In Memoriam: Justice John Paul Stevens

by Tom Regnier

July 17, 2019

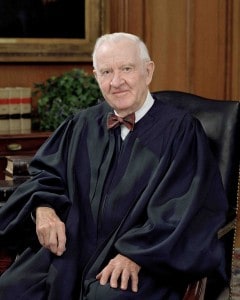

We in the Shakespeare Oxford Fellowship note with great sadness and enormous respect the passing of retired Supreme Court Justice John Paul Stevens (1920–2019), who was our Oxfordian of the Year in 2009. Justice Stevens was also a “notable signatory” of the Declaration of Reasonable Doubt About the Identity of William Shakespeare.

Justice Stevens was appointed to the U.S. Supreme Court by President Gerald Ford in 1975 and was in active service on the Court until 2010. His 35-year tenure on the Court was one of the longest in history. He became interested in the Shakespeare authorship question in 1987, when he participated in a moot court debate on the topic of Oxford vs. Shakespeare at American University in Washington, D.C. There, he was part of a three-justice panel that also included Justices William Brennan and Harry Blackmun.

Justice Brennan, the senior justice of the three, decided at the start that Oxfordians would have to prove their case by “clear and convincing” evidence — a higher standard than by a “preponderance of the evidence.” This virtually assured that the Stratfordians would win, but both Justices Stevens and Blackmun expressed strong doubts about the Stratfordian theory as they reluctantly cast their votes for the man from Stratford. Later, after studying the authorship question further, Stevens and Blackmun came to believe that Edward de Vere, the 17th Earl of Oxford, was the true author of Shakespeare’s works.

In 2003, while I was still in law school, I wrote a law review article on the Shakespeare authorship question in which I quoted an article that Justice Stevens wrote on the same topic. When my article was published in the University of Miami Law Review, I sent a courtesy copy to Justice Stevens. To my surprise, I received a letter from him on U.S. Supreme Court letterhead about a week later:

Many thanks for sending me a reprint of your fine article. Your discussion of inheritance law in Hamlet contains insights that are new to me. If you can send me another reprint, I would like to forward it to a friend in England who is becoming increasingly interested in the Oxfordian thesis. Incidentally, I think one reason why the scene involving Polonius and Reynaldo is so relevant to the authorship issue is its total irrelevance to the plot in the play itself.

Sincerely,

J.P. Stevens

The comment about Polonius referred to the many recognized parallels between Polonius and Lord Burghley, who was the Earl of Oxford’s father-in-law — one of the many, many clues linking Oxford to Shakespeare’s works. Of course, I sent Justice Stevens three reprints of my article, in case he had any other friends who were becoming increasingly interested in the Oxfordian thesis.

Justice Stevens expounded on his belief in Oxford as the true Shakespeare in an interview with Jess Bravin published in The Wall Street Journal on April 18, 2009: “Justice Stevens Renders an Opinion on Who Wrote Shakespeare’s Plays.” The article also outed his fellow Justices Scalia and O’Connor as authorship skeptics. Stevens expressed his view that “the evidence that [Shakespeare of Stratford] was not the author is beyond a reasonable doubt.”

For this eloquent public endorsement of the Oxfordian theory, Justice Stevens was named Oxfordian of the Year in 2009 by the Shakespeare Oxford Fellowship’s two predecessor organizations. I was chosen to be in the delegation that went to Washington, D.C., to present the award to him on November 12, 2009, along with Alex McNeil, Michael Pisapia, and Melissa Dell’Orto. (See website report, Nov. 2009, and newsletter report, Dec. 2009.)

Justice Stevens greeted us warmly in his chambers. He complimented me again on the article I had sent him six years earlier. All of us chatted about the authorship question for some time. It was a sublime half hour or so. Alex McNeil later said of Justice Stevens, “Having been a court administrator for three dozen years, I know judges, and he was truly a class act.”

In 1992, Justice Stevens had written an article in the University of Pennsylvania Law Review, “The Shakespeare Canon of Statutory Construction.” This was the article that I had quoted in my own article in 2003. Stevens, in his article, cited five canons of statutory construction — basic rules to aid the interpretation of difficult laws — and applied them to the authorship question. When considering the fourth canon, “consult the legislative history,” Justice Stevens found that a legislature’s silence is often a profound indication of its intent:

For present purposes, I shall confine my analysis of the fourth canon to the Sherlock Holmes principle that sometimes the fact that a watchdog did not bark may provide a significant clue about the identity of a murderous intruder. The Court is sometimes skeptical about the meaning of a statute that appears to make a major change in the law when the legislative history reveals a deafening silence about any such intent.

This concern directs our attention to three items of legislative history that arguably constitute significant silence. First, where is Shakespeare’s library? He must have been a voracious reader and, at least after he achieved success, could certainly have afforded to have his own library. Of course, he may have had a large library that disappeared centuries ago, but it is nevertheless of interest that there is no mention of any library, or of any books at all, in his will, and no evidence that his house in Stratford ever contained a library. Second, his son-in-law’s detailed medical journals describing his treatment of numerous patients can be examined today at one of the museums in Stratford-on-Avon. Those journals contain no mention of the doctor’s illustrious father-in-law. Finally — and this is the fact that is most puzzling to me, although it is discounted by historians far more learned than I — there is the seven-year period of silence that followed Shakespeare’s death in 1616. Until the First Folio was published in 1623, there seems to have been no public comment in any part of England on the passing of the greatest literary genius in the country’s history. Perhaps he did not merit a crypt in Westminster Abbey, or a eulogy penned by King James, but it does seem odd that not even a cocker spaniel or a dachshund made any noise at all when he passed from the scene.

It will be more than a cocker spaniel or a dachshund who mourns today for Justice Stevens. It will be those who think that the truth always matters. Thank you, Justice Stevens, for all you did to bring the truth to light.

For more information:

How many other Supreme Court Justices were Oxfordians or Shakespeare authorship doubters? Quite a few! Read this article by Professor Bryan H. Wildenthal.

Read “Justice Stevens Renders an Opinion on Who Wrote Shakespeare’s Plays,” Wall Street Journal (2009) (subscription required). The 2002 New York Times article in which Justice Stevens first clearly and publicly declared himself to be an Oxfordian is available here.

Watch the 1987 Shakespeare authorship debate held before Justices Brennan, Blackmun, and Stevens.

Read “The Shakespeare Canon of Statutory Construction” (1992) by John Paul Stevens.

Read “Could Shakespeare Think Like a Lawyer?” (2003) by Tom Regnier.

Read about “Justice Stevens’s Dissenting Shakespeare Theory” in The New Yorker (2019).

Read and sign the Shakespeare Authorship Coalition’s Declaration of Reasonable Doubt.

Watch this video tribute to Justice Stevens at the 2019 SOF conference at the Mark Twain House and Museum in Hartford, Connecticut.

Editorial Note: Tom Regnier passed away on April 14, 2020, less than a year after his hero Justice Stevens. Read the SOF obituary of Tom here.

[published July 17, 2019, updated April 2021]

Membership dues cover only a fraction of our budget, including all our research, preservation and programming. Please support the SOF by making a gift today!

Blue Boar Tavern: Wassail Q&A

Tuesday Dec. 17, 8pm E / 5pm P

Sign up below for event invites!