by Richard F. Whalen

(Editorial Note: This article was originally published in The Oxfordian, vol. 8, pp. 7–24 (2005), slightly revised and republished in Shakespeare Beyond Doubt? (2013) (ch. 12, pp. 136–51), and republished here on the SOF website, Feb. 15, 2018.)

Today’s Stratford monument is the defining image of William Shakspere of Stratford-upon-Avon as the alleged author of Shakespeare’s poems and plays. In the church where he’s buried, it shows a writer with pen, paper and writing surface (a cushion of all things). The plaque on it says it’s for “Shakspeare,” although without a first name. Thus, according to the Stratfordian storyline, the monument was erected to honor the world’s greatest writer, namely the man from Stratford. But this monument is a fraud, a “monumental” fraud. It is not the original, nor does its effigy resemble the original. The cumulative power of the evidence against the authenticity of today’s monument is clear and convincing.

The principal witnesses against its authenticity are a respected antiquarian who left an eyewitness description of the original monument, an eighteenth-century artist whose engraving is the first to depict a writer in it, and a famous painter who called it “a silly smiling thing.” The evidence includes the letters of a Stratford curate who protests far too much about how he “refurbished” it, his mention of a mysterious “Heath the carver” whose role has not heretofore been sufficiently recognized, and the records of those who at various times complained of the wear and tear on a monument that today looks like it has survived over four centuries untouched by time. Underlying the faulty rationale of orthodoxy is a mistaken standard of accuracy.

There are two fundamental issues: first, whether the antiquarian William Dugdale was accurate when, in 1634, he sketched the effigy in the monument as a dour man with a down-turned moustache clutching a large sack — not a writer with pen and paper, as in today’s monument — and if so, how the sack-holder became a writer. If Dugdale and his engraver, Wenceslaus Hollar, are to be believed, Oxfordians have a persuasive argument that William Shakspere of Stratford was not the great poet-dramatist, while Stratfordians and their biographers have a major problem. Although the controversy began in earnest around 1900, evidence and analysis acquired since then all tends to confirm that today’s monument is not the original, but the result of a long series of alterations.

Most Stratfordian biographers avoid the issue, among them: Stephen Greenblatt (2004), and notably in his collected works of Shakespeare for Norton (1997), Michael Wood (2003), Park Honan (1998), and Stanley Wells (1995). None mentions Dugdale’s sketch or the engraving that Hollar made from it for Dugdale’s book, even though Dugdale’s sketch is the earliest eye-witness evidence of what the monument looked like. Dugdale was also the first to transcribe the abstruse epitaph on the monument. Stratfordian biographers, however, rarely try to explain what it means, even though it, too, is primary source evidence suggesting what contemporaries thought about the man for whom it was written and engraved. Evidently, they do not want to confront what the effigy and the epitaph might reveal about his identity.

A few Stratfordian scholars have recognized and struggled with the problem. The first was probably the antiquarian John Britton. In 1816, he summarily dismissed Hollar’s engraving in Dugdale’s book as “tasteless and inaccurate” (13). In 1853, J.O. Halliwell-Phillipps called it “evidently too inaccurate to be of any authority” (Greenwood Problem 247 fn. 1).

Inaccurate compared to what?

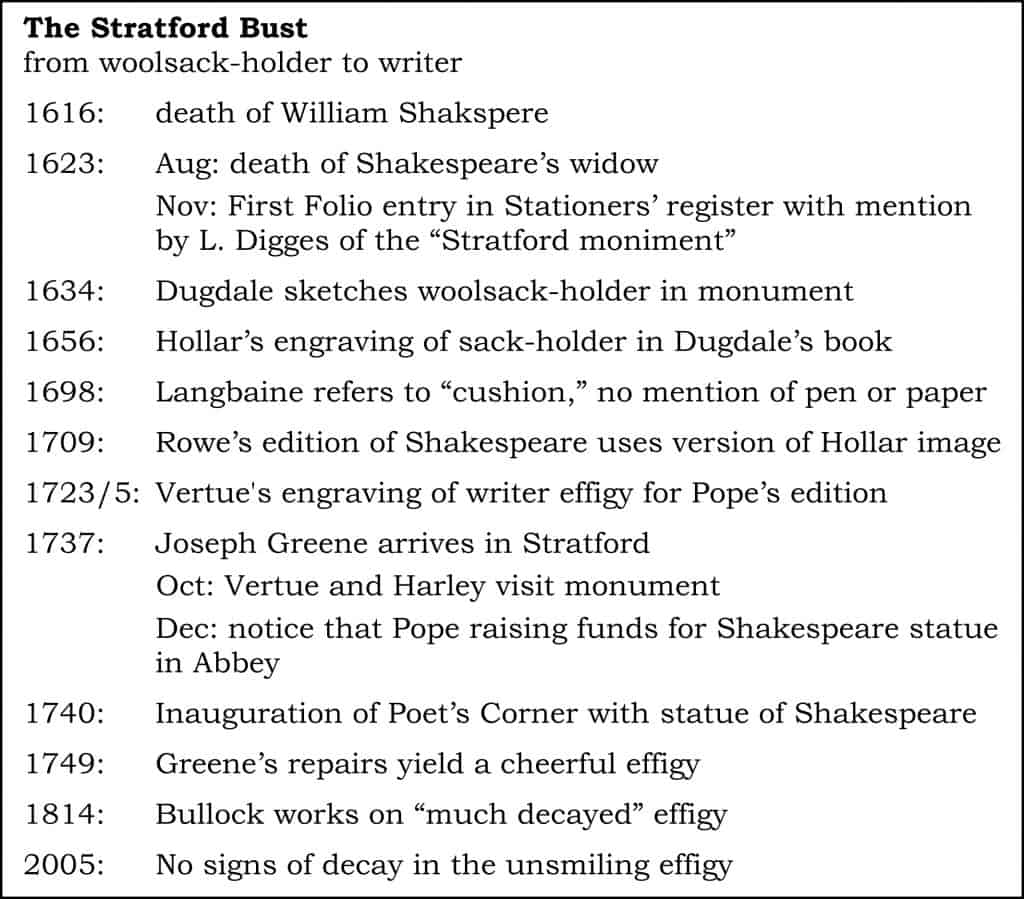

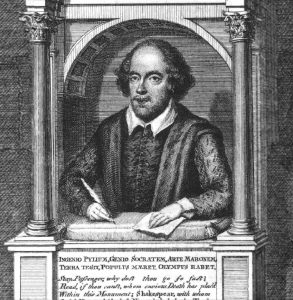

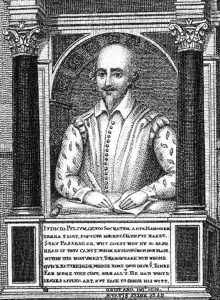

Since those who allege inaccuracy have no hard evidence such as a photograph or explicit description of what the monument looked like in the early 1600s, their standard of accuracy, though unstated, can only be the effigy as per the 1800s figure, essentially the one we see today. That effigy, however, cannot be the standard of accuracy for something created two centuries earlier. Dugdale’s sketch, the earliest eye-witness evidence (Fig. 1), and Hollar’s engraving, based on Dugdale’s sketch (Fig. 2), are primary-source historical evidence depicting what the original effigy looked like, i.e., a man with a sack. No pen. No paper. No cushion.

Charlotte Carmichael Stopes, a Stratfordian, was the first to analyze the evidence in detail. A dogged researcher, she published dozens of articles and several books on Stratford and its famous son. In 1904, she argued that Hollar’s engraving was an accurate depiction of the dramatist when he was old and near death, “a tired creator of poems, exhausted from lack of sleep … weary of the bustling London life” (114). The effigy, she said, was later fundamentally changed to depict a writer in his prime, “necessarily something very different from the original” (113, 120). To her dismay, she found herself caught between the Baconians, who had seized upon the Hollar effigy as evidence against the Stratford man, and her Stratfordian colleagues, who said she failed to understand that Dugdale and Hollar were mistaken and that the original monument depicted a writer (115). Ten years later she would also be the first scholar to see the original sketch at the Dugdale ancestral home, where it remains. She reprinted her 1904 article in her 1914 book, where she reported on additional research in Stratford and that Dugdale’s sketch and others in his diary show that “he was very careful as to significant details” (123).

Biographer Henry Lee rejected Dugdale and Stopes. After seeing Dugdale’s drawing among his papers he wrote that “it differs in many details, owing to inaccurate draughtmanship, from the present condition of the monument” (496–97). Like others who call Dugdale inaccurate, he failed to explain how today’s monument could act as a standard of accuracy for something created before 1634, when Dugdale sketched it. Lee dismisses Stopes (522–23): “There is very little force in her argument to the effect that Dugdale’s sketch faithfully represents the original form of the monument, which was subsequently refashioned out of all knowledge.”

Out of all knowledge?

Marion H. Spielmann, who wrote widely on art, was the only Stratfordian to address the authenticity problem head-on. In a slim, vitriolic volume published in 1924, he argued at length and with examples that both Dugdale and Hollar were unreliable and mistaken. He maintained that both made errors in other works and that Dugdale was “victimized both by his helpers and his artists” (16). He claims that Hollar’s workshop, not Hollar himself, may have produced the engraving of the Stratford monument, and he notes errors in three other Hollar engravings (1819). The engraving of an equestrian statue shows the horse with the wrong forefoot raised. In Dugdale’s Antiquities, the Clopton monument in the Stratford church has several details reversed or omitted, while the Carew monument engraving reverses the positions of the husband and wife. (Lee and Stopes had noted that the Carew sketch was not among Dugdale’s papers, indicating that someone else had drawn it.) None of the errors, however, changed what the subject looked like: a horse and the prone figures of wife and husband. The Dugdale sketch and the Hollar engraving of a sack-holder, whether or not exact in every detail, stand together as solid evidence of what the effigy actually looked like in 1634.

Spielmann found a determined critic in Sir George Greenwood, barrister, member of Parliament and an original thinker determined to make the public aware of the case against Stratford. In his 1908 book, Greenwood agreed with Stopes that Dugdale-Hollar represented the original effigy, but not that it represented Shakespeare as weary and near death. He commended her attempt to explain the discrepancy, but concluded: “It seems absolutely certain that this Stratford bust … is in reality not the original bust at all,” adding that “the whole thing is changed” (Problem 245–46).

Returning to the issue in 1925 with The Stratford Bust and The Droeshout Engraving, Greenwood noted the “vast amount of discussion and disputation” about the bust. He argued again that the Dugdale drawing, which he had seen by then, “is absolutely unlike the effigy as it exists today” (10). He critiqued Spielmann at length, correcting, for example, Spielmann’s claim that the £12 10d paid to a local painter, John Hall, was too little for a major renovation of the effigy, and noted that the moustache on today’s bust did not come into fashion until decades after Shakspere’s death (15–17, 21–22). Point by point, Greenwood rebutted Spielmann, who remained silent.

In 1930, E.K. Chambers alleged, in an uncharacteristic overstatement (probably based on a reading of Spielmann), that other illustrations in Dugdale’s book also “completely misrepresent the originals.” Citing Stopes and Greenwood, he concludes, “But the whole theory seems to me a mare’s nest [and] incredible that the monument should ever have resembled Dugdale’s engraving” (2:185). He describes the Hollar engraving well enough, but does not show it.

The importance of the Dugdale/Hollar effigy drew the attention of Oxfordians later in the century. Dorothy Ogburn and her son Charlton published Hollar’s engraving in their 1962 book, but with little analysis. Briefly they cited Greenwood’s rejection of today’s bust as authentic and suggested that non-Stratfordians must find it almost impossible to think of it as depicting Shakespeare (107, 115). Twenty years later, Ogburn Jr. devoted just two of the 800 pages of his biography of Oxford to Dugdale, Hollar and Rowe, concluding, “There seems scant room for doubt that the subject of the original sculpture was not a literary figure but a dealer in bagged commodities” (212–13). Both books included the Hollar engraving.

One of the very few Stratfordian scholars to publish the Hollar engraving was Professor Samuel Schoenbaum, the leading “Shakespeare” biographer in the later twentieth century. In 1975 he allowed that the engraving of the sack-holder is “perplexing rather than helpful” and hard to reconcile with today’s monument. But he concluded rather lamely that it is “authentic enough” (Life 255). In the compact 1987 edition, Schoenbaum added a provocative (parenthetical) possibility to his text: “A comparison of the engraving [by Hollar] with the drawing [by Dugdale] — perhaps still extant — on which it is based might be revealing” (313). The drawing, of course, was extant.[1]

Dugdale and Hollar

It was Sir William Dugdale of Warwickshire, author of the mammoth Antiquities of Warwickshire (1656), who provides us with what is undeniably the earliest authentic image of the effigy. The prolific antiquarian sketched the monument during a visit to Stratford on July 4, 1634, eighteen years after the death of William Shakspere (Lee 484, 522), a period when many residents of Stratford would have had living memories of their neighbors, the Shaksperes. Dugdale’s sketch, found among his papers, shows a man of dour visage, with arms akimbo, holding a large sack of wool to his midsection in nowhere near a writing position. There is no pen or paper or writing surface. The image of the sack-holder, with narrow face and down-drooping moustachio, is entirely different from today’s effigy, with upturned moustache, goatee, pen and paper (see Figures 1 and 3). Further confirmation of its accuracy is the engraving made by Wenceslaus Hollar for Dugdale’s Antiquities. Hollar’s engraving shows the same image of a sack-holder (Dugdale 523).

Despite the insistence by Stratfordians that Dugdale and Hollar were mistaken, scholars of the two men all agree that both were very experienced and successful and that their work has proven to be reliable. Writing about Dugdale’s Antiquities of Warwickshire, his biographer was “filled with admiration at the general correctness of its details” (Hamper 483). Theodore D. Whitaker, a nineteenth-century antiquarian, noted Dugdale’s “scrupulous accuracy, united with stubborn integrity” (qtd. in Greenwood Problem 247–48 fn. 1). The original Dictionary of National Biography calls Dugdale “remarkable for general accuracy.” An illustrated history of Dugdale and Hollar by Marion Roberts in 2002 refers to Dugdale’s “careful observation of details of costume or armor” in his Warwickshire book (15).

Hollar too has a reputation for accuracy. Roberts says that “Hollar’s disciplined observation, his willingness to copy and his considerable skill at rendering detail to obtain accurately informative illustrations, suited Dugdale’s quest” (24). Hollar was “a master of precise and detailed renderings,” according to a book published by the Folger Shakespeare Library as an addition to an exhibition of his works (Doggett 9). For another exhibition of his works, the Smithsonian Institution described him as a “dispassionate reporter” with an “exacting eye and skillful hand” and a “prodigious talent for copy work, topography and mapmaking”. Supporting Hollar’s is his engraving of Dugdale himself. It shows Dugdale the writer at a desk with notebooks, books, paper, pens and ink. Commenting on this etching, Vladimir Denkstein notes in Hollar’s Works that “for all the care he took over the scholar’s features, Hollar seems to have been even more fascinated by the objects around him” (67). The only object that Hollar depicted with the effigy in his engraving of the Stratford monument is a sack.

The objection might be made that when Dugdale made his sketch in the Stratford church the light was bad or he was somehow distracted. Dugdale, however, was close enough and the light was good enough that he could transcribe the words of the epitaph under the effigy of the sack-holder. That there are mistakes in Dugdale’s voluminous work is not in question, but they turn out to be few and not material, or mis-transcriptions of town records by assistants. That he was incompetent and did not sketch what he was looking at in the Stratford church is argued by the independent scholar Diana Price, but her arguments do not hold up to scrutiny.[2] Dugdale’s sketch of the sack-holder stands as primary source evidence.

The first effigy: John Shakspere?

Richard Kennedy argues persuasively that Dugdale’s effigy was actually a portrait of John Shakspere, William’s father. According to Nicholas Rowe, John was known in Stratford as “a considerable dealer in wool” (Chambers 2:264). Thus the sack that the figure is holding is a woolsack, a symbol of John Shakspere’s trade. On his website, Kennedy cites a dozen authorities, including three from heraldry societies in England, who examined the Dugdale-Hollar effigy and confirmed that it’s a wool sack. In this scenario, at some point during the transformation from Shakspere Senior to Junior, someone would have added the plaque with William’s death date and an epitaph that was neither too lofty for a wool merchant nor too banal for a famous poet.

[pullquote]Another sign of Dugdale’s peculiar reticence is the title he gave to Hollar’s engraving in his book. It does not identify the monument as Shakespeare’s. It says simply: “In the North wall of the Chancell is this Monument fixt.”[/pullquote]

The abstruse eight-line epitaph itself also argues against the monument having been erected to a writer. As many non-Stratfordians have long observed, it says nothing about poems, plays or the theater. It opens with two lines in Latin referring to Nestor and Socrates, who were not writers; Virgil, who was much less important than Ovid for Shakespeare; and Olympus, which, for a writer, should have been Parnassus. The verse doubts the viewer can read (“read if thou canst”). The last two lines with the words “all he hath writt” have defied explication. Seemingly baffled by it, Stratfordian commentators omit the epitaph or decline to explain what it means. Chambers offers no explanation (2:182). Neither does Schoenbaum in his Documentary Life (254), while his chapter on “Shakespeare’s Epitaphs” in his Shakespeare’s Lives fails even to mention it (41–46). In short, the epitaph is an embarrassment for Stratfordians, which is why they usually ignore it.

In his book, Dugdale is suspiciously reticent about the Stratford man. He wrote more than three thousand words on the town of Stratford, but he notices the monument briefly only as an afterthought in the last sentence —

One thing more in reference to this ancient town is observable, that it gave birth and sepulture to our late famous poet Will. Shakespere, whose monument I have inserted in my discourse of the church. (523)

— a half-hearted, belated mention of the Stratford man as the great poet-dramatist. Another sign of Dugdale’s peculiar reticence is the title he gave to Hollar’s engraving in his book. It does not identify the monument as Shakespeare’s. It says simply: “In the North wall of the Chancell is this Monument fixt.” The only mention of “Shakspeare” in the illustration is in his transcript of the verse epitaph.[3] All in all, Dugdale appears less than enthusiastic that “our late famous poet” was from his home county.

One visitor to the Stratford church in 1634 who assumed that the monument was erected decades before to the London poet was a Lieutenant Hammond. In his travel diary, he wrote that in August or September he had seen “a neat Monument of the famous English poet, Mr. William Shakespeere; who was born heere” (Chambers 2:242–43). By that time, people had begun to believe that Shakspere was William Shakespeare, despite the contrary evidence of the sack-holder effigy.

Toward the end of the 1600s, the literary historian Gerard Langbaine was the first person to describe the sack of wool or grain as a cushion: “In the north wall of the chancel is a monument fixed which represents his true effigies [sic], leaning upon a cushion” (Langbaine 126). Since his wording is almost identical to that used by Dugdale for Hollar’s engraving in Antiquities, it’s clear he knew Dugdale’s book. Yet his description of the effigy as “leaning upon a cushion” suggests that there may already have been a change in the effigy of which Langbaine was aware, although there was as yet no drawing or engraving of it. Although the present effigy is not “leaning” upon a cushion, merely resting his hands on it, the image suggested by Langbaine’s phrasing in 1698 is too like the present image, and too unlike that of the Dugdale sack-holder, to ignore.

Dugdale/Hollar’s image of the sack-holder was repeated by Nicholas Rowe in his 1709 edition of the Shakespeare plays, for which he wrote the first attempt at a biography of the Stratford man as the poet-dramatist. Rowe had sent his friend, the popular actor Thomas Betterton, to Stratford “to gather up what remains he could of a name for which he had so great a veneration” (qtd. in Pope xvi). While looking into the records of the Stratford church, Betterton could not have failed to see the monument. Had the effigy been a writer as in today’s monument, not a sack-holder as by Dugdale/Hollar, Betterton, known for his “integrity, respectability and prudence” (DNB), would surely have alerted Rowe to the discrepancy. But Rowe not only used a copy of the dour, mustachioed, Hollar sack-holder for his 1709 edition, he used it again in his 1714 edition.

For more than half-a-century the Dugdale/Hollar image prevailed as the only published depiction of the effigy. If there were doubts or questions, none appear in the records. The engraving remained unchanged in the second edition (1730) of Dugdale’s Antiquities, which was “from a copy corrected by the Author himself,” according to the editor, William Thomas. Thomas, also a Warwickshire man, added that he himself had “visited all the churches” (Title page, ix). If during his visit to the Stratford church he had seen the effigy of a writer it seems unlikely that he would leave the image of a sack-holder unchanged in his edition of Dugdale. In fact, the sack-holder image would be used well into the twentieth century, despite the emergence of images resembling the writer in today’s monument. John Bell’s edition of Shakespeare in 1786 used a copy of Hollar’s engraving, and as recently as 1951 the Stratfordian professor Harden Craig used Hollar in his edition of the complete works as the only image of the poet-dramatist. Craig had this comment: “To what extent it was tampered with at a later time is not certain.” Nothing more. It’s obvious that Craig accepted that today’s monument is not the original.

A “monumental lapse”

The first depiction of a writer (not a sack-holder) in the Stratford monument was by George Vertue, an expert and prolific engraver. It was one of two illustrations of “Shakespeare” in Alexander Pope’s 1723–25 edition of the Shakespeare plays. In Vertue’s engraving of the monument, which includes the epitaph to “Shakespear,” the writer holds pen and paper on a thin cushion, just as in today’s monument (Figure 4). He wears an ear ring, the flat collar of a commoner, and his face is thought to bear some resemblance to the so-called “Chandos” portrait. More than likely, Vertue’s writer was the product of his imagination. There is nothing in his detailed diary showing that he or Pope had visited Stratford by that time. But for an edition of the Shakespeare plays, an illustration of the author’s effigy should show pen, paper and something to write upon, and so the lumpy sack tied at the corners in Dugdale and Hollar became Vertue’s thin cushion with decorative tassles at the corners.

More than likely, Pope had reasons of his own to want an illustration of a writer in the monument for his Shakespeare edition. He was a notorious Shakespeare idolater. He so idolized Shakespeare that he could not believe the dramatist actually wrote the bawdy passages in the plays. He blamed the actors. He went so far as to purge the play texts of the naughty bits and imperfect passages, banishing them to footnotes (Dobson 129–30). Later, he would take a leading role in arranging for the full-length statue in Westminster Abbey of the Bard leaning on some books on a pedestal.

As the decades passed, Vertue’s imaginary writer in Pope’s edition would become the prototype for illustrations of the Stratford monument. It would be widely copied, even for a “refurbishing” of the effigy itself in the Stratford church, and with a new face. It did not, however, completely displace the original Dugdale/Hollar effigy of a sack-holder, as mentioned earlier. The two very different effigies co-existed as the supposedly authentic images of the poet-dramatist.

Vertue’s engraving of a writer in the monument is one of two full-page illustrations of “Shakespeare” that he provided for Pope’s edition. The other is the frontispiece, and it is a portrait of a man under a banner proclaiming that he is William Shakespeare (Figure 5). His beard is neatly trimmed. He wears an ear ring, and around his neck is a large, stiff, white ruff more typical of a nobleman’s attire than a commoner’s. James Boaden, who wrote on the merits of many Shakespeare portraits, thought the portrait must be of King James: “Mr. Pope publish[ed] to the world a head of King James, and call[ed] it Shakespeare.” (131) Schoenbaum accepted it as an “elegant engraving by Vertue of King James surmounted by a laurel wreath and a scroll bearing the name William Shakespeare, to which Pope, in a monumental lapse, gave the place of honour as frontispiece to his edition of the dramatist” (Lives 212). Neither Boaden nor Schoenbaum explain why King James should be placed under a banner that identified him as William Shakespeare.

Fourteen years after Pope’s edition, Vertue did visit Stratford and the monument, but his sketch of it, which he drew later from memory, is again problematic. It shows a corner of the chancel, including the monument, the gravestone and part of the altar (Simpson 55–57). Although the effigy is not today’s, the general posture vaguely resembles it. It shows a balding man who might be seen as preparing to write, but instead of looking straight ahead, as in today’s monument, the figure turns to the left. A line might represent a quill pen, but it is out of place. Instead of a pillow (or a sack) there are some ambiguous lines. Instead of a moustache and goatee (or down-drooping moustache), the facial hair, if any, is a smudge. The facial features and expression are indiscernible, but even so it is clear that this is not the writer as Vertue depicted him for Pope. At the center of the sketch stands Edward Harley, second earl of Oxford (by the second creation) and Vertue’s patron, looking up at the monument. The two had stopped off at Stratford during their travels to see the monument.

Greene’s “Mimick Stone”

At the time of Vertue and Harley’s visit in 1737, Holy Trinity Church in Stratford had just acquired a new curate, Joseph Greene. Greene was not a shy and retiring parson. Besides curate, he was also schoolmaster, civic booster, theater buff, versifier, antiquarian, librarian for a wealthy neighbor, a great scribbler in the margins of books and an outspoken writer of letters. Shortly after his arrival he created a great stir in Stratford by eloping with the daughter of the town’s druggist and former mayor (Greene 3-13). He was also partial to an occasional “bottle of old Stingo.” Greene’s own writings indicate that it was he who directed the first (known) transformation of the Stratford monument in his church, changing it from a sack-holder to a writer. It was also Greene who found William Shakspere’s will, which he described as “dull and irregular” (59).

In 1746, an acting company performed Othello in Stratford as a benefit for the “repairing of the Original Monument of the Poet” (57). Moved by civic pride, Greene wrote a forty-five-line prologue for the performance, including these:

Hail, happy Stratford! Envied be thy name!

What City boasts, than thee, a greater fame?

Here, his first infant-lays great Shakespeare sung

Here, his last accents faultered on his tongue!

His Honours yet with future times shall grow,

Like Avon’s streams, enlarging as they flow!

Be these thy trophies, Bard, these might alone

Demand thy features on the Mimick* Stone,

The asterisk refers to a note that he is “alluding to the Design in hand” (59). He did not explain what design he had in hand nor whether it had anything to do with the features on the imitative effigy in stone to undergo “repair(s).” Later he would refer to “repairing and beautifying the monument” (168).

Greene also wrote the playbill for the performance, and his language is telling. The benefit, he wrote, was for “the curious original monument and bust (that)…is through length of years and other accidents become much impaired and decayed” (57, 164). This is the first complaint of decay, but it would not be the last. Over the years, such complaints would provide several similar opportunities for “renovations.”

Fund-raising began, but a dispute about the extent of work to be done seems to have delayed the project. Months passed. Finally, two years later, Greene writes of “repairing and re-beautifying” the monument, proposing that the painter John Hall do the work, provided “that the monument shall become as like as possible to what it was when first erected” (168–69). This is the first of four such avowals by Greene that the monument would not be changed or had not been changed.

Greene had the monument “repaired and re-beautified” early in 1749, and within months he was again protesting that he had not changed it. A fellow alumni of Oxford had questioned him about the stone used in the original. Greene replied: “I can assure you that the bust and cushion before it (on which as on a desk this our poet seems preparing to write) is one entire limestone ….” He then took care to add that

“as nearly as could be, not to add to or diminish what the work consisted of, and appeared to have been when first erected. And really except [for] changing the substance of the architraves from alabaster to marble, nothing has been changed, nothing altered, except the supplying with the original material (saved for that purpose) whatsoever was by accident broken off, reviving the old coloring and renewing the gilding that was lost.” (171, Greene’s emphasis)

The “chearful” Bard

A decade later, James West, an antiquarian friend and sometime patron, seems to have asked Greene about some irregularity of features, an “unnatural distance in the face” in the mask (mold) that he made. Greene responds that he made the mask with “Heath the carver” when they took the bust down and laid it on the floor. Defensively, Greene says the mask “answers exactly to our original bust” and is a “thorough resemblance” to the Droeshout engraving in the First Folio (77).

His testimony, however, is suspect. Dugdale/Hollar’s gloomy sack-holder in no way resembles the Droeshout. If Greene’s mask resembled the Droeshout it can only be because Greene made it so. Moreover, Greene’s recollections decades later of when he had the cast made are inconsistent. His repeated protestations over the years that he changed nothing ring hollow.

In June of the following year (1759), Greene placed a short article in The Gentleman’s Magazine, a popular periodical. He begins: “A Doubt, perhaps not unworthy of notice, has arisen among some whether the old monument Bust of Shakespeare in the Collegiate Church of Stratford upon Avon Warwickshire, had any resemblance of the Bard” (172–73). He notes such doubts did not arise until installation of the life-sized statue in Westminster (which Pope had helped to commission in 1741). Again there had appeared an image of Shakespeare different from any that had gone before, again raising the question: which was the real likeness?

Greene then draws a contrast with the Stratford bust. Its thoughtfulness, he says, “seems to arise from a chearfulness of thought.” The Bard retired “and liv’d chearfully amongst his friends.” His disposition was “chearful” (Greene’s emphases). At another point, he refers to him fondly and not a little possessively as “old Billy our Bard” (115). His cheerful Shakespeare can only have been the result of his repair and “re-beautification” of the gloomy visage that Dugdale saw and sketched for Hollar’s engraving.

The cheerfulness of the new effigy did not go unremarked. The eminent painter Thomas Gainsborough called it “a silly, smiling thing” and refused to paint it for David Garrick’s Jubilee in Stratford in 1769 (Deelman 68–69). In 1806, Stratford’s town historian R.B. Wheler said the effigy was indeed somewhat thoughtful “but then it seems to arise from a cheerfulness of thought” (his emphasis), and since the Bard’s disposition was cheerful the effigy properly depicts him (72–73). His book’s engraving, from his own drawing, shows an effigy that is neither gloomy like Dugdale’s nor vacant like today’s, but smiling a somewhat wan smile (70, 73). James Boaden, a London theater buff said the effigy showed the Bard “in his gayest mood,” an expression of “facetiousness … decidedly intended by the sculptor of the bust” (30–31, 34).

In 1814 the bust may again have been subjected to another round of “beautification.” John Britton, the prominent London antiquarian, had his agent take the effigy down for four or five days so that a cast could be made (14). “The face indicates cheerfulness, good humor, suavity, benignity, and intelligence,” he wrote two years later, going on to quote Washington Irving, who had said of the effigy, “I thought I could read in it a clear indication of that cheerful social disposition” (16). In 1825, Abraham Wivell, a London portrait painter, quoted with approval the aforementioned Wheler and Boaden on the effigy’s cheerfulness (10, 18). And later in the century, Matthew Arnold (1822–88) would begin his fourteen-line poem, “Shakespeare”:

Others abide our question. Thou art free.

We ask and ask: Thou smilest and art still,

Out-topping knowledge.

Twenty-eight years after he published his article, Greene again expressed some concern about representations of the effigy. In a letter to his brother, he said he would send him a small, slightly damaged painting on pasteboard that Hall had made of the monument. But first he noted at some length that it was “exceedingly difficult” to make an accurate painting of a carved bust, which “may perhaps in some measure account for the dissimilitude of a painted head as opposed to a carved bust of the same person” (145). It’s not clear why he would ruminate on the accuracy of the painting, but he certainly seems concerned. All in all, Greene protests far too much.

A painting resembling today’s monument, with a note on its back that said it was painted by Hall before he worked on the bust, came to the attention of Spielmann in 1910 (24), who argued that it proved the original monument held the effigy of a writer. Greenwood, however, noted some discrepancies that cast doubt on the authenticity of both the painting and the note. And, he added, “It seems much more probable that Hall should have painted it — if, indeed, he did paint it — after rather than before he had helped to ‘repair and beautify’ it” (Bust 33, Greenwood’s emphases).

Who did the sculpture work for Greene that refurbished the “much impaired and decayed” monument? Hall was a painter. No record says the town hired a sculptor. Not generally recognized is that letter of 1758 to his patron, wherein Greene mentions “Heath the carver.” Greene says Heath was with him and Hall when they took the effigy down from the wall. The Shakespeare Centre Library in Stratford has no information on Heath the carver (Bearman email). Nevertheless his name and his presence during the renovation is suggestive of the ability to “carve” a new effigy.

[pullquote]Joseph Greene had the motivation, the opportunity and the means to perpetrate the fraud and the cover-up.[/pullquote]The evidence strongly supports the view that Greene engineered changing the effigy from a gloomy sack-holder to a cheerful writer in the monument supposedly for the literary hero of Stratford. The visit of Harley and Vertue to Stratford shortly after Greene’s appointment as vicar may suggest a meeting of minds on the problem of the sack-holding effigy, and that, having obtained the tacit approval of the Stratford fathers, Greene, Heath and Hall silently created a more appropriate bust, following the figure as suggested by Vertue’s 1725 engraving (Figure 4).[4]

Joseph Greene had the motivation, the opportunity and the means to perpetrate the fraud and the cover-up, although in his own mind he probably felt he was doing it for the best of reasons: to show his hometown hero as he should be shown, as a writer.

The “stupid” Bard

The Dugdale/Hollar effigy was decidedly gloomy, and today’s effigy has never been called cheerful or smiling. Mouth agape, expressionless eyes staring into the middle distance, today’s bust has drawn harsh words even from Stratfordian scholars: Said Sidney Lee, “A clumsy piece of work … [with] a mechanical and unintellectual expression,” (522). “Curious and at first sight stupid,” said M.H. Spielmann, even as he tried valiantly to defend it as authentic (9). It has “a general air of stupid and self-complacent prosperity,” said J. Dover Wilson, who concluded that the task was “quite beyond the workman’s scope” (5–6).

Sixty-five years after Greene’s “refurbishing,” at a time when Bardolatry was reaching high tide, another sculptor had an opportunity to work on the effigy. He was George Bullock, who “began his career as a sculptor” and later went into the business of making furniture (Thornton 6). In 1814, the prolific London antiquarian and writer John Britton commissioned Bullock to make a mold of the Stratford effigy so plaster casts could be made (5–6). One of these plaster casts can be found in Sir John Soane’s Museum in London. On the back is inscribed, “Moulded by Geo: Bullock from the origenal [sic] in the church at Stratford, Decr. 1814” (Thornton 96). The plaster cast in the Soane Museum shows no sign of decay. In fact it looks very much like today’s effigy. It is not cheerful or smiling, raising questions of how Bullock was able to make such a durable plaster cast from a “decayed” effigy and what could have happened to the cheerful smile.

Answers may be found in a close reading of Britton’s account of what happened when Bullock took a mold of the bust. Although the evidence is only suggestive, it seems likely that it was George Bullock and the Stratford civic leaders who are responsible for the effigy as it is seen in the church today. Britton supplies the evidence in his 1849 book (6–7, 12) in which he dismisses various paintings of “Shakespeare” and defends the Stratford bust as having “all the force of truth … a family record … raised by the affection and esteem of his relatives … [and] consecrated by time” (12). Thirty-three years later he would repeat his “firm conviction that the Stratford Effigy was the most authentic and genuine Portrait of the Bard” (6). He then described how the Stratford civic leaders were involved and how long it took to take a mold of the bust:

Mr. Bullock’s visit to Stratford [in December 1814] was made under the most favourable auspices. Through the influence of my old friend, Mr. Robt. Bell Wheeler, the historian of Stratford, (a most devoted Shaksperian,) Mr. Bullock readily obtained permission from the Vicar, (the Rev. Dr. Davenport,) and the parochial authorities, to take a mould of the Bust; and many and interesting were the comments of the Artist on that precious memento of the Immortal Bard. He was much alarmed on taking down the “Effigy” to find it to be in a decayed and dangerous state, and declared that it would be risking its destruction to remove it again.” (6)

He then quotes from Bullock’s December 1814 letter wherein Bullock indicates that he may have done more than just make a mold of the effigy. It reads in part:

I had every preparation made and assisted in erecting a sort of scaffolding before I was aware of the difficult task I was going to perform. In short, instead of one day’s work, I have found four or five, as I mean to mould the whole figure. (6)

Four or five days seems excessive just to take a mold of the bust, nor is it credible that Bullock would take a mold of a decayed and crumbling bust without repairing it. It’s more likely that after the effigy was removed from its niche, Bullock silently repaired the decaying monument, altered its appearance and then took a mold of it. Although these reports by Britton and Bullock cannot be taken to prove that Bullock and the Stratford civic leaders were involved in changing Gainsborough’s “silly smiling thing” to today’s stolid, staring figure, the evidence for such a change fits well with the fate of the Stratford bust over the centuries. Adding to this probability is the fact that, two decades later, in his long, detailed description of his 1836–37 renovations to the chancel, Britton had nothing to say about what was done to the bust.

Like their predecessors in Greene’s time, Britton the proactive Bardolator, Bullock the sculptor, Wheler the town historian, the Vicar of Holy Trinity Church and the other “parochial authorities” of Stratford had the motivation to make sure the effigy looked like a writer — namely, Shakespeare’s increasing status as a national hero and the civic pride and commercial ambitions of the local business community.

Bullock’s mold spawned several different casts. Abraham Wivell said that one entrepreneur made three new molds from one of Bullock’s casts, a cast of the entire effigy, one “without the hands” and one of the head only. He said that Wheler of Stratford had one of the head and shoulders and that Britton had a sculptor make a half-size head and shoulders bust, then had a mold made of that. Bullock’s mold, he said, was afterwards destroyed, and the casts soon became scarce” (17–18 fn.).

Two decades later, the Shakespearean Club of Stratford wanted to renovate and restore the monument and the chancel. According to Charlotte Stopes, who examined records in Stratford, the club noted that it had “long beheld with regret, the disfigurement of the Bust and Monument of Shakespeare, and the neglected condition of the interior of the Chancel which contains that monument and his grave” (121). The club resolved to raise funds “for the Renovation and Restoration of Shakespeare’s Monument and Bust, and of the chancel.” The King and the town each contributed fifty pounds. Britton, who led the fund-raising in London, was determined to renovate the whole chancel, particularly the roof, and he hired an architect to make drawings. It’s possible that work was also done, as the club intended, to renovate and restore the reportedly now disfigured bust that Bullock had worked on twenty years earlier. If so, Britton makes no mention of it in his detailed description of the work on the entire chancel in 1836–37 (28–32). Stopes refers to seemingly extensive records in Stratford (118, 120, 122).[5]

In 1973, thieves reportedly looking for manuscripts in the monument removed and damaged the three-hundred-pound bust. Levi Fox, director of the Shakespeare Birthplace Trust, is quoted as referring to a “restoration,” but records, if any, about how much restoration and repair work was done have not been made public (Ogburn 796–97). Shortly after this, Schoenbaum examined the effigy and said only that it had been slightly damaged (Life 256 fn. 2). In 1996, John Michell wrote that “modern experts have closely examined the bust which is made of one block of stone, and find no evidence that it has ever been substantially repaired” (97).

Today the effigy appears to be in good shape. It’s very unlikely that the unblemished bust we see today is, as Stratfordians wish to believe, the one erected almost four centuries ago. The effigy of today must date to more recent times, probably to Bullock’s work in 1814, and perhaps again in 1836–37, when more modern materials were available.

A review of all the evidence indicates that the Stratfordians have a major problem. To uphold their faith in William Shakspere of Stratford as the great poet-dramatist, they must either dismiss the Dugdale/Hollar effigy, even though it meets the requirements for solid, primary-source evidence, or cloud the issue with spurious debates over “authenticity.”

The cumulative power of the evidence is persuasive. Dugdale’s eyewitness sketch of the sack-holder in the original monument, Hollar’s engraving of it through two editions of Dugdale’s book, Rowe’s copy of it almost a century later for his Shakespeare edition, Vertue’s “Shakespeare” as a nobleman in a ruff, then as an imaginary writer for Pope’s edition, Greene’s “cheerful” renovation — all lead to the conclusion that today’s monument is not the original and that it is, instead, a monumental fraud. The Dugdale/Hollar images of a sack-holder, the evidence that the monument was changed more than once over the centuries, and Richard Kennedy’s convincing argument that the original bust depicted, not William Shakspere, but his father John Shakspere, the wool-dealer, add to the growing mountain of evidence that the great poet dramatist William Shakespeare was someone other than William of Stratford.

Richard F. Whalen is the author of Shakespeare: Who Was He? The Oxford Challenge to the Bard of Avon (Greenwood/Praeger 1994). He is a past president of the Shakespeare Oxford Society and has written numerous articles for Oxfordian publications. He is co-general editor of the Oxfordian Shakespeare Series of the most popular plays, with introductions, commentaries, and notes reflecting authorship by Edward de Vere (Earl of Oxford). This article expands on a paper delivered at the eighth annual Edward de Vere Studies Conference, April 15–18, 2004, at Concordia University in Portland, Oregon. He thanks Barbara Burris, Ramon Jiménez, Eddi Jolly, and David Roper for their assistance.

Endnotes

[1]. Schoenbaum overlooked the fact that Stopes, Greenwood and Lee had seen the sketch and reported on it, although it had not yet been published. E.K. Chambers also mentioned its survival (2:184). More recently, Gerald Downs of Redondo Beach, California, took the first photograph of it (Fig. 1).

[2]. Price was the first to publish Dugdale’s sketch (156). An anti-Stratfordian, she nevertheless maintained in The Review of English Studies (May 1997) and then in her otherwise fine book, Shakespeare’s Unorthodox Biography, that Dugdale and Hollar were inaccurate. In the journal article she said, “Dugdale’s image generally corresponds to Shakespeare’s monument [of today], yet most of the details are inaccurate or misleading.” In her book she continues to make the same argument: “Overall his sketch corresponds to [today’s] bust” despite details that are “missing or wrong.” However, a completely different face, arm position, woolsack vs. pillow and presence or absence of pen and paper can hardly be considered “details.” Eddi Jolly, writing in the De Vere Society Newsletter, follows Price closely. Although she grants that the Dugdale/Hollar sack seems exactly like the sack in the crest of the Woolmen’s Guild, she then cites cushions in other monuments, even one with a man reading a book. A reader, however, is not a writer; and a sack is still a sack.

[3]. Dugdale’s sketch as seen today also has a title on it, but he did not put it there; it was added later. It follows closely the title of the monument in his book: “In the North wall of the Chancell is this Monument fixt.” Modernized and expanded it became: “In the north wall of the Quire is this monument fixed for William Shakespeare the famous poet.” The ink is much darker and thicker than in the sketch, the handwriting is modern and the spelling of all the words is today’s spelling, including “Shakespeare.”

[4]. Greene also had two other precedents: Thomas Hanmer’s recent edition of Shakespeare (1744), with Gravelot’s engraving, modeled on Vertue’s engraving of the writer in Pope’s edition (Fig. 4), and the very popular editions of Shakespeare (1733 and 1740) by Lewis Theobald, which Greene twice expressed interest in buying (56). Theobald described the effigy as having “a cushion spread before him, with a pen in his right hand, and his left resting on a scroll of paper” (13). No evidence puts Theobald — or Hanmer — in Stratford. Theobald certainly would have seen Vertue’s engravings, for he was Pope’s most outspoken critic.

[5]. In his online article, David Roper maintains that Greene did not raise enough money to change the sack-holder effigy to that of a writer and that the sack-holder was in the monument until 1835, when funds were raised to repair it. One would think, however, that by the late 1700s–early 1800s, with Bardolatry rampant, that it would have been noted that the effigy was inappropriate. Not only did Edmund Malone see the effigy on his visit in 1793, he brought it “back to its original state by painting it a good stone-colour.” (Chambers 2:184). If at that time the effigy had still been the sack-holder and not Greene’s “cheerful” writer, surely Malone or someone else would have said something.

Works Cited

Bearman, Robert. “Heath the Carver.” Email to author, May 2004.

Boaden, James. An Inquiry into the Authenticity … Portraits of Shakspere. London: Triphook, 1824.

Britton, John. Essays on the Merits … Shakspere … his Monument. London: 1849.

Chambers, E.K. William Shakespeare: A Study of Facts and Problems. 2 vols. Oxford: Clarendon, 1930.

Craig, Harden. Ed. The Complete Works of Shakespeare. Chicago: Scott, Foresman, 1951.

Dobson, Michael. The Making of the National Poet. Oxford: Clarendon Press, 1992.

Doggett, Rachel, Julie L. Biggs and Carol Brobeck. Impressions of Wenceslaus Hollar. Washington DC: Folger, 1966.

Deelman, Christian. The Great Shakespeare Jubilee. New York: Viking, 1964.

Denkstein, Vladimir. Hollar Drawings. New York, Abaris, 1977.

Dugdale, William. The Antiquities of Warwickshire, Illustrated. 1656. London: Thomas Warren, 1656. 2nd ed. “printed from a copy corrected by the author himself and with original copper plates.” Ed. William Thomas. London: Osborn and Longman, 1730.

Greene, Rev. Joseph. Correspondence. Ed. Levi Fox. London: HMSO, 1965.

Greenwood, G. George. The Shakespeare Problem Restated. London: John Lane/Bodley, 1908.

__________. Is There a Shakespeare Problem? London: Lane, 1916.

__________. The Stratford Bust and the Droeshout Engraving. London: Cecil Palmer, 1925.

Hamper, William, ed. The Life, Diary and Correspondence of Sir William Dugdale. London: Harding, 1827.

Hanmer, Thomas. The Works of Shakespear. Oxford: At the Theater, 1744.

Honan, Park. Shakespeare: A Life. Oxford: OUP, 1998.

Jaggard, William. Shakespeare Bibliography. Stratford-on-Avon, 1911.

Jolly, Eddi. “Images of ‘Old Billy Our Bard.’” De Vere Society Newsletter. April 2002: 2–12.

Kennedy, Richard. The Woolpack Man. http://webpages.charter.net/stairway/WOOLPACKMAN.htm

Langbaine, Gerard. The Lives and Characters of the English dramatick poets. London: Leigh, 1698.

Lee, Sidney. A Life of William Shakespeare. 1898. New York: Macmillan, 1924.

Michell, John. Who Wrote Shakespeare? London: Thames and Hudson, 1996.

Ogburn, Charlton. The Mysterious William Shakespeare. McLean VA: EPM, 1984.

Piper, David, ed. “O Sweet Mr. Shakespeare I’ll Have His Picture.” The Changing Image of Shakespeare’s Person: 1600–1800. London: NPG, 1964.

Pope, Alexander. The Works of Shakespear. London: Tonson, 1723–25.

Price, Diana. Shakespeare’s Unorthodox Biography. Westport CT: Greenwood, 2001.

Roberts, Marion. Dugdale and Hollar: History Illustrated. Newark NJ: Delaware UP, 2002.

Roper, David. “The Truth Behind Shakespeare’s Monument at Stratford-upon-Avon.” 1994 (https://www.big-lies.org/de-vere-shakespeare/edward-de-vere-david-roper.html).

Schoenbaum, Samuel. William Shakespeare: A Documentary Life. New York: OUP, 1975.

__________. William Shakespeare: A Compact Documentary Life. New York: OUP, 1977.

__________. Shakespeare’s Lives. Oxford: Clarendon, 1991.

Simpson, Frank. “New Place: The Only Representation of Shakespeare’s House, from an Unpublished Manuscript.” Ed. Allardyce Nicoll. Shakespeare Survey 5. Cambridge: CUP, 1952.

Spielmann, Marion H. The Title Page of the First Folio of Shakespeare’s Plays: A Comparative Study of the Droeshout Portrait and the Stratford Monument. London: Oxford UP, 1924.

Stopes, Charlotte C. “The True Story of the Stratford Bust.” Shakespeare’s Environment. 1904. London: Bell, 1914.

Theobald, Lewis. The Works of Shakespeare. London: Bettesworth, 1733.

Thornton, Peter, and Helen Dorey. A Miscellany of Objects from Sir John Soane’s Museum. London: Laurence King, 1992.

Vertue, George. Note Books. Vols. 18, 20, 22, 24, 26, 30. Oxford: Walpole Society, 1930.

Wheler, Robert Bell. History and Antiquities of Stratford-Upon-Avon. Stratford-upon-Avon: Ward, 1806.

Wilson, J. Dover. The Essential Shakespeare. Cambridge: CUP, 1935.

Wivell, Abraham. An Historical Account of the Monumental Bust of William Shakspeare. London: By the author, 1827.

Wood, Michael. Shakespeare. New York: Basic Books, 2003.