Originally published in THE OXFORDIAN, Volume 2, 1999, pages 60-75

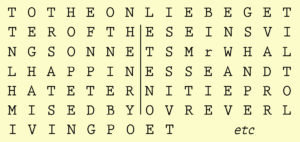

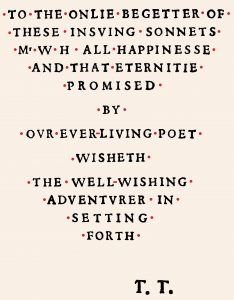

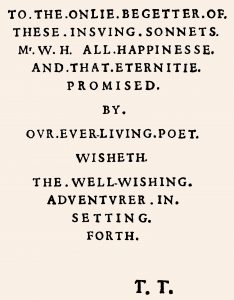

Here it is, so familiar, and so obscure: what an amazing production! There’s nothing remotely like it anywhere else in Elizabethan or Jacobean literature. What does it mean, for a start? What is it trying to tell us? The opening phrase is so well-known, “To the onlie begetter,” but how many people know that the spelling of “onlie” is very rare indeed? It could have been, in its tiny way, a clue to something quite unsuspected until very recently. Surely there is rather more in the Dedication than first meets the eye.

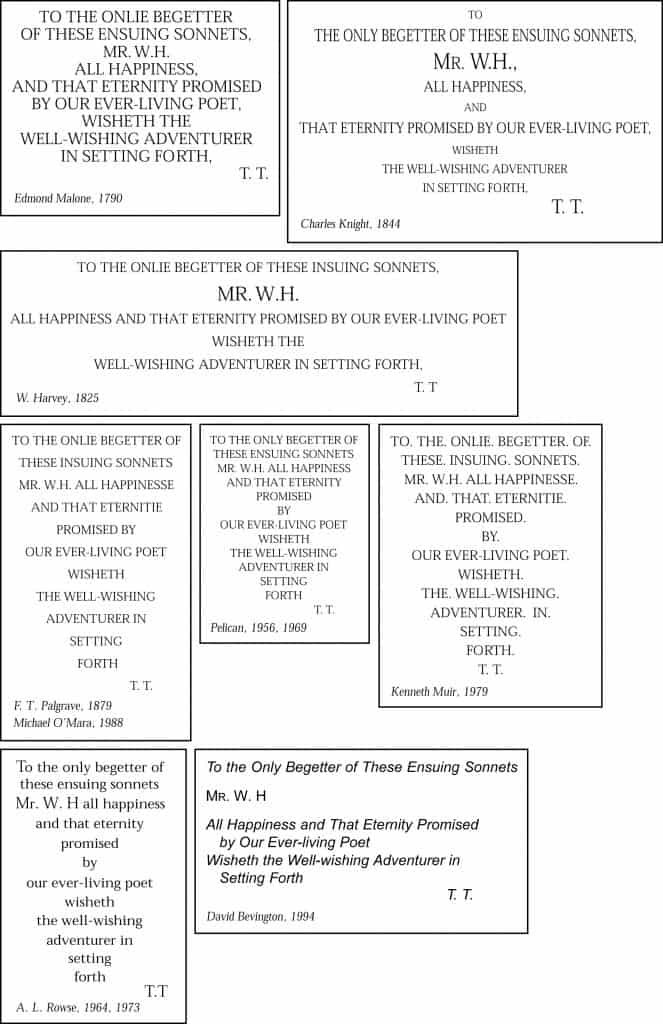

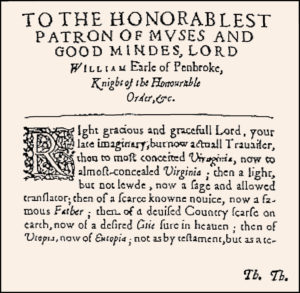

Just to show you how peculiar it is, here is a look at one of Thorpe’s other dedications, (below). You can see that it has a heading, the text is in lower-case italics, some words have capitals, and several words are in Roman type for emphasis. This is absolutely typical of most dedications of the period, often with the Roman and italic fonts interchanged. Now compare it with the Sonnets’ Dedication. They couldn’t be more different!

I first became aware of it in 1964, the 400th anniversary of the birth of a certain gentleman from Stratford. It was therefore seized upon as a milestone in Shakespearean studies, and it did not go unnoticed by the publishing fraternity. According to the London Sunday Times, his birthday was “the peak of the biggest literary bonanza in history.” Over 400 books dealing with Shakespeare were published to commemorate the event, and among them, none was more eagerly awaited than one with the title “Mr. W. H.,” by the great Shakespeare scholar Leslie Hotson, who claimed to have finally determined, once and for all, the identity of the mystery person to whom the Sonnets were dedicated. Such was the hype surrounding this book that I found myself buying a copy as soon as it was published. I still recall the excitement I felt when I took the book home and devoured it eagerly. Here was the solution to the biggest literary mystery of all time! (Bar one, I would now add.)

I found it completely convincing. It is a marvellous book, full of wonderful things, and I strongly recommend it to anyone interested in Shakespeare, or in the mechanics of self-deception––for its main thesis is completely wrong. But at the time I didn’t know that.

Hotson, I don’t need to remind you, had a tremendous reputation. At the age of twenty-six or so he had discovered in the Public Record Office the report of the inquest on Christopher Marlowe, whose death up till then had been shrouded in mystery. (The fact that it has subsequently been shrouded in still more mystery is another story.) This coup started him on a golden trail of further discoveries, this time about Shakespeare, of injunctions naming him, and details of his friends––not always very desirable characters, it must be said––and in 1949 he hinted for the first time that he had discovered who “Mr. W. H.” was. With such a track record, whatever he said was listened to very seriously. He delved away for the next fifteen years or so, and by 1964 (pure coincidence of course), all could be revealed.

It was a marvellous discovery. Practically every Elizabethan of suitable age, with initials W.H. or H.W., had already been put forward as the young man, but Hotson managed to find a new one. This was a certain William Hatcliffe, admitted to Gray’s Inn as a law pupil in 1586 and the next year elected Prince of Purpoole, the title given to the student who had been chosen to act as a kind of temporary Lord of Misrule, or Lord of Liberty, to preside over the festivities of the Christmas season.

This position, Hotson explains, was one of enormous prestige and dignity. In effect, the “Prince” was expected to act like a Prince of royal blood, and, for the brief period of his reign, would be accorded all the respect and deference such a Prince would command. Both for him and for the other students it was a kind of practice run for life at the Court of Queen Elizabeth, since many of the students were of good family, and might well find themselves in exalted circles in later life. And indeed, his installation ceremony was magnificent, modeled on that of a Coronation, with a procession of over 200 students and others taking part, each with a defined role to play, shadowing the various Officers of State and other dignitaries.

Why, then, was Hotson’s theory so appealing? For a start, it explained simultaneously both the “Mr.” of Mr. W. H., and all the references in the Sonnets to the high status of “the Fair Youth.” In various sonnets he is addressed as “Lord,” “prince,” “sovereign,” “king,” while elsewhere he is referred to obliquely as “the Sun,” “a God,” “the Ocean,” all––as Hotson shows––terms applied to royalty. Many scholars thought that the youth must be a lord, such as Henry Wriothesley, Third Earl of Southampton, or William Herbert, Third Earl of Pembroke. But Hotson argued like this: had he been a real Lord, he could hardly be addressed in the Dedication as “Mr.” but if he was a “Mr.,” he could have been a temporary Prince. Then there was Hotson’s masterstroke, which comes from “Sonnet 125,” which starts:

Were it ought to me I bore the canopy,

With my extern the outward honoring.

Hotson shows by numerous quotations from contemporary documents that a “canopy” could only, by law, be carried over the Sovereign. Hence, if the canopy in the sonnet is a real canopy, carried on poles by four distinguished people at a public ceremony, then the sonnet must either be addressed to the Sovereign, or to someone elected to a temporary position where they are treated like one––in other words, someone like Hatcliffe, Prince of Purpoole.

I was completely captivated by Hotson’s theory. It seemed to solve so many of the problems associated with the Sonnets, such as the affection between the poet and the young man, and their sharing the same mistress––hard to understand as between commoner and Earl, but readily believable as between poet and law student, so much closer in station. I read the book two or three times over the next few years, still with great enjoyment––and I do seriously recommend it––but with gradually increasing disbelief, until eventually I realized that of genuine evidence connecting Shakespeare with Hatcliffe there was nothing at all. In particular, Hotson’s evidence about the canopy was self-defeating, since elsewhere in the book he quotes a long passage from an account (the Gesta Grayorum) of the procession which took place a few years later, and this makes it quite clear that no canopy was carried over the Prince of Purpoole. Through some unaccountable oversight, Hotson failed to point this out.

Only one piece of evidence remained which appeared to connect Hatcliffe with Shakespeare, and that was in the Dedication, which Hotson boldly declared was a cryptogram. It is indeed a very odd and strange production, completely different from Thorpe’s other dedications. The Blount dedication (above) shows Thorpe’s efforts to be witty and entertaining, at least by Elizabethan standards, and actually it is quite funny. “Blount, I purpose to be blunt with you,” and so on, while the dedication to Pembroke (right) is full of sophisticated word-play of the most excruciating kind, witty and tedious, totally different from the Dedication to the Sonnets. “Most-conceited” is contrasted with “almost-concealed”; Viraginia with Virginia––very skillful word play; Utopia versus Eutopia––there’s a subtle difference which I had to look up. Both these dedications are so different from the Sonnets’ Dedication, that it is hard to believe that all were written by the same person.

Now let’s return to Hotson’s claim that the Dedication was a cryptogram. He gave a number of reasons for this idea, such as the layout, the capital letters, the full-stops, but his chief reason is that the sentence is back-to-front. What we would expect is:

To the only begetter of these insuing sonnets, Mr. W. H., the well-wishing adventurer T. T.

(in setting forth) wisheth all happiness, and that eternity promised by our ever-living poet.

In other words, what we expect is: “To Mr. W. H., the publisher T. T. wishes all happiness” and so on. Hotson gives examples of nine similar dedications, all of which have this sort of word order, that is, “To Sir A. B., X. Y. wishes happiness.” But the Sonnets’ Dedication has the order “To Mr. W. H., happiness wishes the publisher.” Hotson states that it is unique, and that he has never seen another dedication like it. In fact, he calls it “preposterous,” a good word, I think. (It is the more extraordinary, in that it could so easily have been amended to read “To Mr. W. H., happiness is wished by the publisher T. T.” It would then have seemed perfectly normal, at least in this respect.) Peculiar wording, Hotson goes on to say, is often a pointer to some cryptic intention, and he proceeds to solve the cryptogram as follows:

He starts with “Mr. W. H.” in line 3, moves down to pick up the H in the next line, chooses HAT from this word, then drops down to line 7, and picks up LIV from EVER-LIVING. In this way he obtains HATLIV, a reasonably good shot at “Hatcliffe” (or so he tells us). I accepted this unthinkingly to begin with, but on the third or fourth reading of the book, in about 1967, I happened to reach this passage late at night, around 11 o’clock, and it suddenly became clear to me that it was nonsense––utter nonsense. There are too many arbitrary steps; one could find several different names made up from a syllable near the beginning and a syllable towards the end. Cryptography is systematic and scientific, and picking out syllables at random is not the way to solve a genuine cipher; there must be some kind of regular pattern (or algorithm). It is this pattern which gives the solver reason to think that he has found the right solution. Hotson’s solution has nothing even approaching a regular pattern––it is all far too flimsy! In any case, it is obvious that Hotson was very strongly biased towards the result he claimed to find. It is not a good idea to have preconceptions in this kind of endeavor.

If the piece was a cryptogram (as Hotson had argued so strongly), then it was clear to me that it must be concealing something else. As it was so late, I decided to give myself five minutes to find the solution, and if it didn’t work out, I would forget the whole thing.

One of the oddest features of the Dedication is the full-stops after every word. Puzzling over this, at about 11.01, it suddenly occurred to me that they suggest counting words. One can imagine someone with a pen or pencil touching the point on the paper after each word as it is counted. The stops and hyphens tell one to count the two compound words separately, it would seem, and that “Mr. W. H.” counts as three items, not one. If we have to count words, the obvious thing to do is to see whether every 3rd word, or 4th or 5th and so on, yields a message. It takes very little time to do this, and the result in every case is rubbish. For example, every 5th word gives this message: OF. W. THAT. EVER. WELL. FORTH., not very promising. It was now about 11.02.

The next simplest thing to do, still sticking with counting words, is to alternate two numbers, and for example to take the 3rd word, followed by the 5th, and then the 3rd, and so on. But if the scheme is like this, trial and error would get us nowhere, as there are so many possible combinations of two small numbers. Indeed, if we try and guess two numbers, we might well end up with two or more possible messages, and be unable to decide between them. If the cryptographer was working along these lines, it would be obvious to him (just as it is obvious to us) that he must tell us what the two numbers are, either directly, or hidden in some simple fashion. It is now 11.03.

There are no numbers in the Dedication, and nothing to suggest two numbers. But if we have to count words, there must be numbers somewhere. Time was running out. I was about to give up. 11.04. Then I suddenly focused in on another peculiarity. The text is laid out in three blocks, which might suggest three numbers. The number of lines in each block is something that the cryptographer would have had under his control. The lines in the three blocks give us the three numbers: 6-2-4. Perhaps this is the clue to the hidden information? Remember, I was after “Mr. W. H.” Counting through, using these numbers as the key, I found the following:

THESE. SONNETS. ALL. BY. EVER. . . .

This message started off in quite an interesting fashion, but sadly it ended up as rubbish, just as the other attempts at a solution had. I had never heard of any Elizabethan poet called EVER, and it sounded very unlikely as a name anyway. Obviously the Dedication was not a cryptogram, after all, so I put the book down, feeling a little disappointed, and went off to sleep. In any case, like Hotson, I was looking for a clue to the identity of “Mr. W. H.,” and had never doubted that the gentleman from Stratford was the author of the Sonnets and everything else. Incidentally, I would like to suggest that perhaps Hotson’s heart was really in the right place, all along, since after analyzing many of the sonnets, he says finally, “If one had to put the Sonnets into one word, that word would be Truth.”

I forgot all about this discovery, or rather non-discovery, for the next two or three years, until having time to spare in a big library I decided (on an impulse) to look at the article on Shakespeare in the Encyclopedia Britannica. I leafed idly through it until towards the end, when I found a section headed “Questions of Authorship.” I was rather surprised to find anything on such a fringe topic (my apologies all round), but duly read the general argument and a paragraph on Francis Bacon, until I was amazed to come upon the following two sentences.

A theory that the author of the plays was Edward de Vere, 17th earl of Oxford, receives some circumstantial support from the coincidence that Oxford’s known poems apparently ceased just before Shakespeare’s works began to appear. It is argued that Oxford assumed a pseudonym in order to protect his family from the social stigma then attached to the stage, and also because extravagance had brought him into disrepute at Court.

I immediately recalled the rubbish message of a few years back, since obviously EVER could now be read as E. VER or Edward Vere. A strange coincidence, not to say a thought-provoking one. But I still remained very skeptical, and was sure that chance was the most likely explanation of this odd result.

Books on Edward deVere were not easy to find in those days, but I did read the book by Hilda Amphlett, and found it very far from convincing. It seemed to me that the coincidences between Oxford’s life and the plots of Hamlet, or All’s Well, or the Gad’s Hill episode, could all be explained if Shakespeare spent some time in Oxford’s house-hold, or had a friend who had. I emerged from the book an even stronger Stratfordian than before. I did however make a mental note to look into the authorship question when I had more time, partly I think because I had noticed something which Hilda Amphlett doesn’t mention––a strong resemblance between the portrait of the young deVere and the Droeshout engraving in the First Folio. Another odd coincidence.

We now skip some fifteen years, and in the fullness of time, Charlton Ogburn’s book was duly published in the UK. I read it with much the same excitement as I’d experienced reading Hotson’s book twenty-odd years earlier. But despite the fact that I had the (dubious) solution to the Dedication cipher at the back of my mind while reading it, again I was left unconvinced. Stratford still held the day.

Although Shakespeare seemed to have left very few signs of his impact on the theatrical world, it seemed far more extraordinary that Oxford had left so few. A commoner could work in the theatre unobserved, but surely not a great lord? Seventy years after he had been first put forward, surely more evidence should have come to light? Why the complete silence by his contemporaries? Why continue the cover-up twenty years after his death, when the First Folio was published? And the specialized knowledge that the plays exhibited was just the sort of knowledge that a clever lad, up from the sticks, might pick up from his aristocratic patrons, or from casual acquaintances in taverns.

True to form, I re-read Ogburn’s book again two or three times, and I won’t bore you with what it was which made me change my mind, but it finally dawned on me that it was important to try to see whether the message in the Dedication might actually be genuine, and not just an accident of chance. With this in mind, I read numerous books on codes and ciphers, and attempted to find out what was known about Elizabethan cryptography.

I discovered that this type of cryptogram is called an innocent letter code, since the objective is to distribute the words of the secret message systematically throughout the words of what seems like a normal letter. It is a method often used by people locked up, wanting to communicate secretly with friends in the outside world. It was frequently used to good effect by prisoners of war in World War II, notably those in Colditz Castle sending information about the German war effort back to the UK.

In order to indicate the key to the hidden message, various schemes can be used. For example, the 10 letters in “Dear George” could indicate every 10th word, and the 12 in “My Dear George” every 12th word; or the date “September 5th” could indicate the key 9-5, that is, take the 9th and 5th words alternately throughout the letter, September being the 9th month. These tricks are all described in books on elementary codes and ciphers, such as are published quite often nowadays. So the idea of hiding the key in the text is a commonplace today, and would certainly have been as obvious to the Elizabethans as it is to us.

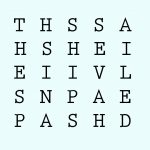

But what I was really hoping to find was examples of Elizabethan ciphers. This took quite a long time, basically because there aren’t any. None have survived, although several people at the time did describe various useful techniques which might have been used, for all we know. (Strictly speaking, one should class acrostics as very simple ciphers. The Elizabethans were certainly fond of them, and quite a lot do survive, especially in poetry.) The only example of a cipher I was able to find was in a biography of John Dee, the Elizabethan savant and astrologer (he was instructed by Robert Dudley to choose an auspicious day for the Queen’s Coronation, and many people would agree that he did a good job). Here (left) is the example his biographer gave to illustrate a method described by John Dee. This reads, going down and up the columns, “The Spanish ships have sailed.” The message would be sent off, reading across, as T H S S A H S H E I. . . . To someone intercepting it, it would obviously proclaim itself as a coded message and to decode it, all one has to do is to count the number of letters––25––and write it out again in a 5 by 5 square. It is amusing to learn that Dee regarded this as “a childish cryptogram such as eny man of knowledge shud be able to resolve.”

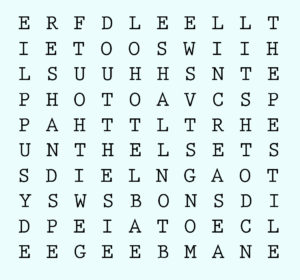

Another similar example (right) is given by Bishop John Wilkins, in a book published in 1641, with the splendid title, Mercury, or the Secret and Swift Messenger, which described all the cryptographic methods he knew of which he thought might be useful in the Civil War. Here one has to start reading from the top right-hand corner, “The pestilenc[e] doth still increase . . .,” etc. Again it would be sent off in the form: E R F D L E E L L T . . . , and so on. Incidentally, it is interesting to see that in order to get the message into a perfect 10 by 10 square, the word pestilence is spelt without the final e. Clearly what one has to do when receiving this kind of cipher, nowadays called a transposition cipher, is to set out the letters of the code into an array, either a square or a rectangle.

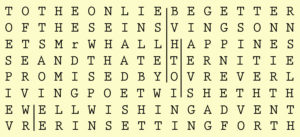

Now I can’t recall what made me think of doing this to the Dedication, but I do remember that I put it off for months, because I thought that it would take hours, if not days, of hard work––and also because I thought the chance of finding anything was vanishingly small. Eventually I got down to it, and started by counting the number of letters––144, which rang a very loud bell, as it is 12 squared, and has many other factors.

I then wrote the Dedication out into arrays, starting with a square having 12 rows of 12 letters, then rectangles with rows of 15 letters, 18, 21, 24, and so on. Thankfully, one doesn’t have to write out all possible arrays, as words can be read out diagonally as well as up and down. For example, from the 12 by 12 array, one can inspect arrays with 11 letters and 13 letters in each row by reading diagonally, while the array with 15 letters in each row also allows one to inspect the arrays having 14 and 16 letters per row, and so on. So far from taking days, this took about 20 minutes, which was a relief.

The first thing I noticed was in the array with 15 letters in each row (right): HENRY! It is evident that the letters of the name are all equally spaced––every 15th letter starting from the H spells out the name. This is sufficiently unusual to suggest that it might have been deliberately arranged by a cryptographer. But Henry who? For some weeks I thought it might possibly be the name of the man who had (perhaps) hidden the message about EVER in the Dedication, though it didn’t seem to me that he deserved to immortalize himself in this way. Perhaps his name was “Henry Oliver,” the surname being indicated by the letters OLVR which follow on down from HENRY, and I did look in various books to see if such a person flourished at the time, without success.

Eventually the penny dropped. In the array with 18 letters in each row (right) I had repeatedly overlooked something. There, split up into three bits, is the name WR-IOTH-ESLEY, spelt perfectly, just as it was always spelt officially. I first noticed the letters ESLEY in the middle column, and almost immediately the letters IOTH in the one next to it. At that moment I knew with absolute certainty that I would find the letters WR somewhere, and there they are, at the bottom of the second column. Moreover this is a perfect rectangle, where the cryptographer would naturally try to hide the most important information, since perfect rectangles are where a cryptanalyst would look first of all for something hidden. And if “onlie” had been spelt with an e between the n and the l, as was usual, the number of letters would have been 145, with the wrong factors, so that particular e had to be omitted.

It is interesting that the three sections of the name read down-up-down, rather as in the examples I gave earlier. All the same, I feel sure that the cryptographer would have liked to have got WR joined up with IOTH, to make WRIOTH, in the column next to ESLEY. Presumably he just couldn’t find the right words for the last two lines of the text to achieve this, and had to be content with leaving them offset. If only he had succeeded, it would now be self-evident that the full name had been deliberately ciphered into the Dedication. By the way, if you are thinking that the name HENRY may be somewhat suspect because it doesn’t appear in a perfect rectangle, it can also be found along a diagonal in an array with 9 rows of 16 letters––a perfect rectangle.

The big question, of course, is whether the name HENRY WRIOTHESLEY (or indeed the 5-word message) really is the genuine solution of a genuine cryptogram, or some strange accident of chance. It may be that we are just reading something out of these arrays that isn’t really there, rather as Hotson convinced himself that HATLIV had been coded into the text. I will just give two lines of approach which suggest that the name HENRY WRIOTHESLEY really was deliberately encoded into the Dedication.

The first is to examine all the arrays, from 6 letters wide to 30, and see how many words there are of various lengths. Reading downwards in these arrays, there are 180 three-letter words, 42 four-letter words, but only three 5-letter words, ie HENRY, WASTE, and TRESS, plus the obvious 5-letter segment ESLEY. So out of these four 5-letter words or segments, two are used in the full name HENRY WRIOTHESLEY. This is very strong evidence for deliberate concealment. It seems that the cryptographer realized that the segments had to be as long as possible, to ensure both that the name would be recognised and that it would be taken seriously. Three- or four-letter segments would have been no use for his purpose, because the name might then never get spotted, and even if it were spotted, it would be impossible for the solver to tell whether chance was at work or a cryptographer.

The other method concerns the odds of the full name turning up accidentally. Without going into the details, the odds of HENRY turning up in any array are about 1 in 1000, and the odds of WRIOTHESLEY turning up in any three fragments similar to (and including) ESLEY, WR, IOTH, all in the same array, are about one in 20,000. So the chances of the full name turning up accidentally in these two arrays is the product of the separate odds, ie one in 20 million.

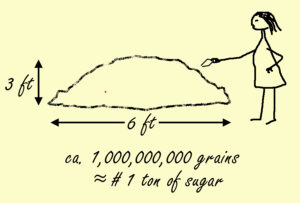

These odds would be much the same for any name consisting of a 5-letter first name and an 11-letter second name, split up in a similar way––just for example, FELIX MENDELSSOHN (rather ahead of his time). But we are considering the proposition that the Dedication might be a cryptogram, and so the fact that the name found is the person most scholars already believe to be “the Fair Youth” of the Sonnets and “Mr. W. H.,” makes it much more probable that it really does contain a genuine cipher. Chance would have had to work extra hard (as it were) to get by far the most likely person into the text. With a very vague figure of one in 100 on this part of the argument, we arrive at an overall figure of very roughly one in two billion for the very small possibility that the result is an accident of chance.

It is quite hard to envisage what this means, so after grappling with a packet of sugar and some letter scales, I worked out that a ton of sugar contains about one billion grains, and it forms a heap about six feet across and three feet high. Now imagine that one of the grains is colored red, you are given a pair of tweezers, and you have to pick out the red grain at your first attempt. (I forgot to say that you are also blindfolded.) That represents odds of one in one billion. As for HENRY WRIOTHESLEY in the Dedication, there are two such piles. First you will have to choose the right pile––and then find the red grain.

There is now, in my view, no doubt whatever that the name of Henry Wriothesley, Third Earl of Southampton, was deliberately recorded in the Dedication, and very little room for doubt that this was in order to record the fact that he was indeed “the onlie begetter . . . Mr. W. H.” and “the Fair Youth” of the Sonnets. It could be argued that his name was recorded in the Dedication for some other reason, but that seems to me to be highly unlikely. The Sonnets promise the Fair Youth immortality in several sonnets, and yet they offer no clue as to who he was; one even gets the impression that any sonnet which came close to revealing his name would have been dropped from the printed series. Consequently, it seems entirely appropriate that the Dedication should supply what is missing from “these insuing Sonnets.” The young man’s name was presumably put there by someone who was determined that he would eventually be identified, to claim at long last the immortality the poet had conferred upon him. Personally, I find it very satisfying that one of the chief mysteries of the Sonnets should find its solution in the Dedication, printed between the title page and the first sonnet.

But perhaps the Dedication has another mystery folded within it. What about the 5-word message we started out with? What is the likelihood that that is authentic? The message was found, as we saw, by counting words, the idea of counting being suggested by the full-stops after every word. The only other explanation ever offered for the full-stops is that they are there in imitation of a Roman inscription chiselled into a stone slab. But if one examines Roman inscriptions, they differ from the Dedication layout in several ways. This is how the Dedication would look if it were laid out as a Roman monumental inscription (right). You can see that the full-stops are in the middle of the type area, rather than on the printing line, and there are stops at the beginning as well as at the end of each line. This suggests that the full-stops in the Dedication are not there in imitation of a Roman stone monument, and may be there for some other purpose. As I mentioned before, when I first had the idea of counting words, it seemed intuitively obvious that the stops were there to indicate that each word and letter was to be counted separately. Thus “Mr.W. H.” counted as three words, not one, and “ever-living” and “well-wishing” each counted as two. Without the stops, one would probably count each of these as one word each, and so miss the message.

Now, the message was found by counting through using the key 6-2-4, derived from the layout, which produced a short but (dare I say) intriguing message. When I first did this, I thought that it must be quite common to find possible messages in this sort of way, and that was why I was so ready to believe that the message was simply a chance sequence of words. Eventually I decided to put this to the test. I started counting through paragraphs of books I happened to be reading, every now and then, in order to see how often 6-2-4 turned up a meaningful 5-word sentence or remark, not knowing whether it would be one in 10 or one in 100 or whatever.

Now, the message was found by counting through using the key 6-2-4, derived from the layout, which produced a short but (dare I say) intriguing message. When I first did this, I thought that it must be quite common to find possible messages in this sort of way, and that was why I was so ready to believe that the message was simply a chance sequence of words. Eventually I decided to put this to the test. I started counting through paragraphs of books I happened to be reading, every now and then, in order to see how often 6-2-4 turned up a meaningful 5-word sentence or remark, not knowing whether it would be one in 10 or one in 100 or whatever.

Well, after several years, and many thousands of paragraphs, probably well over 20 thousand, I have only found one sentence that even remotely made any sense at all. I will give it to you for your edification: “London was not built before.” It comes out of Boswell’s Life of Johnson, and has not the slightest relevance to the rest of the paragraph. Using this experimental evidence as a basis, I worked out that the odds that the message was a chance finding were roughly one in 100 million. Not as remote a possibility as finding the name Henry Wriothesley, but still pretty remote.

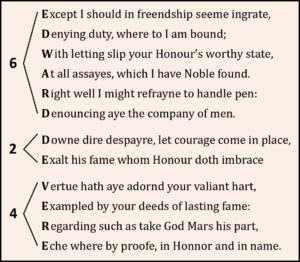

But I had overlooked something, which reduces the odds by a factor of 100, to one in ten billion. Take yet another look at the Dedication. Does the layout perhaps remind you of anything? If you look at the acrostic poem by Anthony Munday, (right), you will immediately see that the 6-2-4 layout of the Dedication corresponds exactly to the name Edward de Vere.

But I had overlooked something, which reduces the odds by a factor of 100, to one in ten billion. Take yet another look at the Dedication. Does the layout perhaps remind you of anything? If you look at the acrostic poem by Anthony Munday, (right), you will immediately see that the 6-2-4 layout of the Dedication corresponds exactly to the name Edward de Vere.

So it seems that our cryptographer chose the name Edward de Vere as his keyword (in modern cryptographic parlance), and derived from it the three numbers 6-2-4 to provide the numerical key to the ciphered message. In this simple way, it would appear, he provides us with confirmation that we have correctly deciphered the message, and correctly identified EVER with E. Ver, Edward deVere.

As an aside, I am sometimes asked why it is that the Dedication––which looks so like a cipher that one expert remarked that it cannot possibly be one!––has not been solved until now. Part of the answer must lie in the fact that editors, both in the past and at the present time, have felt free to alter the spelling, layout and punctuation of the text in a wide variety of ways. That this has resulted in the destruction of essential aspects of the ciphers, rendering their solution im-possible, is shown by the examples given on the following pages.

In conclusion, I would like to suggest (no more) that the mysterious Dedication to Shake-speare’s Sonnets is a masterpiece of cryptography, and records for posterity two tremendous secrets: the name of the true poet, and the name of the young man he was so certain he had immortalized in his verse, before the indifference of history decreed otherwise.

This article is the text of a talk given by Dr. Rollett at the Annual General Meeting of the De Vere Society, London, January 1998, at the Shakespeare Oxford Society Conference, San Francisco, November 1998, and at the Third Edward de Vere Studies Conference, Portland, April 1999. The ciphers themselves are discussed in depth in the author’s paper, “The Dedication to Shakespeare’s Sonnets,” published in The Elizabethan Review, volume 5, number 2, Autumn 1997. Part I of this paper, “Mr. W.H. Revealed at Last,” was the subject of an article by the Science Editor of The Times, December 31st 1997. It had previously been recommended for publication in a leading academic journal by four experts in cryptography from American Academia and Intelligence (the National Security Agency).

The following are arrangements of the dedication to The Sonnets by various authors.