by Ramon Jiménez

The anonymous history play, The True Tragedy of Richard the Third, printed in 1594, has occasionally been cited as a source for Shakespeare’s Richard III, printed in 1597, also anonymously. True Tragedy was not printed again until 1821, and was not commented on at length until 1900, when G. B. Churchill found sufficient parallels between the two plays to assert that Shakespeare took incidents and language from the anonymous playwright (524). Fifty years later, John Dover Wilson agreed, and pointed out additional links between the plays (Shakespeare’s 299-306). In 1960, Geoffrey Bullough (3.222, 238) concurred with Churchill and Wilson, and printed most of True Tragedy at the end of his discussion of Richard III in his Narrative and Dramatic Sources of Shakespeare (iii 317-45). On the other hand, most commentators, including E. K. Chambers (Elizabethan iv, 44) and the editors of the recent Arden and Oxford editions of Richard III, see only scattered minor borrowings by Shakespeare from the old play. Several early critics ascribed the play variously to Lodge, Peele, Kyd, and the author of Locrine (Chambers Elizabethan iv, 44). Aside from occasional comments about its insignificance, True Tragedy has been largely ignored by scholars for the past forty years. With the exception of a hint from the maverick scholar Eric Sams in 1995 (59), no one has ever claimed the play for Shakespeare, nor has it been included in discussions or collections of Shakespearean apocrypha.

The anonymous history play, The True Tragedy of Richard the Third, printed in 1594, has occasionally been cited as a source for Shakespeare’s Richard III, printed in 1597, also anonymously. True Tragedy was not printed again until 1821, and was not commented on at length until 1900, when G. B. Churchill found sufficient parallels between the two plays to assert that Shakespeare took incidents and language from the anonymous playwright (524). Fifty years later, John Dover Wilson agreed, and pointed out additional links between the plays (Shakespeare’s 299-306). In 1960, Geoffrey Bullough (3.222, 238) concurred with Churchill and Wilson, and printed most of True Tragedy at the end of his discussion of Richard III in his Narrative and Dramatic Sources of Shakespeare (iii 317-45). On the other hand, most commentators, including E. K. Chambers (Elizabethan iv, 44) and the editors of the recent Arden and Oxford editions of Richard III, see only scattered minor borrowings by Shakespeare from the old play. Several early critics ascribed the play variously to Lodge, Peele, Kyd, and the author of Locrine (Chambers Elizabethan iv, 44). Aside from occasional comments about its insignificance, True Tragedy has been largely ignored by scholars for the past forty years. With the exception of a hint from the maverick scholar Eric Sams in 1995 (59), no one has ever claimed the play for Shakespeare, nor has it been included in discussions or collections of Shakespearean apocrypha.

However, a review of the published evidence, and a further analysis of the two plays, strengthen the conclusion that it was a source play for Shakespeare’s Richard III. Furthermore, this investigation reveals the high probability that it was Shakespeare himself who wrote the anonymous play, and that his Richard III was his major revision of one of his earliest attempts at playwriting. There are also significant links between this anonymous play and Edward de Vere, 17th Earl of Oxford, that add to the evidence that he was the actual author of the Shakespeare canon. Lastly, the evidence suggests that this play was performed for an aristocratic audience, possibly including Queen Elizabeth herself, in the early 1560s, when de Vere was between thirteen and fifteen years old.

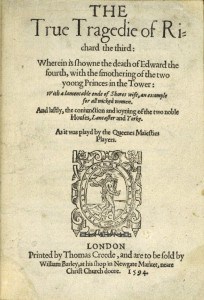

The title page of the quarto printed in 1594 by Thomas Creede reads “The True Tragedie of Richard the Third: Wherein is showne the death of Edward the fourth, with the smothering of the two yoong Princes in the Tower : With a lamentable ende of Shore’s wife, an example for all wicked women. And lastly the conjunction and joyning of the two noble Houses, Lancaster and Yorke. As it was playd by the Queenes Majesties Players” (Greg, Tragedy xiii). An entry credited to Thomas Creede in the Stationers Register on June 19 of the same year contained roughly the same language, except that it began “An enterlude entituled, The Tragedie of Richard the Third.” Thus, the three extant copies of True Tragedy could be the earliest printed Shakespeare plays that survive, with the exception of the single extant copy of Titus Andronicus, printed early in the same year.

True Tragedy was not reprinted until the nineteenth century, when it was included in three collections of old plays. In the Malone Society reprint of 1929, the only subsequent edition, the editor, W. W. Greg, wrote: “Nothing whatever is known of the history of the piece beyond the statement on the title-page that it ‘was playd by the Queenes Majesties Players’” (Tragedy v). There is no record of its performance, nor is it mentioned in any document from the period. In this article, line references to the play refer to the Malone edition.1

The quarto text reproduced in the Malone edition gives every appearance of being set from a manuscript prepared by someone listening to the play being performed or dictated, the latter being more likely. Although the spelling is erratic throughout, there are numerous misspellings based on apparent mishearings. There are also long stretches of misaligned text, that is, verse printed as prose and vice versa. A large portion of another Queen’s Men play registered by Creede in 1594, The Famous Victories of Henry the Fifth, was printed as verse (in 1598), even though the entire play was written in prose. The misaligned text in these quartos is not easily explained, and may have been due to errors or deliberate changes by one or more transcribers and one or more compositors.2

E. A. J. Honigmann (304-5) and others date True Tragedy later than Shakespeare’s Richard III, but most editors agree that although Richard III may have been written as early as 1592, True Tragedy was the earlier composition. Besides the ample evidence for an early date, the versification, plotting, and wealth of imagery and characterization in Shakespeare’s play are so superior that it is impossible to imagine a dramatist, after reading Richard III, producing a manuscript on the same subject and with the same title, without including a great deal more of Shakespeare’s language and imagery. For further evidence of an early date, see “The Date, etc.” below.

The original source for both plays was Sir Thomas More’s The History of King Richard the Third, a short biography first published in 1543 by Richard Grafton as a continuation of John Hardying’s rhymed Chronicle of Jhon Hardying (sic). The apparent immediate source for both plays was Edward Hall’s The union of the two noble and illustre famelies of Lancastre and Yorke, published by Grafton in 1548.3 Scholars have found details in Shakespeare’s play that may have been taken from Raphael Holinshed’s The Chronicles of England, Scotland, and Ireland, published in 1577 and again in 1587. For the period covered by both plays, the Hall and Holinshed chronicles are nearly identical with More. Wilson identified incidents and language in Richard III that derived from A Mirror for Magistrates, a collection of linked verse biographies of tragic figures in English history by various authors that was first published in 1555 (Richard xxiv-xxviii). Similarly, language and details about Shore’s Wife in True Tragedy were based on the poem about her by Thomas Churchyard that was added to A Mirror in 1563, in the third edition (Churchill 409-13; also, see “The Thomas Churchyard Connection” below).

General Similarities between True Tragedy and Shakespeare’s Richard III

As J. D. Wilson wrote, “Richard III and T. T., for all their differences, are strikingly similar in general structure” (Shakespeare’s 300). The first act of Richard III corresponds roughly to the Induction scene in True Tragedy, in which the ghost of George, Duke of Clarence, appears briefly to the characters Truth and Poetry, and calls, in Latin, for a quick and bloody revenge. Truth then recounts to Poetry the events of the 1460s—the seizing of the throne from Henry VI by Richard Plantagenet, Richard’s death at Wakefield, the accession of his brother Edward IV, and the murder (in 1471) of Henry VI by Richard, Duke of Gloucester. When Poetry asks the identity of the ghost, Truth replies that it is Clarence, and that he was also a victim of Richard, by drowning in a butt of wine, a death that occurred in 1478. Truth then describes Richard as:

A man ill shaped, crooked backed, lame armed, withal,

Valiantly minded, but tyrannous in authority (57-8)

Finally, Truth suggests to the audience that they imagine that Edward IV, after reigning twenty-two years, has summoned his nobles to the court to hear his death-bed wishes, an event recorded in the chronicles as taking place in April, 1483. Here the action of the play begins, with the departure of Truth and Poetry and the entrance of King Edward, Lord Hastings, Queen Elizabeth, and her son Thomas Grey, Marquess of Dorset. The concluding sentence of the stage directions reads “To them, Richard.”

In the first act of Richard III there is a similar compression of historical events, from the funeral of Henry VI in 1471 to the murder of Clarence in 1478. In his opening soliloquy, Richard describes himself in language similar to that used in True Tragedy—“not shap’d for sportive tricks,” etc. Act 2 opens at the same time and in the same place that True Tragedy begins—in 1483, with King Edward on his death-bed attempting to reconcile his nobles. The cast of characters is nearly the same, and Richard enters, with Ratcliffe, after forty-four lines. The remainder of both plays is based on events in the sixteen-month period ending with the Battle of Bosworth and the crowning of Henry VII in August, 1485.

Shakespeare’s Richard III departs from True Tragedy in only two significant ways. One is in the depiction of women and Richard’s interaction with them. Queen Elizabeth, the widow of King Edward, and her daughter, also called Elizabeth, are present in both plays. True Tragedy includes two other women, Jane Shore and her maid Hursly—Jane being the unfortunate former mistress of Edward IV. Nowhere in True Tragedy does Richard speak to any of them.

Shakespeare’s play deletes Shore and Hursly, but adds three other women. One is the widowed Duchess of York, mother of the infamous Plantagenet brothers, Richard, Edward, and George. Another is the widow of Henry VI, Margaret of Anjou, who died in 1482, but was such a brilliant character in the three Henry VI plays that Shakespeare brought her back for a fourth appearance in Richard III. The third was another widow, Lady Anne Neville, who was successfully courted by Richard, and became his queen briefly before she mysteriously died. And Richard speaks to all of them, at length, with great irony and wit.

Shakespeare has also spiced up the action by adding two courtships, both by Richard—one of Anne Neville, and the other directed to Edward’s widow Elizabeth for the hand of her daughter, also Elizabeth.

These additions illustrate Shakespeare’s maturity and increasing dramatic skill—and bring humor, irony, depth, and balance to the rather grim story told in True Tragedy. They also reflect the older writer’s experience with women, ranging from the evil to the innocent, something more likely to lie in the future of a teen-aged boy.

The other major difference between the two plays is the treatment of the murders of Edward IV’s two young sons, and of his brother George. In True Tragedy it is the murder of the two princes in the Tower that is dramatized; the murder of George, Duke of Clarence, is only reported. In Richard III it is the murder of Clarence that is dramatized, and the murder of the princes that is reported.

With respect to time and circumstance, the murder of the princes in True Tragedy adheres more closely to the sources. It occurred in 1483, after Richard was crowned King, and there is still disagreement about his guilt. The murder of Clarence in Richard III occurred five years before the action of the play, and it is likely that Richard was not responsible for it.

Similarities in Language, Incident, and Detail

The dozens of instances of similar language, incident, and detail in Richard III and True Tragedy fall into two categories—those that are clearly derived from one or more of the sources, and those that are unsupported by the sources, and are peculiar to the two plays. In their aggregate they are unmistakable, and supply convincing evidence of Shakespeare’s familiarity with True Tragedy, and frequent borrowing from it.

In the first category are the following:

1. The dismayed reactions of Jane Shore in True Tragedy (265-71) and of Queen Elizabeth in Richard III (1.3.11-16) to the prospect of Richard as Protector after the death of Edward IV. As Wilson remarked, “the contexts are so similar in T. T. and Richard III that it is difficult to deny a connection between them even though Jane Shore speaks in the one and the Queen in the other” (Shakespeare 302-3). All but one of the sources record that Richard was appointed Protector by the Council after the prince arrived in London to be crowned. No reference to this appointment is made in either True Tragedy or Richard III (Churchill 499-501).

2. Richard’s approach to his page for the name of a suitable murderer.

3. Richard as the murderer of Clarence, and Clarence’s ghost as the seeker of revenge.

4. The role of Sir Robert Brakenbury as supplier of the Tower keys to the murderers.4

5. The reconciliation scene at the time of Edward’s death.

6. Richard’s arrest and execution of the Queen’s brother Earl Rivers and her son Thomas, Lord Grey.

7. Richard’s claim that Queen Elizabeth and Jane Shore have bewitched him and caused his arm to be withered.

8. Richard’s arrest and beheading of William Hastings, the Lord Chamberlain.

9. The Duke of Buckingham’s public support for Richard as King, and the episode in which Richard first refuses the crown, then accepts it.

10. Buckingham’s rebellion and his subsequent capture and beheading.

11. Richard’s interaction with Thomas, Lord Stanley (with the differences described below).

12. The approach of the two armies toward the site of the Battle of Bosworth.

In the second category are the following examples of language, incident, and detail in both plays that are not found in the sources:

1. In True Tragedy the playwright uses an unusual dramatic device to show Richard cleverly claiming for himself the blessing Buckingham intends for King Edward:

Buckingham: Sound trumpet in this parley, God save the King.

Rich. Richard. (785-6)

In the long scene after the funeral of Henry VI in Act 1 of Richard III, Shakespeare employs the identical device to show Richard deflecting Queen Margaret’s curse on him back on herself:

Q. Margaret: . . . Thou loathed issue of thy father’s loins,

Thou rag of honour, thou detested

Richard: Margaret!(1.3.232-4)

2. In True Tragedy it is the murder of the two princes that is dramatized; in Richard III it is the murder of Clarence. However, the instructions to the hired murderers, by James Tyrell in True Tragedy, and by Richard in Shakespeare’s play, are similar, as are the responses, and have no basis in any chronicle:

Tyrell: Come hither, sirs. To make a long discourse were but a

folly. You seem to be resolute in this cause that Myles Forest

hath delivered to you. Therefore, you must cast away pity, and not

so much as think upon favour, for the more stern that you

are, the more shall you please the King.

Will.: Zounds, sir! Ne’er talk to us of favour. Tis not the first

that Jack and I have gone about.(True Tragedy 1223-29)

Richard: . . . When you have done, repair to Crosby Place.

But, sirs, be sudden in the execution,

Withal obdurate, do not hear him plead,

For Clarence is well-spoken, and perhaps

May move your hearts to pity if you mark him.

First Murderer: Tut, tut, my lord, we will not stand to prate.

Talkers are no good doers. Be assured,

We go to use our hands, and not our tongues. (Richard III 1.3.345-52)

3. The murderers’ discussion of how they will do the deed, the depiction of the actual murder, and their conversation about disposing of the bodies are similar in the two plays (1295-1316 in True Tragedy; 1.4.99-152, 258-73 in Richard III). In each case, one of the murderers is reluctant to proceed, but after the other remonstrates with him, he readily turns to the task. Another similarity is how the murders are reported. In True Tragedy, Tyrell asks, “How now Myles Forest, is this deed dispatcht?” Forest answers, “Aye sir, a bloody deed we have performed” (1319-20). In Richard III, the Second Murderer says “A bloody deed and desperately dispatch’d” (1.4.261). None of these details can be found in the sources (Boswell-Stone 348).

4. The King’s death-bed scene, and his attempt to reconcile his nobles, are described in the chronicles and occur in both plays, although the group of participants is not identical. But in both plays Richard is present, whereas none of the chronicle accounts place him there; and he was actually in Yorkshire at the time (Seward 260).

5. There is similar language and detail in the lamentation scenes in both plays. In True Tragedy, Queen Elizabeth mourns the loss of her husband Edward IV ( 789-811). In Richard III the Duchess of York, using similar language, mourns the loss of her husband and sons, and the widowed Queen Elizabeth that of her husband (2.2.1-100). In both plays, the children of the mourning women are called “images” of their fathers. In both plays, children ask the women whom they are mourning. In True Tragedy, Elizabeth is comforted by her three children, her daughter saying, “Good mother, expect the living, and forget the dead.” In Richard III, the Duchess is comforted by Clarence’s children, and Elizabeth by Earl Rivers, who says “Drown desperate sorrow in dead Edward’s grave, / And plant your joys in living Edward’s throne” (2.2.99-100). These scenes and this language have no counterpart in the chronicles (Lull 104).

6. As Churchill pointed out, young Prince Edward displays an unusual maturity for a thirteen-year-old in both plays (505-6). His remarks about what he will accomplish as King in True Tragedy (530-37) are similar to those in Richard III (3.1.76-94).

7. The repeated references to Thomas, Lord Grey, as the uncle of Prince Edward are identical errors in both plays. He was actually the Queen’s oldest son by her first husband, Sir John Grey, and therefore Edward’s half-brother. None of the sources contains this error.

8. The discussion of the size of the train to accompany Prince Edward to London for his coronation in True Tragedy (492-503) is echoed in Richard III (2.2.117ff). Although this discussion is mentioned by both More and Hall, the dialogue in both plays includes several identical words – train, malice, green, and break— that do not occur in the sources. These “verbal links” were strong enough to convince both J. D. Wilson (Shakespeare’s301) and W. W. Greg (Problem 80-1) that Shakespeare was influenced by the language in the same scene in True Tragedy. Churchill remarked that “The agreement between these two passages and especially the agreement between the two speeches of Rivers, is far closer than the agreement of either scene with the chronicle (505).”

9. In both plays the plan to separate Prince Edward from his kinsmen on their trip to London originates with Buckingham (True Tragedy 408-11; Richard III 2.2.146-50). However, in the only mention of this detail in the chronicles (More, copied by Hall), it is Hastings, Buckingham, and Richard who are responsible for the scheme.

10. The scene in which the Queen is informed of her relatives’ imprisonment is dramatized similarly in both plays. The stage direction, “Enter a messenger,” is identical. In True Tragedy, the dialogue proceeds:

York. What art thou that with thy ghastly looks presseth in-

to sanctuary, to affright our mother Queen?

Messen. Ah, sweet Princes, doth my countenance bewray me?

My news is doubtful and heavy.(813-16)

In Richard III:

Arch. Here comes a messenger. What news?

Mess. Such news, my Lord, as grieves me to report.

(2.4.38-9)

11. The responses to young Prince Edward’s reaction to the arrest of Lord Rivers and Lord Grey are similar in the two plays. In Richard III (3.1.1-16) Prince Edward expresses sadness and frustration that his uncles are not in London to welcome him. In True Tragedy (747-76), his complaint is more extensive and pointed. In both plays he protests that Lord Grey, in particular, is innocent of wrongdoing. In True Tragedy, Richard responds by suggesting that what has taken place is “too subtle for babes,” and that the Prince is a child and being used as such. In Shakespeare’s play, Richard responds similarly to the effect that the Prince is too young and inexperienced to understand the duplicity of dangerous men. In the only chronicle that mentions any response to the Prince’s remarks, Hall merely notes that Buckingham, not Richard, tells the Prince that his uncles have concealed their actions from him (Churchill 506). Thus, the response by Richard and the language he uses are peculiar to the two plays, and not supported in any source.

12. At the same place in the action in both plays, after the execution of Rivers, Grey, and Vaughan, and just prior to the condemnation of Hastings, Richard makes a similar observation about his rising late, and then adds a distinctive remark. In True Tragedy he says:

Go to no more ado, Catesby; they say I have been a long

sleeper to day, but I’ll be awake anon to some of their costs. (925-6)

In Richard III he says

My noble lords and cousins all, good morrow:

I have been long a sleeper: but I trust

My absence doth neglect no great design,

Which by my presence might have been concluded. (3.4.22-5)

More, Hall, and Holinshed all use the identical language to describe this scene: “These lords so sitting together communing of this matter, the protector came in among them, first about nine of the clock, saluting them courteously, and excusing himself that he had been from them so long, saying merely that he had been a sleeper [More writes “a slepe”] that day.” In both plays, the dramatist took two separated and unrelated words, “long” and “sleeper,” and combined them into a distinctive phrase. They both then added a remark by Richard that neither occurs nor is implied in any of the chronicles. In True Tragedy it is a veiled threat; in Shakespeare it is facetious, if not sarcastic.

13. In both plays an identical dramatic device is used to reveal that Richard is being called “King” even before Prince Edward’s planned coronation. In True Tragedy, Prince Edward (whom the playwright has identified as King since the death of his father) asks Myles Forest who was given the keys to the Tower:

Forest.My Lord, it was one that was appointed by the King

to be an aide to Sir Thomas Brakenbury.

King. Did the King? Why Myles Forest, am not I King?

Forest. I would have said, my Lord, your uncle the Protector. (1271-74)

In Richard III, Shakespeare uses the same slip of the tongue for the same purpose, except that the exchange is between Brakenbury, the Keeper of the Tower, and Queen Elizabeth. Brakenbury refuses to allow her to visit her two sons, saying:

I may not suffer you to visit them:

The King hath strictly charg’d the contrary.

Eliz. The King! Who’s that?

Brak. I mean the Lord Protector. (4.1.16-19)

14. In Scene 4 of True Tragedy, Richard muses upon the prospect of wearing the crown:

Why so, now fortune make me a King,

Fortune give me a kingdom.

Let the world report the Duke of Gloucester was a

King, therefore fortune me a King.

If I be but King for a year, nay but half a year,

Nay a month, a week, three days, one day,

Or half a day, nay an hour. Zounds, half an hour!

Nay, sweet fortune, clap but the crown on my head,

That the vassals may but once say

“God save King Richard’s life,” it is enough. (443-52)

As he ascends the throne in Shakespeare’s play, Richard says:

Thus high, by thy advice

And thy assistance is King Richard seated.

But shall we wear these glories for a day,

Or shall they last, and we rejoice in them? (4.2.3-6)

Although Shakespeare eschews the bombast, he includes a similar reflection on the transitory nature of the kingship. It hardly need be noted that there are no such musings in any of the sources.

15. Identical distinctive phrases are used several times in both plays. In True Tragedy two different characters use the phrase in good time in connection with the entrance of another person (700, 1581). In Richard III, Shakespeare used the same phrase five times in the same context, in four of them followed by the words here comes the (2.1.45, 3.1.24, 3.1.95, 3.4.21), and in the fifth by the words here the Lieutenant comes (4.1.2). Churchill adds the information that the phrase in good time does not occur in the plays of Peele or Greene, and only once, in a different context, in the entire Marlowe canon (524). The playwright of True Tragedy uses ‘no doubt’ and ‘undoubtedly’ ten times. Shakespeare uses the same words fifteen times in Richard III, but only eleven times in the balance of the canon (Churchill 523).

16. In True Tragedy, Richard says to Lovell “Keep silence, villain, least I by post do send thy soul to hell” (1928-9). In Richard III, referring to his sickly brother Edward IV, and his other brother George, he says “He cannot live, I hope, and must not die / Till George be pack’d with post horse up to Heaven (1.1. 145-6). This unusual, and now obsolete, use of the verb “to post,” meaning “to send a person in haste,” is not found in English before 1582 (OED v.1 4).

The Stanley Family Episode

Both playwrights’ depictions of the role of the Stanley family in the final months of Richard’s reign depart in similar ways from the relevant chronicle accounts. In the period following Richard’s usurpation, Henry Tudor, Earl of Richmond, attempted to gather support in France for his eventual invasion of England. Even though Richard III had appointed Thomas Stanley High Constable of England, he was suspicious of him because Stanley had married the widow, Margaret Beaufort, the Earl of Richmond’s mother, and was thus his stepfather. The chronicles report that when Stanley asked Richard if he might travel to his property to visit his family (but actually to prepare to support Richmond’s invasion), Richard refused to allow him to go unless he left his son George in court as a hostage.

In both plays, this scene is dramatized similarly, beginning with Richard’s greeting of Stanley with the phrase “What news?” In both plays, Stanley answers ambiguously. In True Tragedy, Richard persists with questions about Richmond’s plans and his strength—to which Stanley replies that he knows nothing. Richard becomes facetious:

Oh, good words, Lord Stanley; but give me leave

To glean out of your golden field of eloquence,

How brave you plead ignorance, as though you knew not

Of your son’s departure into Brittany out of England. (1515-18)

To Stanley’s ambiguous answer in Richard III, King Richard replies sarcastically:

Hoyday, a riddle! Neither good nor bad —

What need’st thou run so many miles about,

When thou mayst tell thy tale the nearest way?

Once more, what news? (4.4.459-62)

In both plays, Stanley acknowledges that Richmond is invading England to claim the throne, but protests that he is prepared to fight on Richard’s side. Richard answers that Stanley intends to fight for Richmond, and that he does not trust him. He expands on his suspicions about Stanley and says that he will not let him go. But then, in both plays, after Richard has decided against Stanley’s leaving, he changes his mind and agrees to let him go on the condition that he leave his son George as a hostage. Neither Richard’s surly rejection of Stanley’s assurances, nor his change of mind are supported in the chronicles.

Both Thomas Stanley and his brother William were present in the vicinity of Bosworth in the days before the battle, each with his own cadre of troops. Although the chronicles refer to both men and their movements, both Shakespeare and the author of True Tragedy refer only to Thomas Stanley, and they both include incidents and dialogue about him that are not found in the sources.

The sources agree that Thomas Stanley wanted to aid his stepson, the Earl of Richmond, against Richard, but was unable to do so openly for fear of the execution of his son George. They report that Stanley and Richmond met in secret before the battle, but say nothing about what they agreed to. Churchill listed the following details that were added to the dramatization of this meeting in both plays (514): Stanley hurries his answer to Richmond’s greeting, saying “In brief” in Richard III (5.8.88) and “to come briefly to the purpose” in True Tragedy (1828). In both plays Stanley describes his son George similarly, as “tender George” in Richard III (5.3.96), and as “being young and a grissell” (a young or delicate person) in True Tragedy (1848). In fact, George Stanley was a married man of about twenty-five at the time, and had taken his seat in the House of Lords as Lord Strange three years earlier (ODNB). In both plays Stanley uses the phrase “I cannot” to say that for fear of his son’s life he is unable to openly assist Richmond. In both plays he says that he will deceive Richard into thinking that he is fighting on his side. In both plays the meeting takes place at night, and Stanley warns Richmond to be prepared for battle the next day. The chronicles report that the meeting took place during the day, and are silent about the other details.

With respect to the fate of George Stanley, both plays reflect the outcome reported in the sources: on hearing that Thomas Stanley refused to join him, Richard ordered George beheaded. But his followers urged a delay on the grounds that attention was needed to the battle at hand. George survived and was eventually reunited with his father.

Finally, in the treatment of the Battle of Bosworth itself, both playwrights depart from the chronicle accounts in the same way. As Andrew Gurr pointed out (44), Shakespeare ignores the role of Thomas’s brother, William Stanley, who intervenes, according to the chronicles, with “three thousand tall men” to win the battle for Richmond at the last minute. In fact, except for a mention of him by Shakespeare in IV, v, both playwrights ignore William Stanley altogether.5 Gurr added, “In the chronicles Richard is shown winning even the hand-to-hand struggle with Richmond, until Stanley’s forces turn the tide. On stage Richard is shown losing the battle before he meets Richmond (44-5).” In both these details, Shakespeare follows True Tragedy. Thus, both playwrights have similarly modified and embellished the chronicle accounts of the role of the Stanley family.

Similarities in the Final Scenes of Both Plays

It is in the last act of Richard III and in the corresponding last four scenes of True Tragedy that the major concurrences between the two plays can be found.

The first appearance of Henry Tudor, Earl of Richmond, is strikingly similar in both plays. He enters at Scene 15 in True Tragedy and at 5.2 in Richard III—in the former accompanied by Sir James Blunt, Peter Landois, and the Earl of Oxford, and in the latter by Blunt, Oxford, Sir Walter Herbert, and unnamed others. In both cases he has been marching nearly two weeks since his landing in Wales, and is within a day or two of engaging Richard’s army at Bosworth. His opening words to his company in each play sound the same themes and use many of the same words:

Welcome dear friends and loving countrymen,

Welcome I say to England’s blissful isle,Whose forwardness I cannot but commend,

That thus do aid us in our enterprise,

My right it is, and sole inheritance,

And Richard but usurps in my authority,

For in his tyranny he slaughtered those

That would not succour him in his attempts,

Whose guiltless blood craves daily at God’s hands,

Revenge for outrage done to their harmless lives.

Then courage countrymen, and never be dismayed,

Our quarrel’s good, and God will help the right,

For we may know by dangers we have past,

That God no doubt will give us victory. True Tragedy 640-53 (emphasis added)

Fellows in arms, and my most loving friends

Bruis’d underneath the yoke of tyranny,

Thus far into the bowels of the land,

Have we march’d on without impediment;

And here receive we from our Father Stanley

Lines of fair comfort and encouragement:

The wretched, bloody, and usurping boar,

That spoil’d your summer fields, and fruitful vines,

Swills your warm blood like wash, and makes his trough

In your embowell’d bosoms–this foul swine

Is now even in the centre of this isle,

Near to the town of Leicester, as we learn.

From Tamworth thither, is but one day’s march:

In Gods name cheerly on, courageous friends,

To reap the harvest of perpetual peace,

By this one bloody trial of sharp war. Richard III 5.2.1-16 (emphasis added)

Although these words appear in the chronicle accounts of Richmond’s oration to his troops, the identical time and location of the speech, the same number and nearly identical characters present, and the similar language all suggest that the scene in True Tragedy was the model that Shakespeare used for the scene in Richard III. Furthermore, in both plays this opening speech of Richmond’s is immediately followed by supportive remarks by the Earl of Oxford and then by Sir James Blunt. Although it is known that Oxford and Blunt accompanied Richmond, neither is mentioned by any chronicler in the account of the invasion, except for Richmond’s assignment of Oxford, on the morning of the battle of Bosworth, to command the archers. In fact, all the chronicles name half-a-dozen other men as prominent in Richmond’s campaign. Thus, the presence of these particular men with Richmond at his entrance, and their responses to his speech are peculiar to the two plays.

The well-known scene in Act 5, in which Richard is visited by the ghosts of those he has murdered, is another example of Shakespeare’s extension and elaboration of a device first used in True Tragedy. It is true that ghosts appeared in other Elizabethan plays, notably in Locrine, The Spanish Tragedy, The Misfortunes of Arthur, and James IV, all of which pre-dated Richard III (Moorman 90ff.) But in this case, the particular ghost of Clarence that appeared in True Tragedy also appears (among others) in Shakespeare’s play. Although Richard’s disturbing dreams are mentioned in the chronicles, no ghosts appear in any of them. The chronicles refer to “horrible images” of “evil sprites” (Churchill 151) and “terrible devils” (Hall quoted in Bullough 3.291) that frighten Richard—but no ghosts. Furthermore, Clarence’s ghost does not merely frighten Richard, he clamors for revenge in True Tragedy (4-5, 51-5) and demands that Richard “despair and die” in Richard III (5.3.136). In Shakespeare’s play, the same imprecation is repeated by each of the nine other ghosts. As Churchill wrote, “It is not likely that the two [playwrights] hit upon the idea independently” (514).

In his soliloquy in each play, Richard expresses the same fears that the “ghosts” or “souls” of those he has murdered will exact revenge or vengeance on him. In True Tragedy:

Methinks their ghosts come gaping for revenge,

Whom I have slain in reaching for a crown,

Clarence complains, and crieth for revenge.

My nephews’ bloods, “Revenge, revenge,” doth cry.

The headless peers comes pressing for revenge.

And every one cries, let the tyrant die. (1880-5)

In Richard III, after all ten ghosts have spoken to him Richard says:

Methought the souls of all that I had murder’d

Came to my tent, and every one did threat

Tomorrow’s vengeance on the head of Richard. (5.3.205-8)

Just a few lines later, when Richard describes his “fearful dream” to Ratcliffe, he uses familiar Shakespearean imagery:

By the Apostle Paul, shadows tonight

Have struck more terror to the soul of Richard

Than can the substance of ten thousand soldiers,

Armed in proof and led by shallow Richmond (5.3.217-20)

This is clearly an echo of his line “Tush, a shadow without a substance” in True Tragedy (468) — where he uses the same imagery in a similar context of threatening troops.

Richard’s final speech on the field of Bosworth is the most obvious example of Shakespeare’s use of material from True Tragedy. In this case, he improved greatly on Richard’s opening line, in which he calls for a horse—turning it into one of the most memorable in the entire canon. Richard’s last words in True Tragedy, here converted into verse from the prose of the quarto, remind us of the Shakespeare we know, and this passage, except for the jarring first line, is probably the finest in the play:

King. A horse! A horse! A fresh horse!

Page. Ah, fly my Lord, and save your life.

King. Fly, villain? Look I as though I would fly?

No! First shall this dull and senseless ball of earth

Receive my body cold and void of sense.

You watery heavens roll on my gloomy day,

And darksome clouds close up my cheerful sound.

Down is thy sun, Richard, never to shine again;

The birds, whose feathers should adorn my head,

Hover aloft and dare not come in sight.

Yet faint not, man, for this day, if fortune will,

Shall make thee King possessed with quiet crown.

If Fates deny, this ground must be my grave.

Yet golden thoughts that reachéd for a crown,

Daunted before by fortune’s cruel spite,

Are come as comforts to my drooping heart,

And bids me keep my crown and die a King.

These are my last, what more I have to say,

I’ll make report among the damnéd souls.(1985-99)

Shakespeare’s Richard:

Rich. A horse! A horse! My kingdom for a horse!

Cates. Withdraw, my Lord; I’ll help you to a horse.

Rich. Slave! I have set my life upon a cast,

And I will stand the hazard of the die:

I think there be six Richmonds in the field:

Five have I slain today, instead of him.

A horse! A horse! My kingdom for a horse. (5.4.7-13)

In both plays it is the same cry for a horse, the same admonition to flee, the same curt rebuff, and the same declaration by Richard that he will accept the outcome of the gamble he has made. There are no such details and no such dialogue in the sources. The dramatic exchange and the language in Richard III are obviously drawn from the anonymous play. Shakespeare’s Richard indulges in no further rhetoric, perhaps because he has already, two scenes earlier, announced to his company that if he is the loser his next destination will be hell:

March on! Join bravely, let us to it pell-mell–

If not to heaven, then hand in hand to hell!(5.3.313-14)

This echoes his last words in True Tragedy:

These are my last, what more I have to say,

I’ll make report among the damnéd souls.(1998-99)

Finally, even in the manner of Richard’s death, Shakespeare has adopted the modification introduced by the author of True Tragedy. In both plays, the Earl of Richmond personally slays Richard, a detail contrary to all the sources, which uniformly report that Richard died in the general fighting. As John Jowett, the Oxford Shakespeare editor, remarked “The single combat, found also in True Tragedy, is a fiction” (354).

At the conclusion of his summary of more than thirty similarities between the two plays, only some of which have been described here, Churchill wrote: “I have endeavored to include every case in which a careful examination discovered a resemblance that cannot be accounted for by the common chronicle source of the two plays” (524). Thus, the argument is strong that Shakespeare borrowed liberally from True Tragedy in terms of structure, incident, style, and vocabulary. While he may have seen a manuscript, or even seen a performance, of True Tragedy before its printing in 1594, one inference from such borrowing is that he was its author.

Despite his extraordinary interest in True Tragedy and his comprehensive effort to elucidate it, Churchill devoted only three sentences to the identity of its author. The first sums up his attitude: “The question is of so dark a nature that the most careful investigation yields no satisfactory result” (528). One may think that a question “of so dark a nature” might attract the attention of numerous scholars. But even though Churchill detailed these extensive borrowings by Shakespeare more than a century ago, they have been ignored or dismissed as trivial by Shakespearean scholars ever since. John Dover Wilson even suggested that the obvious similarities between the two plays meant that each was based on the same lost play on the same subject by a third author (Shakespeare’s 306). But it is unnecessary to depend on an Ur-Richard III to account for two existing plays about Richard III with such remarkable similarities. To create a nonexistent play, and two imaginary dramatists, does violence to common sense. There is a better solution, and Eric Sams hinted at it in The Real Shakespeare: “. . . several of Shakespeare’s Folio plays, though none of anyone else’s, exist in two or more very different versions, including totally different treatments of the same theme. The simple and obvious explanation, now universally overlooked, is that the earlier publications were his first versions” (180). There is further evidence to support this explanation.

True Tragedy Echoed in other Shakespeare Plays

The earlier and anonymous True Tragedy shares many stylistic and lexical characteristics with canonical Shakespeare plays, especially the early ones.

Perhaps the most well-known and well-established feature of Shakespeare’s writing is his verbal inventiveness. He is credited in the Oxford English Dictionary with the introduction to the language of slightly over 2000 new words or usages (Schäfer 83), an average of about fifty per play. The author of True Tragedy display the same type of creativity. As many as eighty words and usages found in the play are described by the OED as first used by Shakespeare (forty), or other writers in 1594 or later (See Appendix). At least seven usages have not been defined by the OED.

Albert Feuillerat observed that “Shakespeare has a marked preference for the association of two words—nouns, adjectives, or verbs—expressing two aspects of the same idea and connected by a conjunction” (61), a figure of speech known as hendiadys. They are relatively rare in Marlowe and other Elizabethan playwrights (65), but more than a dozen examples, such as “doubtful and heavy,” “resolute and pitiless,” and “dull and senseless,” can be found in True Tragedy.

J. D. Wilson identified as “very common in Shakespeare” the use of the word even for emphasis at the beginning of a line (Titus xxi), such as in “Even for his sake am I pitiless” in Titus Andronicus (2.1. 162). He cited six other examples from the play, as well as three from other plays. True Tragedy contains several similar formulations, such as “Farewell, even the worst guest that ever came to my house” (580) and “even from this danger is George Stanley come” (2142-3).

David Lake, in his study of Thomas Middleton and Shakespeare, wrote: “Through all his work, Shakespeare prefers them to em and hath to has; he makes very little use of I’m (only five authentic instances outside Timon) or of Has for he has (14 authentic instances outside Timon)” (281). These same preferences are obvious in True Tragedy: them occurs sixty-three times, em never; hath eighty-two times, has three (and hast nine). Neither I’m nor Has for he has occurs at all.

In his intriguing study, The authorship of Shakespeare’s plays, Jonathan Hope counted the incidence of all forms of the words thou, thy, thine, and thee in the plays of Shakespeare, and compiled an index that reflected their use in each play. For the nine histories, the average index is fourteen (61-3). A similar calculation for True Tragedy reveals an index of fifteen.

In its use of words with the “venge” root, True Tragedy conforms with the other early Shakespeare plays in which revenge is an important motif. In Titus Andronicus there are forty-three such words; in 3 Henry VI, twenty-three; in Richard III, twenty; and in True Tragedy, twenty-nine.

Besides stylistic markers, there are frequent examples of distinctive words and phrases in True Tragedy that reappear in Shakespeare plays, especially the histories. In his death-bed scene in True Tragedy, King Edward IV uses the word “redeemer” (187). In Richard III, the same word occurs twice in the same scene (2.1.4 and 124), but is used nowhere else in the entire canon. The phrase “Lord Protector over the realm” in Scene 1 of True Tragedy occurs again six times in the three Henry VI plays (Pitcher 144).

As mentioned above, in Scene 4 of True Tragedy Richard says, “Tush, a shadow without a substance, and a fear without a cause” (468-9). The following examples attest to the dramatist’s liking for the formulation: “he takes false shadows for true substances” (Titus Andronicus 3.2.80); “Each substance of a grief hath twenty shadows” (Richard II 2.2.14); “the very substance of the ambitious is merely the shadow of a dream” (Hamlet 2.2.257-9); “since the substance of your perfect self is else devoted, I am but a shadow” (Two Gentlemen of Verona 4.2.125).

The phrase ruin and decay from Scene 3 of True Tragedy (270) is used again in Richard II (3.2. 102) and in Richard III (4.4.409) (Pitcher 143).

Jane Shore’s question about a name in True Tragedy, “O Fortune, wherefore wert thou called Fortune?” (195) is echoed in a similar context by Juliet: “O Romeo, Romeo! Wherefore art thou Romeo?” (Romeo and Juliet 2.2.33).

In True Tragedy, the word latest is used twice to mean last in the context of dying: “Outrageous Richard breathed his latest breath” (33) and “sweet death, my latest friend” (1976). This usage is echoed in both 3 Henry VI: “breath’d his latest gasp” (2.1.108), and in 2 Henry IV: “And hear, I think, the very latest counsel / That I shall ever breathe” (4.3.183-4).

In 1985 Naseeb Shaheen pointed out that a distinctive phrase in True Tragedy was repeated three times in two later Shakespeare plays (32-3). In Scene 12 one of the princes’ murderers says, “I had rather than forty pounds I had ne’er ta’en it in hand,” meaning that he wished that he had never undertaken the murder even more than he wished he had forty pounds. The identical formulation in a different context occurs twice in Twelfth Night, once referring to the same forty pounds (5.1.177-8) and once to forty shillings (2.3.20-1). In The Merry Wives of Windsor, Slender says, “I had rather than forty shillings I had my book of Songs and Sonnets here” (1.1.183-4), a reference to Richard Tottel’s collection of poems published in 1557.

In his analysis of Edward III as a Shakespeare play, Kenneth Muir considered the many examples in it of language that is paralleled in canonical Shakespeare plays. He wrote, “Of course, even if these parallels are valid, Shakespeare might conceivably be echoing and improving on a play by another dramatist, in which perhaps he had himself acted. But if this were so, it would be unique in his career . . .” He also referred to “Shakespeare’s usual custom . . . to refine on a passage he had written earlier” (47).

The evidence presented here demonstrates that Shakespeare was familiar with True Tragedy, and incorporated numerous words and phrases, stylistic elements, and dramatic details—and even errors of fact—into his Richard III. It is also apparent that many of these words and phrases, stylistic elements, and lexical characteristics found in True Tragedy can be found throughout the Shakespeare canon, especially in the earlier plays. The conclusion can hardly be avoided—The True Tragedy of Richard the Third is a Shakespeare play.

Evidence for de Vere’s Authorship

For those who are convinced by the overwhelming evidence that Edward de Vere, the 17th Earl of Oxford, wrote the plays of Shakespeare, his authorship of True Tragedy follows from the evidence presented here. Even a cursory perusal of de Vere’s letters and poems reveals many of the linguistic markers found in True Tragedy—hendiadys, alliteration, subject-verb disagreements, unusual words, archaic words, etc. One particular example echoes the phrase “a shadow without a substance“ mentioned above. In a 1581 letter, Oxford wrote, “But the world is so cunning as of a shadow they can make a substance, and of a likelihood a truth” (Chiljan 32).

Another example from True Tragedy is Jane Shore’s remark about her husband’s reaction to her relationship with Edward IV: “Yea, my own husband knew of my breach of disloyalty, and yet suffered me, by reason he knew it bootless to kick against the prick” (1025). Oxford’s use of this proverb, meaning “to struggle against fate,” in a January 1576 letter to Lord Burghley is cited in Wilson’s Oxford Dictionary of English Proverbs as one of only five sixteenth century occurrences (421). Writing from Siena, Oxford resorted to Italian to express his frustration: “ . . . and for every step of mine a block is found to be laid in my way, I see it is but vain, calcitrare contra li busi . . . “ (Chiljan 23), literally “to kick against blows.”

Certain external evidence supports the association of True Tragedy with Shakespeare and with Edward de Vere. Between 1594 and 1612, its printer and publisher, Thomas Creede, printed Richard III four times, as well as four other Shakespeare plays, three of which bore no author’s name. (He also printed three non-Shakespearean plays with Shakespeare’s name or initials on them.) During the 1590s, he printed or registered ten plays that were clearly or probably the property of the Queen’s Men, the playing company named on the title page of True Tragedy (Pinciss 323). The Queen’s Men company is well-known for its alleged association with Shakespeare and his plays, but it also had a connection with the Earl of Oxford. When the company was assembled in 1583, leading players were taken from three or four existing companies that had all recently appeared at Court, including one sponsored by the Earl of Oxford (Chambers, Facts 1.28; Stage 2.5).

The Thirteenth Earl

The most convincing evidence of Oxford’s authorship is found in the portrayal of the historical John de Vere, 13th Earl of Oxford, as the future Henry VII’s principal supporter in True Tragedy. It is well known that the 13th Earl was one of the leading Lancastrian noblemen who fought on the side of Henry VI against the Yorkists. After years of opposition, he was finally captured, attainted, and then imprisoned at Hammes Castle near Calais for more than ten years until he escaped in early 1485, assisted by his jailer, James Blunt (Seward 216, 297). Oxford and Blunt joined Henry Tudor, Earl of Richmond, in France, and accompanied him on his invasion of England in August 1485. Oxford commanded the forward troop of archers at Bosworth, and was later rewarded handsomely by the victorious Henry VII.

Several of the chronicles describe the 13th Earl as a leading supporter and close friend of Henry Tudor. But they do not mention him in connection with Henry‘s invasion until the actual Battle of Bosworth, when Henry gives him his command. However, in each of the three scenes in which Henry Tudor appears, the author of True Tragedy has placed the Earl of Oxford at his right hand, and made him the leading spokesman for his supporters. In the play, Richard III himself speaks of Oxford, something he does not do in the chronicles. Here is his reaction when he is told that Oxford and Blunt have escaped their prison in Brittany, and joined the Earl of Richmond:

Messenger stay! Hath Blunt betrayed?

Doth Oxford rebel and aid the Earl Richmond?

May this be true? What? Is our prison so weak,

Our friends so fickle, our ports so ill looked to,

That they may pass and repass the seas at their pleasures?

That every one conspires, spoils our conflex,

Conquers our castles, and arms themselves

With their own weapons, unresisted?

Oh villains, rebels, fugitives, thieves, how are we betrayed,

When our own swords shall beat us,

And our own subjects seek the subversion of the state,

The fall of their Prince, and sack of their country — of his!

Nay, neither must nor shall, for I will army

With my friends and cut off my enemies,

And beard them to their face that dares me;

And but one, aye, one — one beyond the seas that troubles me.

Well, his power is weak, and we are strong;

Therefore I will meet him with such melody

That the singing of a bullet shall send him merrily

To his longest home. Come, follow me.(1624-38)

It is after this speech in Scene 14 that the future Henry VII strides onto the stage for his first appearance in True Tragedy. It is the Earl of Oxford and James Blunt who accompany him, just as they do in Richard III. But thereafter, the two plays diverge, Oxford’s significant role in True Tragedy being reduced to only two lines in Richard III. After Henry’s opening speech in True Tragedy, it is the Earl of Oxford who responds first with assurances that he will fight for his “cousin Richmond” until he is crowned King. After Henry promises to root out corruption and tyranny if he is successful, it is the Earl of Oxford who replies again that he will not be frightened or deterred by the vicious acts of Richard. And in the last scene of the play, after Richard has been slain, it is the Earl of Oxford who vows “perpetual love” to Henry and showers him with compliments, while making classical references to Cicero, Caesar, Hector, and Troy. Finally, after Thomas Stanley, presents the crown of England to his stepson, Henry, it is the Earl of Oxford who shouts, “Henry the Seventh, by the grace of God, King of England, France, and Lord of Ireland; God save the King,” a proclamation repeated by the rest of the cast.

In another instance, the playwright emphasizes the closeness of the two men by giving to Oxford the role of gently chiding Richmond for his unexplained disappearance two nights before the Battle of Bosworth. The chronicles report that Richmond became separated from his company in the darkness, and found himself alone and unable to locate any of his soldiers. He spent the night incognito in a small village, and by good luck found his army early the next morning. He explained his mysterious absence to his greatly-relieved officers with a story about visiting some “prevy frendes and secret alies” (Bullough 3. 290). No other person is mentioned in connection with this incident. But in Scene 16 of True Tragedy, when only Oxford and Richmond are on stage, Oxford remarks, “Good my Lord, have a care of yourself. I like not these night walks and scouting abroad in the evenings so disguised, for you must not, now that you are in the usurper’s dominions, and you are the only mark he aims at; and your last night’s absence bred such amazement in our soldiers that they, like men wanting the power to follow arms, were on a sudden more liker to fly than to fight” (1810-16). Richmond responds by repeating his affection for Oxford and asking him to excuse his behavior. There is no historical basis for Oxford’s role in this dialogue; it has been arbitrarily assigned to him by the playwright.

In all, the 13th Earl of Oxford speaks forty lines in True Tragedy, a larger role than any Earl of Oxford has in any Elizabethan play. He is repeatedly referred to in laudatory terms: “good Oxford,” the valiant Earl of Oxford,” “this brave Earl.” When Henry assigns the Earl his position at the Battle of Bosworth, he addresses him as “my Lord of Oxford, you as our second self.” After the battle, the victorious Henry, after thanking “his Deity,” says, “worthy Oxford, for thy service shown in hot encountering of the enemy, Earl Richmond binds himself in lasting bonds of faithful love and perfect unity.” Except for the reference to him on the night before the Battle of Bosworth, none of this is reported in the chronicles. It has all been inserted by the anonymous author.

A reasonable explanation for this anomaly is that the author of True Tragedy was one of the 13th Earl’s successors to the Oxford Earldom—one who was known as both a poet and a playwright. Edward de Vere’s keen interest in history, both ancient and recent, was noted by others when he was no older than fourteen.6 As a young child he lived with, and was tutored by, Sir Thomas Smith, one of England’s greatest scholars, and the owner of an extensive library (Hughes 24). The most obvious historical sources for the play—the chronicles of Polydore Vergil, Edward Hall and John Hardying, as well as several others— are found in a list of volumes in Smith’s library made in 1566, only a few years after de Vere’s residence in his household (Strype 276-7). If de Vere were the author, he would have been in an ideal position to make use of family records or an oral tradition to dramatize the role of the 13th Earl in the series of events that put the first Tudor on the throne of England. A story of such importance, only eighty to ninety years in the past, might still be recounted by people in his household at Hedingham Castle, or in his circle of acquaintances, who had known the participants.7 Besides the fact that the 13th Earl himself lived until 1513, well within the lifetime of someone alive in 1560, there is further reason to believe that those living in and around Hedingham Castle would have had a particular interest in the story of Richard III.

In 1471, after the disastrous Battle of Barnet, in which Edward IV defeated the forces of the Lancastrian Henry VI, John de Vere, the twenty-eight-year-old 13th Earl of Oxford, fled to Scotland and then to France. His mother, Elizabeth, the widow of the executed 12th Earl, was confined by Edward IV to Bromley Prior at Stratford-le-bowe, outside London. Edward then granted all of John de Vere’ s property, including Hedingham Castle, to his own brother Richard Plantagenet, later Richard III. The following year, Richard’s henchmen kidnapped the dowager Countess Elizabeth, and bullied her into signing over to him all the real property she held in her own name, including the manor at Wivenhoe (Seward 216-17). After Henry Tudor’s accession to the throne in 1485, the property of the 13th Earl was restored to him by Act of Parliament, but it took another ten years and another Act before he obtained return of his mother’s property. The dramatic story of the loss of the entire de Vere estate to Richard Plantagenet, and the heroic acts that led to its restoration, would have been routinely told in the de Vere household throughout the sixteenth century.

In Shakespeare’s play, Richard III, the Earl of Oxford is a member of the cast, but speaks only two lines (5.2.17-8), which are attributed to him only in the Folio version. We can only guess that the dramatist reduced his ancestor’s role so drastically in his revision for the same reason that he chose to conceal himself behind a pseudonym for the rest of his life. De Vere later became a skilful and prolific writer of history plays, but as a young man, especially one so recently bereft of his father, he might have had an understandable urge to draw attention to the deeds of one of his most heroic ancestors, and evidence for the date of the play suggests that he was very young indeed.

The Date of True Tragedy

Fully as important as the identity of the author of True Tragedy is the date of its composition. The evidence consists of several topical references in the play, as well as certain stylistic elements and dramatic devices. The most significant topical references occur in the last scene, which ends with a wooden description of the deeds of Henry VII, followed by those of Henry VIII, Edward VI, and Mary Tudor. The final words in the play are a twenty-five-line encomium to Queen Elizabeth that appears to have been written for direct delivery to her from the stage. It begins with general words of praise about her “wise life” and “civil government,” which are followed by the lines:

And she hath put proud Antichrist to flight,

And been the means that civil wars did cease.

It was commonplace for the Protestants of Elizabethan England to refer to Catholic nations and their rulers, among all other things Catholic, as the Antichrist. E. K. Chambers suggested that the line about the Antichrist “may pass for . . . a mention” of England’s victory over the Spanish Armada in 1588 (Elizabethan iv, 43-4).8 However, the playwright had, in a previous passage, already mentioned the leading Catholic monarch in Europe, and the instigator of the Armada, King Phillip II of Spain, and had described him merely as the husband of Queen Mary. Any reference to Elizabeth’s most stunning military victory in the immediate years after 1588 would have merited more than a single line in a list of her achievements. It is much more likely that these two lines refer to Elizabeth’s invasion of Scotland, and the expulsion of the French forces there, in the second year of her reign.

In late 1559, Scottish Protestants began a rebellion against their French Queen Regent, Mary of Guise, mother of the sixteen-year-old Queen, Mary Stuart, then living in France with her husband King Francis II (Guy 264-5). Mary of Guise was the sister of the powerful de Guise brothers, who had sent her to Scotland in her daughter’s stead to govern the country while they schooled the young Mary in the elements of statecraft. As a foreign Catholic ruler in a largely Protestant country, Mary maintained a substantial cadre of French troops in and around Edinburgh Castle to protect herself. When the Scots, after several months of fighting, failed to dislodge her troops from their stronghold at Leith, the port of entry for Edinburgh, they asked for Queen Elizabeth’s help.

Elizabeth hesitated at first, but then, in December 1559, sent fourteen ships into the Firth of Forth to blockade the French and prevent their reinforcement. The following March she dispatched an army of nearly five thousand troops across the border under Lord William Grey, who began a prolonged siege of Leith. After an initial setback, the English prevailed, and within three months William Cecil was in Scotland negotiating the Treaty of Edinburgh, a pact that ended the civil war and expelled French troops from Scotland permanently (Guy 266, Neale 87-99). Thus, Elizabeth was aptly described as the monarch who was “the means that civil wars did cease” and who “put proud Antichrist to flight.”

Another passage in the encomium reads

‘Twere vain to tell the care this Queen hath had,

In helping those that were oppressed by war,

And how her Majesty hath still been glad,

When she hath heard of peace proclaim’d from far.

Geneva, France, and Flanders hath set down,

The good she hath done, since she came to the crown.

These lines appear to refer to events in the first year of the so-called “French Wars of Religion” between the French Protestant Huguenots and the Catholic government—the Royalists—that began in March 1562 and continued intermittently until 1580. For both religious and political reasons, Elizabeth supported the French Protestants against the Royalists. In the fall of 1562, she signed the secret Hampton Court Treaty with the Huguenot leader Louis de Bourbon, Prince of Condé. In it she agreed to send him six thousand troops and loan him £30,000 in return for which the English would occupy the French ports of Le Havre and Dieppe. Within a few months, however, the Huguenots suffered several military defeats and de Bourbon was captured by Francis, Duke of Guise, leader of the Royalist forces. In February 1563, Francis himself was assassinated, and the next month the two sides agreed to a truce—the Peace of Amboise (Guy 267). The final two lines above refer to Elizabeth’s policy of support for Protestants abroad, which earned her the gratitude of the Huguenots in France, the Protestants in Flanders, and the Protestant city of Geneva.

Another passage contains several traceable references:

The Turk admires to hear her government,

And babies in Jewry, sound her princely name.

All Christian Princes to that Prince hath sent,

After her rule was rumored forth by fame.

The Turk hath sworn never to lift his hand,

To wrong the Princess of this blesséd land.

Lines 1, 3, and 4 in this passage apparently refer to the greetings and congratulations sent to Elizabeth by foreign leaders at the time of her accession: “After her rule was rumored forth by fame.” The State Papers of the first six months of her reign contain records of such greetings from Henry II of France, the Holy Roman Emperor Ferdinand I, the King and Queen of Portugal, the Queen of Denmark, the King of Sweden, and many lesser notables (CSP i, 32-3, 51, 53, 72, 90-1, 103, 109, 167-8). Line 2 in this passage refers to the identification of Elizabeth at the time of her coronation as the English Deborah—the counterpart of the Biblical Deborah, the charismatic woman who was celebrated in the Book of Judges as the protector and preserver of the Israelites (Guy 250-1). Her accession was equated with the Israelites’ victory over the idolatrous Canaanites, directed by the divinely-inspired Deborah, as recounted in chapters four and five of the Book of Judges (Meyers 66-7).

At the time of Mary Tudor’s death in 1558, the morale of the English and the fortunes of their country were at a low ebb after five years of religious turbulence and ineffective rule by the Catholic Queen. The coronation of the new Queen in January 1559 was the occasion for much celebration and rejoicing by the London populace. Along the route of her coronation parade, the Queen was taken past five “pageants” or tableaux, each of which offered an encouraging, instructive, or complimentary message. The final pageant depicted a robed and enthroned Queen, shaded by a palm tree and accompanied by a sign reading “Debora the judge and restorer of the house of Israel. Judges 4” (Arber iv, 386-7). This was a clear identification of Elizabeth as the Biblical Deborah, and of the English nation as the beleaguered Israelites of the Old Testament.9 Jews were banished from England in 1290, and were nearly invisible during the sixteenth century, with only a few notable exceptions. There was no event during Elizabeth’s reign that would have evoked celebration among the actual Jewish residents of England. The line clearly points to a similarity between events in England in 1558 and the story of the Biblical heroine who rallied her followers against unbelievers, and helped them unite in their practice of the true religion.

The final couplet in this passage reads

The Turk hath sworn never to lift his hand,

To wrong the Princess of this blesséd land.

This is the most difficult reference in the encomium to trace. During the Reformation, it was common for both Protestants and Catholics to refer to each other as “Turks,” that is, non-believers in the true faith. Both John Wycliffe and the Pope were called “Turks” by their opponents. In the literature of the period, the term was a standard synonym for a cruel, barbarous, and uncivilized person, and Falstaff even referred to Pope Gregory XIII as “Turk Gregory” in 1 Henry IV.10 In general, however, the term referred to the government of the Ottoman Empire at Constantinople, and more particularly to the head of that government—the Sultan. It is evident that this is the intended reference in the couplet.

The most notable Sultan of the sixteenth century was Suleiman I, who was called “the Magnificent” in the West, but who was also the foreign ruler most feared by “Christian Princes.” In the forty years following Suleiman’s accession in 1520, his Ottoman army—larger than any in the West and seemingly unstoppable—advanced deep into southeastern Europe on four different occasions, and swept aside Christian armies in the name of Islam (Green 384-5, 486). The major power defending Europe against the Ottoman Turks was the Holy Roman Empire, which was also carrying on an intermittent war with France. This led to an alliance of sorts between the Sultan and the King of France, an alliance that was viewed with alarm by the English.

In the couplet just quoted, the playwright might be referring to one of the following four events:

1. In his greeting referred to in the line “The Turk admires to hear her government,” Sultan Suleiman may have sought to reassure the new Queen that he had no military designs on her country.

2. In February, 1559, Suleiman and the Holy Roman Emperor, Ferdinand I, signed a three-year truce in which the latter agreed not to aid Spain against France, and to pay certain sums annually to Suleiman, in return for which the former agreed to halt his aggression against the Empire. This was reported in March in a letter to Queen Elizabeth from Christopher Mundt, her agent in Germany (CSP i, 191), and in June in a letter to William Cecil from Nicholas Throgmorton, the Queen’s ambassador in France (CSP i, 303). Such an agreement might have been interpreted in London as amounting to a non-aggression promise to Queen Elizabeth.

3. Three years later, Suleiman and the Emperor came to a similar agreement—the Peace of Prague—in which Suleiman agreed to forgo further attacks for another eight years (Cambridge 2, 587).11 In this treaty, Suleiman also promised safe passage and courteous treatment of “all Christians” throughout his territory (Knolles 790). Cecil was also notified of this agreement (in June, 1562), and might also have interpreted it as a non-aggression promise (CSP v, 109, 134).

4. In February, 1563, Queen Elizabeth’s Ambassador in France, Sir Thomas Smith, wrote to the Privy Council (from Blois) about a planned meeting between him, a French diplomat, the Emperor’s Ambassador, and “the Turk’s Ambassador” (CSP vi, 140). This was at a time when Huguenot and Royalist forces were fighting in various parts of France. Since the Turks were allied with the Royalists, and England was aiding the Huguenots, the Turkish Ambassador may have used the occasion of the meeting to assure Smith that the Sultan had no intention of attacking his country. There is no report in the relevant State Papers about the outcome of the meeting, but it may have been reported in another piece of correspondence that is lost or remains undiscovered.

Admittedly, hard evidence is lacking for this specific diplomatic communication from Sultan Suleiman to Queen Elizabeth, and the possibilities cited are speculative. But they are reasonable speculations that are consistent with the accompanying historical evidence, and consistent with the dates derived from the other references in the encomium.

The final four lines of the encomium hint at the death of Queen Elizabeth:

For which, if e’er her life be ta’en away,

God grant her soul may live in heaven for aye.

For if her Grace’s days be brought to end,

Your hope is gone, on whom did peace depend.

These lines may refer to the Queen’s near-fatal illness with smallpox in October 1562. For two weeks she lay near death, and at one time gave instructions from her bed to Cecil and the other Privy Councilors about what should be done if she died (Read 265-6). Without question, this episode would have had a profound impact upon William Cecil, whose household in the Strand Edward de Vere had entered only the previous month.

Although most commentators place the composition of True Tragedy in the late 1580s or early 1590s, only one has made a serious attempt to date the play from internal evidence. In 1921 Lewis F. Mott analyzed the references in the encomium and concluded that True Tragedy was written in late 1589 and first performed at court that December by the Queen’s Men, the acting company named on the quarto’s title page (71). He asserted that the congratulatory messages sent to Queen Elizabeth, and the reference to her defeat of the Antichrist, all had to do with England’s victory over the Spanish Armada in 1588 (66). He claimed that the playwright “unquestionably had before him” a copy of Richard Hakluyt’s Principal Navigations, which was published in November 1589, and contained the texts of numerous letters that passed between Queen Elizabeth and the Turkish Sultans. Most of these pertained to assurances of favorable treatment and grants of safe passage by each monarch for the travelers and traders of the other.

However, as stated above, the promise of the Turk referred to in the couplet is not about trading privileges or diplomatic immunity; it is a pledge not to aggress against Elizabeth or her country. In fact, permission to trade throughout Turkish territory was granted by Suleiman I to the Englishman, Anthony Jenkinson, as early as 1553 (Hakluyt iii, 36-8). In 1579 William Harborne, the first government-sanctioned English trader in Turkey, arranged an exchange of letters between Queen Elizabeth and Sultan Murad III that resulted in an extensive “charter of privileges” for all English merchants in Turkey (Hakluyt iii, 51-6). The Queen licensed the Levant Company in 1581, and the next year made Harborne her deputy and agent at the Sultan’s court (Hakluyt iii, 64-72, 85-7). The Company continued to enjoy this privileged status throughout Elizabeth’s reign with only occasional interruptions. Therefore, even if it were a trade agreement that was referred to in the play, there was no particular event or occasion in the late 1580s that would merit such a reference in a catalogue of her accomplishments.

Mott also attempted to draw a connection between the line “And been the means that civil wars did cease” and events in England in 1589 by claiming that “The conflict between the peace party and the war party at Elizabeth’s court is well known” (69). But to call this political conflict “civil wars” is to do violence to the phrase. He is on firmer ground with his claim that “The good she hath done” with respect to France referred to the contingent of 4000 men Elizabeth sent to aid Henry of Navarre when he became King of France in August 1589 (70-1). Although there exists a letter of thanks from Henry, Mott acknowledged that this alliance deteriorated into a quarrel between the two monarchs by February 1590. He also admitted that there are only “vague indications” of “the good she hath done” for Geneva and Flanders in this time period. Finally, Mott acknowledged that “Diligent search has failed to connect the ‘babes in Jewry’ with any specific act of Elizabeth” (69). As shown above, the identification of Elizabeth as a modern-day Deborah at the time of her coronation fully explains the line. A reasonable conclusion, therefore, is that the evidence connecting the encomium’s references to events and circumstances in the early 1560s is stronger and more consistent than Mott’s claimed connections to events and circumstances in late 1589.

The final word to be said about the encomium to Elizabeth at the end of True Tragedy is that it bears a conspicuous resemblance to a comparable one at the end of another play with circumstantial connections to Edward de Vere. The play is King Johan, by the Protestant convert and dramatist John Bale (1495-1563), who entered the service of John de Vere, 15th Earl of Oxford, in the early 1530s (Harris 75). Among the more than fourteen plays that Bale wrote for the playing company that de Vere patronized was the earliest version of King Johan (1534), which has been identified as the first “extant play on actual British history” (Harris 75; Ribner 35, 65), and the first play in which a King of England appeared on stage (Harris 64).

Scholars agree that Bale revised King Johan several times over his lifetime, the last between September 1560 and his death three years later (Pafford xix). The twenty-two lines of praise for Queen Elizabeth that he added at the end of the play have become associated with her visit to Ipswich in August 1561 because the single surviving copy was found “among some old papers, probably once belonging to the Corporation of Ipswich” (Harris 71, 104). These lines, apparently written for a performance before the Queen herself, may have been the model for the twenty-six similar lines at the end of True Tragedy that have the same tone and subject matter, and include many of the same words. In both are asseverations of the Queen’s wisdom, her role as a lamp or light for other rulers, her mission of peace in England in the service of God, her conquest of the Antichrist, as well as the same admonition to pray for her long life. It is not difficult to imagine that King Johan was performed by the 16th Earl’s own company during the Queen’s four-day visit to Hedingham Castle, only twenty-five miles from Ipswich, in August 1561 (Ward 12). And it is hard to imagine that the eleven-year-old de Vere would not be present to meet the Queen and see the play.

The Thomas Churchyard Connection

Another clue to the date of True Tragedy can be found in Scene 11, in which Edward IV’s former mistress, Jane Shore, bemoans her fate and her treatment at the hands of Richard III. After a long conversation with her, Lodowick, a servant of Lord Hastings, remarks:

Therefore, for fear I should be seen talk with her, I will shun

her company and get me to my chamber, and there set down

in heroical verse, the shameful end of a King’s concubine, which

is no doubt as wonderful as the defoliation of a kingdom. (1076-79)

This is an obvious reference to the narrative poem by Thomas Churchyard (1520?-1604) that was first published in 1563 in the third edition of A Mirror for Magistrates—“Howe Shores Wife, Edwarde the Fowerthes Concubine, Was by King Richarde Despoyled of All Her Goodes, and Forced to Do Open Penance.” No other poem was published in England about the life of Jane Shore before 1593 (Harner 496-7), and “Shore’s Wife” is the obvious source of the language and detail used to portray her in the play.