Who Wrote Shakespeare? Shakespeare Authorship 101

Shakespeare, among all great writers in world history, presents a unique mystery. Despite centuries of efforts to resolve doubts that the author was the businessman and actor from Stratford-upon-Avon, questions about the authorship persist. Who really wrote the works of “William Shakespeare”?

12 Reasons to Question Who Wrote Shakespeare

#1. Where’s the paper trail?

Despite hundreds of years of exhaustive research, no one has found a single letter written by Shakspere to anyone (in most surviving personal records, that or some variation is how his name is spelled — not “Shakespeare” or “Shake-speare,” the almost uniform spelling in the published works). Nor has anyone found any book Shakspere owned, any letter to him from any other known literary figure, nor any record of patronage or payment for writing.

In short, no one during his lifetime clearly recognized him, personally, as a writer. But don’t take our word for that: Sir Stanley Wells, distinguished scholar and staunch defender of the traditional view, has candidly conceded this point (“Allusions” in Edmondson & Wells, 2013, p. 81). And this is not typical of that era, even for much more obscure authors. A thorough survey of two dozen other English writers of the time found all had more documentation of their literary careers — often much more. A leading scholar confessed “despair” at the “vertiginous” gap between the works and the historical records of the supposed author.

#2. Why the gap in historical records?

During Shakspere’s lifetime, references to the author “Shakespeare” are basically impersonal. Some don’t even use the name, but just allude cryptically to works like Venus and Adonis. Many references imply “Shakespeare” is a pen name — that the author is hidden in some way (see #6 on early doubts). By contrast, the documents we have relating personally to Shakspere of Stratford reveal mundane business activities, money-lending, and lawsuits — but never hint at any literary career. No matter how much defenders of the traditional Stratfordian theory try to rationalize away this problem, it remains a bizarre mystery.

Again, don’t take our word for it: The great Shakespearean scholar Samuel Schoenbaum (staunch Stratfordian) confessed his “despair of ever bridging the vertiginous expanse between the sublimity of the subject and the mundane inconsequence of the documentary record” (Shakespeare’s Lives, 1991, p. 568).

#3. Why only cryptic posthumous hints?

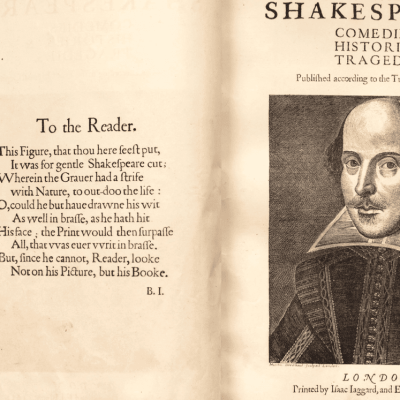

The first suggestions linking the author to Stratford-upon-Avon were published seven years after Shakspere’s death in the 1623 First Folio. The Folio, and the monument in Stratford’s Holy Trinity Church, are both full of puzzling oddities raising questions about the author’s identity. Ben Jonson wrote two prefatory poems in the Folio (one shown above), both laced with riddles. Orthodox scholars have noted for 250 years that Jonson probably ghostwrote other parts of the Folio preface, making attributions to “Heminges” and “Condell” doubtful at best. A leading biographer calls Jonson an “exceedingly disingenuous” writer (Riggs, 1989, p. 225). Can we trust anything the Folio says?

#4. Why did family and friends never suggest he was a writer?

At least ten eyewitnesses who knew Shakspere or his family, and who left behind significant writings, never mentioned he was a writer.

Shakspere’s son-in-law, Dr. John Hall, kept a journal in which he wrote of the “excellent poet” and Warwickshire native Michael Drayton. But Hall, among at least ten eyewitnesses with personal knowledge of Shakspere or his family, and who left behind significant writings, never mentioned that Shakspere himself was a writer (much less the greatest of the age). There’s no evidence that Shakspere or any member of his family, even decades after he died, ever claimed he was the author of the works of “Shakespeare” — or had any literary career at all!

People often cite Ben Jonson, whose actual relationship with Shakspere is unclear. But there’s no record of Jonson ever suggesting Shakspere was a writer during Shakspere’s lifetime — nor in 1616 after he died, when Jonson published a folio with epigrams addressed to half a dozen writers and to actor Edward Alleyn. Jonson merely listed “Shakespeare” twice (hyphenated once) as a cast member in Jonson’s plays.

#5. Why the complete silence when he died?

In an age of copious eulogies, the reaction to Shakspere’s death in 1616 was eerie silence. Jonson’s non-reaction (see #4) is the strangest example. Compare the flood of grief and eulogies for Shakspere’s fellow actor Richard Burbage, said to eclipse the mourning for Queen Anne when she and Burbage died in 1619. Yet we’re supposed to believe this same Shakspere was really the “Star of Poets” and “Soul of the Age” hailed by Jonson (belatedly) in the 1623 Folio? Several references before 1616 suggest the real author died years earlier (see #6 and #12). And what about Shakspere’s own deafening silence in 1612 on the death of Prince Henry, the heir to the throne? See discussion below about Edward de Vere (Oxford) (Point #10).

#6. Why did Shakespeare authorship doubts arise so early?

Authorship doubts arose more than 30 years before the First Folio. Dozens of writings raising questions about the author’s identity were published for decades before Shakspere’s death in 1616. The authorship question thus did not first arise (as often falsely claimed) in the 19th century. The authorship debate began right away when these works were first published. Several publications before 1616, especially the Sonnets (see #12), suggest the author “Shakespeare” (whoever that really was) died years earlier.

References to the author during this time were impersonal, veiled, or cryptic (see #2 and #3). Some suggested “Shakespeare” was a pseudonym and that a frontman was involved. The title of a 1611 epigram did so openly and with startling bluntness: addressing “Shake-speare” as “our English Terence.” Terence was an ancient Roman playwright notorious as a suspected frontman for two hidden, aristocratic writers.

#7. Will’s will: another shoe that doesn’t fit?

Shakspere’s will, despite its detailed disposal of household items, makes no mention of books (not even a family Bible), manuscripts, desks, musical instruments, or anything suggesting literary, artistic, or intellectual interest. He cruelly disinherited his wife of more than 30 years, leaving her only his “second-best bed,” at odds with the theme of remorse and reconciliation with women in many Shakespeare plays.

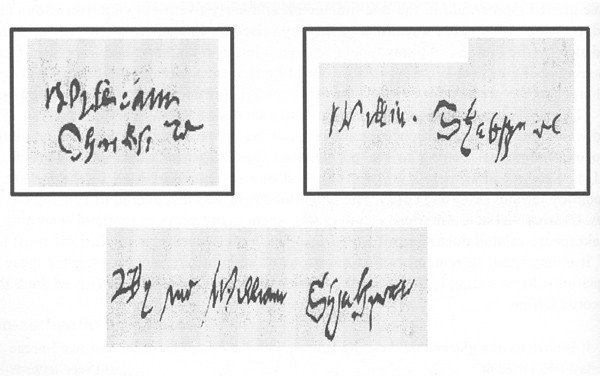

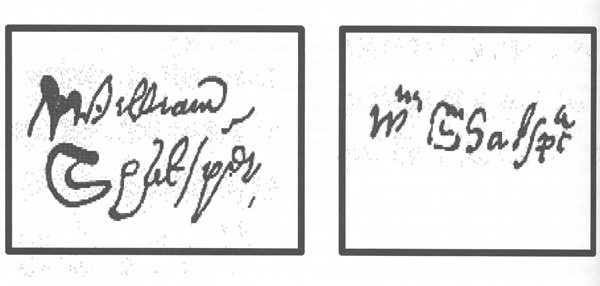

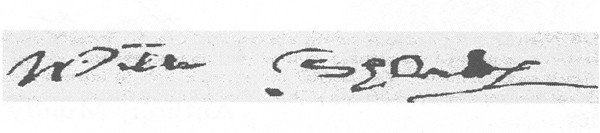

#8. The “Star of Poets” could barely sign his own name?

The only accepted specimens of Shakspere’s handwriting are six tortured, almost illegible signatures. An expert with no stake in the authorship dispute has declared they were written by different people. Some may have been signed on his behalf. Read more about how scholars have interpreted these clumsy markings and take a look for yourself:

#9. The creator of Portia failed to educate his own daughters?

Shakspere did not bother to educate his daughters. Like his parents, they were apparently illiterate — in stark contrast to the highly educated young women in many Shakespeare plays, including Portia in The Merchant of Venice; Miranda, tutored by her father Prospero in The Tempest; and Helena, whose learning and skill as a healer save the king’s life in All’s Well That Ends Well.

#10. How did Shakespeare get away with satirizing Queen Elizabeth and her top officials?

At a time when other authors (including Ben Jonson) were called before the Star Chamber, imprisoned, tortured, or even executed for writings deemed offensive, how did the commoner Shakspere prosper with no penalty? The queen’s top minister, Sir William Cecil (Lord Burghley), perhaps the most powerful man in England, is parodied in Hamlet as Polonius (“Corambis” in the 1603 quarto — an obvious pun on Burghley’s motto). When Cecil died in 1598, his son Sir Robert inherited his power. Sir Christopher Hatton is mercilessly satirized as Malvolio in Twelfth Night (Olivia seems to represent the queen). The farcical romance in A Midsummer Night’s Dream, between Titania and donkey-headed Bottom, seems to mock the queen’s courtship by the French duc d’Alençon.

#11. How can we explain the total mismatch between the works and the alleged author?

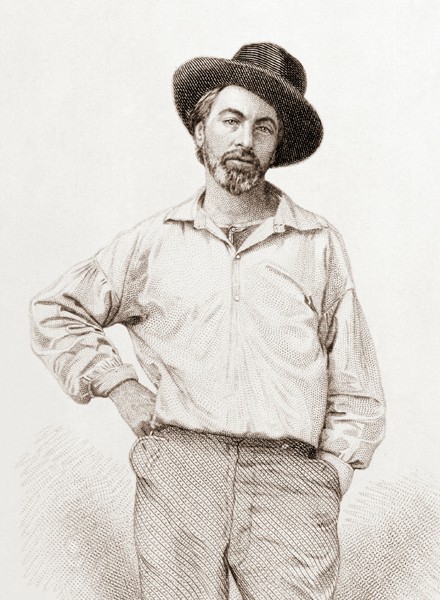

The documented life of Shakspere of Stratford is jarringly inconsistent with the plays and poems of Shakespeare. The Stratford man was a middle-class social climber, yet the works express contempt for the attitudes necessary for success in his social milieu. They reflect, instead, an unmistakably aristocratic viewpoint, as Walt Whitman recognized (November Boughs, 1888, p. 52), inferring that “only one of the ‘wolfish earls’ so plenteous in the plays themselves” would “seem to be the true author.”

The author Shakespeare was deeply familiar with law — making accurate use of arcane legal terms and resorting to legal metaphors as if by natural habit — and with many other fields of knowledge including music, foreign languages, medicine, military and nautical affairs, and aristocratic sports like falconry. The works rely on myriad classical and Renaissance sources in French, Italian, Spanish, Latin, and Greek, some not yet translated into English at the time. The plays and poems reveal extensive foreign travel, including intimate familiarity with the art, culture, and geography of Italy.

It’s difficult to imagine how Shakspere of Stratford could have gained such experience or knowledge or access to the rare and expensive books required. There’s no evidence he ever traveled outside England (extremely expensive and politically risky at the time), or had any chance to obtain higher education. Rudimentary Latin was taught at the Stratford Grammar School (attendance records are lost), but not any other foreign languages.

#12. The Sonnets: heart of the mystery?

The dedication of the Sonnets in 1609 described the author as “our ever-living poet.” Standard sources like the Oxford English Dictionary confirm that “ever-living” was used to indicate a deceased person, immortal in a religious or figurative sense. Shakespeare’s Henry VI Part 1 refers to the deceased King Henry V as “that ever-living man of memory.” But Shakspere lived until 1616! (See also #6 on early doubts.) The poet says his name will be buried forever (see Sonnets 72 and 81) — but “Shake-speare” was part of the title and plastered all over numerous plays as well!

Scholars, both skeptical and orthodox, have explored many divergent theories about the Sonnets (the SOF takes no official position), but virtually everything about them clashes with the man from Stratford.

Many scholars interpret the Sonnets, along with various Shakespeare plays, to suggest the author’s romantic or sexual interest in men as well as women. This would have been deeply scandalous, even dangerous, for Shakspere of Stratford if he were writing under his own name (sex between men was a death-penalty offense then). He married his lifelong wife in his teens after impregnating her. Sonnets believed to be written in the early 1590s depict a lame author in his 40s who has suffered some disgrace. Shakspere was then in his late 20s, on the verge (so we’re told) of a bright and successful career.

So Who Wrote Shakespeare?

Meet Edward de Vere (Oxford), the real Shakespeare

Edward de Vere, 17th Earl of Oxford, was a patron of literature, music, and theatrical players, hailed by other writers of his time as a fine playwright and poet. He was at the center of Elizabethan literary life, acquainted with key personalities depicted in the works of “Shakespeare.”

The following summary barely covers the highlights of the case for Edward de Vere, 17th Earl of Oxford, as the true author “Shakespeare.” Oxford’s life, private letters, early known poetry, and verses marked in his personal Bible contain hundreds of parallels to the Shakespearean plays and poems. No wonder so many writers, thinkers, artists, and public figures have embraced the Oxfordian theory. Consider ten key points:

#1. Connections to Shakespeare’s Sonnets

The Sonnets cannot plausibly be squared with Shakspere of Stratford (see Reason to Doubt #12), but they fit perfectly with Oxford. He may well have been bisexual; he was accused of same-sex liaisons. Unlike Shakspere, Oxford might actually have “bor[n]e the canopy” over the queen to which Sonnet 125 alludes. The poet refers several times to his lameness. Oxford was lame because of an injury in the 1580s; he complains about it in his letters.

Oxford, like the author of the Sonnets, was plagued by scandals and disgraces. Still more circumstances, including Oxford’s 40+ age when the Sonnets were written starting in the early 1590s, and his death in 1604, fit with their contents and apparently posthumous publication, hiding a deceased but “ever-living” author.

#2. Elizabethan Pen Names and Frontmen

During this era a powerful stigma attached to publication and other professional activities by aristocrats, especially plays produced for the public stage. The taboo was occasionally violated, and evolved over time, but as late as the Caroline court (1625–49), William Selden wrote that it was “ridiculous for a Lord to print Verses; ’tis well enough to make them to please himself, but to make them public is foolish.”

Fear of scandal could also explain why Oxford, specifically, chose or perhaps was required to use a pseudonym — and why his and other families may have insisted on its maintenance long after his death. Venus and Adonis (1593) and The Rape of Lucrece (1594), the first published works to bear the name “William Shakespeare,” were both dedicated to Henry Wriothesley, Third Earl of Southampton, with whom unsuccessful discussions were held about a marriage to one of Oxford’s daughters. Southampton may well have been recognizable as the “fair youth” of the Sonnets (as he’s still widely viewed to this day) — depicted in a scandalous bisexual love triangle with the author and the Dark Lady.

It was common during this era to use pseudonyms, anonymity, and other veiled forms of writing, due to the stigma of print and because publishing controversial material was dangerous. Elizabethan England was a police state in which arbitrary arrest, censorship, torture, and the death penalty were routine. The use of frontmen was a well-known strategy, judging by Queen Elizabeth’s reaction to a provocative 1599 book about the deposed King Richard II. The book was by historian John Hayward, but the queen thought he was “pretending to be the author in order to shield ‘some more mischievous’ person, and … should be racked so that he might disclose the truth” (Dictionary of National Biography, 1891, v. 25, p. 311).

#3. A Discreet Writer Praised by Contemporaries

Oxford was hailed in general terms as a fine poet and playwright, among the “best for comedy,” as Francis Meres described him in 1598. The Arte of English Poesie (1589), the leading work of literary criticism of the Elizabethan era, cited Oxford as “first” among courtiers “who have written excellently well, as it would appear if their doings could be found out and made public with the rest.”

These and other contemporaries who praised him did not link him to any specific plays, thus respecting his own discretion to that extent. Many plays at this time were performed privately at the royal court or aristocratic homes. Orthodox scholars increasingly accept the idea that many “Shakespeare” plays were first performed in such locations.

Only a few early poems that Oxford wrote as a boy or young man have come down to us linked explicitly to his name or initials. Private circulation and occasional publication of poetry, strictly as a pastime, was apparently acceptable. But we have no plays at all explicitly linked to Oxford. This could well be explained by another passage in The Arte of English Poesie, stating that “very many” courtiers “suppressed” what they wrote “or else suffered it to be published without their own names to it.”

#4. Oxford as Spear-Shaker

For a controversial author-courtier such as Oxford, writing scandalous satires for the public stage, a pseudonym would have been essential. The dashing and vivid pen name “William Shakespeare” (often hyphenated “Shake-speare”) could hardly be more fitting. It may have invoked Athena (Pallas or Minerva), the Greco-Roman goddess of wisdom and patron of Athens (home of Greek theatre) — also viewed during the Renaissance as a patron of the arts. According to legend, she came into the world brandishing a spear and is often depicted that way. She was specifically associated in Renaissance Europe with the action of spear-shaking.

Oxford was known at court as a champion jouster — literally a spear-shaker. Gabriel Harvey delivered a Latin address to Oxford in 1578, a passage in which translates as “thy countenance (or glance) shakes spears.”

#5. Connections to Nobility and Royalty

The Shakespeare plays and poems reveal an author deeply influenced by specific works of literature (Ovid’s Metamorphoses, for example) — and acquainted with prominent persons and events of Queen Elizabeth’s court — as to which we know Oxford also had intimate connections and knowledge. The multiple links between Oxford, Shakespearean poems, and the Earl of Southampton are mentioned above.

As noted in Reason to Doubt #10, Sir William Cecil (Lord Burghley) is satirized in Hamlet as Polonius. When Oxford’s father died, the 12-year-old earl became a royal ward in Cecil’s custody. Cecil later became his father-in-law. Sir Christopher Hatton, mocked as Malvolio in Twelfth Night, was one of Oxford’s enemies at court and a competitor for the attention of the queen. The poem employed to entrap Malvolio into his fantasy that Olivia loves him, “The Fortunate Unhappy,” inverts Hatton’s motto, Foelix Infortunatus (“happy, though unfortunate”). Perhaps only a high-ranking aristocrat like Oxford, viewed with lenient affection by the queen, could have gotten away with such portrayals — especially the scandalous mockery in A Midsummer Night’s Dream of her courtship by a French nobleman! Hamlet bears remarkable similarities to Oxford’s life. Among many other points: Like Hamlet, he was abducted by pirates while sailing for England.

#6. More Connections, Especially to Hamlet

The works of Shakespeare contain remarkable parallels to events and relationships in Oxford’s life. He is easily recognizable in the guise of various characters, including Romeo, Bertram in All’s Well That Ends Well, Berowne in Love’s Labour’s Lost, and above all, Hamlet. Oxford, just like Hamlet, was even abducted by pirates while sailing for England and “set naked” on the shore.

Oxford’s prefatory letter in Thomas Bedingfield’s translation of Cardanus Comforte (1573), which was published at Oxford’s urging, is strikingly Shakespearean in character. Orthodox scholars have found such intimate linkages between this treatise and Hamlet that they refer to it as “Hamlet’s book” (yet they ignore the connections to Oxford). Oxford’s mother, like Hamlet’s, remarried soon after his father’s death. Oxford married Cecil’s daughter Anne, just as Hamlet loved Ophelia, daughter of Polonius. Cecil’s documented private precepts, created for his son, show up as fatherly advice by Polonius to his son Laertes.

#7. Italian Connections

Oxford spent a year traveling in continental Europe, especially Italy, visiting the very cities (like Venice and Verona) that feature most compellingly in Shakespeare plays. There’s no evidence that Shakspere of Stratford ever left England. Oxford, not Shakspere, had the opportunity to acquire the intimate knowledge of Italian language, art, theatre, culture, and geography that permeates so many Shakespearean works.

#8. Connections to the First Folio

The 1623 Folio was dedicated to Oxford’s son-in-law Philip Herbert, Earl of Montgomery, and to Philip’s brother William Herbert, Earl of Pembroke (Lord Chamberlain in charge of theatres), who at one time was sought as husband to another of Oxford’s daughters. The Folio was an expensive and risky publication, probably subsidized by these powerful and wealthy patrons (as noted under Reason to Doubt #3, it’s riddled with cryptic hints that something’s fishy about its authorship).

#9. Stratfordian Mismatches Fit Perfectly With Oxford

See Reason to Doubt #11 (mismatches with Shakspere of Stratford). Knowledge of law? Check: Oxford studied law at Gray’s Inn and had to be conversant as a member of the House of Lords and judge in major state trials. Military and nautical knowledge? Check: He participated in military campaigns and traveled by sea.

Foreign travel? Languages? Elite education? Knowledge of the classics? Music? Medicine? Aristocratic attitudes, sports, and pastimes? Insider knowledge of court politics?

Check, check, check, check … it goes on and on.

No one’s ever found a book belonging to Shakspere or any evidence he owned one (see Reasons to Doubt #1 and #7). But the Folger Shakespeare Library has a very important book owned by Oxford — a Geneva Bible — with many marked verses linking intriguingly to biblical references pervading the works of Shakespeare. After Oxford died in 1604, King James had eight Shakespeare plays produced at court: a tribute to the true Bard?

#10. 1604: Not a “Problem” — Timing Supports Oxford and Refutes the Stratfordian Theory

Events after 1604 lend still more support to the Oxfordian theory. The First Folio’s letter to readers says the author was “by death” deprived of the chance “to have set forth, and overseen his own writings.” That’s puzzling for Shakspere of Stratford, who enjoyed years of retirement, but fits perfectly with Oxford’s death in 1604 at the height of the publication and performance of many of Shakespeare’s greatest plays.

Despite frequent claims to the contrary, no Shakespearean work has ever been proved to be written after 1604 (see FAQ #4 on this page, upper right). Both Stratfordian and Oxfordian theories depend on the idea that many plays were first published years after they were written, even after both purported authors died. Both theories accept the possibility of co-authorship and posthumous revision.

In late 1604, King James had eight Shakespeare plays produced at court, perhaps a tribute to Oxford. James patronized Shakspere’s theatre company, the King’s Men. Yet stunningly, when his beloved teenage son Prince Henry died in 1612, causing a paroxysm of national grief, King’s Man Shakspere was … coldly silent?

You can sample some of the outpouring of mediocre verse mourning Prince Henry in this 1870 book, The Courtly Poets, from Raleigh to Montrose (pp. 183–85). Ask yourself: Couldn’t the author of The Phoenix and the Turtle have done a lot better? Then ask: Why didn’t he?

There’s a pretty simple and obvious answer: “Shakespeare” the actual author was dead by then. When the Sonnets were published in 1609, the dedication referred to the poet as “ever-living,” a term only applied to the dead (see Reason to Doubt #12). It could not possibly refer to Shakspere, who lived until 1616, but yet again fits perfectly with Oxford.

The foregoing are among several indications that the author “Shakespeare” died years before. It’s actually Shakspere of Stratford (not Oxford) who is confounded by 1604 (and 1616) “problems.”

Scholars generally agree the Sonnets were completed by 1604. No references to later events have been found in them. Sonnet 107 alludes to the 1603 death of Queen Elizabeth and the poet states that “death to me subscribes” as well. Oxford died a year later.

In Sum: Stratford's the Problem — Oxford's the Solution

The theory that Shakspere was the author generates endless and puzzling questions. At every turn, the Oxfordian theory provides logical, common-sense answers and clarity.

The lack of explicit “smoking gun” evidence for either Shakspere or Oxford (or any other authorship candidate) is certainly frustrating: It’s why people are still debating this question hundreds of years later.

But the Oxfordian hypothesis explains much better the evidence we have. It rests on solid evidence, mainly circumstantial — which any good lawyer, detective, or scientist will tell you is often the best and most reliable kind. Since the modern proposal of the theory in 1920, it has been confirmed and corroborated by more and more newly discovered and newly analyzed evidence (just some of it summarized here) — the surefire sign that a theory is on the right track.

To explore it further, check out this helpful overview. See also the FAQs and links at the upper right of this page. They lead to a vast trove of scholarly books, articles, and sources documenting all these points, discussed throughout this website.

Who Really Wrote Shakespeare?

FAQs

Why do people doubt the traditional story about Shakespeare?

The reasons for doubt are many and varied. They spring largely from the mismatch between the life of the alleged author and the character of the literary works attributed to him.

The traditional view requires a suspension of disbelief which a growing number of scholars are unable to accept as rational. As W.H. Furness (the 19th-century clergyman, abolitionist, and father of Shakespearean scholar H.H. Furness) once said: “I am one of the many who has never been able to bring the life of William Shakespeare within planetary space of the plays. Are there any two things in the world more incongruous?”

Such doubts have been echoed by numerous perceptive readers, including Walt Whitman, Henry James, Helen Keller, Sigmund Freud, and Orson Welles, just to mention a few. See many more on our page devoted to “Famous Shakespeare Authorship Skeptics.”

Why should we care who wrote the works of "Shakespeare"? Isn't it enough that we have them?

First of all, the topic has obvious and profound historical interest.

As the scholar Katherine Chiljan has stated: “If the true biography of one of the greatest minds of Western civilization does not matter, then whose does?” Doesn’t it matter that for hundreds of years, students have been taught (as an unquestioned truth) a point of view which now seems, to a growing number of scholars, highly doubtful at best?

Second, the claim that “we have the works” is itself very dubious given the persistent and profound doubts about the true author.

If literary biography is an essential tool to provide insight into any text, then attaching the wrong author’s name to the works leads to a host of false assumptions, which may spawn serious misconceptions about them.

The authorship question is thus not merely a matter of honoring the true author, though that alone is an important ethical obligation for any serious reader. It is also about better understanding the works of “Shakespeare” that so many of us love, study, and enjoy.

How could Oxford be the author if he died in 1604, before some Shakespearen works are said to have been written?

Aren't the Oxfordians just snobs who think only an aristocrat could have written great literature?

No. This accusation is a tiresome old chestnut. The charge of “snobbery” or class bias is a lazy cheap shot designed to shut down rational discussion and replace logic with emotion.

If anything, there is a greater potential for bias in the strong ideological or emotional preference that many Stratfordians seem to have for an author of modest social origins.

Authorship doubters have never questioned that people of modest origins can become great writers (as many obviously have). The issue is not who could have written the works of Shakespeare in the abstract, but which specific person most likely did write the works.

Even highly imaginative authors tend to write in a way that reflects their real-life experiences and social background, including class, gender, religion, and race. This is an obvious and commonplace insight, generally accepted by orthodox scholars themselves in almost every literary context other than Shakespearean studies. Why would the author “Shakespeare” (whoever that was) be some kind of peculiar exception?

Innumerable aspects of the Shakespeare canon, noted by perceptive critics like Walt Whitman (a great artist who himself came from very modest origins), suggest an author of aristocratic background and bias (not to mention privileged opportunities including superb education and extensive travel).

The perspectives and experiences of the author “Shakespeare” seem to have been quite different in various ways compared to his brilliant contemporaries Ben Jonson or Christopher Marlowe, who both arose from even more modest origins than Shakspere of Stratford.

It is not “snobbery” to recognize all this, but fact-based realism.

The snobbery slander is merely one more indication that many defenders of the traditional authorship theory are deeply afraid to confront and fairly debate the relevant facts.

Aren't the Oxfordians just conspiracy theorists with too much time on their hands?

How can I learn more?

Explore this website! And check out the latest Shakespeare authorship discoveries in our publications: The Shakespeare Oxford Newsletter, The Oxfordian, and Brief Chronicles (both our scholarly journal published 2009–16, and our book series.