He served as President of the SOF (2014–18) and was honored as Oxfordian of the Year in 2016. You can read here about his final public lecture, on the centennial of the Oxfordian theory, with links to his obituary, his major writings and speeches, and much additional information.