The Oxfordian Era on the Supreme Court

Justice Antonin Scalia (1936–2016), Justice John Paul Stevens (1920–2019), and Other Authorship Skeptics on America’s Highest Court

by Bryan H. Wildenthal

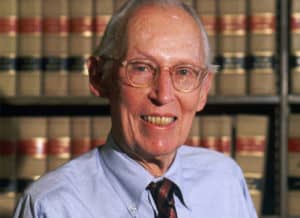

Published on the SOF website August 30, 2016 (revised and updated 2020). This article first appeared in shorter form in the Shakespeare Oxford Newsletter, v. 52, no. 3 (Summer 2016) (PDF here), pp. 9–13. It was originally written in 2016 to memorialize Justice Scalia. However, it also broadly surveys all five justices of the U.S. Supreme Court known to have openly rejected or questioned the traditional Stratfordian theory of Shakespeare authorship. Three of them — Justice Stevens (who died July 16, 2019), Justice Scalia, and Justice Harry A. Blackmun (1908–99) — declared themselves Oxfordians. Justice Stevens was by far the most outspoken on the authorship question. The other two avowed skeptics were Justice Lewis F. Powell Jr. and the first woman to serve on the Court, Justice Sandra Day O’Connor (Stevens reported that O’Connor also leaned toward the Oxfordian theory). The late Justice Ruth Bader Ginsburg also expressed interest in the issue, though never declaring herself a doubter.

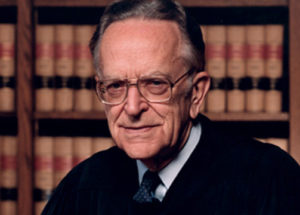

With the death of Justice Antonin Scalia on February 13, 2016, the United States Supreme Court lost one of its most brilliant and influential members — and Oxfordians lost one of the most distinguished figures ever to support the theory that Edward de Vere, 17th Earl of Oxford, was the true author of the works of “William Shakespeare.”

Justice Scalia, the first Italian American to serve on the nation’s highest tribunal, was appointed by President Ronald Reagan in 1982 to the U.S. Court of Appeals for the District of Columbia Circuit, and then to the Supreme Court in 1986.

Justice Scalia is best known as the intellectual leader of the Court’s conservative wing, an articulate exponent, sometimes caustic and controversial, of the closely allied legal philosophies of “textualism” and “originalism.” His firm belief was that laws — most importantly, the U.S. Constitution — should be read faithfully according to their text, informed by evidence of how they were publicly understood when enacted but without what he viewed as subjective and manipulable inquiries into the “intent” of the framers or “legislative history.” According to Scalia: “It is the law that governs, not the intent of the lawgiver.”[2] I have a deep interest, as a legal scholar and an Oxfordian who has taught and written (often critically, though always with respect) about Scalia’s judicial philosophy,[3] in his combined legacy for the law and the Shakespeare authorship question (SAQ).

We know few details of Justice Scalia’s Oxfordian views. Alas, I did not broach the subject on the four occasions (during 2001–07) on which I had the honor of meeting him, when he spoke at Thomas Jefferson School of Law in San Diego.[4] Scalia’s views on the SAQ were not widely known (at least not to me) before publication of a 2009 Wall Street Journal article, which quoted him recalling that as a child he received from a family friend “a monograph propounding de Vere’s cause.” (Jess Bravin, “Justice Stevens Renders an Opinion on Who Wrote Shakespeare’s Plays,” Wall Street Journal, April 18, 2009, p. A1.)

The “monograph” in question may have been John Thomas Looney’s 1920 book launching the Oxfordian theory, which was republished in a second American edition in 1948 (when Scalia was 12), or (less likely) This Star of England published in 1952, when Scalia was a 16-year-old student at Xavier High School, a Jesuit academy in Manhattan. (Looney, “Shakespeare” Identified in Edward de Vere the Seventeenth Earl of Oxford; Dorothy Ogburn & Charlton Ogburn Sr., This Star of England.) The leading biographies of Scalia do not mention his views on the SAQ, but do note that while at Xavier he “discovered his ability as an orator and a thespian and, as a senior, won the lead in Macbeth.”[5] As a Georgetown University history major, Scalia maintained his interest in drama and theatre and became president of the Mask and Bauble Theatre Club.[6]

All this suggests that Scalia was a Shakespeare lover and Oxfordian from a young age, almost certainly well before he began his third of a century of service as a judge, which followed years in which he was a law professor and an attorney in both private and government practice. There is something almost Falstaffian in one biographer’s description of him as “a connoisseur of food and drink, an opera lover, an enthusiast of many intellectual pursuits.”[7]

The apple did not fall far from the tree. His father, Salvatore Eugene Scalia, immigrated from Sicily in 1920 at age 17 and became a professor at Brooklyn College, a scholar of Romance languages, translator, and expert on Dante. His mother, Catherine Panaro Scalia, daughter of Italian immigrants herself, was a schoolteacher.[8] While Ben Jonson teasingly questioned whether Shakespeare knew “small Latin and less Greek,”[9] Scalia studied both for years.[10]

There appear to be some fascinating linkages between Scalia’s careful attention to the literal text of the law and his father’s belief in a literalist approach to translation. Anticipating his son’s constitutional originalism, Professor Scalia père believed that works of literature can truly be appreciated “only by direct ‘communion’ with the original ‘page’ itself … only by being able to interact directly with the text’s original, and not translated, words.”[11] One can imagine Scalia fils developing a fascination with the text of Shakespeare’s works that may in turn have led him to an abiding curiosity about who wrote that text — even if the identity and intent of the original author were mysteries whose importance he discounted in the field of law. But perhaps this biographical approach is too speculative — too much in the Stratfordian mode?

Fittingly, a recent study found both that Shakespeare tied Lewis Carroll (another pseudonym) among literary authors of fiction and drama, for most citations in Supreme Court opinions by justices then on the Court, and that Justice Scalia came out far in front of his colleagues in the total number of such citations in his own opinions.[12]

Upholding a criminal defendant’s Sixth Amendment right to confront his accuser at trial, Scalia offered one of the most vividly compelling uses of the Bard in the Court’s history:

Shakespeare was … describing the root meaning of confrontation when he had Richard the Second say: “Then call them to our presence — face to face, and frowning brow to brow, ourselves will hear the accuser and the accused freely speak….”[13]

Scalia seemed to delight in working in a bit of Shakespeare even when it didn’t really fit that well. Drawing a rather strained analogy in an employment discrimination case, he could not resist quoting the memorable exchange between Glendower and Hotspur in Henry IV. Glendower darkly boasted: “I can call Spirits from the vasty Deep.” Retorted Hotspur: “Why, so can I, or so can any man. But will they come…?”[14]

It would be fascinating to know if Scalia’s parents (or any of his many children) shared or share his love of Shakespeare — and possibly his dissent from Stratfordian orthodoxy? We Oxfordians know that such views often tend to run in the family. Scalia’s widow Maureen, a Radcliffe English major and his beloved wife for more than 55 years, apparently shared his love for Shakespeare and literature generally. But by Scalia’s own account, she registered a sharp spousal dissent on the authorship question. Acknowledging that she “is a much better expert in literature than I am,” he good-humoredly confessed that she had “berated” him with the suggestion that “we Oxfordians … can’t believe that a commoner” wrote the works. Ever the zesty debater, Justice Scalia offered the rejoinder (an important insight) that it may be “more likely” that Stratfordians “are affected by a democratic bias than the Oxfordians are … by an aristocratic bias.” (Bravin, Wall St. J., 2009.)

A Supreme Court Dominated by Authorship Doubters

It is poignant to realize that Justice Scalia’s appointment to the Supreme Court marked, in retrospect, the beginning of an Oxfordian Golden Age on the Court. His passing suggested that era might be drawing to a close, even as the Oxfordian cause advances overall. Unbeknownst to the public and perhaps to him, the newly seated Scalia, in 1986, joined no fewer than four justices already sitting on the Court who either then, or some years later, rejected the prevailing orthodox view that the Stratfordian theory of authorship has been established beyond any reasonable doubt.

Among those four additional members of the Court — Justices Harry A. Blackmun, Lewis F. Powell Jr., John Paul Stevens, and Sandra Day O’Connor — two (Blackmun and Stevens, plus possibly Powell and O’Connor as well) were or became Oxfordians like Scalia. This tantalizing 5-to-4 majority on the nation’s highest tribunal lasted only for the 1986–87 Term of Court, until Justice Powell’s retirement, and not all had yet developed their authorship views. But for one term, at least one third of the sitting justices were then or future Oxfordians — and 56% were definitely then or future non-Stratfordians!

The 1987 Moot Court Debate: A Crucial Turning Point

Things started to get even more interesting on September 25, 1987, just a few months after Powell’s retirement in June of that year, when Justices Blackmun and Stevens and their senior colleague, Justice William J. Brennan Jr., presided over the famous American University authorship debate (broadcast two months later on C-SPAN, Nov. 25, 1987), between law professors posing as counsel for William Shakspere of Stratford and Edward de Vere, Earl of Oxford. The panel unanimously found that the Oxfordian advocate failed to satisfy the high burden of proof — “clear and convincing evidence,” both that the Stratford man did not write the works and that Oxford did — arbitrarily imposed at the outset by Brennan, who pulled rank as senior presiding judge without consulting his colleagues. Justice Brennan rejected the lower “preponderance of the evidence” standard far more common in civil lawsuits, a standard often equated with “more likely than not” or anything above a 50% probability.[15]

Two decades later, the Shakespeare Authorship Coalition (SAC) under John Shahan’s leadership framed the issue more logically as whether “reasonable doubt” exists about the traditional Stratfordian attribution, doubt sufficient to stop the unjust ridicule and marginalization of authorship doubters and to justify serious and respectful study and debate of the SAQ in academia and among the media and public generally. (See SAC, Declaration of Reasonable Doubt, 2007.)

The 1987 panel comments contained hints of what was to come. Justice Brennan’s 1987 comments suggested he was a staunchly convinced Stratfordian. He retired in 1990 and died in 1997, never publicly amending his view. A lawyer acquainted with him, however, later asserted that “the more [Brennan] read about it, the more skeptical he became about the Stratfordian position.” (William S. Niederkorn, “A Historic Whodunit: If Shakespeare Didn’t, Who Did?” New York Times, Feb. 10, 2002, quoting William F. Causey.)

Justice Blackmun spoke next in 1987. Referring to Brennan’s vote against Oxford, Blackmun stated: “Well … I suppose that’s the legal answer. Whether it is the correct one causes me greater doubt….” Rather intriguingly, Justice Blackmun then said:

[T]he secondary question which has been emphasized today is whether the Oxfordians have proved their case. My own feeling is that they come closer to proving it than anyone else has, and whether that is enough is something that we’re supposed to say, I suppose; and yet, I am reluctant to say it.[16]

Hardly a ringing endorsement of the Stratfordian theory!

Justice Stevens also concurred, in 1987, that “the burden of proof was not met,”[17] but the remainder of his comments seemed very sympathetic to the unorthodox position. He confessed to “gnawing doubts that this great author may perhaps have been someone else.”[18]

These explicit declarations of “doubt” by Justices Blackmun and Stevens show that they already adopted, in 1987, the minimalist position of the Declaration of Reasonable Doubt promulgated by the SAC in 2007. Stevens signed the Declaration in 2009, along with Justice O’Connor. (SAC, “Notable Signatories.”)

Even more telling, Justice Stevens made clear he had read Ogburn’s landmark 1984 Oxfordian book.[19] He said flatly in 1987 that he was “persuaded that, if the author was not the man from Stratford, then there is a high probability that it was Edward de Vere,” and that Oxford’s “claim is by far the strongest of those [alternative authors] that have been put forward.” He correctly dismissed the anti-Oxfordian argument that some plays were supposedly written after Oxford’s death in 1604, noting that the “dating of the plays … is sort of a self-generating thing, where some of the dates were established on the assumption that Shakespeare [of Stratford] was in fact the author.”[20]

Best of all, Justice Stevens emphasized the importance of carrying on a respectful debate recognizing “the good faith and the honorable motives” of all participants. He expressly validated both the Oxfordian cause and the importance of the authorship inquiry itself — an implicit and powerful rebuke to all those who impatiently dismiss the issue.

Justice Stevens specifically thanked Oxfordians for “putting forth honest views that are based on careful and deliberate study and interest in a very, very difficult problem,” and declared that “this really incomparable author who has given so much to our civilization … does continue to merit the study that we have seen today and that led up to this controversy.” Finally, he concluded, “the doctrine of res judicata” — the rule that a lawsuit, once finally resolved, may not generally be relitigated — “does not apply to this.”[21]

Justice Stevens firmly identified himself as an Oxfordian to the New York Times in 2002 and to the Wall Street Journal in 2009. (Niederkorn, 2002; Bravin, 2009.) Stevens recalled that he and Justice Blackmun started developing more authorship doubts after the 1987 debate (see Bravin, 2009). Stevens accepted the “Oxfordian of the Year” Award later in 2009, jointly bestowed by the Shakespeare Oxford Society and Shakespeare Fellowship (see Shakespeare Oxford Newsletter 45:3, Dec. 2009, p. 1). But as far back as early 1991, less than four years after the 1987 debate, Stevens delivered a speech (published in 1992) that already strongly hinted at his support for the Oxfordian theory.[22]

Justice Blackmun went even further by 1992. The second edition of Ogburn’s book quoted him stating that “Oxfordians have presented a very strong — almost fully convincing — case,” and that if he again “had to rule on the evidence presented, it would be in favor of the Oxfordians.”[23]

Thus, within just a few years, fulfilling the prediction of Justice Stevens that the matter would not stay settled, the original verdict of 1987 was effectively reversed.

Oxfordians ultimately won, in effect, a 2-to-1 judgment against the Stratford theory and in favor of Edward de Vere — from the most distinguished neutral panel of judges ever to read and hear such a thorough presentation of the evidence and arguments.

It should be kept in mind that the evidence in favor of the Oxfordian theory has been substantially strengthened since 1987. A major new study of Vere’s early poems shows they have hundreds of compelling echoes in the canonical “Shakespeare” poems and plays. This reinforces and corroborates three major additional categories of evidence for Vere as the true Shakespeare that have been dramatically developed since 1987: biographical parallels explored in Mark Anderson’s “Shakespeare” By Another Name (2005) and Cheryl Eagan-Donovan’s acclaimed 2018 documentary, Nothing Is Truer Than Truth; parallels in Vere’s private letters explored by William Plumer Fowler (1986), Joseph Sobran (1997), Gary Goldstein (2016), and Bonner Miller Cutting (2017); and parallels between verses marked in Vere’s personal copy of the Geneva Bible and biblical references in the Shakespeare canon, explored by Professor Roger Stritmatter starting in the 1990s.[24]

During those same years since 1987, still more holes have been blown in the capsizing Stratfordian theory, including by Diana Price’s study of Shakespeare’s missing literary paper trail (2001), Katherine Chiljan’s well-documented book (2011), and Richard Paul Roe’s 2011 study of Shakespeare’s Italian references.[25]

Justice Powell was also revealed as an emphatic anti-Stratfordian in a statement quoted in the 1992 edition of Ogburn’s book (though Powell did not explicitly declare himself an Oxfordian). Powell’s disbelief in the orthodox view apparently long preceded the 1987 debate. Powell, as quoted in 1992, declared that he “never thought that the man of Stratford-on-Avon wrote the plays of Shakespeare.”[26]

This non-Stratfordian era on the U.S. Supreme Court, however, now seems over. Justice Powell retired in 1987 and died in 1998. Justice Blackmun retired in 1994 and died in 1999. Justice Scalia’s views, as noted earlier, were not publicized until 2009. As noted at the outset of this article, he died in office in 2016, the last known Oxfordian among active members of the Court. Justice Stevens retired in 2010 and died in 2019. Intriguingly, he was born on April 20, 1920 — less than two months after Looney published his landmark statement of the Oxfordian theory.

The 2009 Wall Street Journal article indicated that Justice O’Connor was not a Stratfordian, but was less clear about whether she was an Oxfordian and revealed nothing about the origins of her views. Justice Stevens eagerly testified that she leaned toward Oxford: “Sandra is persuaded that it definitely was not Shakespeare … [and was] more likely de Vere than any other candidate.” But Justice O’Connor herself, in line with her 2009 signing of the SAC’s Declaration of Reasonable Doubt, stated for the record only that “it might well have been someone other than our Stratford man.” (Bravin, Wall St. J., 2009.) O’Connor’s views on the SAQ were not (to my knowledge) publicized until 2009 and she had already retired by then (in 2006). She is now reportedly in declining health and no longer speaks publicly.

John Shahan reports that Justice Scalia declined an invitation to sign the Declaration of Reasonable Doubt. Scalia cited a general policy against signing petitions and expressed surprise that anyone would care about his views on the SAQ. Justices Powell and Blackmun died before the Declaration was issued, but are listed as prominent past authorship doubters.[27]

Authorship doubters continue to reach out to the justices. The same 2009 Wall Street Journal article, just months before Justice David Souter retired, quoted him as having “no idea” who the true author of the works of Shakespeare was. The late Justice Ruth Bader Ginsburg, well known as a Shakespeare aficionado[28] (and close personal friend of Justice Scalia; see endnote 4), said in the same article that she had “no informed views” about the authorship question, but expressed some interest in alternative candidates (though not endorsing any). (Bravin, Wall St. J., 2009.)

Neither Justice Ginsburg nor Justice Souter ever signed the SAC Declaration of Reasonable Doubt, and it would be a stretch to claim either as a clearcut non-Stratfordian based on what is publicly known. But it is certainly interesting that they declined to endorse the view of leading academic Stratfordians that no educated person should have any doubt at all about the orthodox authorship attribution. And it is interesting that Justice Ginsburg openly expressed interest in alternative authorship candidates.

With Justices Stevens and Scalia still actively serving Oxfordians in 2009, and Chief Justice John Roberts and Justices Clarence Thomas and Samuel Alito declining to comment, this left Stratfordians, at the time of the 2009 Wall Street Journal article, in a rather embarrassing position. They were able to claim only two overt supporters — Justices Anthony Kennedy and Stephen Breyer — a mere 22% of the active Court at that time! (Bravin, Wall St. J., 2009.)

As we look back on the last thirty years, we can reflect on a remarkable period in the Supreme Court’s history. Justice Scalia, given his strongly stated views on so many difficult issues that came before the Court, will probably always be controversial.[29] But we should remember and admire him for his patriotism, his dedication to public service, his intellectual brilliance, and his sheer love of family, life, and literature. He was also a man of deeply abiding religious faith who loved the ancient traditions of his Roman Catholic Church. Justice Scalia always insisted his religious beliefs had no influence on his legal philosophy or role as a judge. I am not aware of any reason to draw a connection between his religion and his views on the authorship of Shakespeare.[30]

Indeed, the history recounted here is a good reminder, in these divisive and troubling years in which we continue to live, that the SAQ is a shared enthusiasm that has long brought together people of otherwise dramatically diverse religious, political, and other views.

A mystery I have not been able to illuminate is the extent to which the Supreme Court justices may have influenced each other’s views about Shakespeare. It is well known among Court-watching lawyers that the justices have surprisingly little influence on each other’s legal views, typically operating almost like nine separate law offices. Nor, according to many accounts, are the Court’s private conferences (contrary to what one might hope) the scene for much deep philosophical discussion—rather, apparently, more like what diplomats call “an exchange of views.” The justices seem to debate each other mostly through the public media of oral arguments and published opinions.

What we do know, as traced above, suggests that Justices Stevens and Blackmun interacted quite a bit regarding their Oxfordian interests, and perhaps with Justice O’Connor too. Stevens’s comments quoted earlier suggest he may have engaged in some friendly efforts to bring O’Connor around to the Oxfordian cause. But the views of Justices Scalia and Powell appear to have been well set long before they came to the Court.

And even though Justices Scalia and Ginsburg were, as we have seen, close friends who shared interests in opera and literature (especially Shakespeare), no suggestion has emerged that the SAQ ever came up in their tête-à-têtes. Still, as noted above, Justice Ginsburg demurely declined to endorse the Stratfordian theory and expressed some interest in the SAQ.

In any event, perhaps what is most striking is that these skeptical justices have spanned the entire ideological spectrum on the Court, from Justice Scalia on the “right” to Justices Powell and O’Connor in the “center” to Justices Stevens and Blackmun (and the interested observer Justice Ginsburg) on the “left.” As a career-long teacher of constitutional law, I would however offer the same cautionary caveat I often have to my students: that such simplistic labels fall far short of capturing the complexity and unpredictability of these judges.

They have all taken their oath to uphold the Constitution seriously. We should also take seriously, as so many of them have, our pursuit of the truth about who wrote Shakespeare.

Endnotes

[1] Professor of Law Emeritus; A.B., J.D., Stanford University; former SOF Trustee.

This article is dedicated to my beloved husband Ashish, who so generously supports all my endeavors. The article is copyright 2016, 2020, by Bryan H. Wildenthal and the Shakespeare Oxford Fellowship. Permission is granted to copy and distribute it (in whole or in part) for any nonprofit personal or educational use, on condition that all references and copies credit the author and provide an acknowledgment and link to this publication on the SOF website. All photographs in this article are in the public domain. The article first appeared in shorter form in the Shakespeare Oxford Newsletter, vol. 52, no. 3 (Summer 2016) (PDF here), pp. 9–13. The website version was cited on SCOTUS Blog (Aug. 31, 2016).

This article is dedicated to my beloved husband Ashish, who so generously supports all my endeavors. The article is copyright 2016, 2020, by Bryan H. Wildenthal and the Shakespeare Oxford Fellowship. Permission is granted to copy and distribute it (in whole or in part) for any nonprofit personal or educational use, on condition that all references and copies credit the author and provide an acknowledgment and link to this publication on the SOF website. All photographs in this article are in the public domain. The article first appeared in shorter form in the Shakespeare Oxford Newsletter, vol. 52, no. 3 (Summer 2016) (PDF here), pp. 9–13. The website version was cited on SCOTUS Blog (Aug. 31, 2016).

See also my book Early Shakespeare Authorship Doubts (2019). Free excerpts are available here on SSRN (if prompted to create an account, “download without registration” at right); full hardcover version available here; full paperback here; also here on Amazon. Most of my scholarly writings relating to law or Shakespeare (some relate to both) are available here on SSRN. I am also the author of a textbook on law and history (Native American Sovereignty on Trial, 2003) and numerous articles in leading law reviews (mainly on constitutional law and history), including one on the Civil War-era 14th Amendment to the U.S. Constitution cited in an opinion of the U.S. Supreme Court, two concurring opinions, and numerous briefs on both sides, in major decisions by the Court in 2010 (McDonald v. Chicago) and 2019 (Timbs v. Indiana).

[2] Scalia, “Common-Law Courts in a Civil-Law System: The Role of United States Federal Courts in Interpreting the Constitution and Laws,” in Scalia et al., A Matter of Interpretation: Federal Courts and the Law (Amy Gutmann ed. 1997), p. 17 (emphasis in original), quoted in Wildenthal, “Nationalizing the Bill of Rights: Revisiting the Original Understanding of the Fourteenth Amendment in 1866-67,” 68 Ohio State Law Journal 1509, 1529 (2007). My latter article was itself, in a nice twist, cited several times in the opinion of the Court joined by Justice Scalia in McDonald v. Chicago, 561 U.S. 742, 763 n. 10 (2010) (upholding application to state and local governments of the Bill of Rights, in particular the Second Amendment right to keep and bear arms, via the Fourteenth Amendment); see also id. at 829 n. 10, 830 n. 12, 841 (Thomas, J., concurring in part and concurring in judgment, also citing my article). For more on Scalia’s constitutional philosophy, see, e.g., Scalia, “Originalism: The Lesser Evil,” 57 University of Cincinnati Law Review 849 (1989), George Kannar, “The Constitutional Catechism of Antonin Scalia,” 99 Yale Law Journal 1297, 1303–08 (1990), Ralph A. Rossum, Antonin Scalia’s Jurisprudence: Text and Tradition (2006), and James B. Staab, The Political Thought of Justice Antonin Scalia: A Hamiltonian on the Supreme Court (2006).

[3] In addition to my 2007 article (cited n. 2), see, e.g., Wildenthal, “The Right of Confrontation, Justice Scalia, and the Power and Limits of Textualism,” 48 Washington & Lee Law Review 1323 (1991).

[4] Justice Scalia was a personal friend, as was Justice Ruth Bader Ginsburg, of my own dear friend and faculty colleague Professor Emeritus Susan Tiefenbrun. Thanks largely to Susan’s efforts, both justices generously visited Thomas Jefferson School of Law on multiple occasions and taught several times in the school’s former summer overseas program at the University of Nice, France. Odd as it may seem, Justices Scalia and Ginsburg themselves, poles apart ideologically (admired heroes of the Right and Left respectively), were themselves longtime personal friends. See, e.g., Nina Totenberg, “Scalia v. Ginsburg: Supreme Court Sparring, Put to Music,” National Public Radio, July 10, 2013. The photograph at the beginning of this article was taken by Susan’s husband, Dr. Jonathan Tiefenbrun.

I became interested in the SAQ in 2000, but did not embrace the Oxfordian theory until around 2005. On one of the last two occasions I met Scalia (I think in 2006), Susan and I enjoyed a private lunch with him and two other faculty colleagues (the two U.S. marshals guarding him sat at a nearby table in a virtually empty restaurant). It would have been the perfect opportunity to discuss the SAQ, had I only known! Instead, we chatted about other safely historical topics, avoiding (of course) any discussion of the Court’s current caseload or the awkward subject of Scalia’s own judicial opinions (my colleagues and I all sympathized much more with the progressive Ginsburg). I am myself, however, also sympathetic to the textualist-originalist constitutional philosophy, though my take on it differs from Scalia’s. That, and what I now know to be our shared Oxfordian views, causes me to feel a certain kinship with him, despite our many disagreements on matters of the law.

[5] Joan Biskupic, American Original: The Life and Constitution of Supreme Court Justice Antonin Scalia (2009), p. 21; see also Bruce Allen Murphy, Scalia: A Court of One (2014), p. 18. Murphy recounted “the Shakespeare Principle” that Scalia recalled being taught by one of his Jesuit teachers at Xavier: “Mister, when you read Shakespeare, Shakespeare’s not on trial — YOU ARE!” Scalia said he “always thought that’s a very good prescription for life.” Id., pp. 16–17. Biskupic’s biography was presumably written before Scalia’s Oxfordian views were publicly revealed in the 2009 Wall Street Journal article. Murphy’s biography appeared five years later, but still did not mention Scalia’s views on the SAQ.

See Looney, “Shakespeare” Identified in Edward de Vere the Seventeenth Earl of Oxford (London: Cecil Palmer, 1920, rep. New York: Stokes, 1920, available in Google Books; 2d ed., New York: Duell, Sloan & Pearce, 1948; 3d ed., Ruth Loyd Miller ed., Port Washington, N.Y.: Kennikat Press & Jennings, La.: Minos Publishing, 2 vols., 1975; 4th ed., James A. Warren ed. 2018, 1st printing, Forever Press, 2d printing, Veritas Publications, 2019).

[6] Biskupic (cited n. 5), p. 24.

[7] Biskupic (cited n. 5), p. 67.

[8] Biskupic (cited n. 5), pp. 11–17.

[9] This famous and ambiguous line in Jonson’s First Folio dedication poem may easily be read as conditional (“though thou hadst small Latin, and less Greek … I would not seek” = “even if you had” etc.), a point apparently first noted in 1879 by a Stratfordian scholar but typically overlooked or ignored by Stratfordians ever since. C.M. Ingleby, Shakespeare’s Centurie of Prayse (1879), pp. 151–52, cited in Charlton Ogburn (Jr.), The Mysterious William Shakespeare: The Myth and the Reality (1984), pp. 231-33, and Richard F. Whalen, “ ‘Look Not on This Picture’: Ambiguity in the Shakespeare First Folio Preface,” Shakespeare Matters 10:3 (Summer 2011), pp. 1, 29, 35; see also, e.g., George Greenwood, The Shakespeare Problem Restated (1908), pp. 474–75 & n. 1 (citing a 1907 article by German scholar Konrad Meier); Dorothy Ogburn & Charlton Ogburn (Sr.), This Star of England (1952), pp. 1215–16 & n. 17 (citing Meier and Greenwood); Whalen, Shakespeare: Who Was He? (1994), pp. 55, 158 n. 10; Roger Stritmatter, “Ben Jonson’s ‘Small Latin and Less Greek’: Anatomy of a Misquotation,” Part 1: Setting the Stage, Oxfordian 19 (2017), p. 9; Part 2, Oxfordian 20 (2018), p. 83.

[10] Kannar (cited n. 2), p. 1316.

[11] Kannar (cited n. 2), p. 1316.

[12] Scott Dodson & Ami Dodson, “Literary Justice,” 18 Green Bag 2d 429 (2015).

[13] Coy v. Iowa, 487 U.S. 1012, 1016 (1988) (quoting Richard II, act 1, sc. 1), quoted in Wildenthal, “Right of Confrontation” (cited n. 3), p. 1333 & n. 48 (Wildenthal also recalling a memorable clash between Justices Douglas and Harlan over the meaning of Edmund’s “Why bastard, wherefore base?” soliloquy, King Lear, act 1, sc. 2, in a 1968 case concerning the law of illegitimacy).

[14] Henry IV, Part 1, act 3, sc. 1, quoted in Johnson v. Santa Clara County Transportation Agency, 480 U.S. 616, 674 (1987) (Scalia, J., dissenting). Scalia sought to mock the majority’s claim that Mr. Johnson, the purported victim of affirmative action favoring women, was not “automatically excluded from consideration” but was “able to have [his] qualifications weighed against those of other applicants.” Id. at 638, quoted at 674. The suggestion was that Johnson, like Glendower, might call upon “consideration” but it was a foregone conclusion that no favorable decision would “come.”

[15] After Justice Blackmun weakly protested that “you didn’t clear that with the rest of us,” Justice Brennan bluntly reasserted his ruling and stated that if his colleagues disagreed, “let them write the dissents.” Justice Stevens then joked that the standard could be “beyond a reasonable doubt” to match the letters of the “Bard.” Brennan offered nothing to support his high bar except a false premise: that no authorship doubts were expressed prior to the 1700s. “In re Shakespeare: The Authorship of Shakespeare on Trial,” 37 American University Law Review 819 & n. * (1988) (“Opinions of the Justices”). But see generally Wildenthal, Early Shakespeare Authorship Doubts (2019). See generally “In re Shakespeare: The Authorship of Shakespeare on Trial” (cited above), pp. 609–826, for the preface by David Lloyd Kreeger (the lawyer and philanthropist who was the main organizer of the event), articles and briefs by American University Law Professors Peter Jaszi (for Oxford) and James Boyle (for Stratford), and the transcript of the justices’ comments (video of the entire debate may be streamed for free, audio download for 99 cents, on the C-SPAN website here). For a useful account of the whole affair, see James Lardner, “The Authorship Question,” New Yorker, April 11, 1988, p. 87.

[16] “Opinions of the Justices” (cited n. 15), p. 822.

[17] “Opinions of the Justices” (cited n. 15), p. 824.

[18] “Opinions of the Justices” (cited n. 15), p. 825.

[19] Ogburn (1984) (cited n. 9). The publication of Ogburn’s book in 1984 was, indeed, the key factor instigating the 1987 debate.

[20] “Opinions of the Justices” (cited n. 15), p. 825.

[21] “Opinions of the Justices” (cited n. 15), pp. 825–26.

[22] Stevens, “The Shakespeare Canon of Statutory Construction,” 140 University of Pennsylvania Law Review 1373 (1992) (based on his Max Rosenn Lecture at Wilkes University, Wilkes-Barre, Pa., April 30, 1991); see also Stevens, “Section 43(a) of the Shakespeare Canon of Statutory Construction,” 1 John Marshall Review of Intellectual Property Law 179 (2002) (based on his Beverly W. Pattishall Inaugural Lecture in Trademark Law at John Marshall Law School, Chicago, Oct. 17, 2001).

After Stevens died in 2019, the New Yorker also discussed his Oxfordian views. See Tyler Foggatt, “Justice Stevens’s Dissenting Shakespeare Theory” (online July 29, 2019; in print as “Dept. of Dissent: Poetic Justice,” Aug. 5, 2019, p. 16). Professor James Shapiro of Columbia University then launched a follow-up attack on Stevens’s views. Shapiro pretended to show respect for Justice Stevens, noting that it “say[s] a lot about this extraordinary man” that he “would engage so generously with a fellow-citizen [he] never met.” But Shapiro repaid that generosity by slandering Stevens just when he was unable to defend himself. Shapiro smeared him as a conspiracy theorist, outrageously likening his authorship views to “anti-vaxxer propaganda” and “belief that the moon landing was faked.” See Shapiro, “An Unexpected Letter From John Paul Stevens, Shakespeare Skeptic,” New Yorker (online Aug. 6, 2019); see also Wildenthal, “The Snobbery Slander” (2019); Wildenthal, “Remembering Rollett and Debunking Shapiro (Again)” (2016).

[23] Charlton Ogburn (Jr.), The Mysterious William Shakespeare: The Myth and the Reality (rev. 1992), p. vi (prefatory quotations preceding the table of contents); see also Niederkorn, N.Y. Times, 2002 (quoting Blackmun). The original publication of Ogburn’s book in 1984 was the main instigation of the 1987 debate. See note 19; Ogburn (1984) (cited n. 9).

[24] Professor Stritmatter’s doctoral dissertation on Vere’s Bible was completed in 2001 and is now available in a revised published version: The Marginalia of Edward de Vere’s Geneva Bible: Providential Discovery, Literary Reasoning, and Historical Consequence (4th ed. 2015). For two useful summaries of Stritmatter’s work on the Vere Bible, see Mark Anderson, “Thy Countenance Shakes Spears,” Harper’s (April 1999), p. 46, and Mark Anderson, “Shakespeare” By Another Name: The Life of Edward de Vere, Earl of Oxford, the Man Who Was Shakespeare (2005), app. A, pp. 381–92.

[25] See Anderson (2005) (cited n. 24); Richard Paul Roe, The Shakespeare Guide to Italy: Retracing the Bard’s Unknown Travels (2011); Diana Price, Shakespeare’s Unorthodox Biography: New Evidence of an Authorship Problem (2001, rev. 2012) (supplements and updates here); Katherine Chiljan, Shakespeare Suppressed: The Uncensored Truth About Shakespeare and His Works (2011, rev. 2016); see also Shakespeare Beyond Doubt? Exposing an Industry in Denial (John M. Shahan & Alexander Waugh eds. 2013).

[26] Ogburn (1992) (cited n. 23), p. vi.

[27] The SAC’s “Past Doubters” page notes that Powell’s and Blackmun’s comments quoted in Ogburn (1992) (cited n. 23), p. vi, were stated in letters written to Ogburn after the 1987 debate.

[28] Ginsburg participated in several Shakespeare-related events, including a mock appeal by Shylock, the anti-hero of The Merchant of Venice. Rachel Donadio, “Justice Ruth Bader Ginsburg Presides Over Shylock’s Appeal,” New York Times, July 27, 2016.

[29] The vacancy created by Justice Scalia’s death was consumed by an unseemly political brouhaha, in which a majority of the U.S. Senate engaged in an astonishing and historically unprecedented degree of obstruction by refusing even to consider President Obama’s nominee to replace him. See, e.g., Wildenthal, Academic Commentary, Jurist (Feb. 21, 2016); Wildenthal, “Memorandum on Supreme Court Vacancies and Confirmations During Presidential Election Years” (Feb. 20, 2016).

[30] A fair-minded summary of his Catholic religious upbringing, and the issue of how it may generally have influenced him, is provided in Biskupic (cited n. 5), pp. 19-26, 185-210.

Membership dues cover only a fraction of our budget, including all our research, preservation and programming. Please support the SOF by making a gift today!

Blue Boar Tavern: Wassail Q&A

Tuesday Dec. 17, 8pm E / 5pm P

Sign up below for event invites!