“While counterfeit supposes bleared thine eyne …”

Intertextual Evidence for Shakspere as an Authorship Front Man

by Jonathan Dixon

Editorial Note: This article was originally published in Shakespeare Matters, vol. 4, no. 2 (Winter 2005), p. 12 (PDF version of that issue, including Dixon’s article, available here). It is republished here on the SOF website, December 10, 2018.

If in nothing else, anti-Stratfordians are unified in their belief that William Shakspere was not “William Shakespeare.” Yet uncertainty and disagreement exist over what was the Stratfordian’s role in the authorship question. Was he strictly a businessman with few theater connections who just happened to get confused with the authorship late in the day because of his similar name; or was he actually an actor and involved theater partner? Was he tied to the works of “Shakespeare” from the beginning, or did that connection begin in the 1600s, after the deaths of those directly involved? Was he a play-broker and middleman dealing in old and anonymous plays whose name was merely associated with the plays at first; or was he part of a deliberate deception, working with the true author as an actual “front man” and actively pretending to be the author himself?

Three works published within an approximately two-year period in the early 1590s suggest that the last scenario may have been the case: that Shakspere—by then in his late twenties and apparently a successful entrepreneur and theatrical jack-of-all-trades—may actually have been deliberately employed as a front-man for the hidden author of the Shakespeare works. Further, they suggest that there were rumors about this pretense, and that some who were in the know were offended by it.

Before looking at those three works, however, a prelude…

1584—Robert Greene’s The Mirror of Modesty

In his dedication to the Countess of Derby in The Mirror of Modesty, Robert Greene wrote:

your honor may think I play like Aesop’s Crow, which decked her self with others’ feathers or like the proud Poet Batillus, which subscribed his name to Virgil’s verses, and yet presented them to Augustus. (3:7)

In this passage Greene is referring to the story of the Roman actor Batillus: Caesar Augustus had expressed admiration for a certain anonymous poem and, hearing this, Batillus claimed to be the author. The true author was, in fact, Virgil, who exposed Batillus as a fraud.

By itself this passage means little. However, we should note that in it Greene is tying the image of Aesop’s crow to the historical Batillus’s practice of fraudulently passing himself off as the author of another’s work:1

Now to the first of those three works from the early 1590s:

1591—Robert Greene’s Farewell to Folly

Several years later Greene returned to “Batillus” in Farewell to Folly (originally registered in 1587, but published in 1591). In a letter addressed “to the Gentlemen Students of both Universities” he wrote:

Others will flout and over-read every line [of this pamphlet] with a frump, and say ‘tis scurvy, when they themselves are such scabbed Jades that they are like to die of the fashion, but if they come to write or publish anything in print, it is either distilled out of ballads or borrowed of Theological poets, which for their calling and gravity, being loathe to have any profane pamphlets pass under their hand, get some other Batillus to set his name to their verses: Thus is the ass made proud by this underhand brokery. And he that can not write true English without the help of clerks of parish churches will needs make himself the father of interludes. (9: 232-33)

Greene seems to be referring to a recurring pet peeve: plagiarists and people who take credit for others’ work.

In answer to Diana Price’s use of this quote as evidence supporting the hypothesis that William Shakspere was a front man, Stratfordians on the humanities.literature.authors.Shakespeare online forum have pointed out that the historical Batillus was actually a poet himself (although a bad one), and have argued that in this passage Greene was using “Batillus” to mean simply a “bad poet,” not a front man. They have produced examples of the name “Batillus” being used to describe a bad poet—including one in which Greene referred to himself as a “Batillus.” They argue that in this passage Greene is simply saying that some anonymous bad poets got other bad poets to take credit for their work. Furthermore, they claim triumphantly, since the original Batillus was himself a poet, for Oxfordians to refer to Shakspere as a “Batillus” is thus to acknowledge that Shakspere was indeed a poet. Also, countering Price’s use of the word “Batillus” to describe a “front man” or “agent,” they point out that the historical Batillus stole credit for Virgil’s verse; he was not employed as a front man.2

That is all more or less true. However, these orthodox critics are willfully ignoring the most dangerous point of this passage as it relates to the authorship debate: Whatever terminology Greene chose to use, in this passage he is explicitly describing the practice in his day of poets of dignity and rank who wished to remain anonymous to protect their reputations employing other people to take credit for their work.

Greene’s quote should be recognized as one of the most powerful pieces of evidence in the entire anti-Stratfordian case. It should be presented in any presentation on the authorship question because it provides positive proof—repeat—proof that in Elizabethan England front men were indeed employed, and possibly paid by, anonymous highly-placed writers for the use of their names. (Greene’s use of the word “brokery” suggests there was payment somehow involved—that it was a kind of business arrangement.) Further, it confirms that those writers took this course to protect their reputations. [pullquote]Greene’s quote should be recognized as one of the most powerful pieces of evidence in the entire anti-Stratfordian case … it provides positive proof … that in Elizabethan England front men were indeed employed…[/pullquote]

To reverse the direction of the argument for the sake of clarity: Greene tells us there were authorship front men used in his time. That being so, he chose to call them “Batilluses.” Whether the historical Batillus was himself a poet, good or bad, isn’t the point here. The point is that it was the writers who initiated the deception, who “got” the front-men. Unlike the historical Batillus, who initiated his own deception and was exposed, Greene’s modern-day “Batilluses” were actually employed by the anonymous writers whose work they took credit for. So, yes, while it is true that the original Batillus was not strictly a “front man,” Greene makes it clear that his modern “Batilluses” were.

Whether those modern-day fronts were also poets themselves, or could have been non-writers, is open to debate. Greene’s reference to a near-illiterate styling himself “the father of interludes” indicates they may not have been practicing writers.3 At any rate the parallels between the historical Batillus and these “Battiluses” aren’t as literal as Stratfordians would insist. Batillus was recognized as a bad poet, a plagiarist who incorporated pieces from others’ work into his own and as someone who had gone the extra step of blatantly taking full credit for a hidden author’s work.

Greene singled out “Theological poets” as those taking part in this practice, but he did not state they were the only ones to do so. While Greene’s passage does not provide proof that poets who were members of the nobility also employed fronts, it is reasonable to assume they might have done so.

That assumption is actually supported by the author of The Arte of English Poesie (1589), thought to be George Puttenham, who wrote:

Among the nobility or gentry as may be very well seen in many laudable sciences and especially in making poesy, it is so come to pass that they have no courage to write and if they have are loath to be known of their skill. So as I know very many notable gentlemen in the Court that have written commendably, and suppressed it again, or else suffered it to be published without their own names to it: as if it were a discredit for a gentleman to seem learned. [Sobran 134; emphasis added]

The phrasing “published without their own names to it”—rather than just “published without their names to it”—suggests these works were published not just anonymously, or with made-up pseudonyms, but with other people’s names to them.

So, while Greene’s quote may not be a smoking gun proving the Earl of Oxford was Shakespeare, it is a smoking gun proving that the basic Oxfordian hypothesis of an illustrious author taking a real-life front man to protect his reputation was, indeed, a genuine practice of the time. It renders moot all objections from Stratfordians that such an arrangement is incredible. While we may not know the details in the case of a “fronted” Shakespeare authorship—how Shakspere might have come into the picture, what part payment might have played, how much those around might have known, and so on—Oxfordians can no longer be attacked on the question of whether such real-life front men were used.

In fact, Greene opens up a whole new area of exploration in Elizabethan literature, for given what he tells us, the logical questions become: How widespread was this practice? Who exactly were those hidden poets of “calling and gravity”? What authors are not to this day getting the credit they deserve? And of the names we have on title pages, which were “fronts”? Which works were intentionally mis-attributed to protect an author’s reputation?

For scholars of Elizabethan literature to avoid these questions is, at best, a case of poor scholarship and, at worst, intellectual dishonesty, for given what Greene tells us, all printed names on title pages become suspect to some degree. The logical questions to propose are: Which names on title pages seemed to be most questioned and doubted? Which writers most have a reputation for “borrowing”? Around which authors did there seem to be authorship-related rumors? Which personages who fit the description “of calling and gravity” were rumored or reported as having published anonymously?4

The most notable answer to these questions is “Shakespeare.” On this point it is worth noting what Diana Price points out in Shakespeare’s Unorthodox Biography:

- In 1595, in Polimanteia, a writer “W.C.” indicated his belief that “Shakespeare” was Samuel Daniel by praising Shakespeare and some of his poems and characters in a note beside a passage about Daniel (225).

- In satires published in 1598—and subsequently ordered burned by the Archbishop of Canterbury in 1599—Joseph Hall and John Marston implied that Venus and Adonis was by Francis Bacon (225; also Michell, 126-129).

- In 1599 the authors of the Parnassus plays attributed a quote from Romeo and Juliet to Samuel Daniel—even though that attribution occurs in an exchange in which the name “Shakespeare” is mentioned two lines earlier, and even though Romeo and Juliet had been attributed to Shakespeare a year earlier by Meres, and in that same year by Weever (84).

- Sometime between 1598 and 1601 Gabriel Harvey expressed his belief that “Shakespeare” was Sir Edward Dyer (225). (see note 10 below.)

These examples prove that from 1595 to 1599, at the very least, there was a belief in the Elizabethan literary world that the authorial name “William Shakespeare” did not refer to a real person. They also prove that there was confusion and acknowledged mystery around the authorship of Shakespeare’s works.

Historically, Stratfordians and anti-Stratfordians alike have claimed that doubts about the authorship did not begin until hundreds of years after Shakespeare’s time. That dating is not correct. The above examples make it clear that the Shakespeare authorship mystery began during Shakespeare’s lifetime, even as the works were first appearing. [pullquote][Claims] that doubts about the authorship did not begin until hundreds of years after Shakespeare’s time [are] not correct… it is clear that the Shakespeare authorship mystery began during Shakespeare’s lifetime…[/pullquote]

Anti-Stratfordians should make much more of those questioning allusions in any debate for they clearly belie the eternal orthodox protest that “no one doubted Shakespeare’s authorship during his lifetime.” Indeed, I can think of no other Elizabethan writer for whom there is such consistent recorded doubt and identity confusion in the contemporary record. It is especially worth noting that these guesses about “Shakespeare’s” identity occurred within the same time period during which Shakspere, we are told, was at the height of his fame and public exposure, hanging out in taverns with other leading writers, hobnobbing with the nobility, and acting onstage in front of thousands of people.

Which brings us back to 1591 and Farewell to Folly: Here, through Greene’s second allusion to Batillus, we can build an interesting chain of association:

Special note should again be taken of the last sentence of Greene’s paragraph, for there is a jarring shift in subject. First Greene is talking about how readers of his pamphlet might react to it. Then suddenly—though somehow included in his same train of thought as plagiarists and frontmen—he is thinking of someone who can’t write without the help of literate clerks. What? How could his readers, who “overread every line” of his pamphlet, not be able to write “true English”? Greene is clearly referring to a near-illiterate who is wanting to “make himself the father of interludes”5—that is, of theatrical pieces. Where does that come from?

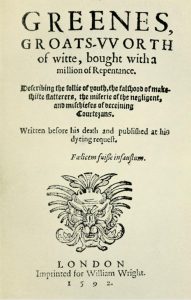

1592—Greene’s Groatsworth of Wit

Only a year after the publication of Farewell to Folly, in the first section of his Greene’s Groatsworth of Wit, appeared an apparently autobiographical account of how Greene was cheated and misused by a little-educated, pompous, well-off “country author” and “player” who paid down-and-out writers to create plays for him (Price 46).6

Only a year after the publication of Farewell to Folly, in the first section of his Greene’s Groatsworth of Wit, appeared an apparently autobiographical account of how Greene was cheated and misused by a little-educated, pompous, well-off “country author” and “player” who paid down-and-out writers to create plays for him (Price 46).6

This account—rarely mentioned by orthodox scholars—is followed by Greene’s frequently-quoted open letter to three playwrights, in which he urges them to cease providing plays to actors who will misuse them, as he himself was misused. In it Greene singles out one particularly offending actor—the “upstart crow” and “Shake-scene”—and implies that moneylending was one of the actor’s offenses (“an usurer”).

In that same year appears the first recorded activity of “Willelmus Shackspere” in London—as a moneylender, making a very large loan of seven pounds.7

Yes trust them not: for there is an upstart Crow, beautified with our feathers, that with his Tigers heart wrapped in a Players hide, supposes he is as well able to bombast out a blank verse as the best of you: and being an absolute Johannes fac totum, is in his own conceit the only Shake-scene in a country. (qtd. in Sobran 33)

Greene’s Mirror of Modesty dedication now becomes important, for the image of Aesop’s crow is presented there—equated with Batillus—and provides a reasonable basis for interpreting this passage; here Greene is again using the image of the crow in the same way, implying this “Shake-scene” actor was one of the “Batillus” front men about whom he had complained only a year earlier.8

In support of this interpretation, I have elsewhere argued that in this passage the word “supposes” is meant to be taken in the now obsolete sense of “pretends” (Dixon, Shakespeare Oxford Newsletter, Spring 2000, p. 7). To review, according to the Oxford English Dictionary, in the sixteenth century some definitions of the word “suppose” included:

12. To feign, pretend; occas. to forge. Obs.

13. To substitute by artifice or fraud […] Obs.

Related entries makes it clear that “suppose” had a definite secondary connotation of fraud and deception that it has since lost. For example, in The Taming of the Shrew Shakespeare, using the noun form of the word, wrote:

… Here’s Lucentio,

Right son to the right Vincentio,

That have by marriage made thy daughter mine

While counterfeit supposes bleared thine eyne. (5.1.118-121)11

In this example Shakespeare uses “suppose” as a noun which is translatable as “pretenses” or “substitutions.”

Another example: the OED lists the following definition for the related word “supposed”:

2. ‘Put on,’ feigned, pretended, counterfeit. Obs.

The following example is given: “He cuts the ring from the purse, and by his supposed man (rounding him in the eare) sends it to the plot-layer of this knauerie.”

This sentence is from a work listed as Conny Catch—dated 1592, written by Robert Greene.

Thus, if (1) Greene is known to have connected the image of Aesop’s crow with the image of a writer who deceptively took credit for another’s work (Batillus), (2) Greene is known to have complained in print—only a year before Groatsworth was published—about the practice in his day of anonymous authors employing front men who were credited with their work, and to have called such front men “Batilluses,” and (3) Greene is known to have used—in the very same year Groatsworth was published—the word “supposed” to mean “pretended,” it is reasonable to assume that when he again referred to the image of a crow wearing others’ feathers—one “supposing he could bombast out a blank verse”—Greene meant the upstart actor was pretending he could bombast out a blank verse.

If Greene had meant that the “Shake-scene” was just a full-of-himself actor/ writer who believed himself to be a great playwright, as traditional scholars insist, why would he have chosen the image of Aesop’s crow at all? This is an important point, for Aesop’s crow was not just a self-satisfied bird who “believed” himself to be genuinely beautiful. He was a fraud and con artist. Aesop’s crow was actively trying to deceive, to appear to be what he knew he was not. If “supposes” means “pretends,” Greene’s metaphor remains parallel, for Aesop’s crow pretended to be a beautiful bird. For the crow allusion to work we must also assume the “Shake-scene” was pretending to be an author. Consistent with Greene’s earlier usage of the crow image, pretending to be authors is exactly what “Batilluses” do.9

Another word in this famous passage has a secondary meaning which may be relevant to this point. Commentators always read the word “conceit” here as referring to a quality of “conceited-ness.”

However, the OED lists additional meanings for “conceit,” other than the usually understood “high self-estimation”:

III. Fancy; fanciful opinion, action, or production.

7. A fanciful notion; a fancy, a whim. [example—1611 DEKKER Roaring Girl: “Some have a conceit their drink tastes better in an outlandish cup than in our own.”]

7b. Fancy, imagination, as an attribute or faculty [example—1590 GREENE Orl. Fur.: “In conceit build castles in the sky.”]

8b. A fanciful action, practice, etc.; a trick. [example—1579 LYLY Euphues: “Practice some pleasant conceit upon thy poor patient.”]

“Conceit” thus also has meanings which imply something fantastically imaginary, unreal, untrue, and perhaps even purposely deceptive; and Greene is listed as having used the word in this sense only two years before Groatsworth. Commentators may have been misreading this passage for years. An equally plausible reading, but one radically different from the traditional, might be:

Yes trust them not: for there is an upstart con artist fraud, acting the part of a playwright, who with his Tigers heart wrapped in a Players hide, pretends he is as well able to bombast out a blank verse as the best of you: and being an absolute Johannes fac totum, is in his own imaginative production the only Shake-scene in a country.

This sounds very much like the near-illiterate who “needs make himself the father of interludes,” mentioned the year before, and the little-educated, play-commissioning actor from the previous section of Groatsworth. (Notice the reiteration of the word “country” here, pointing to an identification of this upstart “Shake-scene” with that pompous “country author” player.)

1593—Gabriel Harvey’s Pierce’s Supererogation

This new interpretation of Groatsworth is supported by the appearance seven months later of the pamphlet Pierce’s Supererogation, by Gabriel Harvey. As Mark Anderson has discovered, near the end of that pamphlet Harvey writes, in a section on the keeping of secrets:

Pap-hatchet talketh of publishing a hundred merry tales of certain poor Martinists; but I could here dismask such a rich mummer and record such a hundred wise tales of memorable note with such a smart moral as would undoubtedly make this pamphlet the vendablest book in London and the register one of the famousest authors in England. But I am none of those that utter all their learning at once… (qtd. in “Supererogation,” Shakespeare Matters, Spring 2003, p. 31)

A “mummer” is defined by the OED as “an actor in a dumb show.” Anderson translates this paragraph as:

Just as John Lyly (who took the nickname “Pap-Hatchet” in the Martin Marprelate quarrel) threatened to unmask Martin Marprelate, I could here unmask a rich actor—and in doing so, I could make this book the best-selling book in all of London and make yours truly the most famous author in all of England. But I won’t do that … (“Supererogation” 31)

Greene’s Groatsworth was registered on September 20, 1592. Harvey’s pamphlet Pierce’s Supererogation was registered on April 27, 1593. Thus, within a space of only seven months two works were registered in which references were made to an actor who had an identity secret—who was in a “mask,” who was “beautified” with others’ feathers, who was “supposing” to be a playwright. The time span between the two works can be shortened even further if we consider that some time must have passed between the registration of Groatsworth and its availability on the bookstands, and between Harvey’s writing of this passage and its own registration.

[pullquote]…within…seven months two works were registered in which reference were made to an actor who had an identity secret—who was in a ‘mask,’…‘beautified’ with others’ feathers…‘supposing’ to be a playwright.[/pullquote]

I disagree slightly with Anderson’s interpretation, for it implies that it was solely the dismasking of the mummer which would have made Harvey famous. Harvey’s phrasing implies that the actor’s secret was just one of many secrets he could have revealed. Still, why would a secret about a well-heeled actor be such a spicy topic that Harvey would single it out, among all his other “wise tales”?

Groatsworth is known to have caused a commotion upon publication, for when Thomas Nashe was accused of writing it he vehemently denied the charge, and the printer Henry Chettle reported there were protests specifically about the “upstart crow” letter and felt compelled to apologize. Harvey would almost certainly have been aware of this debacle, for he was involved in a pamphlet war with Nashe and his circle—which included Greene—at the time, and would very likely have found it difficult to resist getting a jab in.

Was Harvey bragging that, if he had wanted to, he could have revealed the truth of the situation alluded to in Greene’s controversial letter to playwrights? Was he saying that he could have “dismasked” the upstart actor who was pretending to be a playwright? If not, it then falls to orthodox scholars to provide an alternate explanation of who this “rich mummer” was, why he was in a “mask,” why his secret was so sensational, and why he should have been on Harvey’s mind at the time Harvey was writing this pamphlet.

With such a tempting reward before him, why did Harvey refrain from spilling the beans? Might it have been because some persons “of calling and gravity” (to recall Greene’s phrase) would have been displeased? That is a reasonable guess, for as Anderson points out, displeased persons of calling and gravity are precisely those who ended Harvey’s writing career: in 1599 the Archbishop of Canterbury and other authorities ordered all his works burned, and Harvey was ordered to stop writing (“Supererogation” p. 31). And Chettle did allude to “diverse of worship” having interceded in the “upstart crow” affair. (If Greene’s letter had been simply a matter of jealousy among playwrights—among the “Elizabethan equivalent of comic book writers”—as Stratfordians insist, one must wonder why people of “worship” would have even cared.)

In fact, Harvey himself hinted that this was the case. Immediately following on the above passage he continued:

…and the close man (that was no man’s friend, but from the teeth outward; no man’s foe, but from the heart inward), may percase have some secret friends, or respective acquaintance, that in regard of his calling, or some private consideration, would be loath to have his coat blazed, or his satchel ransacked.

Apparently this “rich mummer” had friends in high places. It is interesting that Harvey follows his coy threat to dismask the actor with a reference to this “close” [i.e. secretive] man having an acquaintance of “calling” who is apparently “loathe” to have the actor’s secret publicly exposed. This language, of course, recalls Greene’s original “Batillus” commentary two years earlier about “poets, which for their calling and gravity, being loath to have any profane pamphlets pass under their hand …” And given the “calling” of this secret friend, one wonders if the coat he was loath to have “blazed” was a coat-of-arms, and what exactly he might have had in his satchel that he was afraid people would discover. [pullquote]Harvey follows his coy threat to dismask the actor with a reference to this ‘close’ [i.e. secretive] man having an acquaintance of ‘calling’ who is apparently ‘loathe’ to have the actor’s secret publicly exposed.[/pullquote]

The reference to the mummer’s hypocrisy—that is, being charming toward people (a friend “from the teeth outward”), while nursing secret malevolent thoughts toward them (a foe “from the heart inward”)—also sounds very like the Shake-scene actor of six months earlier, described as having a “tiger’s heart wrapped in a player’s hide.”

Given the relatively compact time frame here—1591 through early 1593—it is reasonable to hypothesize that in the early years of the 1590s rumors were floating around the London literary world of at least one person—an actor—who was taking credit for others’ writings; that there was curiosity about the situation; and that some people in the know were offended by it.

It is also worth noting that Harvey’s description of the mummer as “rich”—something very few actors of the time could claim to be—again recalls the well-off, moneylending, play-commissioning player Greene had described seven months earlier.10 That is not the end of the story, however. An epilogue:

1603—Henry Crosse’s Vertues Commonwealth

As Diana Price has shown, in 1603 Henry Crosse referred back to Groatsworth, echoing Greene’s complaints about actors in general, picking up on his connection between actors and moneylenders, re-using some of Greene’s wording (“anticks,” “puppets”), and reiterating the “Grasshopper and the Ants” fable told in the final, rarely-mentioned section of Groatsworth (54-56). Crosse wrote:

He that can but bombast out a blank verse, and make both the ends jump together in a rhyme, is forthwith a poet laureate, challenging the garland of bays, and in one slavering discourse or other, hang out the badge of his folly. Oh how weak and shallow much of their poetry is … in so much that oftentimes they stick so fast in mud, they lose their wits ere they can get out, either like Chirrillus, writing verse not worth the reading, or Batillus, arrogating to themselves, the well deserving labors of other ingenious spirits. (qtd. in Price 55)

Some Oxfordians argue that Greene’s earlier passage about the upstart actor “bombasting out a blank verse” refers to the actor’s improvising on stage—that is, verbally adding words to the playwright’s written text—and not to the actual writing of plays. Crosse, however, makes it clear that the bombasters he is thinking of were dealing in written words (“writing verse not worth the reading”)—whether they actually wrote them or not.

Here it is also notable that Crosse refers back to the subject of Batillus at all, as Greene himself didn’t mention “Batillus” in the “Shake-scene” passage Crosse is referring back to. The fact that Crosse should have done so is an indication that in the Elizabethan mind the association of “Aesop’s crow = Batillus” was a readily understood convention.

It should also be noted that Crosse’s passage is the only contemporary interpretation of the Groatsworth letter we have. Stratfordians may continue to argue that the “Shake-scene” passage simply reflects Greene’s envy that a mere actor should show success at writing, but the existing documentary evidence does not support that interpretation. Instead, it suggests that Elizabethans interpreted the passage as referring—at least in part—to an unethical “Batillus”-type figure, one associated with actors, taking credit for others’ work.

In response, Stratfordians protest that the moralist Crosse was complaining about bad and unethical poets in general, not about the “Shake-scene” actor specifically. (In their minds, of course, he is Shakspere/ Shakespeare.) Still, it cannot be denied that a passage about heartless actors misusing playwrights for some reason put Crosse in mind of unethical poets taking credit for others’ work. On the surface those are two quite different subjects. One wonders why they were so associated in Crosse’s mind that the Groatsworth letter should have inspired that mental leap. Further, it cannot be denied that the specific passage which turned Crosse’s mind to thoughts of Batillus “arrogating to [himself] the well deserving labors of other ingenious spirits” was a passage in which one—and only one—offending actor was singled out: the “Shake-scene.” Even ten years later people were still suspecting something fishy with “Shakespeare” and the actors.

All this presents a picture that is internally consistent from a number of different angles. In the case of Groatsworth specifically, it is the most reasonable interpretation—and it completely undercuts Stratfordians’ only contemporary document tying (they believe) Shakspere of Stratford to a literary career. In fact, it actually turns their strongest weapon against them. To review:

1591: Robert Greene stated that in his time there was a practice of certain highly-placed anonymous writers of “calling,” in order to protect their reputations, employing front men to take credit for their work. Greene associated such front men with the historical Batillus. (He had earlier associated Batillus with Aesop’s crow.) Greene then tied those contemporary front men to a near-illiterate who wished to be thought “the father” of theatrical pieces.

1592: Greene wrote of how he was misused by a little-educated, well-off “country” actor who hired others to write plays for him. Then, in a letter warning playwrights against unethical actors in general, Greene expressed anger at one specific actor, referring to him (again in reference to “the country”) as a “Shake-scene,” emphasizing his callousness and hypocrisy, associating him with Aesop’s crow, and saying he “supposed” himself a playwright. He connected this actor to moneylending activities. In this same year Greene had elsewhere used the word “supposed” to mean “pretended.”

1592: “Willelmus Shackspere” is recorded as having loaned a large amount of money in London.

1592: Greene’s “Shake-scene” letter created a controversy and Chettle acknowledged that highly-placed people had interceded and put pressure on him about publishing it.

1593: About six months later, Harvey—in a pamphlet that was part of his ongoing war with the literary circle with which Greene was associated—bragged that he knew a sensational secret about a well-off, malicious, hypocritical actor whom he could have “dismasked” if he had wanted to. This actor had a highly-placed “secret acquaintance” of “calling” who was “loath” to have the actor’s secret, and his own identity, revealed.

1603: Ten years later Crosse referred back to Groatsworth, interpreting the “Shake-scene” letter as referring in part to moneylending actors and people who were involved in such unethical “Batillus”-type activities as taking credit for others’ writing.

Stratfordians have always insisted that the blank-verse-bombasting “Shake-scene” actor of Groatsworth is their beloved moneylending Stratfordian entrepreneur, William Shakspere. AntiStratfordians can now afford to cheerfully agree with them on this, for given the picture presented above, the case for the “Shake-scene” being merely a front man for the true, hidden author of the Shakespeare plays—Greene does, after all, allude to 3 Henry VI in his passage—is quite substantial indeed.

References:

- Here is the relevant Aesop fable of the crow (a “jackdaw” is the smallest member of the crow family) who “decked” and “beautified” himself with others’ feathers:

The Vain Jackdaw

Jupiter determined, it is said, to create a sovereign over the birds, and made proclamation that on a certain day they should all present themselves before him, when he would himself choose the most beautiful among them to be king. The Jackdaw, knowing his own ugliness, searched through the woods and fields, and collected the feathers which had fallen from the wings of his companions, and stuck them in all parts of his body, hoping thereby to make himself the most beautiful of all. When the appointed day arrived, and the birds had assembled before Jupiter, the Jackdaw also made his appearance in his many feathered finery. But when Jupiter proposed to make him king because of the beauty of his plumage, the birds indignantly protested, and each plucked from him his own feathers, leaving the Jackdaw nothing but a Jackdaw. (Aesop)

- It is impossible to reference all the messages regarding “Batillus” posted on the ‘hlas’ discussion group, of course, but anyone who goes to Google can search the term for themselves under “Groups.” Restrict the search to the group “humanities.lit.authors.Shakespeare” and enter the search term “Batillus.”

- Greene’s sentence—“And he that can not write true English without the help of clerks of parish churches will needs make himself the father of interludes.”—of course puts one in mind of the infamously crude surviving signatures of William Shakspere, about which experts on historical documents and handwriting have made comment. (See Price, Ogburn, Whalen for more detailed commentary.)

- It is worth mentioning that in 1589, immediately before this decade of ambiguity and confusion about the Shakespeare authorship, the author of the Arte of English Poesie, in addition to revealing that some noblemen were publishing poetic works under names other than their own, also singled out Edward de Vere as being “first” among a number of noblemen who would have been acknowledged to write “excellently well” if their “doings could be found out and made public with the rest.” (Sobran 134)

- The OED defines an “interlude” as

A dramatic or mimic representation, usually of a light or humourous character, such as was commonly introduced between the acts of the long mystery-plays or moralities, or exhibited as part of an elaborate entertainment.

Interludes were popular in the early to mid-1500’s, and by the time of Greene’s quote in 1591 would have been old hat; yet he speaks of the near-illiterate in the present tense. We may guess he was deliberately choosing an old-fashioned “crude” style of drama to point up the unsophisticated nature of the one who “can not write true English,” yet would “make himself the father” of theatrical pieces. - I have written as if it is a fact that Robert Greene was the author of Greene’s Groatsworth. As is well known in anti-Stratfordian circles, there is room to doubt this. I wrote as I did for the sake of clarity and convenience, for it doesn’t hurt the case if Groatsworth was actually written by Chettle or some other person claiming to be Greene.

If such was the case, it would merely indicate that someone was attempting to write in Greene’s style, using his previous imagery and language. That person can still easily be posited to have been someone involved in the London literary and theatrical scene who was “in the know” about the upstart “Batillus” actor, and Greene’s history with that actor. In fact, it can be posited even further that the anonymous writer purposely chose to complain about this apparently touchy subject (if we are to take Harvey’s reticence to reveal it as an indication of such) under the name of “Robert Greene” because he knew that: 1) Greene had already protested against the practice of employing front men only a year before; and 2) Greene was now safely dead and beyond retribution.

Most Stratfordians, however, continue to insist that Greene was the true author of Groatsworth. Oxfordians can now easily afford to agree with them in this, for, given the above, that position hurts them even more than if Greene had not been the true author. Given Greene’s documented attitude toward the “Batillus” front men of his time, his documented equation of a crow wearing others’ feathers with Batillus, and his documented use of “supposed” to mean “pretended” in the very same year Groatsworth was published, it is consistent with his prior writings that he should have used the image of Aesop’s crow to complain of an actor/front man pretending to be a playwright. - As Diana Price points out, orthodox scholars typically reject this 1592 “Clayton loan” as referring to “some other Shakespeare,” even though it is congruent with Shakspere’s known later moneylending activities. The only reason this fact is rejected is that it does not square with Stratfordians’ belief about Shakespere’s early London career. It is awkward for them to picture their gentle, sensitive, aspiring poet making his City debut as a moneyed “usurer” (20-23) (This even despite the fact that in that very same year Robert Greene clearly implied that the “Shake-scene”—whom Stratfordians believe was Shakspere—was involved in moneylending: That section of Greene’s paragraph is typically edited out and ignored in orthodox biographies.

- Although in this passage the crow isn’t specified as Aesop’s crow, as in Greene’s first allusion, and although the Classical image of a crow was also used generally in Elizabethan times to refer to a plagiarist, or an undeserving bird on a privileged perch (Price 48), we may guess that here Greene was referring again to Aesop’s crow, for it was only Aesop’s crow who specifically “beautified” himself with others’ feathers.

- Another fable by Aesop sheds light on the character of the crow as a “pretender,” rather than a “believer”:

The Jackdaw And The Doves

A jackdaw, seeing some Doves in a cote abundantly provided with food, painted himself white and joined them in order to share their plentiful maintenance. The Doves, as long as he was silent, supposed him to be one of themselves and admitted him to their cote. But when one day he forgot himself and began to chatter, they discovered his true character and drove him forth, pecking him with their beaks. Failing to obtain food among the Doves, he returned to the Jackdaws. They too, not recognizing him on account of his color, expelled him from living with them. So desiring two ends, he obtained neither. (Aesop)

- It is worth noting that Harvey makes this seemingly out-of-the-blue allusion to the “rich mummer” at the end of a pamphlet in which, as Anderson points out, he also ridicules an incident from the life of Edward de Vere, and seems to allude to, and parody, Shakespeare’s soon-to-be published Venus and Adonis (“Potent Testimony”, “Ross’s Supererogation”). It can thus be argued that Edward de Vere, the well-off actor Shakspere, and the author “Shakespeare” were all apparently associated in Harvey’s mind. If Harvey was indeed aware of de Vere’s authorship secret and his use of Shakspere as a front, his reference to a secret about a “rich mummer” suddenly makes a lot of sense: In such a context it would have been a very pointed “tale” for him to single out—a way of indirectly saying, “Hey, Oxford and your cronies: I know your secret and could ruin it for you if I wanted to.” In fairness, however, it must also be noted that several years later, sometime circa 1598-1601, Harvey seemed to be of the opinion that Sir Edward Dyer was the author of Venus and Adonis, writing, “The younger sort takes much delight in Shakespeare’s Venus, & Adonis: but his Lucrece, & his tragedy of Hamlet, Prince of Denmark, have it in them, to please the wiser sort. Or such poets: or better: or none. [following appear the Ovidian lines from the title page of Venus and Adonis]

Vilia miretur vulgus: mihi flavus Apollo Pocula Castalieae plena ministret aquae:

quoth Sir Edward Dyer, between jest, & earnest. Whose written devises far excel most of the sonnets, and cantos in print.” (qtd. in Price 225, citing G.C.M. Smith, Gabriel Harvey’s Marginalia, 232-233) This, of course, suggests that Harvey believed that Dyer, not Oxford, was Shakespeare, and thus conflicts with the above Oxfordian interpretation of Pierce’s Supererogation. Or, perhaps, it implies that Harvey knew both Oxford and Dyer to have had hands in writing “Shakespeare.” Whatever the case, this quote definitely indicates that Harvey believed there was some kind of authorship deception going on around the writer “Shakespeare,” and demolishes once and for all the bedrock Stratfordian claim that “no one doubted Shakespeare’s authorship during his lifetime.”

Works cited:

Aesop. Fables. translated by George Fyler Townsend. Online: http://www.literature. org/authors/aesop/fables/

Anderson, Mark. “The Potent Testimony of Gabriel Harvey.” Shakespeare Matters. 1.2 (2002): 26-29.

—“Ross’s Supererogation.” Shakespeare Matters. 1.3 (2002): 28-31.

Dixon, Jonathan. “The Upstart Crow Supposes.” The Shakespeare Oxford Newsletter. 36.1 (2000): 7.

Greene, Robert. The Life and Complete Works in Prose and Verse of Robert Greene, M. A. Ed.

Alexander B. Grosart. 15 vols. London: The Huth Library, 1881-86. [Thanks to Diana Price for providing photocopies].

Michell, John. Who Wrote Shakespeare? New York: Thames and Hudson, 1996.

Ogburn, Charlton. The Mysterious William Shakespeare: The Myth and the Reality. 1984. (2nd ed. McLean, VA: EPM Publications, 1992).

Price, Diana. Shakespeare’s Unorthodox Biography: New Evidence of an Authorship Problem. Westport, CT: Greenwood Press, 2001.

Sobran, Joseph. Alias Shakespeare: Solving the Greatest Literary Mystery of All Time. New York: The Free Press, 1997.

Whalen, Richard F. Shakespeare: Who Was He? The Oxford Challenge to the Bard of Avon. Westport, CT: Praeger, 1994.

Jonathan Dixon is an actor, illustrator, composer and counselor based in Santa Fe, New Mexico. He was a member of the acclaimed Theaterwork company and has had principal roles in the series’ Longmire, Preacher, Gunslingers, and Killer Women, as well as the film War On Everyone. He is also an artist who has illustrated several works by Lewis Carroll, and a songwriter/composer. He recently wrote the musical score for the award-winning animated featurette The House of the Seven Gables (for which he also recorded the voice of Mr. Holgrave), and in 2017 his setting of “The Carol of the Field-Mice” (from The Wind in the Willows) was requested to be performed at the Royal Academy of Dramatic Art’s Christmas concert in London. Facebook and IMDb: Jonathan David Dixon.

Membership dues cover only a fraction of our budget, including all our research, preservation and programming. Please support the SOF by making a gift today!

Blue Boar Tavern: Wassail Q&A

Tuesday Dec. 17, 8pm E / 5pm P

Sign up below for event invites!