“What’s in (the Spelling of) a Name?”

by Bryan H. Wildenthal

August 9, 2018

What’s in a name? Perhaps, as Juliet recognized, not much (see Romeo and Juliet, act 2, sc. 2).

The differences in spelling between “Shakespeare,” “Shakspere,” and their variants do not in themselves, in my opinion, provide the strongest argument for authorship doubt. There are many stronger ones. The late Oxfordian scholar Peter Moore (one of our best) went too far in calling the spelling issue a “zero argument.” But I do agree with Moore — and to some extent with David Kathman, a Stratfordian scholar — that some non-Stratfordians, on some occasions, may place too much emphasis on the spelling of the names.2

However, as this article seeks to show, the spelling issues do in fact raise very interesting questions as part of the broader Shakespeare Authorship Question (SAQ). They add to the background evidence suggesting early doubts about the identity of the author “Shakespeare,” the subject of my 2017 conference presentation and 2019 book (see endnote 1).

Everyone agrees that spelling was highly variable in early modern England. Stratfordians sometimes suggest on that basis, quite mistakenly, that the spelling of names had no significance at all. Yet we know that Ben Jonson, another great poet-playwright of the time, was very particular and consistent about the spelling of his own name. He “deliberately and publicly dropped the ‘h’ from his family name to distinguish himself …” (Pointon 2011, 19). Jonson’s two leading biographers (both Stratfordians) have discussed this (Riggs, 114–15; Donaldson, 56). Yet neither they nor any orthodox writers, to my knowledge, have ever conceded the obvious significance this has for how we might interpret the spellings of “Shakspere,” “Shakespeare,” and their variants.

Jonson’s new spelling, adopted midway through his literary career, “was not a casual aberration: [He] would employ it in his printed works and private correspondence for the rest of his life. Names meant a great deal to Jonson.” (Riggs, 114, emphasis added; see also Price, 66, quoting and discussing more extensively this passage by Riggs.) Perhaps most tellingly, in speculating why Jonson adopted the new spelling, Riggs noted that it “was an invented name that implied autonomy” (115, emphasis added).

This all raises obvious questions. Why should we assume, as Stratfordians do, that the variant spellings of Shakespeare are just “casual aberrations”? Why should we assume the spelling of that author’s name (or pseudonym) did not also “mean a great deal” to him? Does the highly consistent spelling of the published name — notably different from how William Shakspere of Stratford-upon-Avon and his family spelled their name in many important personal records — suggest it too “was an invented name”? If so, invented by whom and for what purpose? Unlike Jonson, Shakspere does not appear to have consistently conformed his name’s spelling in personal matters to that of the published name.

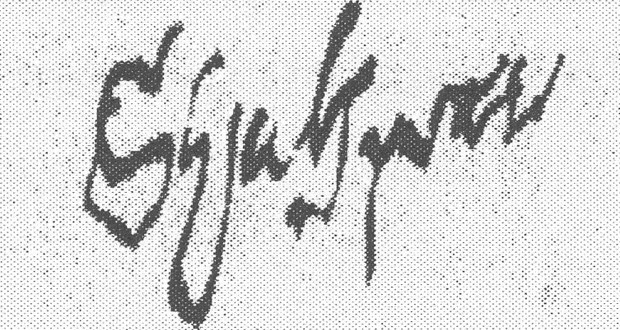

Because the Stratford man’s name appears consistently as “Shakspere” in his birth and death records, because that spelling or close variants appear in almost all other vital family records (and so far as can be made out, in his almost illegible purported signatures), all of which seem likely to reflect his and his family’s preferences — and because no documentary evidence during his lifetime clearly links him to the literary works published under a name almost uniformly spelled “Shakespeare” (sometimes hyphenated) — it is amply justified for convenience and clarity to render his name consistently as “Shakspere.”3

Using this well-documented historical spelling of the Stratford man’s name has the key benefit — especially when discussing the SAQ — of clarifying whether one is referring specifically to the businessman (and apparent sometime actor) from Stratford or the author “Shakespeare” (whoever that was). It does not unfairly prejudge the authorship issue. It is plausible, viewed in isolation (while raising obvious questions as noted), that a man from Stratford named “Shakspere” might have written poems and plays that, for some reason, were published under a name consistently spelled “Shakespeare.” Whether that is actually or likely what happened depends mainly on other available evidence, quite apart from the spelling issues.

Orthodox Scholars Alter Spellings, Ignore Patterns, and Seek to Rewrite or Erase History

Moreover, some orthodox scholars have proven quite unreliable on the issue of spelling. Stratfordians today seem to want to rewrite history by harmonizing the spelling in all cases as “Shakespeare.” An especially egregious example of fitting facts to theory — of literally erasing an inconvenient historical fact — was when Kathman revised the first name of Shakspere’s grandson to “Shakespeare.” He even put it in quotation marks! The child was actually baptized “Shaksper” Quiney in honor of his recently deceased grandfather, and upon his death six months later was buried as “Shakspere.”4

Professor James Shapiro has falsely claimed that “[t]here’s no pattern” to the spelling of the author’s published name and that it was sometimes published as “Shakspere” (2010, 227). These two falsehoods are among many erroneous, misleading, or tendentious statements in his 2010 book.5 With unintended irony, Shapiro added (2010, 227): “Shakespeare himself [he meant Shakspere of Stratford] didn’t even spell his own name the same way.” Indeed! But the author “Shakespeare” very consistently did.

No less ardent a Stratfordian than Kathman, whose relevant article was prominently available on the internet when Shapiro wrote, may be cited to debunk Shapiro on the spelling of the author’s published name. Indeed, Shapiro hailed with approval the website on which Kathman’s article appears. Among 138 published “literary” references, as catalogued and counted by Kathman, 131 (95%) spell the name “Shakespeare” (hyphenated “Shake-speare” in 21 of those 131 references). Published references to “Shakspere” or “Shaksper” according to Kathman: Zero.6

Not coincidentally, most authorship doubters suspect, this effort to falsify the historical record conveniently reinforces the Stratfordian theory. It does so, in part, by making it difficult even to discuss the SAQ lucidly. This may readily be seen, for example, when orthodox advocates retreat behind mind-numbingly circular mantras like “Shakespeare Wrote Shakespeare.”7 Embarrassingly for present-day Stratfordians, however, orthodox scholars during the 19th and early 20th centuries frequently referred to “Shakspere” (see Pointon 2011, 17–18; Pointon, “Man Who Was Never Shakespeare,” 2013, 21–22). We can only feel nostalgia for the good old days when Stratfordians were a bit more candid and a bit more attentive to historical realities.

It is hypocritical of Stratfordians to criticize non-Stratfordians (as they often do) for sometimes overemphasizing the spelling issues. Orthodox writers themselves place heavy emphasis on the purported identity of the Stratfordian and authorial names, while often (as noted) erasing and rewriting the historical record by harmonizing the spellings to fit their theory. The supposed identity of the names is often the very first point asserted in orthodox arguments.8

One cannot help but recall the goal of “Newspeak” in George Orwell’s 1984 — to make it difficult (even literally impossible) to articulate or even think unorthodox thoughts (see Orwell, 5 & n. 1, and 312–26). As Orwell commented (324), when Newspeak finally triumphed, “[w]hen Oldspeak [standard English] had been once and for all superseded, the last link with the past would have been severed.” In a similar way, some Stratfordians seem determined to sever the last links to the historical reality of early authorship doubts.

“History had already been rewritten,” Orwell went on (324) — just as the First Folio began rewriting the history of the SAQ as early as 1623 — “but fragments of the literature of the past survived here and there, imperfectly censored, and so long as one retained one’s knowledge of Oldspeak it was possible to read them. In the future, such fragments, even if they chanced to survive, would be unintelligible and untranslatable.”

Orwell commented (324–25) that no older book “could be translated [into Newspeak] as a whole. Pre-revolutionary literature could only be subjected to ideological translation—that is, alteration in sense as well as language.” In a comparable way, altering and suppressing the spelling of “Shakspere” of Stratford is far more than some technical adjustment to be defended on grounds of simplicity or clarity. It alters the very sense of the SAQ. It rewrites history.

As Orwell finally noted (325, emphasis added): “A good deal of the literature of the past was, indeed, already being transformed …. Various writers, such as Shakespeare … were therefore in process of translation: when the task had been completed, their original writings, with all else that survived of the literature of the past, would be destroyed.”

Anti-Stratfordians are determined that the true author of the works of “Shakespeare” (whoever that was) shall not meet the same fate of historical oblivion. His name shall not remain buried where his body lies.

Pseudonyms and Frontmen: Clues and Coincidences

Another instance of Stratfordian hypocrisy is that orthodox writers seem unfazed by the compelling circumstantial evidence supporting Edward de Vere (Earl of Oxford) as the true author (see, e.g., “Poetic Justice for the True Shakespeare?“). To the very limited extent they even bother to pay attention to the evidence, they apparently view the numerous connections between the Shakespeare canon and Vere’s life and known writings as random and meaningless — even though that implies an extraordinary (if not unbelievable) array of coincidences.

Yet Stratfordians reject as unthinkable the idea that a man from that town who became involved in the London theatre scene just happened coincidentally to have a name the same (or similar) as a pseudonym used by the author of published poems and plays. Stratfordians think they must therefore have been the same person. Curiously, many Oxfordians and other doubters also find it unbearably implausible that this could be purely coincidental, though for them that points to some consciously planned “frontman” scenario.

If Shakspere of Stratford was a frontman for a hidden author, then of course the similarity of the names was not coincidental. As an apparent investor and sometime actor conveniently placed in the theatre business, he may have regularly brokered and procured plays. He may have been ideally situated to be hired (or simply used) to pass off certain plays as his own. Doubters have long mulled over various possible scenarios. Obviously these are speculative, but they are also perfectly plausible in light of the limited known evidence. (Little if any of the following speculation is original to me; these possible scenarios have been discussed by innumerable writers for a long time.)

Perhaps there was no direct or active coordination between Shakspere and a hidden author. Perhaps, at most, he was paid to just keep quiet and go along with the possible confusion of his name with the author’s pseudonym. Perhaps he did not even need to be paid to go along. If a hidden author were powerful and well-connected, veiled threats might well have sufficed. And Shakspere may have found ways to profit from the plays on his own, even without being directly paid by an author. Indeed, perhaps it went the other way. Perhaps he paid the author for what may have been a lucrative business opportunity.

Perhaps it was indeed merely a coincidence involving similar names. Perhaps the pseudonym was independently chosen before Shakspere got involved — if he ever did, directly. Is that really so hard to believe? Katherine Chiljan has correctly questioned (34) why it should be “beyond … comprehension that there could have been two separate people with similar names that had theatrical interest, just like there were two men named John Davies who published poetry and were contemporaries.”

Chiljan referred to John Davies of Hereford (c. 1565–1618) and Sir John Davies, MP (1569–1626). Note also the occasional confusion between the scholar Laurence Nowell (c. 1515–c. 1571), Vere’s childhood tutor, and the clergyman Laurence Nowell (?–1576), Dean of Lichfield Cathedral (see Green, “Oxmyths and Stratmyths,” Sec. I, p. 7, and relevant Wikipedia articles). While “John Davies” was probably a more common name than “William Shakespeare,” even with all the latter’s variants, it seems quite possible that “Laurence Nowell” was more rare.

Stratfordian scholars have confirmed that “Shakspere,” “Shakespeare,” and their variants were actually not especially rare English family names at the time (see, e.g., Schoenbaum, 12–13). And William or “Will” was a very common given name, even more so then than now. Apparently more than one fifth of all Englishmen, 22%, during Shakespeare’s time, went by “William” or its variants (see Grazia, 111 n. 56, citing Ramsey, 23). That would make the combination very convenient and attractive as a pseudonym, quite aside from the obvious appeal of the vivid action conveyed by the surname. When you think about it, even conceding that plenty of real people had this name, “Shakespeare” just sounds an awful lot like a pen name, doesn’t it?

The leading biographer of Shakspere of Stratford actually observed (Schoenbaum, 13, emphasis added) — in reference to apparently unrelated persons sharing the name Shakespeare or its variants — that “the coincidence, while curious, need not startle us.” So why are Stratfordians like that biographer so startled by this possible coincidence?

“First Heir of My Invention”: Another Pseudonym Clue?

Chiljan, in a lecture summarizing her thinking on the matter (“Pen Name,” 2015; see also Chiljan, 27-31), discussed the many literary allusions to spear-shaking, in one form or another, leading up to 1593 when Venus and Adonis became the first publication to appear under the “Shakespeare” brand. Speaking of “invented names,” as discussed earlier, Chiljan reminded us that the author’s own dedication of that confident masterwork — how absurd to think it was really the “first” thing he wrote — described it as “the first heir of my invention.” This is not the only instance in which early authorship doubts appear to be hiding in plain sight.

Terry Ross (“Oxfordian Myths: First Heir”) attacks the idea that this phrase in the 1593 dedication suggests a pseudonym. His two key points are valid in themselves but do not support his conclusion. His first point — that “heir” reflects typical references by Elizabethan writers to their works as children — is puzzlingly irrelevant and actually synergizes perfectly with the anti-Stratfordian reading. His second point, that “invention” was commonly used (including by Shakespeare; Ross gives four examples) to mean a writer’s “creativity” or “imagination,” is perfectly consistent with it also being used here to suggest a pseudonym, especially one newly created or receiving its public debut.

Ross claims “no instances” in the Oxford English Dictionary (OED) where “invention” means “pseudonym.” But even leaving aside Shakespeare’s innovative use of language (of which this might be an example), Ross misses several OED definitions supporting the anti-Stratfordian reading. To be sure, two definitions of “invention” (3.b and 4) reflect his preferred reading (artistic creativity), which was likely the intended plausible surface meaning; and the OED definitions do not explicitly cite the word “pseudonym.” But definition 2 equates “invention” with “[t]he action of … contriving, or making up; contrivance, fabrication”; definition 6 (under heading II, a “thing invented”) is “[s]omething devised; a method of action … contrived by the mind; a device, contrivance, design, plan, scheme”; definition 8 a “fictitious statement or … fabrication”; and definition 9 “an instrument … originated by the ingenuity of some person.”

The latter four definitions are supported by 16th-century illustrations, including two by Shakespeare (OED, v. 8, 40). See Henry VI, Part 3, act 4, sc. 1: (“[King Edward:] What if both Lewis and Warwick be appeased By such invention as I can devise?”); All’s Well That Ends Well, act 3, sc. 6 (“[Bertram:] [W]ill [Parolles] make no deed at all of this that so seriously he does address himself unto?” [French Lord:] None in the world; but return with an invention, and clap upon you two or three probable lies.”).

Supporting the idea of “invention” as the debut of a pseudonym (or “contrivance,” “fabrication,” etc.) are two definitions obsolete today but supported by 17th-century illustrations: 10 (“[s]omething formally or authoritatively introduced or established”) and 12 (“[c]oming in, arrival”) (OED, v. 8, 40, emphasis added). Keep in mind the context of the overall phrase: “the first heir of my invention.” Ross thrice reiterates the importance of “context.”

What makes Ross’s dismissal of the anti-Stratfordian reading quite insufferable, given that he himself ignores the historical and contextual definitions above, is his patronizing scolding about the importance of considering historical context (“Oxfordian Myths: First Heir,” emphasis added): “[T]he language of Elizabethan dedications is very foreign to modern readers, and it is often dangerous to interpret such language in [modern] terms …. [W]e must look at the Elizabethan concept of ‘invention’ before we can understand Shakespeare’s phrase.” Yes indeed, “we must”! The only “danger” here is to Stratfordian orthodoxy.

Surely Ross is joking (or has an overly literal mind) when he suggests that if the “author had circulated Venus and Adonis under any name but his own [or anonymously], he would not have referred to it as an ‘heir.’ … [Rather], it would more properly have been labeled a bastard ….” Really? In a graceful dedication to a nobleman written as if by a fawning commoner? Ross asserts: “Far from … signal[ing] … a pseudonym, the dedication … amounts to a virtual warranty that the work bears its author’s actual name.” But don’t writers using pen names often want them to be convincing or at least plausible at some level?

Conclusion

Perhaps theatrical and literary insiders knew perfectly well that Shakspere was no poet or playwright (one can imagine them rolling their eyes) and that “Shakespeare” was a pseudonym for someone who really was.9 Just because we obsess over the similarity of the names doesn’t mean Elizabethans did. They may have shrugged indifferently at the nominal linkage. Perhaps they joked about it. Or perhaps they knew it was better not to talk about it, much less put anything in writing about it.

Perhaps many people did not know the identity hidden behind the pseudonym. Perhaps most just didn’t give a damn. Perhaps many people outside literary and theatrical circles, not personally acquainted with Shakspere or the true author, drew their own mistaken conclusions. Perhaps over time such confusion was encouraged and eventually suggested a more systematic merger of identities, which obviously would have become easier after Shakspere died.10

Did Shakspere of Stratford care as much as Ben Jonson about how his name was spelled? The truth is, we may never know. But we do have some clues about how the author “Shakespeare” may have felt. He seemed very focused on the significance of names. Juliet’s famous question expressed her desire to transcend the strictures of names but also lamented the reality, as she knew all too well, that names matter very much.

The author repeatedly tells us that his true name is hidden and may never be known. I paraphrased above one of his lines to that effect, to which Stratfordians should pay more attention: “My name be buried where my body is …” (Sonnet 72, ln. 11). Yet, he also teased us, “every word doth almost tell my name” (Sonnet 76, line 7).

Endnotes (see Bibliography below for full source information and hot-links)

1 Bryan H. Wildenthal is Professor of Law Emeritus and former SOF Trustee; A.B., J.D., Stanford University.

This article is dedicated to my beloved husband Ashish, who so generously supports all my endeavors. The article is copyright 2018 by Bryan H. Wildenthal and the Shakespeare Oxford Fellowship. Permission granted to copy and distribute it (in whole or in part) for any nonprofit personal or educational use, on condition that all references and copies credit the author and provide an acknowledgment and link to this publication on the SOF website. All photographs in this article are in the public domain.

This article is dedicated to my beloved husband Ashish, who so generously supports all my endeavors. The article is copyright 2018 by Bryan H. Wildenthal and the Shakespeare Oxford Fellowship. Permission granted to copy and distribute it (in whole or in part) for any nonprofit personal or educational use, on condition that all references and copies credit the author and provide an acknowledgment and link to this publication on the SOF website. All photographs in this article are in the public domain.

A PDF version of this article is available here on SSRN (if prompted to create an account, “download without registration” at right). The article also appears in somewhat different form as Part III.A of my book Early Shakespeare Authorship Doubts (2019). Free excerpts of the book are available here on SSRN; full hardcover version available here; full paperback here; also here on Amazon. Most of my scholarly writings relating to law or Shakespeare (some relate to both) are available here on SSRN. I am also the author of a textbook on law and history (Native American Sovereignty on Trial, 2003) and numerous articles in leading law reviews (mainly on constitutional law and history), including one on the Civil War-era 14th Amendment to the U.S. Constitution cited in an opinion of the U.S. Supreme Court, two concurring opinions, and numerous briefs on both sides, in major decisions by the Court in 2010 (McDonald v. Chicago) and 2019 (Timbs v. Indiana).

2 See Moore (1996); Kathman, “Shakespeare Wrote Shakespeare” (2009), 15; see also Kathman, “Spelling.” For a cogent response to Kathman, see Whalen (2015) (with which I generally agree). Moore’s contributions to scholarship are reflected in The Lame Storyteller, Poor and Despised, the 2009 collection of his articles edited by Gary Goldstein.

3 On his and his family’s apparent spelling preferences, see Pointon (2011), 17, 24; see also 11-24; Pointon, “Man Who Was Never Shakespeare” (2013); Jolly. On his signatures, see Davis. On the lack of documentary evidence during Shakspere of Stratford’s lifetime clearly and personally linking him to the literary works of “Shakespeare,” see, e.g., the notable concession by the leading and vociferously Stratfordian scholar Stanley Wells, in his 2013 essay “Allusions,” 81. See also Shahan & Waugh, ch. 3, 41–45 (summarizing Diana Price’s findings); see generally Price.

4 Compare Kathman, “Shakespeare and Warwickshire” (2013), 125, with Shahan & Waugh, 13 (and ii-iii, discussing a similar alteration of the record in Wells, “Allusions,” 81, again with deceptive quotation marks).

5 Another (less important) goof for which Shapiro richly deserves the ridicule he has already received from many doubters — given his purported expert status, his pompous dismissal of skeptics, and because it’s the kind of blooper for which we suspect he might mark off an undergraduate for not reading the source carefully — was his erroneous claim (deployed to criticize the focus of some doubters on the hyphenation issue) that “Shakespeare” was hyphenated in the dedications of Venus and Adonis and The Rape of Lucrece. See Shapiro (2010), 225.

6 Kathman, “Spelling.” Among 33 handwritten references (rather broadly and debatably defined as “literary” by Kathman), it was spelled “Shakspere” or “Shaksper” only once each (second 1593 and sixth 1609 references in Kathman’s list), in notes jotted down by purchasers (respectively) of Venus and Adonis (1593) and the Sonnets (1609). According to Kathman, by far the most common handwritten “literary” spelling (12 of 33 references, 36%) was “Shakespeare” and 18 of those 33 (55%) were consistent with the latter in using the medial “e” (notably distinct from “Shakspere” and its variants in that regard). See Kathman, “Spelling”; Kathman, “Chronological.” One would expect, of course, more variability in handwritten records. Shapiro (2010), 281, praised the Kathman & Ross website on which these articles appeared as providing “a point-by-point defense of Shakespeare’s authorship.” He did not notice that they provide a point-by-point refutation of his own comment about the alleged lack of pattern to the published spelling of Shakespeare’s name.

7 E.g., Kathman, “Shakespeare Wrote Shakespeare” (2009); Reedy & Kathman, “How We Know That Shakespeare Wrote Shakespeare”; Wells, “Allusions,” 87 (claiming that “[t]he evidence that Shakespeare wrote Shakespeare is overwhelming”). For a rebuttal of Reedy & Kathman, see Kositsky & Stritmatter (2004).

8 See, e.g., Kathman, “Shakespeare Wrote Shakespeare” (2009), 14-15 (“The Name”); Reedy & Kathman (heading 1, “The Name ‘William Shakespeare’ Appears on the Plays and Poems,” followed by headings 2–5 asserting that “William Shakespeare” was an actor and theatre shareholder from Stratford and author of the plays and poems).

9 A pseudonym that makes intended use of the actual name of another real person may be described by the obscure term “allonym.” OED, v. 1, 341. Some Shakespeare authorship doubters get tetchy about this and suggest it is a mistake to use the term “pseudonym” at all — which is not just wrong but silly. An allonym, by definition, is a pseudonym — a subset or specific example of the latter. A pseudonym does not imply only a fictitious or invented name, but rather encompasses any “false or fictitious name.” OED, v. 12, 751. The “allonymic” theory is generally the assumed, most familiar, and dominant paradigm in the SAQ. Thus, one could frame the issue in text as whether the Shakespeare “pseudonym” is or is not also an “allonym.” But I fear deploying rare vocabulary may be more confusing than helpful.

10 There are admittedly a lot of “perhapses” in the main text above, which simply reflects how much we do not (and may never) know. Stratfordian “biographies” are filled with much more speculation—often much less plausible. See, e.g., the largely fictional and speculative “biographies” by Greenblatt (2004) and Ackroyd (2005). For two excellent analyses of the fictional Shakespeare biography phenomenon, see Ellis (2012) and Gilvary (2018).

Bibliography

Ackroyd, Peter, Shakespeare: The Biography (2005).

Anderson, Mark, “Shakespeare” By Another Name: The Life of Edward de Vere, Earl of Oxford, the Man Who Was Shakespeare (2005).

Booth, Stephen, ed., Shakespeare’s Sonnets (1977, rev. 1978, pap. ed. 2000).

Chiljan, Katherine, Shakespeare Suppressed: The Uncensored Truth About Shakespeare and His Works (2011, rev. 2016) (cited as “Chiljan”).

_____, “Origins of the Pen Name ‘William Shakespeare’ ” (Shakespeare Oxford Fellowship Conference Presentation, Sept. 26, 2015) (posted on YouTube Dec. 13, 2015).

Davis, Frank, “Shakspere’s Six Accepted Signatures,” in Shahan & Waugh (2013), ch. 2, 29.

Donaldson, Ian, Ben Jonson: A Life (2011).

Edmondson, Paul & Stanley Wells, eds., Shakespeare Beyond Doubt: Evidence, Argument, Controversy (2013).

Ellis, David, The Truth About William Shakespeare: Fact, Fiction and Modern Biographies (2012).

Gilvary, Kevin, The Fictional Lives of Shakespeare (2018).

Grazia, Margreta de, “The Scandal of Shakespeare’s Sonnets,” in Schiffer (1999), 89 (orig. pub. Shakespeare Survey, v. 46, 1994, 35) (citations to 1999 reprint).

Green, Nina, The Oxford Authorship Site.

_____, “Oxmyths and Stratmyths” (Section I; Section II; Section III; Section IV), on Green, Oxford Authorship Site.

Greenblatt, Stephen, Will in the World: How Shakespeare Became Shakespeare (2004).

Jolly, Eddi [Margrethe], “Sc(e)acan, Shack, and Shakespeare,” Oxfordian, v. 18 (2016), 41.

Kathman, David, “Shakespeare Wrote Shakespeare,” Oxfordian, v. 11 (2009), 13.

_____, “Shakespeare and Warwickshire,” in Edmondson & Wells (2013), ch. 11, 121.

_____, “Chronological List of References to Shakespeare as Author/Poet/Playwright” (n.d.), on Kathman & Ross, Shakespeare Authorship Page.

_____, “The Spelling and Pronunciation of Shakespeare’s Name” (n.d.), on Kathman & Ross, Shakespeare Authorship Page.

Kathman, David & Tom Reedy. See Reedy & Kathman.

Kathman, David & Terry Ross, eds., The Shakespeare Authorship Page.

Kositsky, Lynne & Roger A. Stritmatter, “A Rebuttal to Tom Reedy and David Kathman’s ‘How We Know That Shakespeare Wrote Shakespeare’ ” (Sept. 12, 2004), on Shakespeare Oxford Fellowship.

Lee, Sidney, ed., Venus and Adonis, The Rape of Lucrece, The Passionate Pilgrim, Shake-speare’s Sonnets, and Pericles, Prince of Tyre (Oxford UP, 1905) (apparently a one-volume collection, identified on Google Books only as Venus and Adonis, but in fact containing facsimile reprints of each of the five named works, with extensive introductory editorial notes on each, separately and not sequentially paginated).

Moore, Peter R., “Recent Developments in the Case for Oxford as Shakespeare” (Shakespeare Oxford Society Conference Presentation, Oct. 1996), on Shakespeare Oxford Fellowship.

_____, The Lame Storyteller, Poor and Despised: Studies in Shakespeare (Gary Goldstein ed. 2009).

Orwell, George, 1984 (1949) (reprinted, Steven Devine illus., Folio Society, 2001) (citations to 2001 reprint).

The Oxford English Dictionary (20 vols., 2d ed. 1989) (OED).

“Poetic Justice for the True Shakespeare?” (June 22, 2018), on Shakespeare Oxford Fellowship.

Pointon, Anthony J., The Man Who Was Never Shakespeare: The Theft of William Shakspere’s Identity (2011).

_____, “The Man Who Was Never Shakespeare: The Spelling of William Shakspere’s Name,” in Shahan & Waugh (2013), ch. 1, 14.

Price, Diana, Shakespeare’s Unorthodox Biography: New Evidence of an Authorship Problem (2001, rev. 2012) (Shakespeare’s Unorthodox Biography is also the title of Price’s website, containing updates to the book and much valuable additional scholarly work and commentary).

Ramsey, Paul, The Fickle Glass: A Study of Shakespeare’s Sonnets (1979).

Reedy, Tom & David Kathman, “How We Know That Shakespeare Wrote Shakespeare: The Historical Facts” (n.d.), on Kathman & Ross, Shakespeare Authorship Page.

Riggs, David, Ben Jonson: A Life (1989).

Ross, Terry, “Oxfordian Myths: ‘First Heir of My Invention’ ” (n.d.), on Kathman & Ross, Shakespeare Authorship Page.

Ross, Terry & David Kathman. See Kathman & Ross.

Schiffer, James, ed., Shakespeare’s Sonnets: Critical Essays (1999).

Schoenbaum, Samuel, William Shakespeare: A Compact Documentary Life (1975, rev. 1987) (citations to 1987 abridged edition).

Shahan, John M. & Alexander Waugh, eds., Shakespeare Beyond Doubt? Exposing an Industry in Denial (2013).

Shakespeare Oxford Fellowship: Research and Discussion of the Shakespeare Authorship Question.

Shakespeare, William, Venus and Adonis (author designated not on title page but only following dedication) (London: Richard Field, 1593) (facsimile reprint in Lee 1905).

_____, Shake-speare’s Sonnets (author of Sonnets designated only in title, by surname, with blank space between two lines on title page where author’s name would normally appear, though “William Shake-speare” is designated as author of appended poem “A Lover’s Complaint”) (London: George Eld for Thomas Thorpe, 1609) (facsimile reprints in Lee 1905 and Booth 1977).

_____, William Shakespeare’s Comedies, Histories, and Tragedies [First Folio] (London: Isaac Jaggard & Edward Blount, 1623) (facsimile reprint in The First Folio of Shakespeare: The Norton Facsimile, Charlton Hinman & Peter W.M. Blayney eds., 2d ed. 1996).

Shapiro, James, Contested Will: Who Wrote Shakespeare? (2010).

Stritmatter, Roger A. & Lynne Kositsky. See Kositsky & Stritmatter.

Waugh, Alexander & John M. Shahan. See Shahan & Waugh.

Wells, Stanley, “Allusions to Shakespeare to 1642,” in Edmondson & Wells (2013), ch. 7, 73.

Wells, Stanley & Paul Edmondson. See Edmondson & Wells.

Whalen, Richard F., “Was ‘Shakspere’ Also a Spelling of ‘Shakespeare’? Strat Stats Fail to Prove It,” Brief Chronicles, v. 6 (2015), 33.

Wildenthal, Bryan H., “Remembering Rollett and Debunking Shapiro (Again)” (2016).

_____, “Early Shakespeare Authorship Doubts: Debunking the Central Stratfordian Claim” (Shakespeare Oxford Fellowship Conference Presentation, Oct. 14, 2017) (posted on YouTube Dec. 8, 2017).

_____, Early Shakespeare Authorship Doubts (2019).

[published Aug. 9, 2018, updated 2021]