Shakespeare by the Numbers: What Stylometrics Can and Cannot Tell Us

book review by Ramon Jiménez

Hugh Craig and Arthur F. Kinney, eds., Shakespeare, Computers, and the Mystery of Authorship (Cambridge University Press, 2009). Review originally published in slightly different form, as “How Reliable Is Stylometrics? Two Orthodox Scholars Investigate,” in the Shakespeare Oxford Newsletter, v. 47, no. 1 (Jan. 2011), pp. 11–16; republished as “Stylometrics: How Reliable Is It Really?” in Shakespeare Beyond Doubt? (Shahan & Waugh eds. 2013), app. B, pp. 228–36; republished on the SOF website December 24, 2019.

See also this overview of the broader issue of stylometric analysis of literary works.

Over the course of the last thirty years, linguistic analysis by computer has become the favorite tool that scholars use to determine authorship of literary work. And their preferred hunting-ground has been the plays and poems of Shakespeare. Arthur F. Kinney, the editor of English Literary Renaissance, and Hugh Craig, an English professor at the University of Newcastle in Australia, have collected a group of essays that focuses on the authorship questions surrounding more than a dozen plays and parts of plays both in and out of the Shakespeare canon. More than half of the play-texts examined appeared in Shakespeare’s First Folio; two others — The Two Noble Kinsmen and Edward III — were subsequently added to the canon. Four other anonymous plays and fragments make up the balance.

The authors’ objective is to “resolve a number of questions in the Shakespeare canon, so that the business of interpretation, which is so often stymied by uncertainty of authorship, can proceed.” Their studies supply considerable additional evidence of Shakespeare’s participation, or lack of it, in the selected texts, but in most cases that evidence falls short of resolving the question. Citing Georges Braque’s remark that “One’s style is one’s inability to do otherwise,” they claim that “writers leave subtle and persistent traces of a distinctive style through all levels of their syntax and lexis,” the former being the writer’s arrangement of words, and the latter his vocabulary or word stock.

They lay out the case, with considerable biological detail, for the absolute individuality of verbal expression. This leads them to conclude that “a scene or an act will become uniquely identifiable.” To accomplish such identification, Craig and Kinney use “computational stylistics” to calculate the probability that a particular author wrote or did not write a particular body of text. Roughly speaking, their method is to compare an author’s use of two types of common words — function words and lexical words — in his known works with the use of the same words in an anonymous work or disputed section of text. It may be summarized in this series of steps:

- Select an appropriate “control group” of an author’s acknowledged plays and divide it into 2000-word segments, regardless of speech, act or scene divisions.

- For each segment, obtain a numerical score for the author’s use and non-use of a group of the 200 most common functional words occurring in Early Modern English drama, words such as and, you, and through. Functional words have syntactical rather than semantic uses.

- For each segment, obtain a numerical score for the author’s use and non-use of a group of selected lexical words. These are the words in a writer’s vocabulary that have semantic meaning.

- On two scatter plots, graphically display the individual scores for each test for each segment of 2000 words.

- The result is two scatter plots, on one of which a cluster of points indicates the author’s typical use of the 200 functional words. On the other scatter plot, the cluster indicates the author’s typical use of the selected lexical words. The statistical center of each cluster is the centroid.

- Conduct the same two tests for similar 2000-word blocks from an anonymous play or questionable fragment, and superimpose the scores on the scatter plot for the proposed author of the text.

- The physical distance of the scores for the subject segment of text from the centroid of the selected author’s cluster indicates the degree of probability that he wrote it.

The result is a mixed bag of conclusions, many of which confirm today’s scholarly consensus about what Shakespeare wrote and what he didn’t, but many others that conflict with recent studies by such scholars as Sir Brian Vickers, Thomas Merriam, Eric Sams, and Ward Elliott and Robert Valenza. In spite of their use of an array of statistical tools, such as Principal Component Analysis, “discriminant analysis,” the t test and the “Zeta” test, Craig and Kinney’s conclusions are subject to the same doubts as other methods of determining authorship that rely solely on detailed textual analysis.

One problem is the selection of the “control group” from a dramatist’s accepted work to develop the criteria to apply to questionable texts. In the case of Shakespeare, the authors chose 27 “core” plays — but excluded in their entirety the three Henry VI plays, the Folio King Lear, Macbeth, Measure for Measure, The Taming of the Shrew, Henry VIII, The Two Noble Kinsman, Timon of Athens, Titus Andronicus, and Pericles. Also excluded are Edward III, Edmund Ironside, and Thomas of Woodstock (1 Richard II), each of which has been attributed to Shakespeare in a full-length study by a reputable modern scholar. Admittedly, many of these plays, or parts of them, remain disputed, and are the actual subjects of Craig and Kinney’s analyses. But to exclude the entirety of half-a-dozen of Shakespeare’s earliest plays when attempting to establish his linguistic peculiarities is to limit and distort the definition of his style. This is particularly important in the case of Shakespearean authorship because much of the apocrypha, the disputed texts, are obviously his earliest work.

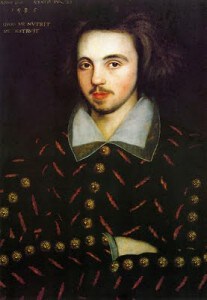

Shakespeare and Marlowe

The authors applied their function word and lexical word tests to each of the three Henry VI plays, using as their baseline the results from a control group of six undisputed Shakespeare plays, three histories and three comedies, that “he wrote about the same time.” Test results for Part 3 were sufficiently vague to cause them to discontinue any further analysis, but the results for Parts 1 and 2 suggested that portions of each play were not by Shakespeare. In the case of Part 1, their tests confirmed the opinions of numerous commentators, including Malone, Wilson, Cairncross, and Taylor, that the Temple Garden scene and the scenes involving John Talbot and his son were Shakespeare’s work. But Acts 1, 3 and 5, and three scenes in Acts 2 and 4 were the work of another writer or writers. Although they acknowledge that a third dramatist was probably involved, most likely Thomas Nashe, the authors assert that Marlowe was Shakespeare’s earliest collaborator, and that he and Shakespeare worked together on Parts 1 and 2 of Henry VI. Marlowe was responsible for, at least, “the middle part” of Part 1, involving Joan of Arc, and the Cade rebellion scenes in Part 2.

Their analysis of 1 Henry VI conflicts with the recent conclusion of Sir Brian Vickers that Thomas Kyd was the author of the play. In light of Vickers’ attribution, Craig and Kinney compared 1 Henry VI to a Kyd corpus of The Spanish Tragedy and Cornelia, and found “no affinities between Kyd and 1 Henry VI.” After expanding the Kyd corpus to include Soliman and Perseda, they found that “the 1 Henry VI segments remained firmly in the non-Kyd cluster.”

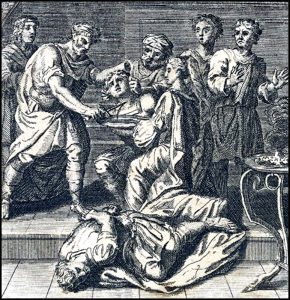

Three Anonymous Plays

[pullquote]The anonymous Arden of Faversham (1592) is the play in the Shakespearean Apocrypha that has most often been ascribed to Shakespeare, although it has been assigned to at least six other authors.[/pullquote]The anonymous Arden of Faversham (1592) is the play in the Shakespearean Apocrypha that has most often been ascribed to Shakespeare, although it has been assigned to at least six other authors. The most recent attribution was by Sir Brian Vickers, who agreed with T.S. Eliot that the author was Thomas Kyd. Arden was extravagantly praised and ascribed to Shakespeare by A.C. Swinburne, and more recently MacDonald P. Jackson has published several papers suggesting that Shakespeare had a major hand in it, most assuredly in scene 6 and scene 8, the “quarrel scene.” Craig and Kinney tested the author’s use of lexical words against the Shakespeare pattern obtained from the 27-play control group. The results suggest that Shakespeare was responsible for “the middle section,” comprising scenes 4 through 9, but the scores for the two longest scenes (1 and 15), and most of the rest of them, fall clearly out of the Shakespeare cluster. Further tests “gave no support for the idea that Marlowe or Kyd were collaborators in writing Arden of Faversham.” They agree with Jackson in assigning scenes 6 and 8 to Shakespeare, but are unable to ascribe the earliest or latest scenes to any other known dramatist.

In 1931, Arden was convincingly attributed to Edward de Vere, 17th Earl of Oxford by Eva Turner Clark, who cited dozens of identical words, phrases and dramatic devices in it that were echoed in subsequent Shakespeare plays, especially Richard III and the Henry VI trilogy. She argued persuasively that it was acted at court in early 1579 under the title Murderous Michael by the Earls of Oxford and Surrey and Lords Thomas Howard and Frederick Windsor, the latter being the son of Oxford’s half-sister Katherine. The first edition of the putative source of the play, Holinshed’s Chronicles, had been published less than two years earlier.

In 1931, Arden was convincingly attributed to Edward de Vere, 17th Earl of Oxford by Eva Turner Clark, who cited dozens of identical words, phrases and dramatic devices in it that were echoed in subsequent Shakespeare plays, especially Richard III and the Henry VI trilogy. She argued persuasively that it was acted at court in early 1579 under the title Murderous Michael by the Earls of Oxford and Surrey and Lords Thomas Howard and Frederick Windsor, the latter being the son of Oxford’s half-sister Katherine. The first edition of the putative source of the play, Holinshed’s Chronicles, had been published less than two years earlier.

The chapter on the anonymous Edmund Ironside reviews all the literature on the play, focusing especially on that since 1982, when Eric Sams published his extensive study demonstrating that it was Shakespeare’s apprentice work, and his alone, in about 1588. Most other commentators have derided Sams’ attribution and instead asserted that the author was heavily indebted to Shakespeare. According to the authors, the function word and lexical word tests that they applied to Ironside suggest that none of it was by Shakespeare. Furthermore, the application of similar tests comparing the Ironside sections against plays by Lyly, Peele, Greene, Marlowe and seven other playwrights produced no positive results. Thus, the authorship of Ironside, dated by most scholars in the 1590s, remains a mystery to everyone except those who agree with Sams’ convincing attribution to Shakespeare.

The authors subjected the two major episodes of Edward III — the so-called Countess scenes (1.2 through 2.2) and the French campaign scenes (3.1 through 4.3) — to the same function word and lexical word tests. Each segment makes up a third of the play. The results indicated that Shakespeare wrote the Countess segment, echoing a conclusion arrived at by most critics. But the authors’ results for the French campaign segment fail to support Shakespeare’s authorship. Further tests of word usage in both segments against that in undisputed plays by Marlowe, Peele and Kyd did not “support the idea” that any of them wrote either segment. Craig and Kinney thus consign two-thirds of Edward III to an unknown collaborator with Shakespeare. They describe as “flawed” the studies of Wentersdorf (1960), Lapides (1980), Slater (1988) and Sams (1996), all of whom concluded that Shakespeare wrote the entire play.

Further complicating the issue are the findings of Sir Brian Vickers, who in late 2008 asserted that his analysis of three-word collocations in the “non-Shakespearean” portions of Edward III (1.1, 3, and 5) revealed that they were by Thomas Kyd. A few months later, Thomas Merriam, another advocate of Shakespearean co-authorship, published the results of his “multi-dimensional analysis of relative frequencies of function words” in the same “non-Shakespearean” passages of Edward III. He found that Shakespeare’s collaborator was none other than Christopher Marlowe. But, contradicting all theories of co-authorship, Jonathan Hope, using “socio-historical linguistic evidence,” found little or no evidence of divided authorship in the play (The Authorship of Shakespeare’s Plays 1994). He considered it likely that Shakespeare wrote all of Edward III.

King Lear and The Spanish Tragedy

Various critics have speculated about the passages that were added to the first quartos of these two plays, Lear being firmly in the Shakespeare canon, and The Spanish Tragedy attached by a tenuous thread to Thomas Kyd. The authors found “a consistency in the distribution of some common function words” in both the Quarto Lear (1608) and the Folio Lear (1623), indicating that a single person or persons was responsible for the entirety of each text. When they then examined the approximately 900 words in F that did not appear in Q, they found that both function word and lexical word tests indicated that these passages were by Shakespeare. This is the view of most editors and critics.

The analysis of The Spanish Tragedy (Q1 1592) consisted of tests of the five passages of the Additions, comprising less than 500 lines, that appeared in the edition of 1602. These have been attributed to Dekker, Webster, Shakespeare and, most often, to Ben Jonson. Craig and Kinney found sufficient similarities in the frequency of common function words and of simple lexical words between the Additions to The Spanish Tragedy and the Shakespeare canon to come to the carefully-stated conclusion that the “readiest explanation” was that Shakespeare was the author of the Additions. But in his book on Kyd, Lucas Erne calls the attribution of the Additions to Shakespeare “groundless” (Beyond the Spanish Tragedy: A Study of the Works of Thomas Kyd 2001). What a shame that Craig and Kinney didn’t test the rest of the play! There are plenty of questions about its author, and the attribution to Kyd rests on shaky grounds. The senior Ogburns attributed an early version of it to Oxford, with Kyd assigned to finish it. More recently, several scholars, especially C.V. Berney, have adduced substantial evidence that it is a Shakespeare play.

Sir Thomas More

Craig and Kinney tested the approximately 1200 words in Additions II (Hand D) and III (Hand C) in the manuscript of Sir Thomas More against texts from the Shakespeare canon, as well as those by other dramatists, such as Dekker, Jonson and Webster. The results were clearly consistent with Shakespeare’s authorship of these additions, and no one else’s. This leads the authors to conclude that “the threshold from conjecture to genuine probability has been crossed.” They assert that this “creates a presumption in favour” of the proposition that the handwriting of Hands C and D is the same as that in the six extant signatures of Shakespeare of Stratford, and that this is now “among the surest facts of his biography.” Although these conclusions are not unusual, they contradict those of Elliott and Valenza, who applied their “new optics methodology” to the Hand D portion of Sir Thomas More and published their results in an article earlier this year. They concluded that it belonged “more in the high Apocrypha than in the Canon.” Indeed, Arthur Kinney himself wrote ten years ago that “the author of Addition II shares nothing whatever poetically with Shakespeare.”

Shakespeare, Co-Author?

In one chapter, Craig and Kinney report the results of their tests of the claims of Sir Brian Vickers in Shakespeare, Co-Author (2002) that four plays in the canon — Titus Andronicus, Timon of Athens, Henry VIII, and The Two Noble Kinsmen — are products of collaboration between Shakespeare and George Peele (Titus), Thomas Middleton (Timon), and John Fletcher (H8 and TNK). They consider these particular authorship questions “a convenient series of problems where the solution is known to a degree of certainty.” But they apparently tested only for the similarity in the use of function words by Shakespeare and the alleged co-author. They report the following results:

- Tests of the five longest scenes in Titus Andronicus indicate that Peele wrote the long opening scene, and Shakespeare the other four, as asserted by Vickers. But according to the scatter plot for these scenes, the score for the “Peele” scene is no farther from the Shakespeare centroid than the scores for several dozen text segments from undisputed Shakespeare plays. The remaining eight scenes, three of which Vickers attributed to Peele, are too short to be tested. Scholarly opinions about the percentage of Titus attributable to Shakespeare range from zero to 100%. In the most recent Arden edition, Jonathan Bate declared that “the whole of Titus is by a single hand” and that hand is Shakespeare’s. He based his opinion on a stylometric analysis by A.Q. Morton, who commented that the probability that Peele wrote any part of Titus was “less than one in ten thousand million.” Although he is noted for his habit of borrowing from other writers, there is no record of Peele ever collaborating with anyone.

- Tests of the four longest scenes in Timon of Athens indicate that Middleton wrote the second scene, and Shakespeare the other three, as claimed by Vickers. But again, the score for the “Middleton” scene is no farther from the Shakespeare centroid than scores for some text segments from undisputed Shakespeare plays. At least one score for a Shakespeare text block (Romeo and Juliet 1.2.6 to 1.4.46) “placed well into Middleton territory.” Here again, the evidence suggests divided authorship, but does not exclude Shakespeare’s authorship of the entire play. Most modern studies of the play divide it between Shakespeare and Middleton, but E.K. Chambers and Una Ellis-Fermor regarded it as entirely Shakespeare’s, but unfinished.

- Tests of six scenes in Henry VIII indicate that John Fletcher wrote 3.1 and 5.2, and Shakespeare the other four, as claimed by Vickers. Again, scores for the two “Fletcher” scenes were no farther from the Shakespeare centroid than scores for more than a dozen text blocks from canonical Shakespeare plays. As with Timon and Titus, the tests do not exclude Shakespeare’s authorship of the entire play.

- Scores for tests of two scenes in The Two Noble Kinsmen attributed by Vickers to Fletcher (2.2, 3.6), and one assigned to Shakespeare (1.1) all fell within the cluster for the author predicted. But, as before, neither of the scores for the two “Fletcher” scenes deviated as far from the Shakespeare centroid as did more than a dozen scores for blocks of genuine Shakespeare text. Nor was the score for the Shakespeare scene farther from the Fletcher centroid than numerous scores for scenes from plays by Fletcher alone.

These results are suggestive of co-authorship, but they should be considered in the context of similar results in the undisputed portion of the canon. Using data obtained about his use of function words from the entire “core” of 27 Shakespeare plays, Craig and Kinney compared them to 62 segments of 2000 words each in six individual Shakespeare plays and 55 such segments from six other plays reliably attributed to five other authors — all twelve plays chosen at random. Of the 62 authentic Shakespeare segments tested, only 50 were correctly classified as Shakespeare’s work. (For instance, four of the eight segments tested in A Midsummer Night’s Dream and three of the seven in Love’s Labor’s Lost were classified as “non-Shakespearean.”) Of the 55 non-Shakespearean segments tested, seven were not attributed to the correct author. Thus, the success rate for these segments was 87%, and for the Shakespeare plays it was only 81%. A testing method that is incorrect by its own standards 13% to 19% of the time may be termed suggestive, but hardly definitive.

[pullquote]In the face of such shortcomings, what is one to think? An obvious explanation is that orthodox scholars are groping blindly in the wrong paradigm, handicapped by the confines of the conventional Shakespearean dating system.[/pullquote]In the face of such methodological shortcomings, conflicting opinions, and dueling analyses, what is one to think? An obvious explanation is that today’s orthodox scholars, including all the stylometricians here mentioned, are groping blindly in the wrong paradigm, and are thus handicapped by the confines of the conventional Shakespearean dating system. (Craig and Kinney are familiar with the Oxfordian argument, and mention it several times, once even citing an article in The Oxfordian.) In addition, very few scholars of any period have given any consideration to the idea of a substantial corpus of Shakespearean juvenilia. We can be sure that Shakespeare did not always write like Shakespeare.

For those who find the evidence for Oxford as Shakespeare to be broader, stronger, and more reasonable than the Stratford theory, the case for co-authorship is very weak. Even if we accept the orthodox dating of these plays, none of the alleged collaborators was a likely partner for the mature Oxford, who had been entertaining the Queen and her court for as long as 25 years.

John Fletcher, for instance, was born in 1579 and, according to his entry in the DNB, did not begin writing plays until 1606, two years after Oxford died. And what sense does it make for the 50-year-old Oxford, with more than 30 plays to his credit (many of them masterpieces), to collaborate with Thomas Middleton, an unknown writer in his early 20s who wrote his first play, a collaboration, in 1602? Why would Oxford allow a mediocre playwright like George Peele to write the long opening scene in Titus Andronicus, in which are introduced all the important characters in one of his most personal plays?

As modern research has demonstrated, Shakespeare was a meticulous and persistent reviser of virtually all his plays over the course of a long career. But the jumbled condition of his printed works, many of which exist in two or more versions, reveals a patchwork of incompletely incorporated additions and deletions, as well as numerous inconsistencies, misnamings, and misalignments. There are several instances where the original passage remains in the text alongside the revision. It is much more likely that the substandard scenes that are attributed to co-authors are his original versions that, by chance or by compositor’s error, remained in the play after he revised the rest of it. The difference in the quality of writing is probably due to the development and refinement of his poetic and dramatic skills. Moreover, if he did collaborate with anyone, it would more likely have been with the playwrights in his employ, John Lyly and Anthony Munday. Or perhaps his son-in-law, the courtier-poet William Stanley, who in 1599 was reported to be writing “comedies for the common players.”

[pullquote]it seems clear that linguistic analysis by computer can never be more than a portion of the evidence.[/pullquote]Craig and Kinney and their fellow practitioners of stylistics, stylometry, etc. may have reached the limit of linguistic analysis by computer. Despite their confidence that their method can safely identify the work of an individual author, it seems clear that linguistic analysis by computer can never be more than a portion of the evidence needed to do so. External evidence, topical references, and the circumstances and personal experiences of the supposed author will remain important factors in any question of authorship. The noted economist, John Maynard Keynes, who was a scholarship winner in mathematics and classics at Cambridge and the author of a dissertation on probability, is said to have remarked that he was “not prepared to sacrifice realism to mathematics.” We would do well to follow his example.

Ramon Jiménez is the author of Shakespeare’s Apprenticeship: Identifying the Real Playwright’s Earliest Works (2018) (published by McFarland and also available on Amazon), a landmark study of several early Shakespeare plays and their revolutionary implications for the authorship question. He has also written two acclaimed histories of ancient Rome, both book club selections — Caesar Against the Celts (Da Capo, 1996) and Caesar Against Rome: The Great Roman Civil War (Praeger, 2000) — as well as several important articles including “The Case for Oxford Revisited” (2009), “Ten Eyewitnesses Who Saw Nothing: Shakespeare in Stratford and London” (2011), and “An Evening at the Cockpit: Further Evidence of an Early Date for Henry V” (2016), showing that Shakespeare’s Henry V was probably written and performed no later than 1584. In 2020 he published an important new article updating his work on Shakespeare’s early writings.

Ramon’s scholarly articles have appeared in The Oxfordian, the Shakespeare Oxford Newsletter, and in the anthology Shakespeare Beyond Doubt? (Shahan & Waugh eds. 2013). He and his wife, Joan Leon, are both former Trustees of the SOF and were jointly honored as Oxfordians of the Year in 2018. Ramon has also received the Award for Distinguished Shakespearean Scholarship at the Shakespeare Authorship Studies Conference at Concordia University in Portland, Oregon.

[published Dec. 24, 2019, updated 2021]

Membership dues cover only a fraction of our budget, including all our research, preservation and programming. Please support the SOF by making a gift today!

Blue Boar Tavern: Wassail Q&A

Tuesday Dec. 17, 8pm E / 5pm P

Sign up below for event invites!