Roe, “Shakespeare Guide to Italy”: news and reviews

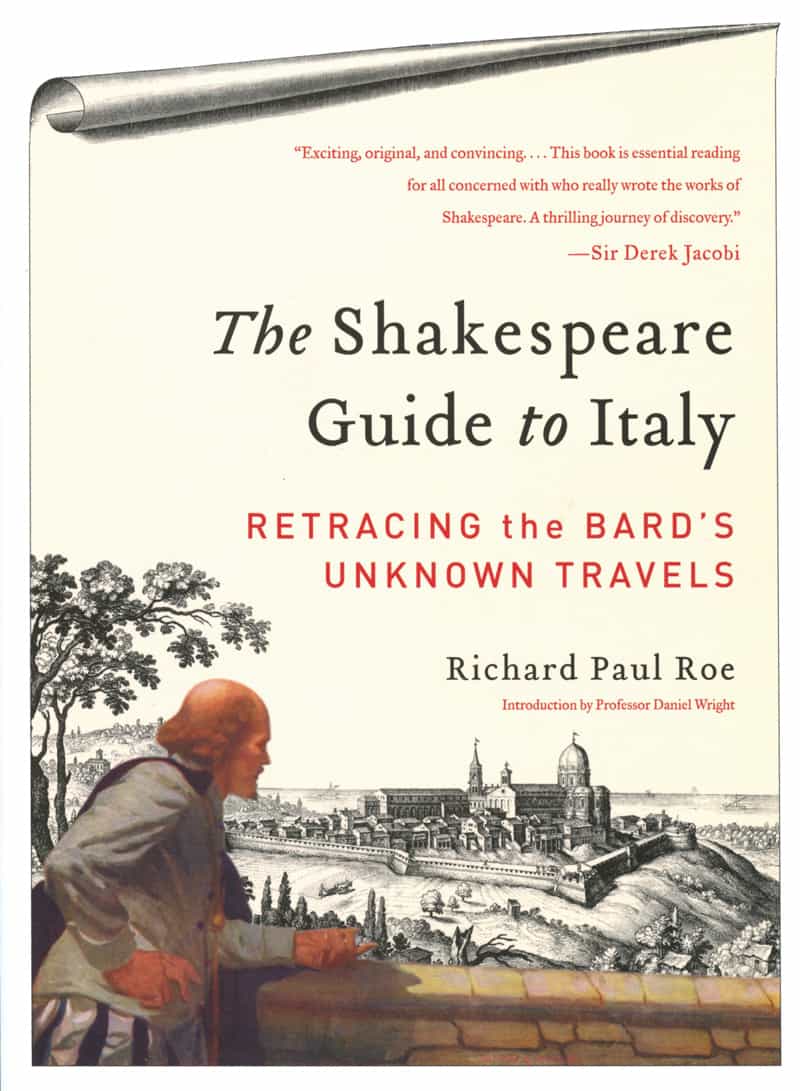

August 10, 2011 — Hilary Roe Metternich has provided a lovely slideshow and summary, available on the Huffington Post, of The Shakespeare Guide to Italy (2011), written by her late father Richard Paul Roe (1922–2010). Roe’s guide, as Metternich notes, is “an absorbing, insightful, easy-to-read journey into the ten [Shakespeare] plays set in Italy. [R]eading [it] will make your playgoing experience richer ….” And that’s true, she notes, even if you have no interest in the Shakespeare Authorship Question (SAQ).

August 10, 2011 — Hilary Roe Metternich has provided a lovely slideshow and summary, available on the Huffington Post, of The Shakespeare Guide to Italy (2011), written by her late father Richard Paul Roe (1922–2010). Roe’s guide, as Metternich notes, is “an absorbing, insightful, easy-to-read journey into the ten [Shakespeare] plays set in Italy. [R]eading [it] will make your playgoing experience richer ….” And that’s true, she notes, even if you have no interest in the Shakespeare Authorship Question (SAQ).

For those interested in the SAQ, Metternich observes, “it seems pretty irrefutable that whoever wrote those ten plays knew Italy ‘up close and personal.’ … [Roe] used as his guide only the words given to the plays’ characters by Shakespeare to speak … [and he] thoroughly checked [them] across Italy for their accuracy ….” The conclusion most readers will draw from Roe’s deservedly popular book is that “it’s hard to accept that William Shakespeare of Stratford-on-Avon picked up his detailed knowledge about that country in, say, a pub in London over a tankard of stout from some chatty traveling Italian traders ….”

Richard Paul Roe was honored in 2010 as Oxfordian of the Year. You can read memorial articles about him in Shakespeare Matters, v. 9, no. 3 (Fall 2010) (pp. 4–5), and the Shakespeare Oxford Newsletter, v. 47, no. 1 (Jan. 2011) (pp. 1–3, continuing on 22–23, not “18”). Virginia J. Renner’s review of his book is in Brief Chronicles, v. 3 (2011) (pp. 274–78).

Roe’s book, however, while strongly supporting the Oxfordian theory by implication, avoids taking any stance on who the real author “Shakespeare” might have been. Instead, as Metternich says, it “simply points to the astounding accuracy of the Italian plays, leaving it to the reader to ponder (if they want to) what such accuracy implies — as they pleasantly travel through one of the most beautiful and inspiring countries of the world.”

A review in Library Journal notes: “The thrill of discovery [Roe] felt throughout his quest leaps off the page …. The connections he draws among the plays and locales are backed up with pictures, maps, literary references, and well-documented arguments…. A fascinating look at a largely untouched aspect of Shakespeare’s identity and influences. Recommended for Shakespeare enthusiasts and scholars as well as travelers looking for a new perspective, this is also particularly intriguing as a companion to specific plays.”

The works of “William Shakespeare” (a likely pseudonym, probably using the Stratford player as a frontman) suggest the author was intimately familiar with the language, art, theatre, culture, customs, and geography of Italy, which permeate so many plays. But it’s difficult to imagine how the businessman and actor from Stratford-upon-Avon, traditionally credited as the author, could have gained such knowledge or experience. There’s no evidence he ever traveled outside England, which was extremely expensive and politically risky at the time.

Edward de Vere, the 17th Earl of Oxford (1550–1604), spent more than a year traveling in continental Europe in 1575–76, including extensive and formative time in Italy, visiting the very same cities (Venice, Verona, Padua, and others) in which several Shakespeare plays are set.

The Italian connections with the works of Shakespeare have been explored by these among many thoughtful scholars:

- Alexander Waugh expanded upon Roe’s studies in his brilliant chapter in Shakespeare Beyond Doubt? Exposing an Industry in Denial (Shahan & Waugh eds. 2013) (pp. 72–85).

- Italian scholar Noemi Magri, Ph.D., published numerous deeply informed and perceptive articles on the subject, collected in Such Fruits Out of Italy: The Italian Renaissance in Shakespeare’s Plays and Poems (2014).

- Cheryl Eagan-Donovan’s acclaimed documentary film, Nothing Is Truer Than Truth (2018), also examines this aspect of the authorship issue.

- The insights of Roe, Magri, and others have been refined, corrected, and developed in articles in The Oxfordian by Catherine Hatinguais, who has pursued the mystery of the “sycamores” (or plane trees) of Verona (v. 18, pp. 85–99, 2016), and travel by rivers and canals in northern Italy (v. 21, pp. 95–142, 2019). This is how scholarship should proceed. What a pity that most defenders of the Stratfordian theory content themselves with misguided mockery of Shakespeare’s imagined “mistakes” about Italian geography.

[published Aug. 10, 2011, revised and updated 2021]

Membership dues cover only a fraction of our budget, including all our research, preservation and programming. Please support the SOF by making a gift today!

Blue Boar Tavern: Wassail Q&A

Tuesday Dec. 17, 8pm E / 5pm P

Sign up below for event invites!