The Snobbery Slander

The Most Ironic and Outrageous Attacks on Oxfordians and Other Authorship Doubters

by Bryan H. Wildenthal

July 15, 2019

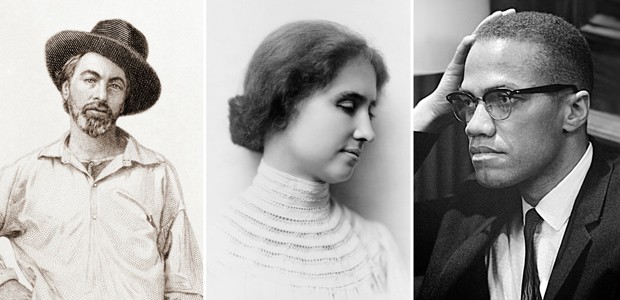

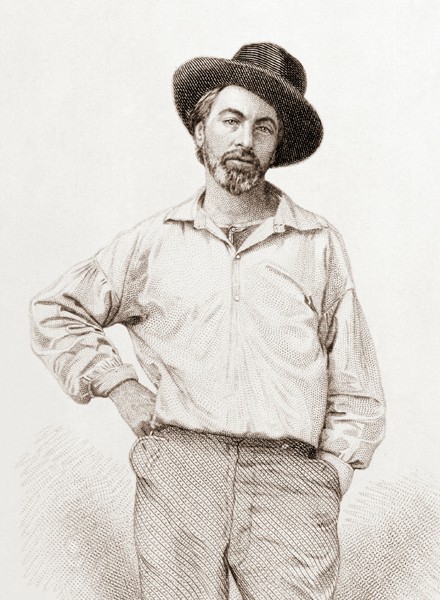

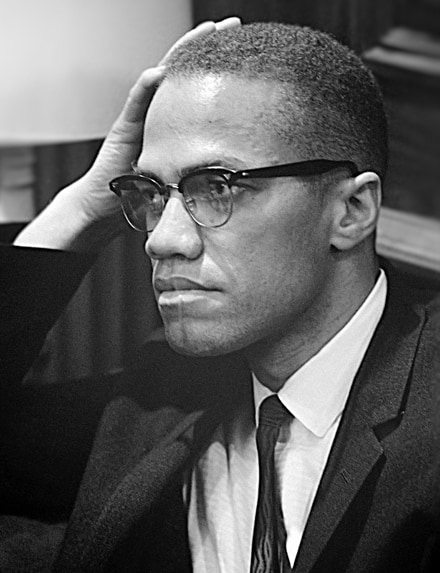

Walt Whitman, Helen Keller, Malcolm X: Can the sheer absurdity of the snobbery slander aimed at authorship doubters be dramatized better than by this simple triptych? Such doubts are one of the few things uniting these three strikingly diverse Americans — that and their shared passion for human dignity and democracy.

This essay explores various slanderous attacks commonly aimed at those who doubt the traditional view of Shakespeare authorship — especially at Oxfordians. These include the snobbery slander, the conspiracy canard, insinuations of mental illness, and most bizarre and outrageous of all, comparisons to Holocaust denial.

Understanding these feverish attacks requires thoughtful consideration of why many people are so deeply attached to the traditional (“Stratfordian”) authorship story in the first place. Upon careful examination, these attacks are not just baseless distractions but deeply ironic as well. They reveal far more about Stratfordians than they do about doubters.

The Emotional and Ideological Appeal of the Traditional Story

William Shakspere of Stratford-upon-Avon (1564–1616), the provincial commoner who supposedly became the author “Shakespeare,” the jewel in the crown of English literature, is an icon revered as Britain’s national poet. It is not only Britons who feel an emotional connection to that author (whoever it was). I do myself, like so many others. It sometimes seems like Americans and people of many nationalities around the globe are equally or even more obsessed with Shakespeare than the British.

For many Britons, his identity — quite understandably — is a matter of patriotism and intense national pride. Most are deeply committed to the traditional belief that Shakspere of Stratford was the true author of the Shakespeare canon. So are most Americans and others around the world. (On why it is both convenient and justified to spell the Stratford man’s name as “Shakspere,” see Wildenthal, “Reflections on Spelling,” and Wildenthal 2019, 41–52.)

You mess with their small-town hero at your peril. Mark Anderson, in his 2005 biography of Oxford (411), recalled “encounters with otherwise reasonable people who became irrational and red-faced with anger when the words ‘earl of Oxford’ were uttered.” He noted that the Shakespeare Authorship Question (SAQ) is “considered a heresy in the church of English letters.”

Many Stratfordians view the traditional theory of Shakespeare authorship as inerrant gospel truth — an infallible and unquestionable premise. Many do not take kindly to those who question it. To do so, in their eyes (as Anderson found), is not merely foolish but heresy. Many object especially to any suggestion that the true author was an aristocrat. This seems to cause many to express particular ire toward Oxfordians, who believe the evidence indicates the true author behind the “Shakespeare” pseudonym was Edward de Vere, 17th Earl of Oxford (1550–1604).

The Snobbery Slander: A Tiresome Old Chestnut

The claim that many or most authorship doubters (especially Oxfordians) are just “snobs” is a tiresome old chestnut, a classic ad hominem cheap shot. It is grossly inaccurate and unfair to the overwhelming majority of Oxfordians and other doubters, past and present. But it is also deeply revealing and merits careful examination. Class-based feelings do indeed play a role in the SAQ, but not in the way traditionalists think.

It is possible that some people have been drawn to Oxford or other authorship candidates by some sort of elitist preference. But a theory is not disproven just because some may embrace it for the wrong reasons. Charles Darwin’s insights into biological evolution, for example, cannot rationally be rejected simply because they became entangled (and remain so to some extent) in spurious associations with rightwing and often racist “social Darwinist” ideas.

The obvious ideological and emotional appeal of the Stratfordian story — a poet who rose from the common people in a small provincial town to take London by storm and become England’s greatest writer — is similarly not a valid basis for any views about authorship, one way or the other. Either preference could, in principle, become a source of bias.

Even some Stratfordian scholars have admitted that this has, in fact, generated troubling distortions in orthodox scholarship. Professor Lukas Erne observed, in his landmark 1998 article, “Biography and Mythography,” that “it seems impossible to approach [Shakespeare’s] life from a neutral and disinterested point of view” (439). Quoting another orthodox scholar, Erne noted the constant pressure to interpret and embellish the known facts with “guesswork, legend and sentiment” (439 & nn. 34, 37, quoting Dutton, 1–2; internal quotation marks omitted).

Scholars in glass houses should not throw stones. Sauce for the goose is sauce for the gander.

There are ample grounds for the late U.S. Supreme Court Justice Antonin Scalia’s suggestion that Stratfordians may be “more … affected by a democratic bias than the Oxfordians are … by an aristocratic bias.” Yet Scalia’s own wife reportedly needled him with the old snobbery chestnut, charging that Oxfordians just “can’t believe that a commoner” wrote the works of Shakespeare (Bravin; Wildenthal, “Oxfordian Era”).

Very revealing is a statement by Sir Jonathan Bate: “I actually think it’s terrific that someone from an ordinary background can get to be a great writer, just as it’s terrific that someone from an ordinary background can get to be president of the United States.” (Wilson & Wilson, Last Will. & Testament, 2012, minute 2.)

Was Bate perhaps projecting the mirror image of his own bias when he accused Alexander Waugh of embracing the Oxfordian theory in part because Waugh and other members of his family allegedly “love an aristocrat”? (Waugh & Bate 2017, minute 18; Bate also referred to Oxfordians, at minute 17, as “cultists.”) Waugh, a successful author in his own right, is the grandson of Evelyn Waugh (1903–66) (author of the beloved classic Brideshead Revisited and other novels), and son of Auberon Waugh (1939–2001) (a prominent writer and columnist). With this smoothly vicious comment, Bate managed to unite the snobbery slander with a charge of inherited guilt by association.

Apparently, as Bate commented during that 2017 debate, he and Waugh are personal friends, surprising as that seems. Let me note that I myself have great respect for Bate’s scholarship and insights. Oxfordians would do well to read his work carefully. Some of it, though surely inadvertently, supports authorship doubts (see Wildenthal 2019, 181–84, 190–91), even as Bate indulges in laughably extreme denialism about the reality of early doubts during Shakespeare’s own lifetime (quoted in Wildenthal 2019, 39–40). For a thorough critique of Bate’s debacle of a performance in the 2017 debate, see Steven Steinburg’s brilliant 2018 essay.

A Glance at the Conspiracy Canard

Scott McCrea, a leading Stratfordian, wrote a book on the authorship question in 2005 with a chapter entitled “All Conspiracy Theories Are Alike” (ch. 15, 215–23). No, they’re not all alike. And the SAQ cannot rationally be dismissed as “just a conspiracy theory” in any event.

The conspiracy canard is not the most offensive taunt aimed at doubters. History testifies that conspiracies do happen sometimes. Some important (even sensational) secrets have been kept for long periods of time. The possibility of some kind of conspiracy playing some role in the SAQ should not be ridiculed or dismissed. People during Shakespeare’s time may have been reluctant for various reasons to speak, write, or record for posterity whatever they knew about the authorship issue (if they even cared, which most probably did not). England in those days was a highly repressive police state in which arbitrary arrest, censorship, torture, and the death penalty were routine.

But authorship doubts do not depend, in any event, on any strong notion of conspiracy. There’s no need to imagine any impossibly vast yet tightly controlled plot. The truth may well have been an open secret, the “Shakespeare” pseudonym a polite public fiction — possibly well-known to some, suspected by others, and a matter of indifference to most.

The many early doubts published about Shakespeare’s authorship demonstrate that whatever conspiracy, deception, or secrecy was attempted was actually not that successful — not even during his own time! My 2019 book explores those early doubts and questions at great length.

The conspiracy taunt is also hypocritical, since many Stratfordians concede and even contend for the existence of long-hidden authors and co-authors of numerous works published as by “Shakespeare.” Traditionalists and doubters generally agree that the author Shakespeare (whoever that was) did not write many of the poems published in The Passionate Pilgrim (1599) or the plays Locrine (1595), Thomas Lord Cromwell (1602), The London Prodigal (1605), or A Yorkshire Tragedy (1608) — all published under his name or initials.

The editors of the new Oxford University Press edition of the Shakespearean works have claimed (based on dubious “stylometric” analysis) that up to one third of the entire canon was co-authored by as many as ten writers other than Shakspere of Stratford — including Christopher Marlowe! The editors dismiss anti-Stratfordian doubts about the primary author as “unscholarly,” but they do not explain how their alleged “co-authors” somehow remained hidden, unknown, and uncredited until modern times. (You can read here an excellent review of the OUP edition by Dudley, Goldstein & Maycock; for more on “stylometric” analysis generally, click here.)

What vast “conspiracy theory” could possibly explain how all those alleged ghostwriters were somehow kept secret all these centuries? Once again, sauce for the goose is sauce for the gander. (See Wildenthal 2019, 57–59, citing, e.g., Dudley, Goldstein & Maycock.)

It took 200 years for the truth about President Thomas Jefferson’s likely sexual relationship with his slave Sally Hemings to be revealed. Until recently, virtually all mainstream historians scornfully rejected that as a fringe theory. It took a full century for anyone to dare state in print that Sir Philip Sidney’s Astrophel and Stella sonnets (published in 1591) were actually inspired by his infatuation with Lady Penelope Rich. Not until 1935 did most literary scholars finally accept that likelihood.

Truths may often remain hidden for a long time. (For more discussion and rebuttal of the conspiracy canard, see, e.g., Price, 224–33; Wildenthal 2019, 323–30.)

The Snobbery Slander: A Hip Makeover?

Sir Jonathan Bate notwithstanding, most orthodox scholars are now too polite (or too politic) to sling the snobbery slander around as freely as it used to be. At least one staunchly Stratfordian scholar, Professor Steven May, who has produced valuable studies of Oxford’s known early poetry (cited extensively in “Twenty Poems,” 2018), has more reasonably conceded that Oxfordians have “made worthwhile contributions to our understanding of the Elizabethan age” and “are educated men and women … sincerely interested in Renaissance English culture,” whose “arguments … are entertained as at least plausible by hosts of intellectually respectable persons” (May 1980, 10; see also Twenty Poems of Edward de Vere: Overview).

Professor James Marino of Cleveland State University, however, has vigorously promoted the snobbery slander in recent years. Marino has published brilliant and valuable Shakespearean scholarship (e.g., Owning William Shakespeare, a 2011 book I highly recommend), some of it implicitly supporting authorship doubts (as with Bate, surely inadvertently; see Wildenthal 2019, 61–62).

Marino has tried to give the snobbery slander a hip contemporary makeover, linking it to the struggle against income inequality. “Occupy Wall Street” meets the Bard? I’ve not yet met or conversed with him, but I bet he’s a nice guy. Apparently we have a friend in common, another professor I know at Cleveland State. I suspect I and other Oxfordians might enjoy sitting around with Marino over coffee or beer, to chat informally about our shared love for this author and these plays and poems. There’s a lot we could learn from each other.

Yet Marino, some years ago (Dagblog, Nov. 3, 2011) — writing, ironically, under his own thinly veiled pseudonym — asserted that Oxfordians “desire to claim that Shakespeare was in the 1%. Only an aristocrat, the conspiracy theorists say … on top of the social and economic pyramid, could have created such art. The stakes here,” he suggested, involve some kind of plot to claim the works of Shakespeare as “the property of the inherited elite.”

Wow, talk about a “conspiracy theory”!

Marino continued: “The Oxfordian argument is … [a] crazier version of a process … in which the small elite of the super-wealthy are given credit for the achievements of the rest of society.” Writing under his own name (Penn Press Log, Nov. 1, 2011; see also Dagblog, Dec. 31, 2014, revealing his authorship), Marino also accused Oxfordians of “a deep-seated need to believe that Shakespeare was an aristocrat.”

Marino’s screeds are entertaining, to be sure. They are also caricatures utterly detached from reality. Has he ever met a real Oxfordian? As an Oxfordian myself, who has gotten to know many others quite well, I speak from direct personal knowledge. Quite irrelevant is my personal sympathy for Marino’s left-leaning concerns about economic inequality. But I do not think my own political or economic views have any rational bearing on who wrote the patently aristocratic-leaning works of Shakespeare, a point Marino should pause to consider.

Yet Marino, thou art more temperate compared to Amanda Marcotte, a political blogger who described authorship doubts (Rawstory, 2014) as “Shakespeare trutherism” motivated by “unsavory classism,” which she ranted is “quite a bit like Obama birtherism.” (How could anyone have missed that?) Marcotte asserted that both “serve [a] belief that the person in question, by virtue of his supposedly low birth, does not deserve his fame and authority,” and that both allegedly “express unsavory ideas — that black men cannot be Presidents, [and] common men cannot be great poets.”

Marino’s 2014 Dagblog post linked approvingly to Marcotte’s, calling it a “smart takedown” of authorship doubts. So perhaps he’s not more temperate (sigh). I note wearily the irrelevant fact that former President Obama enjoys many impassioned (now very nostalgic) supporters (including me) among Oxfordians.

Oxfordians and Other Skeptics: An Ideological Rainbow Coalition

Not that it should matter, but Oxfordians — and authorship doubters in general — encompass a vast and diverse range of political and social views: Republicans, Democrats, independents, libertarians, socialists, devout religious believers, atheists, you name it. I find it refreshing how the SAQ brings together so many thoughtful people of good will across such divisions, united by our love of Shakespeare and our fascination with the history of that era.

The Democrat who sought to succeed Obama, former U.S. Senator and Secretary of State Hillary Rodham Clinton, appears to be an authorship doubter herself. Asked by the New York Times Book Review in 2014 which three writers in history she would invite to a dinner party, Clinton said just one: “William Shakespeare. I’m curious to see who would show up and what he really wrote.”

Helen Keller

Keller, another prominent American woman (well to the left of Clinton), expressed authorship doubts more than a century earlier.

Deafblind from infancy, Keller inspired millions with her courageous brilliance as a writer and lecturer. She identified as a socialist and was a fierce advocate for civil rights, workers’ rights, and women’s voting rights.

The Perkins School for the Blind, which Keller attended, celebrates to this day her defiant embrace of Shakespeare authorship doubts. Keller loved the works of Shakespeare. But when she insisted on continuing to write about authorship doubts (including a manuscript rejected by numerous publishers), she encountered the patronizing dismissal and scorn that so many doubters have.

“I do wish editors and friends could realize that I have a mind of my own,” she protested (Winter).

Justices Scalia and Stevens — and the Entire Ideological Spectrum of the Supreme Court

The late Justice Antonin Scalia, the leading conservative voice for many years on the U.S. Supreme Court (appointed by Republican President Ronald Reagan), was an Oxfordian, just like his long-serving colleague widely viewed as a leader of the Court’s liberals, the late Justice John Paul Stevens (though appointed by Republican President Gerald Ford). The late Justice Harry Blackmun, another liberal (though appointed by Republican President Richard Nixon), was also an Oxfordian.

Two centrist “swing voters” on the Supreme Court, the late Justice Lewis Powell (another Nixon appointee) and the retired Justice Sandra Day O’Connor (another Reagan appointee), round out the ranks of known authorship doubters on the Court during the past half-century. The late Justice Ruth Bader Ginsburg (appointed by Democratic President Bill Clinton), a progressive champion who succeeded Justice Stevens as leader of the Court’s liberals, also expressed some interest in the SAQ. Perhaps she was influenced by her friend Scalia. (See Wildenthal, “Oxfordian Era”; Regnier; Foggatt.)

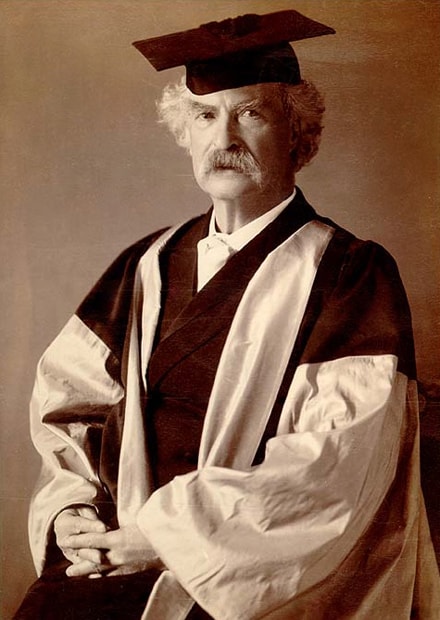

Mark Twain

Amanda Marcotte conceded “surprise” that Twain, perhaps America’s most beloved writer of all time, scathingly rejected the Stratfordian authorship theory. But that barely slowed her down from falsely dismissing his views as dating only from “his cranky old rich man years” (Rawstory, 2014). Actually, as she could have learned with a modicum of research before spewing venom on the internet, Twain’s fascination with the SAQ dates to his youth as an apprentice boat pilot on the Mississippi River. He noted “my fifty years’ interest in” the issue near the beginning of his easily available book on the subject (1909, 4) — which, typically for Twain, is highly entertaining. Marcotte might enjoy it.

Walt Whitman

Would Marcotte diss Whitman with a similar ad hominem smear? Hailed by many as the greatest poet in American history, Whitman arose from a famously modest social background. A passionate tribune of democracy and the common man, he actually expressed distaste for Shakespeare’s own elitist attitudes.

Yet Whitman, as noted earlier, foreshadowed the Oxfordian theory. He suggested, in reference to the English history plays (1888, 52), that “only one of the ‘wolfish earls’ so plenteous in the plays themselves, or some born descendant and knower, might seem to be the true author of those amazing works.” But I guess Marcotte would still backhand him as being, by 1888, just another “cranky old rich man.”

What about Helen Keller? What does Marcotte think about her authorship doubts? Oxfordians, I suppose, should feel honored to be lumped together with some of America’s finest writers as objects of this sort of mindless bile.

Malcolm X

Given Marcotte’s playing of the race card as mentioned above (linking doubters to anti-Obama “birthers” and those who think “black men cannot be Presidents”), one wonders what she would make of the fact that Malcolm X was an authorship doubter.

Just another snob? Malcolm, during his famous self-education in prison, began to think the true “Shakespeare,” based on the evidence of the works, must be not merely aristocratic, but royal. He speculated that the true author might have been King James I.

Unlike Marino and Marcotte, Malcolm was able to separate his own normative ideological views from evidentiary questions of literary history. He obviously did not favor aristocrats or royalty. He thought the King James Bible had “enslaved the world.” (Malcolm X, Autobiography, 185; see generally ch. 11.)

An Unhinged Pièce de Resistance

It’s hard to choose, but perhaps the most unhinged expression of the snobbery slander is Ron Rosenbaum’s 2011 essay, with a title that pretty much says it all: “10 Things I Hate About Anonymous and the Stupid Shakespearean Birther Cult Behind It.”

Rosenbaum, an otherwise rational and respected journalist and author, allowed that “Oxfordianism is not exactly the literary equivalent of Holocaust denial,” but he declared: “I really hate what these people do, the Oxfordians. Their titanic smugness, their snobbishness. … Most of all, I hate the way they pride themselves on the vain, mendacious conceit that they’re in on a grand historical secret deception that only they have the superior intelligence to understand.” (Slate, 2011; first emphasis added; second emphasis, on “hate,” is in the original.)

Oh my. And to think we doubters are often told we are too humorless and weirdly obsessed? Can we all just relax, get along, and debate this issue in a friendly and constructive way?

Memo to the hyperventilating Rosenbaum: Yes, Oxfordians do think we have figured out the real author, not because we claim any special “intelligence” but because the circumstantial evidence is quite compelling. You might try reading up on it (see, e.g., Jiménez). Honestly, we’re not snobs and we certainly don’t “hate” anyone over this issue. Awfully sorry you do. We just want to explore a fascinating historical mystery. Is that really so bad?

Replacing One Alleged Prejudice With Another? Why Can’t a Great Writer Be an Aristocrat?

Bate, Marino, Marcotte, Rosenbaum, and others notwithstanding, I have never met a single Oxfordian, or any Shakespeare authorship doubter, who would not cheerfully agree that many common men (and women) have become great writers. Christopher Marlowe, Shakespeare’s contemporary, is just one example.

Some Stratfordians may have a hard time wrapping their heads around it, but quite a few Oxfordians (like me) are distinctly left-liberal in our politics. As much as we love the works of Shakespeare and admire whoever wrote them, many of us (like Whitman) are actually troubled by the degree to which they are pervaded by aristocratic prejudice — among other biases. But then, life and art are often messy and do not conform to prim and pristine notions of virtue. Great artists are not always the most morally admirable people, nor (necessarily) the kind you’d want to date, to marry, or to babysit your kids.

To recognize Oxford as the likely author behind the “Shakespeare” pseudonym is not something most of us “desire.” It’s a matter of facing up to reality based on compelling circumstantial evidence. Personally, I would rather find evidence that Marlowe was the true author, gay commoner and atheist rebel that he was by some accounts.

Certainly no one could accuse Marlovians of snobbery! He came from a more modest background than Shakspere, who after all was a product of the upper middle class and died quite wealthy. Whatever my personal biases, however, the weight of the evidence points me to Oxford.

The real question is why so many Stratfordians insist on irrationally denying the possibility that this author was, indeed, an aristocrat. Why is that so difficult to accept? One of the greatest writers in Russian (or world) history, Count Leo Tolstoy, was an aristocrat. So was Lord Byron. There are many more examples of great writers from aristocratic or privileged backgrounds. Such backgrounds, quite obviously (however unfairly), often provide more opportunities for raw talents to blossom and be nurtured. Why not “Shakespeare” too?

The fact that many people seem to have a deep-rooted emotional and ideological preference or desire for “Shakespeare” to be a common man is no excuse for ignoring what the evidence tells us. Open your eyes and take an honest look at Shakespeare’s own writings!

An Ironic Reality Check: The Aristocratic Bias of the Shakespearean Works

As Joseph Sobran pointed out in his insightful 1997 book, it is “strange that an author whose biases are so obviously aristocratic” (13), indeed, whose “philosophy is thoroughly feudal” (169), has become “an icon and test of democratic faith” (13). That’s a pretty big irony — on top of the irony, discussed above, that many Stratfordians accuse doubters of being biased by snobbery when in fact they seem far more biased by their own preference for a humble author.

Given the tendency of some Stratfordians to go ad hominem, it seems best to preemptively concede here that Sobran (1946–2010) was, in my view, a troubling personality on multiple counts, a prominent rightwing columnist whose views on some issues, anathema to mine to begin with, became more reckless and extreme with time (see, e.g., Grimes). But his 1997 book on the SAQ is deeply thoughtful and gracefully written. There seems no basis to link his views or writings on the SAQ with any of his unrelated ideological views (see, e.g., Wildenthal 2019, 337 n. 38).

Sobran grasped the nettle that many Stratfordians seem to find too painful: This author has “little interest in the sort of self-made man his [Stratfordian] champions suppose him to have been” (13). Sobran did not contend, nor would I, that the author lacks all empathy for commoners (see Sobran, 164; Wildenthal 2019, 338 n. 42). But to the extent he shows interest in them, it is most often to ridicule their speech, which he treats as a class trait (see Sobran, 164–65, and generally 163–72). As Sobran perceptively noted (165), such mockery of speech patterns is a classic marker of stereotyping against “those we perceive as ‘others’.”

Shakspere was an ambitious commoner, as reflected in his quest for a coat-of-arms. The author Shakespeare seems to view such people across a wide and deep class divide. Yet the author portrays members of the social elite as nuanced individuals — “because he is one of them,” Sobran suggested (165). Sobran documented the author’s “habitual language [in] the idiom of the courtier,” matching that to Oxford’s surviving letters (170; see generally 167–72).

Judging from the works, this author seems not to have the smug bourgeois attitudes of a commercially successful middle-class arriviste, but rather exactly the kind of tortured ambivalence and preoccupations one might expect to find in a decadent, disgraced, and disillusioned aristocrat.

It is not snobbery but simply realistic to observe that the works of Shakespeare “suggest an author of privileged background — one who not only received the best education available, but who also knew court life, traveled widely, and enjoyed other advantages beyond the reach of a man of rustic origins, however intelligent” (Sobran, 9). Nor is it snobbery to admit the glaringly obvious mismatch between the known facts of Shakspere’s life and the content and ambience of the Shakespeare canon (see, e.g., Jiménez).

No one doubts that artists of modest origins may achieve supreme artistry. Many have. But the issue is what sort of art any given genius may create. As Sobran noted (9): “A Streetcar Named Desire may not be as great a play as Hamlet, but the author of Hamlet couldn’t have written it and Tennessee Williams could. This is a matter not of genius but of individuality.”

Amateur Armchair Psychoanalysis?

We should hesitate to psychoanalyze Stratfordians as they so freely indulge in psychoanalyzing doubters. But one has to wonder about the fervor and even fury with which some of them fling the snobbery charge, and recoil from the evidence pointing to the real author. Might this be, for some, a way of projecting (unconsciously?) their own discomfort and dissonant feelings about the painfully obvious class and other biases in these works we all love so much? It almost seems like an effort to cancel that out by building up the author, however implausibly, as some kind of working-class hero — a role for which Shakspere of Stratford was never well-cast in any event.

Like so many Shakespeare lovers past and present, Stratfordian and skeptical alike, I veer close to “idolatry” of this writer. Whatever privileges he inherited, whatever personal demons possessed him, he was a supremely gifted artist with profound psychological insight — brilliantly perceptive, capable of transcending himself and empathizing with a stunning range of characters, and self-aware enough to grasp the cruel random truths and ironies of his unjust society and his own place in it.

But no one who truly loves Shakespeare, who respects the depth and complexity of this artist and his work, should flinch from confronting his many disturbing facets. I suspect the author wrestles with his own conscience when he has Queen Gertrude beg Hamlet (act 3, sc. 4): “[S]peak no more. Thou turnst mine eyes into my very soul, And there I see such black and grained spots As will not leave their tinct.”

In a pervasively racist and anti-Semitic era, this author dared to depict a dark-skinned hero in Othello (flawed but noble personally, not by birth or title), who defiantly marries a privileged white woman (the ultimate taboo), portraying their passionate love with heartrending authenticity. Yet he embraced racist and anti-Semitic stereotypes readily enough on other occasions, as in Titus Andronicus (Aaron), The Tempest (Caliban), and most infamously The Merchant of Venice, where yet he could not resist turning Shylock into a compellingly memorable character.

One hesitates even to broach the author’s wildly conflicted attitudes toward women, veering from comedic (satirical?) celebrations of patriarchy (e.g., The Taming of the Shrew), to the bitter venting of misogyny (e.g., Hamlet), to his uncannily sympathetic portrayals of many richly imagined female characters (in works as diverse as The Rape of Lucrece, Much Ado About Nothing, and The Winter’s Tale, to suggest just a few examples).

Many Stratfordians seem to want to celebrate a more politically correct and palatable author — good sweet Will, man of the people, hale fellow well met. But in doing so, they take the easy way out.

For far too long when it comes to the SAQ, orthodox academics, whatever their motives, have largely avoided the simple duty that any serious scholar has: to engage forthrightly with the evidence. Such scholars, when they deign to mention the SAQ at all, have focused almost entirely on trying to denigrate or psychoanalyze authorship doubters.

In its most insulting and ridiculous forms, this amateur psychoanalysis has involved suggestions, not just of snobbery, but of outright mental illness and even, as by Rosenbaum above, comparisons to Holocaust denial. (See, e.g., Wildenthal, “Rollett and Shapiro”; Shahan, SAC Letters, 2010–15; Edmondson & Wells 2011.)

Samuel Schoenbaum, one of the most respected Shakespeare scholars of the 20th century, penned the classic attack on the mental stability of doubters (440, quoted in Sobran, 13). Schoenbaum asserted “a pattern of psychopathology … paranoid structures of thought … hallucinatory phenomena” and “descent, in a few cases, into actual madness.” He argued that such “manifestations of the uneasy psyche” indicate a need “not so much for the expertise of the literary historian as for the insight of the psychiatrist. Dr. Freud beckons us.” Indeed!

This began a chapter in which Schoenbaum (440-44) patronizingly purported to psychoanalyze Sigmund Freud’s own Oxfordian persuasion. Was Schoenbaum suggesting the great psychoanalyst was himself just another nutcase? No, just that “psychoanalytic theory explain[s] the unconscious origins of anti-Stratfordian polemics” (444).

Really? If only someone could figure out what might explain the unhinged polemics of many Stratfordians. I have offered above my own tentative and amateur suggestion.

More recently, Sir Stanley Wells penned an absurd attack on skeptics — laughable, were it not so outrageously offensive — posted on the Shakespeare Birthplace Trust and then Royal Shakespeare Company websites. Wells, indulging in still more amateur psychoanalysis, ascribed the SAQ not just to “snobbery” but also to “desire for publicity; and even … certifiable madness.” Years of protests by John Shahan’s Shakespeare Authorship Coalition eventually persuaded the SBT and then the RSC to take it down (Shahan, SAC Letters, 2010–15).

The Outrageous Comparison to Holocaust Denial

My 2016 essay, “Rollett and Shapiro,” discussed the comparisons of the SAQ to Holocaust denial by Professor Stephen Greenblatt of Harvard University, in 2005, and Professor Gary Taylor of Florida State University, in 2014 (see Reisz). That comparison and the other slanders discussed here are repeated ad nauseum online by internet trolls. Leading academics do set a tone.

Professor James Shapiro of Columbia University has claimed to eschew Holocaust denial comparisons to the SAQ as a “mistake” (2010, 8). Yet he also could not really resist. He piously disclaimed any intention of “draw[ing] a naive comparison between the Shakespeare controversy” and various “other issues” — among which he listed Holocaust denial — “except insofar as [the SAQ] too turns on underlying assumptions and notions of evidence that cannot be reconciled” (2010, 8; my emphases). So he actually was invoking a Holocaust denial comparison — just not (so he claimed) a “naive” one. His was more subtle, more cleverly cloaked in plausible deniability.

Professor Shapiro is a brilliant writer and his scholarly work commands respect. I own and admire several of his books. Like so many of us, he obviously loves Shakespeare (the author, whoever that was). But Shapiro’s treatment of the SAQ has been consistently tendentious, misleading, and littered with misstatements of fact. And he knows better. Given Shapiro’s expertise and knowledge of the overall subject, it must regrettably be stated that his approach to the SAQ shows every evidence of misguided fervor and intellectual dishonesty. Mistakenly equating the SAQ with genuinely far-fetched “conspiracy theories,” Shapiro has embarked on a crusade against authorship doubters, losing sight in the process of whatever scholarly perspective he may once have had. (See, e.g., Hope, “Is That True?” (reviewing Shapiro’s 2010 book, Contested Will ); Wildenthal, “Rollett and Shapiro”; Wildenthal 2019, 7–12, 22, 34–37, 44–45, 157–59, 342–46 (and sources cited therein); see also, e.g., Anderson, Waugh & McNeil, debunking numerous errors in Shapiro’s 2015 book, The Year of Lear.)

Scott McCrea also invoked the Holocaust denial comparison (2005, 216), though like Shapiro he was hesitant, conceding that “obviously [the SAQ] lacks the same moral dimension.” Yes, “obviously”! So why not refrain from drawing the comparison altogether?

The Holocaust denial comparison was recently invoked by Oliver Kamm, a columnist at the Times of London and leading British journalist. In the online journal Quillette (May 2019), Kamm lobbed a furious attack on Elizabeth Winkler’s thoughtful recent essay in The Atlantic exploring the SAQ in relation to Emilia Bassano Lanier, an intriguing woman of the English renaissance. Winkler’s sin in Kamm’s eyes? She conceded and discussed the obvious existence of reasonable doubts about the Stratfordian theory of Shakespeare authorship.

Kamm’s essay, a nasty brew of falsehoods, misleading statements, and ad hominem attacks, dismissed the SAQ as “an entirely worthless conspiracy theory.” He eagerly embraced the Holocaust denial comparison, quoting McCrea. Kamm conceded that authorship doubters “may find this an outrageous and even inflammatory analogy, but they should consider it carefully.”

Oxfordians and other skeptics do find the Holocaust denial comparison “outrageous” and “inflammatory” — because it is. Please stop it. It is Kamm who failed egregiously to “consider it carefully” and who plainly needs to do so. Kamm echoed the snobbery slander too, ascribing the SAQ to “the Victorian sense of propriety and order,” supposedly “offended” by the “notion that a commoner lacking a university education could have written the greatest literary works in the language.”

Kamm’s essay noted that he is a friend of Professor Shapiro, who cited Kamm’s essay in Shapiro’s own error-strewn attack on Winkler’s essay, sadly published by The Atlantic itself. Shapiro’s essay falsely denied the existence of any early doubts about Shakespeare authorship (but see generally Wildenthal 2019, especially 34–37). Shapiro wrongly labeled as a “falsehood” Winkler’s accurate acknowledgment of such doubts.

Shapiro spewed repetitive epithets against doubters: “fantasists,” “peddle[rs] [of] fiction,” inhabitants of “an alternate universe,” “conspiracy theorists,” “fringe movement,” et cetera ad nauseum. Name-calling, of course, is the well-known resort of those whose rational arguments, based on relevant facts, are less than convincing.

Shapiro refrained from explicitly repeating Kamm’s comparison to Holocaust denial. And he only hinted at the snobbery slander, suggesting that people “have doubted Shakespeare’s authorship” only because he “was an actor and a moneylender, a profile that doesn’t match what we like to think a real writer should be! It turns out that it’s possible to lend money and act and still write great plays.” But that’s a red herring, not denied by skeptics and totally irrelevant to the primary grounds for authorship doubt.

The message sent by Shapiro’s approving linkage to Kamm’s essay was clear enough. He specifically cited Kamm for the point that “journalists … have a special obligation to steer clear of promoting conspiracy theories,” thereby falsely associating Winkler and the SAQ with the entire range of such “conspiracy theories” discussed by Kamm (which, as noted, included Holocaust denial).

Shapiro himself, echoing Amanda Marcotte (discussed above), explicitly compared Winkler and other authorship skeptics to anti-Obama “birther” conspiracists and “anti-vaxxers.”

Shapiro’s attack on Winkler is no surprise in hindsight, given his similar attack shortly afterward in The New Yorker on the late Justice John Paul Stevens, who (as noted above) was an Oxfordian. Stevens was also one of the most admired judges ever to grace the bench of the U.S. Supreme Court, on which he served for 35 years. Shapiro described and quoted from a series of letters he exchanged with Stevens in 2011–12.

Shapiro pretended to show respect for Justice Stevens, accurately noting that it “say[s] a lot about this extraordinary man” that he “would engage so generously with a fellow-citizen [he] never met.” But Shapiro repaid that generosity by slandering the recently deceased Stevens just when he was unable to defend himself. Shapiro smeared him as a conspiracy theorist, outrageously likening his authorship views to “anti-vaxxer propaganda” and “belief that the moon landing was faked.”

Shapiro’s Atlantic essay lectured Winkler — the concept of “mansplaining” comes to mind — that she would be well advised to give up what he derided as her “fantasies” about authorship. Instead, he patronizingly urged, she should redirect “her attention [to] those heroines whose words resonate powerfully for her.” One suspects Winkler is not in need of Shapiro’s arrogant guidance about the proper limits of her intellectual inquiries. He would do better to emulate Winkler’s spirit of inquiry and revisit his own dogmatic adherence to unquestioned Stratfordian assumptions.

While posturing as sympathetic to Winkler’s exploration of depictions of women by Shakespeare and the insights of “a half century of feminist scholarship,” Shapiro made the astonishingly distorted and misleading claim that it is “clear that there was no stigma attached to a woman writing or publishing a play” during the Elizabethan era. His only supporting citation was to the first and famously rare example of an early modern English woman publishing a play, in 1613 (ten years after the death of Queen Elizabeth), that was never performed at the time to anyone’s knowledge. He omitted the latter fact. And Shapiro calls authorship doubters “denialists”?

Does it not occur to all these orthodox critics of the SAQ just how arrogant, reckless, and harmful the Holocaust denial comparisons are? Leave aside how nasty and unwarranted in this context. Little wonder that arguments about the SAQ have so often, so sadly, become so strangely and needlessly bitter, given such outrageous overkill.

Does it not occur to these scholars — some of them leading professors who really should know better — how much the comparison insults and disrespects the victims of the Holocaust, by associating Holocaust denial with a legitimate debate about literary history? Does it not occur to them that this enhances the credibility of those who deny or question the reality of the Holocaust, by linking them to those with incomparably more reasonable, well-founded, and morally responsible questions about Shakespeare authorship?

Is it even minimally responsible or reasonable (let alone “naive”) to compare extensively documented events within living memory — and uncountable thousands of contemporaneous, detailed, written and oral testimonials — with far more obscure and murky aspects of 16th and 17th century literary history, as to which all witnesses died hundreds of years ago, surviving documentation is scarce, and what there is, difficult to interpret?

As legitimate and worthwhile as the SAQ is, no one (including authorship doubters) would suggest it ranks with anti-Semitic violence in historical importance. So the invocation of the latter, in this context, functions as a grotesquely heavy-handed cheap shot. The comparison weaponizes a false association with a real and deadly form of bigotry, in the context of what would otherwise be a harmless and enjoyable (if rarefied) academic parlor debate.

We get that orthodox scholars find the SAQ annoying. But have they lost all sense of proportion and decency in deploying this kind of nuclear response?

As unfair as the Holocaust denial comparison is to those who seek to honestly explore the SAQ, the far worse effect is to risk trivializing the horrific historical reality of anti-Jewish bigotry. It is difficult to overstate the offensive cynicism of this strategy. It is disgusting. It is insulting to the millions who have suffered from anti-Semitic violence.

Holocaust denial is a disturbing subject meriting careful study. I can hardly do it justice here, nor can this essay effectively explore the broader problem of irrational denialism. The literature on Holocaust denial is vast. Excellent overviews of the subject are provided in Professor Deborah Lipstadt’s indispensable book and Michael Shermer’s broader exploration of irrational belief systems (ch. 13, 188–210).

The broader phenomena of irrational denialism and far-fetched conspiracy theories do offer cautionary lessons that authorship doubters should always keep in mind. Any skeptic venturing to question a dominant mainstream view should, of course, do so in a rational, thoughtful, and responsible way.

But those who forswear or demonize any questioning of the conventional view on Shakespeare authorship make the kind of mistake the late Carl Sagan warned us against (though I am not aware of any views he had on the SAQ). Sagan, the great scientist, humanist, and exponent of rational inquiry, cautioned us to always maintain “an exquisite balance between two conflicting needs: the most skeptical scrutiny of all hypotheses that are served up to us and at the same time a great openness to new ideas.” As Sagan noted: “If you are only skeptical, then no new ideas make it through to you. You never learn anything new.” (Sagan, “The Burden of Skepticism,” 1987, quoted in Shermer, opposite table of contents.)

Anyone who seriously studies and compares Holocaust denial and the SAQ will be struck far more by their profound differences, not similarities. Doubts about Shakespeare’s authorship go back to when the works were first published (see generally Wildenthal 2019). Modern authorship doubters, for more than 150 years, have included thousands of distinguished scholars, judges, writers, and artists, and innumerable highly educated, thoughtful, well-informed, and decent people (including many Jews, by the way, not least Sigmund Freud as mentioned above) — some of whom lost family members or other loved ones to the Holocaust (see, e.g., Reisz, quoting Richard Waugaman).

We do not deserve to be linked to Holocaust deniers. More importantly, they do not deserve to be linked to us.

A Milder Form of Bullying?

The milder version of orthodox denigration — almost more maddeningly smug and condescending — has been to retreat behind a fog of fashionable academic jargon, analyzing authorship doubt as a purely contingent product of time and culture. Typical examples of the latter are Shapiro’s 2010 book and many of the essays in the 2013 Edmondson & Wells anthology.

Shapiro spoke at length about the SAQ in a December 2016 interview with Brooke Gladstone on the public radio show On the Media. Shapiro’s opinions came as no surprise, but one might have hoped Gladstone, a respected journalist, would try to be more fair. Sadly, while Gladstone claimed “we won’t fix on resolving that [authorship] question,” she joined Shapiro in dismissing skeptics with the offensive and nonsensical epithet “Shakespeare deniers” (once by Gladstone, three times by Shapiro). This epithet recalls the comparison to Holocaust deniers. (For more discussion of why terms like “anti-Shakespearean” or “Shakespeare denier” are so ridiculous and unhelpful, see, e.g., Wildenthal 2019, Preface, x–xi.)

Both Shapiro and Gladstone embraced the false meme that authorship doubts did not arise before the mid-19th century. While they briefly acknowledged a few anti-Stratfordian arguments, both made clear they were “far more interested,” “not [in] what people thought, but why they thought it” (my emphases; first quotation by Gladstone, second by Shapiro). This was consistent with the primary focus of Shapiro’s 2010 book, and the 2013 Edmondson & Wells anthology, both of which mainly sought to analyze the SAQ (very ineptly and unfairly) as a cultural phenomenon, making hardly any serious effort to engage the specific merits of the issue.

And why do doubters doubt, in Shapiro’s condescending psychoanalytical imagination? He first suggested that the SAQ is a mere infantile obsession, mockingly imitating the childish voice of a fourth-grader — apparently an impressively well-informed young student! — who dared to ask him an authorship question. Shapiro suggested he felt inhibited from bullying that innocent young questioner into silence, “like I do in my Columbia classrooms, and say, that’s rubbish and I’ll fail you if you ask that question again.”

We must assume, I suppose, giving Shapiro the benefit of the doubt, that this was sarcastic humor. But his offhand comment, even if a joke, is revealing about the level of orthodox conformity that chills any discussion of the SAQ in academia. Would even an adult student hearing this, who perhaps hoped to obtain Shapiro’s coveted support as a mentor, or his supervision of a thesis, feel free to openly express authorship doubts?

Threats of ridicule, leave aside a failing grade, are a very effective social sanction. In fact, like name-calling, they constitute a form of psychological bullying. Most authorship doubters among Shapiro’s students probably stay fearfully closeted. Does he truly feel comfortable about that?

What is it about the SAQ that reduces even leading public intellectuals, even professors at our finest universities, to this kind of irrational fever? As a career teacher myself, I find it deeply troubling.

Shapiro then mentioned what he conceded were “some of the smartest people” in the history of authorship doubt: “Mark Twain, Sigmund Freud, Henry James, Helen Keller, it’s a long list.” Indeed it is. And yes, speaking of infantile obsessions, Shapiro the amateur shrink went on to psychoanalyze Freud (following unwisely in the amateur footsteps of Schoenbaum and Wells). How do you spell chutzpah again?

But why — why? — did this long line of brilliant, diverse, and thoughtful people join what Shapiro derided as “this company of Shakespeare deniers”? Well, according to Shapiro, “for really complicated and very interesting and sometimes sad reasons” they apparently, somehow, just “had to deny his authorship.”

At this point, Gladstone interrupted to ask whether the SAQ might “start with the fact [that] there’s very little documentary evidence” for the Stratfordian theory. By gosh, she might be on to something there. Could it be that people of this caliber might actually be swayed by a reasoned assessment of facts?

But Gladstone promptly backed off, as Shapiro’s own students perhaps often feel compelled to do, when he kept talking right over her, recycling the stock Stratfordian claim (another false meme) that we supposedly have more relevant evidence about Shakespeare than about most of his peers.

No. We don’t. And so it goes. (See, e.g., Price, 112–58, 296–322, and “Shakespeare Authorship 101” on the SOF website.)

Conclusion

The snobbery and other slanders discussed here, in the final analysis, are bullying diversionary tactics for those Stratfordians who seem unwilling to confront the implausibility of their own theory. The comparison to Holocaust denial is by far the worst. No one in their right mind would want to be associated with anything as morally repugnant and irrational as Holocaust denial. So leveling this charge against the SAQ has the effect of tainting the entire issue, scaring off students and others from wanting to touch it with a ten-foot pole.

The obvious intent of all these slanders, and their sad result to some extent, is to shut down discussion of a serious and important literary and historical issue — and to intimidate many up-and-coming young scholars in the field of Shakespeare studies. The message is clear — they should not go anywhere near what has become tantamount to a verboten heresy.

Such blatantly anti-intellectual tactics are more reminiscent of the medieval era than the age of enlightenment in which we like to think we live.

Sadly, from the conventional Stratfordian perspective, the SAQ never seems to be about the simple factual and historical issue at its heart: Does the available evidence, fully considered in context, raise reasonable questions about who actually wrote these particular works of literature?

Can we please just focus on the merits of this issue and set aside all the name-calling? Can we please leave behind, once and for all, this ad hominem nonsense about snobbery, comparisons to Holocaust denial, and all the rest?

Is that really too much to ask?

Bryan H. Wildenthal is Professor of Law Emeritus and former SOF Trustee; A.B., J.D., Stanford University.

This article is dedicated to my beloved husband Ashish, who so generously supports all my endeavors. The article is copyright 2019 by Bryan H. Wildenthal and the Shakespeare Oxford Fellowship. Permission granted to copy and distribute it (in whole or in part) for any nonprofit personal or educational use, on condition that all references and copies credit the author and provide an acknowledgment and link to this publication on the SOF website. All photographs in this article are in the public domain (Whitman, 1854 engraving; Keller, c. 1904; Twain, c. 1906; Malcolm X, 1964).

This article is dedicated to my beloved husband Ashish, who so generously supports all my endeavors. The article is copyright 2019 by Bryan H. Wildenthal and the Shakespeare Oxford Fellowship. Permission granted to copy and distribute it (in whole or in part) for any nonprofit personal or educational use, on condition that all references and copies credit the author and provide an acknowledgment and link to this publication on the SOF website. All photographs in this article are in the public domain (Whitman, 1854 engraving; Keller, c. 1904; Twain, c. 1906; Malcolm X, 1964).

Much of this article appeared in somewhat different form in the conclusion of my book Early Shakespeare Authorship Doubts (2019) (Part V, 330–45). Free excerpts of the book are available here on SSRN (if prompted to create an account, “download without registration” at right); full hardcover version available here; full paperback here; also here on Amazon. Most of my scholarly writings relating to law or Shakespeare (some relate to both) are available here on SSRN. I am also the author of a textbook on law and history (Native American Sovereignty on Trial, 2003) and numerous articles in leading law reviews (mainly on constitutional law and history), including one on the Civil War-era 14th Amendment to the U.S. Constitution cited in an opinion of the U.S. Supreme Court, two concurring opinions, and numerous briefs on both sides, in major decisions by the Court in 2010 (McDonald v. Chicago) and 2019 (Timbs v. Indiana).

Bibliography

Anderson, Mark, “Shakespeare” By Another Name: The Life of Edward de Vere, Earl of Oxford, the Man Who Was Shakespeare (2005).

Anderson, Mark, Alexander Waugh & Alex McNeil, eds., Contested Year: Errors, Omissions and Unsupported Statements in James Shapiro’s “The Year of Lear: Shakespeare in 1606” (Amazon Kindle, 2016).

Bate, Jonathan & Alexander Waugh. See Waugh & Bate.

Bravin, Jess, “Justice Stevens Renders an Opinion on Who Wrote Shakespeare’s Plays,” Wall Street Journal (April 18, 2009), p. A1.

Clinton, Hillary Rodham. See “Hillary Rodham Clinton: By the Book.”

Dudley, Michael, Gary Goldstein & Shelly Maycock, “All That Is Shakespeare Melts Into Air,” Oxfordian 19 (2017), p. 195, reviewing Gary Taylor & Gabriel Egan et al., eds., The New Oxford Shakespeare: Authorship Companion (2017).

Dutton, Richard, William Shakespeare: A Literary Life (1989).

Edmondson, Paul & Stanley Wells, Shakespeare Bites Back: Not So Anonymous (ebook, 2011).

_____, eds., Shakespeare Beyond Doubt: Evidence, Argument, Controversy (2013).

Erne, Lukas, “Biography and Mythography: Rereading Chettle’s Alleged Apology to Shakespeare,” English Studies 79:5 (1998), p. 430.

Foggatt, Tyler, “Justice Stevens’s Dissenting Shakespeare Theory,” New Yorker (online July 29, 2019; in print as “Dept. of Dissent: Poetic Justice,” Aug. 5, 2019, p. 16).

Gladstone, Brooke & James Shapiro (interview), “Our Shakespeare, Ourselves,” On the Media (WNYC Radio, Dec. 29, 2016).

Goldstein, Gary. See Dudley, Goldstein & Maycock.

Greenblatt, Stephen, Letter to the Editor, New York Times, Sept. 4, 2005 (comparing SAQ to Holocaust denial).

Grimes, William, “Joseph Sobran, Writer Whom Buckley Mentored, Dies at 64,” New York Times, Oct. 2, 2010, p. A17 (online Oct. 1, 2010).

“Hillary Rodham Clinton: By the Book” (interview), New York Times Book Review, June 14, 2014, p. 7 (online June 11, 2014).

Jiménez, Ramon, “The Case for Oxford Revisited,” Oxfordian 11 (2009), p. 45, rep. Shakespeare Oxford Fellowship Website.

Kamm, Oliver, “Conspiracism at The Atlantic,” Quillette (May 16, 2019).

Last Will. & Testament (2012). See Wilson & Wilson.

Lipstadt, Deborah E., Denying the Holocaust: The Growing Assault on Truth and Memory (1993, pap. ed. 1994).

Malcolm X & Alex Haley, The Autobiography of Malcolm X (1965) (citations to Ballantine rep. 1973).

Marcotte, Amanda, “The Unsavory Motivations of the Shakespeare Truthers” (Dec. 29, 2014), Rawstory.

Marino, James J., Owning William Shakespeare: The King’s Men and Their Intellectual Property (2011).

_____, “Anonymous Is Terrible, But We’re to Blame” (Nov. 1, 2011), Penn Press Log.

_____ (as “Doctor Cleveland”), “Shakespeare, Oxford, and the 1%” (Nov. 3, 2011), Dagblog.

_____ (as “Doctor Cleveland”), “Shakespeare ‘Authorship Debates’ and Amateur Scholarship” (Dec. 31, 2014), Dagblog.

May, Steven W., “The Poems of Edward de Vere, Seventeenth Earl of Oxford and of Robert Devereux, Second Earl of Essex,” Studies in Philology 77:5 (1980), p. 5.

Maycock, Shelly. See Dudley, Goldstein & Maycock.

McCrea, Scott, The Case for Shakespeare: The End of the Authorship Question (2005).

McNeil, Alex, Mark Anderson & Alexander Waugh. See Anderson, Waugh & McNeil.

Price, Diana, Shakespeare’s Unorthodox Biography: New Evidence of an Authorship Problem (2001, rev. 2012) (cited as Price to 2012 edition) (Shakespeare’s Unorthodox Biography is also the title of Price’s website, with updates to her book and additional scholarly work and commentary).

Regnier, Tom, “In Memoriam: Justice John Paul Stevens,” Shakespeare Oxford Fellowship Website (July 17, 2019).

Reisz, Matthew, “Shakespeare Studies Spat: Author and Journal Editors Feud Over Paper on Shakespeare’s Identity,” Inside Higher Ed (Sept. 11, 2014) (discussing Gary Taylor’s comparison of SAQ to Holocaust denial).

Rosenbaum, Ron, “10 Things I Hate About Anonymous and the Stupid Shakespearean Birther Cult Behind It,” Slate (Oct. 27, 2011).

Schoenbaum, Samuel, Shakespeare’s Lives (1970, rev. 1991) (citations to 1991 edition).

Shahan, John M., Shakespeare Authorship Coalition (SAC), “SAC Letters to [Shakespeare] Birthplace Trust [SBT] and RSC [Royal Shakespeare Company] re: Removal of Stanley Wells’ False and Libelous Claims About Authorship Doubters” (April 5, 2010, June 17, 2014, and Jan. 20, 2015).

Shapiro, James, Contested Will: Who Wrote Shakespeare? (2010).

_____, The Year of Lear: Shakespeare in 1606 (2015).

_____, “Shakespeare Wrote Insightfully About Women. That Doesn’t Mean He Was One.” Atlantic (online June 8, 2019).

_____, “An Unexpected Letter From John Paul Stevens, Shakespeare Skeptic,” New Yorker (online Aug. 6, 2019).

Shapiro, James & Brooke Gladstone. See Gladstone & Shapiro.

Shermer, Michael, Why People Believe Weird Things: Pseudoscience, Superstition, and Other Confusions of Our Time (1997, rev. 2002).

Sobran, Joseph, Alias Shakespeare: Solving the Greatest Literary Mystery of All Time (1997).

Steinburg, Steven, “The ‘Post-Truth World’ of Sir Jonathan Bate” (Jan. 30, 2018), reviewing Waugh & Bate (2017).

Stritmatter, Roger, ed., Poems of Edward de Vere, 17th Earl of Oxford, v. 1, He That Takes the Pain to Pen the Book (2019, rev. ed. forthcoming 2021). See “Twenty Poems of Edward de Vere” (2018 website presentation).

Stritmatter, Roger & Bryan H. Wildenthal, “A Methodological Afterword,” in Stritmatter, Poems of Edward de Vere, v. 1 (2019), p. 175.

Taylor, Gary. See Reisz.

Twain, Mark, Is Shakespeare Dead? From My Autobiography (1909).

“Twenty Poems of Edward de Vere Echo in the Works of Shakespeare” (Preliminary Website Presentation, June 22, 2018). See also “Poetic Justice for the True Shakespeare?” (June 22, 2018) (linking to html and paginated pdf versions of the website presentation, and to Stritmatter’s book); Stritmatter, Poems of Edward de Vere (2019).

Waugh, Alexander, Mark Anderson & Alex McNeil. See Anderson, Waugh & McNeil.

Waugh, Alexander & Jonathan Bate, “Who Wrote Shakespeare?” (debate moderated by Hermione Eyre, Sept. 21, 2017; posted on YouTube Sept. 26, 2017).

Wells, Stanley & Paul Edmondson. See Edmondson & Wells.

Whitman, Walt, “What Lurks Behind Shakspere’s Historical Plays?” in Whitman, November Boughs (Philadelphia: McKay, 1888), p. 52.

Wildenthal, Bryan H., “Remembering Rollett and Debunking Shapiro (Again)” (2016, rev. 2017) (orig. pub. Shakespeare Oxford Fellowship Website, July 13, 2016) (also available here for free download in pdf format).

_____, “The Oxfordian Era on the Supreme Court” (2016, rev. 2020) (orig. pub. Shakespeare Oxford Newsletter 52:3, Summer 2016, p. 9).

_____, “Reflections on Spelling and the SAQ: ‘What’s in (the Spelling of) a Name?’,” Shakespeare Oxford Fellowship Website (Aug. 9, 2018) (also available here for free download in pdf format).

_____, Early Shakespeare Authorship Doubts (2019) (free excerpts available here; full hardcover version here; full paperback version here).

Wildenthal, Bryan H. & Roger Stritmatter. See Stritmatter & Wildenthal.

Wilson, Laura & Lisa Wilson (directors & producers), Last Will. & Testament (2012) (documentary film; see trailer here; DVD available on Amazon.com).

Winkler, Elizabeth, “Was Shakespeare a Woman?” Atlantic (June 2019), p. 86 (online May 10, 2019).

Winter, Bill, “Helen Keller, Shakespeare Skeptic” (April 25, 2017), Perkins School for the Blind Website.

[published July 15, 2019, updated 2021]

Membership dues cover only a fraction of our budget, including all our research, preservation and programming. Please support the SOF by making a gift today!

Blue Boar Tavern: Wassail Q&A

Tuesday Dec. 17, 8pm E / 5pm P

Sign up below for event invites!