Rough Winds Do Shake: A Fresh Look at the Tudor Rose Theory

by Diana Price

(Editorial Note: This article was originally published in The Elizabethan Review, vol. 4, no. 2, p. 4 (August 1996) (PDF available here), and republished here on the SOF website, April 24, 2019, by permission of the author and publisher.)

The Tudor Rose theory was introduced in the 1930s by Capt. B.M. Ward and Percy Allen, independently advanced by Charlton and Dorothy Ogborn in This Star of England (1952), and further promoted by Elisabeth Sears, who published Shakespeare and the Tudor Rose in 1990. Over the years, the hypothesis has been discussed in the Shakespeare Fellowship Newsletter and its descendant, the Shakespeare Oxford Newsletter.

The theory postulates that Edward de Vere, whom Oxfordians believe wrote the works of Shakespeare, was either secretly betrothed, such betrothal being tantamount to marriage, or indeed actually was married to Queen Elizabeth, and that their union produced a baby in 1574. The theory further supposes that the baby was placed in the Southampton household as a substitute for the son known to have been born to the Southamptons the previous October; that this “changeling” baby grew up as Henry Wriothesley, third Earl of Southampton; that Henry was heir to the throne; that de Vere identified himself as Edward VII; and that Southampton relinquished his claim to the throne in a secret meeting with King James on the night that Oxford died.

Some adherents of the Tudor Rose theory also suppose that William Cecil, Lord Burghley, impregnated his own daughter Anne, Oxford’s wife. This adjunct theory of incest on the part of Cecil exonerates Oxford from promoting an incestuous marriage between Southampton, supposedly his own son, and Elizabeth Vere, supposedly not his own daughter.

Proponents believe that the Tudor Rose theory provides the key to solving many mysteries in Shakespeare’s sonnets and plays, and in particular that the pervasive Rose imagery symbolizes Southampton as the rightful heir to the Tudor throne. Most of the “evidence” supporting the Tudor Rose theory is found in the interpretation of lines selected from Shakespeare’s sonnets and plays, and those lines are quoted to excellent effect. But the Tudor Rose theory is one of many conjectural interpretations of the Shakespeare canon, and interpretative evidence does not carry the same weight as documentary evidence. However, the Tudor Rose theory (sometimes called the Prince Tudor Theory) appears to have some factual underpinnings, as the Ogburns and Sears have cited reputable historians and documents to support their case. This article examines the principal historical evidence they presented.

The Royal Pregnancy

The Ogburns and Sears postulated that Queen Elizabeth gave birth to a son in May or June of 1574. Their theory will need to overcome one seemingly insurmountable problem: Elizabeth’s proposed pregnancy. One would not reasonably expect to find documentary evidence of a clandestine royal birth, but if one found evidence that precluded the possibility of the alleged final trimester and delivery, then the entire theory would collapse. This section investigates the evidence that has been cited to show that Elizabeth delivered a baby and shows where it is in error. It also presents new evidence to prove that Elizabeth had no opportunity to carry and deliver a baby. Sears (1–2), relying largely on the Ogburns’ research, presented her case:

In May of the year 1574, however, Queen Elizabeth, just starting out on her summer procession, surprisingly interrupted her Royal Progress and dismissed her retinue. Ordering Lord Burghley to remain in London, she retired to Havering-attre-Bowre…

… The Queen and her favorite, the young Earl of Oxford, retired to Havering. There they remained in seclusion for several weeks before the Queen resumed her Royal Progress early in July.

Although there is no other official of this period from the end of May to July, there is circumstantial evidence that a child was born to the Queen and the Earl of Oxford at this time.

The Ogburns (834–5) believed that

The child was born in June. The Queen had been “apprehensive” and “melancholy”; she had sent both Hatton and the great court-physician, Dr. Julio, to the Continent; and she refused to see her chief ministers. Of course, one can scarcely expect to find a more definite record than this!

They also quoted a letter written on June 28, 1574 by Lord Talbot to his father, the Earl of Shrewsbury:

The Queen remaineth sad and pensive in the month of June…[it seemed] she was so troubled for some important matters then before her. It was thought she would go to Bristow [Bristol.] … Mr. Hattoun (not well in health) took this opportunity to get leave to go to the Spaw, and Dr. Julio [the Queen’s court physician] with him, whereat the Queen shewed herself very pensive, and very unwilling to grant him leave, for he was her favourite.

The Ogburns supposed that Elizabeth “feigned” her unwillingness to part with Hatton but in fact wanted to get him out of the way when she delivered. The Ogburns cited John Nichols (Progresses, 1:388) as the source of their information, but Nichols’s account is wrong. The same account appears practically verbatim in John Strype’s Annals. (Strype published the first of several editions of his historical narratives for the years in question in 1735–7. Nichols first published progresses in 1788, and his 1823 edition cites Strype.) Like many historians of their era, Strype and Nichols took liberties with their material, co-mingling original texts with commentary and failing to include punctuation that would make it easy for the reader to tell which words were theirs and which were Talbot’s.

Some of what has passed for Talbot’s letter is actually commentary by Strype/Nichols. Furthermore, the information about Hatton is found in a letter written, not in 1574, but in 1573, when Francis (not Gilbert) Talbot wrote that

There is some taulcke of a progres to Bristo … Mr. Hattoun be reason of his great syckenes is minded to gowe to the Spawe for the better recoverie of his healthe.

Strype and Nichols conflated some of the contents of this May 1573 letter with those written in June 1574. Sir Harris Nicolas, in his 1847 biography of Hatton (24), set the record straight concerning Hatton’s trip to the Spa. (The Ogburns listed Nicolas in their bibliography but apparently overlooked the relevant footnote.) Hatton’s departure for the Continent is a matter of record. On May 29, 1573, the privy Council granted him permission to travel, and Hatton sent a number of letters to the Queen from abroad; one dated August 10 refers both to his improved condition and to Dr. Julio (Brooks, 98). Hatton did not travel to the Continent in 1574.

The Ogburns relied on Nichols’s faulty account of events in May and June 1574 to support their version of the Tudor Rose theory. Here then is that faulty account, with original punctuation retained, but split into separate paragraphs to differentiate the sources:

PARAPHRASE OF FRANCIS TALBOT’S LETTER OF JUNE 28, 1574 The Queen remained sad and pensive in the month of June:

STRYPE’S / NICHOLS’S COMMENTARY and so the Earl of Shrewsbury’s Son, then at Court, wrote to his Father, as Leicester also had done;

PARAPHRASE OF FRANCIS TALBOT’S LETTER OF JUNE 28, 1574 and that is should seem she was so troubled for some important matters then before her4.

STRYPE’S / NICHOLS’S COMMENTARY But, notwithstanding, that month she began her Progress; which perhaps might divert her.

PARAPHRASE OF FRANCIS TALBOT’S LETTER OF MAY 10, 1574 It was thought she would go to Bristow. The gests were making in order thereto.

PARAPHRASE OF FRANCIS TALBOT’S LETTER OF MAY 23, 1573 Mr. Hatton (not well in health) took this opportunity to get leave to go to the Spaw;

STRYPE’S / NICHOLS’S COMMENTARY RELATING TO MAY & JUNE, 1573 and Dr. Julio (a great Court Physician) with him: wherat the Queen shewed herself very pensive; and very unwilling to grant him leave; for he was a favourite

STRYPE’S / NICHOLS’S COMMENTARY These are some of the contents of a private letter of the Lord Talbot to the Earl his Father;

STRYPE’S / NICHOLS’S PARAPHRASE OF UNKNOWN SOURCE AND COMMENTARY as also, that the Lord Treasurer [Cecil] intending to wait upon the Queen when she came to Woodstock [July 24–Aug. 2, 1574], as she had appointed him, Secretary Walsingham signified to him, that the Queen now had a disposition, that he, with the Lord Keeper and Sir Ralph Sadler, Chancellor of the Exchequer, should tarry at London; the cause wherefore was unknown to the Lord Treasurer, but seemed to be a surprize to him: but, he said, he would do as he was commanded. The Queen seemed to be apprehensive of some dangers in her absence (which might give occasion to her melancholy), and therefore thought it advisable for those staid Counsellors to remain behind5.

4. Unpublished Talbot Papers. 5. Strype’s Annals.

Hatton’s departure must be deleted from any account of events in 1574, and with it the Queen’s melancholy over his leave-taking (“whereat the Queen shewed herself very pensive, and very unwilling to grant him leave, for he was her favourite”). Yet on June 28, 1574, Francis Talbot wrote a letter from Greenwich (Talbot [1984], Mircoform, vol. 3197) reporting that

The Q Matie hathe bene malencholy disposed a good while wch should seme that she is troubled wth weygti causes. She beginneth hir progres one Wedensdeay next.

(Francis goes on to write about his wife, who is at Wilton, and about a “nag” that he hopes his father will find “fit for your saddl.” There is nothing in this letter about absentee councilors.) Strype and Nichols mistakenly associated Elizabeth’s melancholy of 1574 with Hatton’s departure for the Spa in 1573, so if Elizabeth was “melancholy” in June 1574, then we must look for another reason.

Sears (2) quoted the Ogburns (who quoted Nichols who quoted Strype who paraphrased Francis Talbot’s letter of June 28) to document Elizabeth’s “odd behavior,” implying that her “sad and pensive” mood in June was somehow connected to her expectant condition. Other documentation reveals the reason behind Elizabeth’s melancholy, and it had nothing to do with clandestine childbirth.

On May 30, Charles IX of France died. On June 3, Francis Walsingham was informed of his death, and Elizabeth referred to the event in her letter of June 4 to the Regent of Scotland (CSP-F, 10:509). On June 8, the French ambassador, de la mothe Fénélon, made his official report to Elizabeth. Fénélon wrote in his dispatch of June 18 that he had duly reported the news to Elizabeth and that she had to be consoled. Five days had then passed without another audience, but Sussex, the Lord Chamberlain, informed Fénélon that Elizabeth would receive him the following morning. By June 21, Fénélon had evidently seen the Queen again, since he was able to report on that date that she had personally given and received expressions of condolence.

According to biographer Anne Somerset (283), “the death of Charles IX threw Anglo-French relations into fresh confusion.” His death destabilized Elizabeth’s marriage negotiations with the Duke D’Alençon and her related maneuvers to play Spain off against France. Fénélon (6:140–1) reported to the Queen Regent, Catherine de Medici, that by June 13, Elizabeth had convened members of the Privy Council several times to consider the implications for Anglo-French relations and matters of protocol over the King’s death:

Madame, at the end of the letter of the 8th that I wrote to you, I mentioned the honorable [office] that that princess caused to be sent to me concerning the passing away of the late king, your son, to advise me of the sorrow and unhappiness that she felt; which has persisted since then, and continues to demonstrate how infinitely she misses him; and even, my having sent to ask of the said Lady when it would be her pleasure that I might seek her out concerning a communication that I received from Your Majesty, she contacted me to beg me to spare her some of the grief that seeing me she knew well would renew itself, that she feels her heart to be so burdened by the original reception of this tragic news that it would not be possible for her to endure, in addition, this second condolence from Your Majesty ….

And I shall say nevertheless, Madame, that this princess has several times assembled her council to deliberate what she must do, and how she shall act in her present affairs, following this great accident of the death of the King.

On June 18, Fénélon (6:145) described her “extreme regret at the passing of the late king.” On June 21, he wrote (6:153) that Elizabeth met him “with a face strongly composed in a state of sorrow” over the death of her fellow monarch. On July 1, he reported that she had again “assembled her council.”

According to these dispatches, Elizabeth sought the advice of her council to be sure that she comported herself properly through a period of official mourning. Fénélon reported that there were differing opinions within her council as to how she should behave. Perhaps on June 13, Elizabeth deferred her next audience with Fénélon not so much because she was overwhelmed with grief, but because she needed to buy more time in which to further consult with her councilors.

However, Elizabeth’s intention to sojourn at Havering in May 1574 is documented in a letter by Francis (not Gilbert) Talbot of May 10, 1574 (Hunter, 112):

The quene matie gouethe of Saterdeay cum senight to Havering of the bower and their remeaneth tyle shee begins her progress wch is to Bristo.

On May 10, then, Talbot was under the impression that the Queen was planning to go to Havering in about a week. Talbot also mentioned that the Queen had spoken with him personally on inconsequential subjects but he made no note of her mood nor of anything out of the ordinary with respect to her appearance.

The Quenes matie hathe spoken to me, and tould me of your Lo.’ letter wch I brought; and howe well shee did accept it; wth manie comfortable wourds: but no thinge of anie matter.

According to the Tudor Rose theory , on May 10, Elizabeth would have been in her ninth month.

Sears (2) used Talbot’s letter to claim that the Queen and Oxford remained “in seclusion [at Havering] for several weeks before the Queen resumed her Royal Progress early in July,” that is, from mid-May to the latter part of June. She also informed her readers that

Although there is no other official record of this period from the end of May to July, there is circumstantial evidence that a child was born to the Queen and the Earl of Oxford at this time.

But an official record shows that Elizabeth cannot have been in seclusion on May 18, because on that date she sent two letters on political and military matters to the Lord Deputy of Ireland (CSP-I, 23). She sent an official letter on June 4 from Hampton Court to the Regent of Scotland (CSP-F, 10:509) and another to Ireland on June 15 from Greenwich (CSP-I, 29). She was at Greenwich on June 28, when Gilbert Talbot reported from court that “Her matie styrreth litell abrode,” a statement that suggests Elizabeth remained at Greenwich from June 15 until the end of the month. On June 30, the Queen moved with the court from Greenwich to Richmond, and her known progress throughout July rules out delivery after the end of June.

Contrary to Sears’s statement that there is “no other official record of this period,” there are in fact numerous other records documenting Elizabeth’s whereabouts and activities during May and June, the most critical being those written by Fénélon. However, before seeing what more Fénélon had to say, let us look at one of Burghley’s papers dated a few months earlier.

Concerning the continuing marriage negotiations between Elizabeth and the Duke d’ Alençon, Burghley’s papers (Murdin, 2:775) show that on March 16, 1574, “The Queen granted a salve conduct for Mons. D. Alenson to come into England any time before the 21st of May.” (In a letter of February 3, 1574 to her ambassador in Paris [Harrison, 121–2], Elizabeth had suggested that perhaps Alençon should come “over in some disguised sort.”) The wording of the March 16 Safe Conduct (CSP-F, 10:477), i.e. that “he may make his repair to her at a convenient time after she be advertised of his arrival,” shows that the Queen expected to meet with Alençon personally, at which time the marriage negotiations might be facilitated, or so the French were led to believe. It further shows that he was granted permission to land at any British port before May 20.

Therefore, allowing for additional overland travel time, Alençon might be expected to arrive at court in London or on progress any time after the first of April and before the end of May. (In April, Catherine de Medici placed Alençon under restraint in Paris; he remained under house arrest for some time, fell ill, and did not visit England in 1574. But on March 16, Elizabeth had no reason to doubt that the Safe Conduct would ensure Alençon’s personal visit to her.) On the day the Safe Conduct was issued, Elizabeth would have been, according to the Tudor Rose theory, nearly seven months pregnant.

Somerset (101) pointed out that Elizabeth had virtually no privacy, and a pregnancy any time after her accession would have been extremely difficult to conceal. If the prospective royal consort was invited to come into the Queen’s presence any time during the final run-up to her delivery, then historians will have to reconstruct the nature of the marriage negotiations and Elizabeth’s weight. If her appetite was modest (Somerset, 350, 377) and her constitution strong and athletic, and if her portraits did not routinely take a hundred or so pounds off of her figure, then Elizabeth was not a good candidate for concealing pregnancy.

As we saw, on May 10 Francis Talbot wrote from court that the Queen had spoken personally with him. As she entered her ninth month, then, she was still freely circulating at court for all to see. Fénélon reported on April 2, 24, May 3, 10, 16, 23, and June 8, 13, and 21 that he had had a personal audience with Elizabeth, so she was repeatedly on display before the French ambassador when she was supposedly in the final trimester of her pregnancy.

If Elizabeth gave birth in late May or June, then the ambassador had audience with her no less than 15 days (the longest interval between interviews) prior to delivery. A rather substantial stretch of the imagination is required to envision just how Elizabeth concealed her condition from everybody at court, including Fénélon.

The alternative is to suppose that Fénélon knew full well she was pregnant and edited his reports to the formidable Queen Regent, Catherine de Medici. On May 16, Fénélon seems to have been anxious to re-assure his employer that Elizabeth looked on her prospective bridegroom with favor, even though she was playing hard-to-get. He reported to the Queen Regent that Elizabeth

has no bad impression of Monsieur the Duke, your son. She replied to me that she did not wish to be so ungracious as to have a poor estimation of a prince who showed admiration of her; but this I tell you emphatically, she broke into a smile, that she would take no husband, even with her legs in irons [shackles].

Everything in Fénélon’s dispatches reflect the skilled tactics of a professional diplomat, respectful of the role he played between two powerful women. Fénélon would hardly have run the risk of deliberately concealing critical information from his employer, especially since news of such a visually obvious and sensational impediment to the marriage negotiations might easily reach the French court from an independent source.

Sears tells us that the Queen and Oxford went into seclusion at Havering for Elizabeth’s delivery. As we have seen, the record of official correspondence shows that the intended sojourn to Havering in May was evidently postponed, but Fénélon’s correspondence again sheds some light on the matter. In his June 13 letter to the Queen Regent (6:141), he wrote that Elizabeth

was to depart immediately from Greenwich, to relieve somewhat her distress as best she could, in a dwelling of hers by the name of Havering, in the countryside, to which I could send my secretary three days from now, and that she could summon me there when she shall find time for me to come to see her.

In the post script to this same dispatch (6:144), Fénélon reported that Elizabeth deferred trip to Havering because of a political crisis:

I had scarcely signed this [letter], when a communication arrived [just in time] from that court, saying that yesterday evening Doctor Dale’s secretary had arrived from one direction, and news from Spain from the other that stated that the Spanish force will undoubtedly depart at the end of this month, with 250 armed ships, the security of her affairs that that princess thought existed has suddenly been converted to new suspicions. And notwithstanding that the baggage was already on its way to Havering, she has ordered it back, and having postponed this trip for three weeks, assembled her council hastily; the outcome of which was a command that the naval officers diligently set about executing the original order; and dispatched the Earl of Derby to muster men and mariners in his area; and … milord Sidney to cross promptly to Ireland ….

According to this dispatch, Elizabeth and her entourage were intercepted at the outset of the trip with disturbing news from foreign courts. These reports put immediate pressure on Elizabeth to further secure the coasts against possible Spanish attack. So she postponed her sojourn to Havering and remained instead at Greenwich to deal with the crisis, even though her staff had already started out with the luggage.

The options facing proponents of the Tudor Rose theory are not good. If Elizabeth granted Alençon a Safe Conduct in March that guaranteed him access to the Royal presence any time over the next 75 days, then either Elizabeth did not know she was pregnant in March, or she did not care if the duke visited her when she was obviously in the family way. Nor did she care if she regularly exposed herself in that condition to the French ambassador. Fénélon’s May and June correspondence convey a business-as-usual atmosphere and confirm his regular personal interaction with the Queen.

Can we seriously imagine that Elizabeth would have compromised her marital chess game, so vital to her country’s security, by recklessly presenting herself as an expectant mother to a potential prince consort or his emissary? Even Sears (9-10) wrote that Elizabeth “used ‘marriage negotiations’ with the Duc d’ Alençon to disrupt relations between France and Spain …. Had the French suspected that she had a Consort and an heir, the combined forces of France and Spain might have attacked England.”

What better way for Elizabeth to jeopardize the very stability and security of England than by appearing pregnant — right up through her final trimester — before courtiers, councilors, and a foreign diplomat negotiating for her hand in marriage?

Elizabeth’s whereabouts in May and June 1574 are amply accounted for. Contrary to claims that Elizabeth “dismissed her retinue” in May and spent June in seclusion, her continuing accessibility to and interaction with members of her Privy Council, the French ambassador, and courtiers are matters of record. There is no realistic window of opportunity in either month that would permit her a confinement and child-bearing interlude at Havering or elsewhere. More to the point, there is no window of opportunity for her final trimester. Dispatches show that she consulted with her advisors on matters of protocol following the death of the French king, and that she consequently observed a period of mourning for her fellow monarch, fully explaining her “melancholy” of June 1574. Her trip to Havering is known to have been postponed due to a crisis in foreign affairs.

Anyone wishing to further promote the Tudor Rose theory may wish to propose an alternative timetable for the royal pregnancy and delivery, preferably one unencumbered by letters, state papers or dispatches detailing Elizabeth’s activities and official audiences.

Assumptions and Errors

ROSE IMAGERY

Even if an alternative timetable is identified to accommodate Elizabeth’s supposed confinement, proponents of the Tudor Rose theory will still be burdened with many other problems. The meaning attached to the Tudor rose imagery in Shakespeare’s sonnets is an example. The Tudor rose was used to symbolize the British crown (Fox-Davies, 269):

Under the Tudor sovereigns, the heraldic rose often shows a double row of petals, a fact which is doubtless accounted for by the then increasing familiarity with the cultivated variety, and also by the attempt to conjoin the rival emblems of the warring factions of York [the white rose] and Lancaster [the red rose].

Sears assumed that Shakespeare personified Henry Wriothesley as the Rose of the sonnets to signify his royal parentage. Specifically, Sears (8) finds Henry’s royal lineage described in sonnet #35, which

introduces the play on “canker” meaning a wild rose, or eglantine, the Tudor rose, that is growing untended by his parents [i.e. Oxford and Elizabeth]. “Sweetest bud” indicates that a child is referred to, an immature Tudor rose.

Later, Sears (51) explained that “Henry, being young, though representative of the Tudor Rose, is still only a bud that will burst into full bloom when he becomes King.” But it is not necessary to transfuse royal blood into Henry Wriothesley in order to explain his association with rose imagery. Martin Green, one of many traditional Shakespeareans who have supposed that Henry was the Rose of the Sonnets, showed that the Southamptons adopted the Tudor rose as a motif three generations earlier.

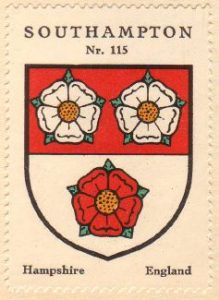

According to A.C. Fox-Davies, author of A Complete Guide to Heraldry (270, Plate VII), “amongst the scores of English arms in which the rose figures, it will be found in the original heraldic form in the case of the arms of Southampton.” (The Tudor rose was clearly not used exclusively by the monarchy; three roses also appear on the escutcheon for the Darcy family, as published in Christopher Saxton’s 1579 Atlas of 16th Century Maps.) The escutcheon designed for the town of Southampton is comprised of three Tudor roses (Figure 1), and Green (25) discovered that this escutcheon “had an intense personal and dynastic meaning for the man who placed them in his home.” That man was Henry’s great-grandfather, Thomas Wriothesley. Thomas acquired Titchfield Abbey in December 1537 and converted it into his principal residence over the next few years. Although the Abbey is today in ruins, most of the shield of the town of Southhampton can still be seen carved over a door on a surviving wall (Green, 23, 170). This carving dates from the conversion of Titchfield c. 1540, and Wriothesley’s reasons for adopting the arms of the town of Southampton relate to his high-powered career under Henry VIII; these reasons are fully detailed by Green.

Those who propose that Henry Wriothesley was the Rose of Shakespeare’s sonnets need look no further than his great-grandfathers’ personal appropriation of the coat of arms of the town of Southampton to explain his family’s identification with the Tudor rose. The rose symbolized the political and geographic influence of the Wriothesleys.

OXFORD’S SIGNATURE

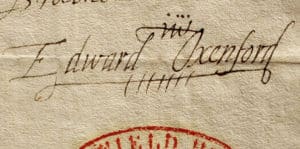

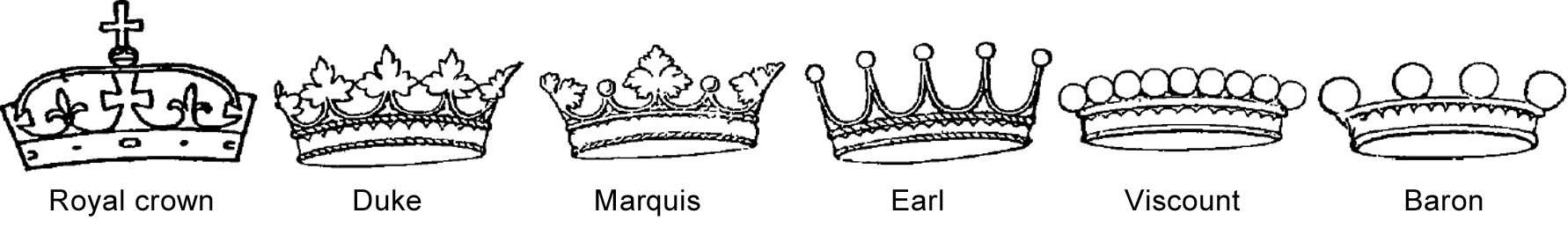

Sears (3) used Oxford’s so-called “crown signature,” with its crown-like symbol and seven tick marks (Fig. 2), to show that Oxford viewed himself as the royal consort, Edward VII:

there is the even stronger possibility that the Queen and Oxford were married in 1569 when he was nineteen and she was thirty-six. Surely a betrothal would not warrant a royal signature; only an actual marriage would have given him the right to sign his name, (King) Edward (VII) Oxenford, as indicated in the holograph signature.

Oxford’s signature would more appropriate be called the “coronet signature,” because it depicts spikes topped with little balls, emanating from the headband, signifying the coronet of earldom (Fig. 3). The name subscribed with a horizontal bar signifying ten, cut through with seven tick marks, all adding up to Oxford’s rank as 17th earl. Oxford’s personal use of the coronet, an authorized symbol of rank is not equivalent to an unauthorized use of the monarch’s coat of arms, which is the comparison Sears made in The Tudor Rose.

THE CHANGELING SON

The Tudor Rose theory has been beleaguered by numerous errors that have been passed off as facts to support it. Sears (10) informed her readers that the son born to the Southamptons in October 1573 died, making it possible for Elizabeth and Oxford’s son, born the following May/June, to be substituted in the Southhampton household for upbringing. Sears (10–11) cited Charlotte Stopes and G.P.V. Akrigg to confirm her theory about the changeling baby who replaced the Southampton’s son:

Though there is no record of this child’s death, it has been reported that Henry Wriothesley was the second son. Akrigg reports that Henry’s brother died young, before Henry became a ward of the Crown. British historian and biographer of the Third Earl of Southampton, Charlotte Stopes, searched the records carefully but could not solve the mystery. Mrs Stopes…only compounded the mystery by finding that, though there were two sons born to the Wriothesleys, there was no record of the birth of the second, nor the death of the first.

Stopes and Akrigg are credible authorities, and Sears lends weight to her argument by citing their findings. But here is what Stopes (2) actually wrote:

Thus was the only son2 of the second Earl of Southampton born…

2. It has always been said that he was “the second son,” but there is no authority for that. The error must have begun in confusing the second with the first Henry.

Akrigg (12) made no mention of a mysterious second son, but he did report

that an elder sister, Jane, died at some indeterminate period, perhaps even before young Harry (as he was called) was born, but he had another sister, Mary, a little older than himself, for a companion.

Neither biographer wrote what Sears claimed they wrote.

ROWLAND WHYTE’S LETTER

Sears misquoted numerous sources. For example, she probably got the attention of many readers by citing a letter written by an Elizabethan who used a recognizable phrase from Hamlet to describe Henry Wriothesley, the alleged Tudor Rose (60):

Rowland Whyte, writing Court gossip in late September of 1595, notes:

My Lord of Southampton doth with to(o) much Familiarity court the faire Mistress Vernon…Her friends might well warn her that Southampton was indeed ‘a prince out of thy star.’

Sears cited Akrigg as her source. But Whyte wrote only the first sentence; biographer G.P.V. Akrigg wrote the second. Akrigg had quoted the first sentence of Whyte’s letter as above, and then went on to comment on the realities of marriage negotiations among the titled classes (48-9):

Mistress Vernon would be lucky if she picked up a knight for her husband. Her friends might well warn her that Southampton was indeed ‘a price out of thy star’. His ardent and all too obvious attentions could only detract from reputation and spoil her chances of making a reasonably good match elsewhere.

Akrigg had used the phrase from Hamlet to illuminate his discussion, but Sears inserted his comment into text presented as Whyte’s letter.

THE PEYTON REPORT

A 1603 report by Sir John Peyton, Lieutenant of the Tower of London has been quoted to show that the Earl of Oxford continued to hold out hope that Southampton would succeed Elizabeth. According to Payton’s report, two days before the Queen died, Oxford told the Earl of Lincoln about a possible power play for the throne. Lincoln then informed Peyton, and Peyton thought that Lincoln should have coaxed more of the details out of Oxford. Sears (98) cited the following passage to show that the peer who “was meant” to overthrow James was Southampton:

Peyton declared that he was at first much disturbed, but when the Earl [of Lincoln] had made him understand what Peer was meant, Sir John was relieved…

Sears described this incident as Oxford’s “last attempt to have his son proclaimed the Tudor heir,” assuring her readers that the “peer referred to above was, of course, Southampton.” In other words, Sears claimed that Oxford told Lincoln that they should help Southampton take the throne. But Lincoln was not talking about Southampton; he was referring to Oxford. And the words quoted above are not those of Peyton. They were written by an historian named Norreys O’Conor, who transcribed and annotated Peyton’s report from manuscript in 1934.

Neither Sears nor the Ogburns quoted O’Conor’s transcript. They quoted yet another source, William Kittle (160–2), an historian who published some of O’Conor’s material in 1942. The Ogburns footnoted Kittle’s reliance on O’Conor but apparently investigated the matter no further. Kittle’s book was published posthumously, and either he or his editor omitted the essential punctuation that would have distinguished Peyton’s report from O’Conor’s commentary. Kittle’s conflated account was quoted by the Ogburns, and Sears relied on the Ogburns for her citation.

The words that the Ogburns and Sears attributed incorrectly to Payton include the key passage about “what peer was meant.” In fact, O’Conor commented that Peyton was relieved to know that the peer who “was meant” (i.e., the peer who had approached Lincoln about the power play) was only Oxford, who presented no threat in military terms, no matter whom he might suggest to Lincoln as an alternative king. The alternative king whom Oxford proposed was actually Henry Hastings, Lincoln’s grand-nephew. Reference to Gode’s Peace (106–7) allows the reader to differentiate between Peyton’s report and O’Conor’s own commentary. Oxford thought that

PEYTON’S REPORT the Erle of lyncolne ought to have more regard then others, becawse he [Lincoln] had a Nephewe of the bludde [blood] Riiall, nameing my lorde hasteings, whom he perswaded the Erle of lyncolne to send for; and that ther should be means used to convaye hym over into france, wher he shoulde fynde frends that wolde make hym a partye, of the which ther was a president in former tymes. He also…invayed muche agaynst the natyon of scotts! [The Earl of Lincoln] Brake of [off] his discourse, absolutely disavowing all that the great noble man had moved.

O’CONOR’S COMMENTARY Sir John pointed out to Lord Lincoln his folly in silencing the Earl of Oxford before getting all possible information. Peyton declared that he was at first much disturbed, but, when the Earl [of Lincoln] had made him understand what peer was meant, Sir John was relieved for

PEYTON’S REPORT I [Peyton] knewe hym [Oxford] to be so weak in boddy, in frends, in habylytie, and all other means to rayse any combustyon in the state, as I never feered any danger to proseyd from so feeble a fowndation.

O’CONOR’S COMMENTARY This is a delightful comment of the man of action [Peyton] concerning a poet and musician [Oxford].

Peyton’s original report specifically names everyone involved in the incident, and in context, it is obvious that Southampton was not the subject of this report. Readers can easily detect the conflation of texts in The Tudor Rose by looking for shifts between standardized and irregular spelling, or shifts between first and third person.

SOUTHAMPTON’S RELEASE FROM THE TOWER (1603) AND ARREST WHEN OXFORD DIED (1604)

When Queen Elizabeth died in March 1603, Southampton was still imprisoned in the tower of London for his part in the Essex rebellion. One of James’s first official acts upon his accession was to release Southampton; James then restored Southampton’s title and fortunes. Southampton was arrested again on the evening that Oxford died in June 1604, and Sears (101) argued that this arrest proves that Southampton was still a threat to King James:

the moment Oxford died, however, [Robert] Cecil must have acted quickly to alert James that Southampton was free to seize his (Southampton’s) Throne.

But this is pure speculation. Nobody knows whether Southampton’s arrest was related in some way to Oxford’s death. Moreover, the underlying assumptions are flawed. Robert Cecil orchestrated James’s accession to the throne and is further presumed by Sears (75, 101) to have known about Southampton’s royal blood. If Cecil had viewed Southampton as a potential threat to James, would not Cecil have advised James to leave Southampton in the Tower, if not to dispatch him? But at his accession, James released and then empowered his alleged arch-rival.

Conclusions

As attractive as the Tudor Rose theory may be on the interpretive grounds, the historical facts plainly refute it. Indeed, the facts concerning Elizabeth’s and her councilors’ whereabouts in May–June 1574, the matters of state known to have occurred at that time, and Fénélon’s documented personal audiences with her preclude any royal pregnancy, confinement, or clandestine delivery. Sears’s errors, whether misquoting Stopes and Akrigg on Southampton’s birth, or conflating texts (such as Whyte’s letter with Akrigg’s commentary), or paraphrasing sources to suit her purpose (e.g., the information she footnoted on p. 17) are so numerous as to undermine the legitimacy of the theory. Adherents have not constructed their case with a single piece of documentary evidence, and the inaccurate arguments advanced to support the theory serve only to discredit it. Since ample documentation contradicts it, the Tudor Rose theory cannot be viewed as having any substance.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

Judith T. Wozniak, Ph.D., Dept. of History, Cleveland State University, provided summaries in English of Bertrand de Salignac de la Mothe Fénélon’s dispatches for April–July 1574; her translations narrowed the field of my investigation. Tal Wilson of Bodega Bay, CA provided the final translations of extracts quoted in this paper.

APPENDIX:

The Talbot Letters The texts of Francis’s letters of May 23, 1573 and May 10, 1574, and Gilbert’s letter to the Countess of Shrewsbury of June 28, 1574 are taken from Joseph Hunter’s Hallamshire (112). Francis Talbot’s letter of June 28, 1574 is taken from the original manuscript (Talbot, Microform, vol. 3197).

Francis Talbot to the Earl of Shrewsbury: May 23, 1573

Ryght honorable my hu[m]ble deautie reme[m]bred. Meay it please your Lo: I have sent you here inclosed such advertismens as latlie is come oute of France. Oute of Scotlande this is the newes: that Sr George Carye and Sr Harrie Leaye and Captea[n]e Reade goinge to yowe the castell were almost sleane wth a greate pease oute of the castell. The are so feawe wthin as it is thoucht the castle wyll be taken verie shortlie wthoute ane greate trouble. There is some taulcke of a progres to Bristo; but by reason of the unsesonablenes of the yeare, ther is greate meanes made for hure not goinge of so longe a progres; but hure Mati’s greate desire is to gowe to Bristo. Mr Hattoun be reason of his greate syckenes is minded to gowe to the Spawe for the better recoverie of his healthe. All your Lo.’ frinds do well here. My Lord treasurer and my Lord of Lecester do deaylie ascke for your Lo. and howe you have your healthe this springe. This is all that is at this tyme wourthie writinge: wherfore for this tyme I hu[m]blie tacke my leave, craving your Lo.’ delie blessinge. Fro[m] the couert this XXXIIIth of May. Your Lo.’ lovinge and obedient sonne

Francis Talbot to the Earl of Shrewsbury: May 10, 1574

Ryght honorable my hu[m]ble deautie reme[m]bered: meay it please your Lo: I have steayed writinge because I hoped to have hard su[m]thing of Corker; but I can here nothinge. I have dealt with my Lord tresoror and my Lord of Lecester boueth, but I can not learne of them anie thinge that he hathe seayed of late, or done; he remeaneth still in close prison in the Flete. The Quenes matie hathe spoken to me, and tould me of your Lo.’ letter wch I brought; and howe well shee did accept it; wth manie other comfortable wourds; but no thinge of anie matter. The matter of Corker is al[m]ost forgotten here; here is nothinge but of King Philipe cu[m]inge dounne in to Flanders; and preparing the Quen’s navè to seay; but whether my Lord Admiraule goueth himselfe or no it is not given out for serteayne as yet. The quene matie goethe of Saterdeay cum senight to Havering of the bower and their remeaneth tyle shee begins hir progres wch is to Bristo; the gests be not drauen, but shee is deter[m]ined for sertean to gowe to Bristo. This is all wch is wourthie writinge; but as matter shall happen here I wyll God willinge advertes your Lo: accordinge to my deautie. Thus with my deaylie prear to Almightie God for your Lo.’ longe life wth much healthe, I hu[m]blie tacke my leave; cravinge your Lo.’ delie blessinge. Fro the couert at Grinwege this xth of Meay 1574. Your Lo:’ lovinge and moste obedient sonne

Gilbert Talbot to the Countess of Shrewsbury: June 28, 1574

My moste hu[m]ble duty remembred unto your good La: To fulfyll your La.’ co[m]mandement, & in discharge of my duty by wryting, rather then for any matter of importance that I can learne, I here wth troble your La.—Her matie styrreth litell abrode, and since the stay of the navy to sea, here hathe bene all thinges very quieat; and almoste no other taulke but of this late proclamation for apparell, wch is thought shall be very severely executed both here at the cowrte, & at London. I have wrytten to my Lorde of the brute yt is here of his beyng sick agayne, wch I nothing doubte but yt it is utterly untrew: howbeit because I never harde from my L. nor yor La. since I came up, I cannot but chuse but be sumwhat trobled, & yet I consyder the like hathe bene often reported moste falcely, and without cause, as I beseche God this be. My lady Cobham asketh daly how your La. dothe, and yesterday prayed me, the next tyme I wryt, to doe her very hartie co[m]mendacons unto your La. saynge openly she remayneth unto your La. as she was wonte, as unto her deereste frend. My La. Lenox hathe not bene at the cowrte since I came. On Wednesday next I trust (God willing) to goe hence towards Goderidge; and shorteley after to be at Sheffeld. And so most hu[m]bly crave[n]g your La.’ blessing, wt my wonted prayer, for your honor and most perfite helthe lounge to continew. From the cowrte at Grenewidg this XXVIIIth June 1574. Your La.’ most hu[m]ble and obedient sun

Francis Talbot to the Earl of Shrewsbury: June 28, 1574

Ryght honorable my hu[m]ble deautie reme[m]bred meay it please your Lo: I have reseaved your letter by my mane, [Cleaton?] and accordinge to my deutie greatlie rejosd therat and that it pleaseth your Lo: so fatherlie to advise me, touching my journey to the sea, but I never ment to make serte[n] to gowe, nether to have anie charge savinge for experiens onlie to have accu[m]panied my Lord admiraule at this ernest request, wch after that sort beinge alwes on shipbord would have bene no charge at all but nowe all suche prete[n]ces are dasshed and none of hir matie ships goueth and all speche thereof being nowe leayed, all thinges seme quiat at the couert, so as at this present I am unable to advertise your Lo: of anie thinge; The Q mattie hathe bene malencholy disposed a good while wch should seme that she is troubled wth weygti causes. She beginneth hir progres one Wednesdeay next; because of my wyfe’s beinge at Wylton I mene to gowe presentlie thither for anie thinge I knowe yet I thincke not to gowe thens till hir mtie come thither [whby?] it had bene my part to have advertised your Lo: before this but that I was uncertayne of the cu[m]inge up of my horses, I wishe that nagg that your Lo: had of my mane meay be fit for your saddl and then I shall be glad I bought him. I thancke your Lo: hu[m]blie for the other I had for him wth the furniture. / Thus most hu[m]blie cravinge your Lo: delie blessinge, I tacke my leave, fro[m] the couert at Grinwege this xxviij of June / 1574 / Your Lo: loving and most obedient soune

Abbreviations used

CSP-D Calendar of State Papers, Domestic Series, of the Reigns of Edward VI., Mary, Elizabeth 1547-1580

CSP-F Calendar of State Papers, Foreign Series, of the Reign of Elizabeth 1572-1574, vol. 10

CSP-I Calendar of State Papers Relating to Ireland, of the Reign of Elizabeth 1574-1585

SFN The Shakespeare Fellowship Newsletters

Bibliography

Acts of the Privy Council of England, vol. 8. Ed. John Roche Dasent. London, 1894.

Akrigg, G. P. V. Shakespeare and the Earl of Southampton. London: Hamish Hamilton 1968.

Brooks, Eric St. John. Sir Christopher Hatton. London; Jonathan Cape, 1946.

Calendar of State Papers, Domestic Series, of the Reigns of Edward VI, Mary, Elizabeth 1547-1580, Ed. Robert Lemon. London, 1856.

Calendar of State Papers, Foreign Series, of the Reign of Elizabeth 1572-1574, vol. 10. Ed. Allan James Crosby. London, 1876.

Calendar of State Papers Relating to Ireland, of the Reign of Elizabeth 1574-1585. Ed. Hans Claude Hamilton. London, 1867.

Chambers, E. K. The Elizabethan Stage. 4 vols. 1923. Reprint, Oxford: Clarendon Press, 1961.

Fénélon, Bertrand de Salignac de la Mothe. Correspondence Diplomatique. 6 vols. Paris & London, 1840.

Fox-Davies, Arthur Charles. A Complete Guide to Heraldry. New York: Gramercy Books, 1978.

Green, Martin. Wriothesley’s Roses In Shakespeare’s Sonnets, Poems and Plays. Baltimore: Clevedon Books, 1993.

Harrison, G. B. The Letters of Queen Elizabeth. 1935. Reprint of 1968 ed. Westport, CT: Greenwood Press, 1981.

Hope, Warren and Kim Holston. The Shakespeare Controversy: An Analysis of the Claimants to Authorship, and their Champions and Detractors. Jefferson, NC: McFarland & Co., Inc., 1992.

Hume, Martin A. S. The Courtships of Queen Elizabeth. London, 1896. Hunter, Joseph.

Hallamshire: The History and Topography of the Parish of Sheffield in the County of York, etc. London 1869.

Kittle, William. Edward de Vere 17th Early of Oxford and Shakespeare. Baltimore: The Monumental Printing Co., 1942.

Lodge, Edmund. Illustrations of British History, Biography, and Manners, in the Reigns of Henry VIII, Edward VI, Mary, Elizabeth, and James I, etc. 3 vols. London, 1791.

Murdin, William and Samuel Haynes. A Collection of State Papers relating to Affairs In the Reigns of King Henry VIII, King Edward VI, Queen Mary and Queen Elizabeth, From the Year 1542 to 1570. 2 vols. London, 1740.

Nichols, John. The Progresses and Public Processions of Queen Elizabeth, etc. 3 vols. London, 1823.

Nicholas, Sir Harris. Memoirs of the Life and Times of Sir Christopher Hatton. London, 1847.

O’Conor, Norreys Jephson. Godes Peace and the Queenes: Vicissitudes of a House 1539-1615. London: Oxford University Press, 1934.

Ogburn, Dorothy and Charlton. This Star of England. New York: Coward-McCann, Inc., 1952.

Phillipps, G.W. (see Hope & Holston)

Price, Diana. “Oxford’s Coronet Signature.” Shakespeare Oxford Society Newsletter 31:3, summer 1995.

Sears, Elisabeth. Shakespeare and the Tudor Rose. Seattle: Consolidated Press Printing Co. Inc., 1991. Shakespeare Fellowship News-letters, The. September 1953, April 1954.

Stopes, Charlotte Carmichael. The Life of Henry, Third Earl of Southampton, Shakespeare’s Patron. Cambridge: The University Press, 1922.

Strype, John. Annals of the Reformation and Establishment of Religion, etc. 3 vols. Oxford: Claredon Press, 1824.

Talbot Papers. A Calendar of the Shrewsbury and Talbot Papers in Lambeth Palace Library and the College of Arms. Ed. G. R. Batho. 2 vols. London: Her Majesty’s Stationery Office, 1971.

Talbot Papers: Social and Political Affairs in the Age of the Tudors, The. From Lambeth Palace Library, London. Sussex, UK: Harvester Press Microform Publication Ltd., 1984.

Walsingham, Francis. Journal of Sir Francis Walsingham from Dec. 1570 to April 1583. Edited from the original ms. in the possession of Lieut.-Col. Carew, by Charles Trice Martin. London, 1870.

Letters and Responses from Elizabethan Review, Spring 1997—pages 6-17, to the article Rough Winds Do Shake: A Fresh Look at the Tudor Rose Theory by Diane Price.

“Plucking the Tudor Rose”

[highlight][Pp. 7-9 — From Charlton Ogburn, Beaufort, South Carolina][/highlight]

To the Editor:

In “A Fresh Look at the Tudor Rose Theory” (ER, vol. 4, no. 2), Diana Price has proved herself a most admirably thorough sleuth in her determination to disprove the finding that Southampton was the son of Queen Elizabeth and Oxford. That the youth was the fruit of such a union is a proposition I resisted for years for obvious reasons and have come to accept only because I have felt I had no choice. No other scenario of which I have heard accommodates the facts in the case.

Ms. Price, it seems to me, has scored a success in nearly all the challenges she has mounted to what she calls “The Tudor Rose Theory.” The trouble is that these are all focused on subordinate issues while the central considerations are overlooked until at the end, she touches on one and then only to shy away from it. Her argument, unless I mistake her, comes down to denying the possibility of Elizabeth’s concealing a pregnancy during the crucial period and of her being able to bear a child in secret. My response to that is: let her think again.

Plenty of women, I do not doubt, have succeeded in carrying out what Ms. Price maintains the Queen could not have. Given the costumes available to a dame of the period and the sealing of gossipy mouths by the knowledge of what indiscretion could cost, I find no difficulty in believing that the Queen could have borne a child with only a few persons in on it. My mother, I might add, had a print of a full length portrait originally designated as of Queen Elizabeth with the subject looking suspiciously full in the midriff, which she told me was later labeled as simply that of a lady of the Court. (Elizabeth’s pregnancy actually seems to be broadly hinted at in Two Gentlemen of Verona i.e., of One Vere, when a reference is made out of the blue, to Sylvia’s “passing deformity,” the consequence of Valentine’s “present folly.” Please see The Mysterious William Shakespeare (pp. 521-24). We may recall recent reports of the high-school couple in Delaware in which the young girl carried her pregnancy to full term and gave birth to an infant son in a motel without anyone’s ever having been the wiser but for the discovery of the baby in a collection of trash, allegedly done to death by the young father.

How Ms. Price accounts for the terms in which the young poet addresses the young friend of the Sonnets is unclear to me. Yet this is of key significance. I have been unable to explain it except on the basis of the latter’s having been either the poet’s homosexual lover or his son and, somehow, his sovereign — and the evidence against the former interpretation is overwhelming and conclusive. But, given these alternatives, the poet was faced by a terrible dilemma. Fully expecting the fair youth to be identified as Southampton, presumably in a dedication similar to those of Venus and Adonis and Lucrece — “Thy name from hence immortal life shall have” — he could not possibly allow the youth to be seen by posterity as his catamite, while acknowledging him as his son would have been proscribed under the full power of the Crown. His solution? Sonnet 20, making it explicit that the young man, the object of both the poet’s idolatry and censure, could not have been either. Thus, we are left with what A.L. Rowse calls “the greatest puzzle in the history of English literature.” If, as I am constrained to believe—much against my will, I may repeat — that the identification of Shakespeare as Oxford must lead to that of the young friend of the Sonnets as the son of Oxford and Elizabeth, then the need for dissimulation of Oxford’s authorship of Shakespeare’s works was absolutely imperative. It was not simply a matter of preserving the reputations of the Queen and those around her, which would be recognized in the plays were these attributed to an insider at Court, though given the unsparing treatment of some of them this would be reason enough. What was at stake in the identity of the poet-dramatist was the succession to the throne of the United Kingdom. For all I know, this may be dynamite even today.

Let us come now to the events of June 24,1604, which are of critical importance to our story. On that date, Oxford died and King James had the Earl of Southampton clapped in the Tower of London, from which James had released him following Elizabeth’s death in 1603. Ms. Price would have us believe the two events were merely coincidental. That is surely incredible. She asserts that if Robert Cecil and the King considered that Southampton had a claim to the throne as Elizabeth’s heir, they would have left the young Earl in the Tower in 1603 or — Ms. Price shockingly attributing to Cecil and James a capacity for cold-blooded savagery — had him killed. Surely the facts are that James had Oxford’s assurance in 1603 that Southampton would not claim the throne and could be safely freed, but that when Oxford died James feared that with his restraining hand withdrawn, Southampton might indeed make a bid for the throne. In his Shakespeare and the Earl of Southampton, G.P.V. Akrigg writes that “According to the French Ambassador, King James had gone into a complete panic and could not sleep that night even though he had a guard of Scots around his quarters. Presumably to protect his heir he sent orders to Prince Henry that he was not to stir from his chambers.” Southampton was released the next day, no doubt upon his assurance that the King was entirely safe in having him at large.

The only explanation I can find is that, as Elizabeth’s son, Southampton would indeed, certainly in his own view, have had a rightful claim to the Crown, upon which he might be expected to act, while to me this explanation accords with what we may deduce of the relations of Oxford, Elizabeth and Southampton from Shakespeare’s works. I do not know how otherwise the circumstances known to us may be accounted for.

A final point. On the first page of her article, Ms. Price asserts that, were Southampton Oxford’s son, Oxford in promoting his marriage with his daughter Elizabeth would have been encouraging incest unless, as proponents of the theory of the Tudor Rose have to argue, Elizabeth had come into being by Burghley’s having “impregnated his daughter Anne.” Let me refer her to TMWS, pp. 333-34, in which it will be seen that we have no reason at all to believe that Oxford favored a match between Southampton and Elizabeth.

Sincerely,

Charlton Ogburn Beaufort, South Carolina

[highlight][Pp. 9-11 — Diana Price Reply][/highlight]

It is dismaying to find myself in disagreement with a position endorsed by Charlton Ogburn, whose book first interested me in the Shakespeare authorship issue. Yet his defense of the Tudor Rose theory does not squarely confront the factual objections, much less overcome them.

Mr. Ogburn may have “no difficulty in believing that the Queen could have borne a child with only a few persons in on it,” but I do. An unnoticed pregnancy is not only unusual, but for a monarch with relatively little privacy, it is highly unlikely. Mr. Ogburn expressed confidence that “the sealing of gossipy mouths” could be ensured “by the knowledge of what indiscretion could cost” (a suggestion, by the way, that hints at the same sort of “cold-blooded savagery” that Mr. Ogburn found so outrageous in my estimation of the Machiavellian Robert Cecil). A recurring topic of court gossip, both in England and on the continent, was speculation on Elizabeth’s supposed pregnancies and illegitimate offspring. As far as we know, such gossip was without foundation, yet we are to believe that when there was some foundation, all the gossips suddenly went mum.

Who were all these potential gossips? Proponents of the theory have yet to comb the historical archives to catalogue Elizabeth’s activities and personal interactions during the last half of her alleged pregnancy. What evidence shows that access to Elizabeth was restricted to those few who were “in the know”? Were documented personal interactions with non-insiders, such as the French ambassador and low-level courtiers, such as one of the Talbot boys, fabricated? If not, how was concealment possible in each circumstance? How can the Tudor Rose theory have any credibility when the critical assumptions on which it rests are based on mis-used secondhand evidence and an absence of primary research?

Mr. Ogburn claims that I focused “on subordinate issues while the central considerations are overlooked” until the end of the article. Is Mr. Ogburn seriously suggesting that the alleged royal birth of Southampton is a subordinate issue? Surely it is the central consideration. Mr. Ogburn argues that Elizabeth could have concealed her pregnancy — even in the presence of the French ambassador and minor courtiers — by wearing a dress designed for that purpose. Not only is the supposition questionable, it leaves many other objections unanswered. Mr. Ogburn speculates on Elizabeth’s maternity disguise, yet he has himself been justifiably critical of reliance on conjecture when no facts exist, or worse, when known facts refute the case as argued. Similarly, his interpretation of the events of June 24, 1604 remains mere speculation.

With respect to the de Vere-Southampton betrothal, Mr. Ogburn points out that he is on record as having no reason “to believe that Oxford favored a match between Southampton and Elizabeth.” But the chief promoter of the Tudor Rose theory believes otherwise. Mrs. Sears wrote that “Oxford would have realized at this point that a marriage to William Cecil’s daughter/granddaughter would strengthen Southampton’s position as heir to the throne …. Oxford must have regarded this marriage as a guarantee of Southampton’s future inheritance of the Crown” (50).

Mr. Ogburn asks how I would explain the poet’ s address to the Fair Youth of the Sonnets, but he limits my choices to two. Either the Fair Youth was the poet’s gay lover, or he was Oxford’s son by the Queen. Mr. Ogburn’s proposal strikes me as an example of the false dichotomy, a logical fallacy by which various legitimate possibilities in the spectrum are eliminated from consideration. And if a few historical facts render Mr. Ogburn preferred option untenable, then is he not obliged either to modify his hypothesis or to discard it in favor of another?

Mr. Ogburn began by stating that he reluctantly accepted the Tudor Rose theory because he “had no choice.” No other explanations or interpretations would serve. Scholars have struggled for years to squeeze convincing interpretations out of the Sonnets, but those who have proposed unifying theories necessarily begin to speculate where the biographical records leave off. It may be that many more facts about the man who wrote the Sonnets will need to come to light before any interpretation can be proposed with confidence.

[highlight][Pp. 11-15 — from Elizabeth Sears, Somerville, Massachusetts][/highlight]

To the Editor:

All Oxfordians were originally Stratfordians. It was only the recognition of one or more non sequiturs in the Shakespeare story of authorship that caused us to search for an alternative author. Our questioning attitude, however, cannot be handily dropped when we study the life and works from the Oxfordian viewpoint and we are not serving the cause of Edward de Vere when we allow preconceived beliefs to interfere with examining new discoveries and new ideas. We do not have to recant our ideas of the universe like Galileo, nor will we be burned at the stake like Giordano Bruno who refused to recant. Having progressed beyond this kind of censorship, are we not free to report what we have found and believe to be true? There is one fact that must be looked at honestly and fairly. While other members of the nobility and gentry were published posthumously, Oxford was not. His records were destroyed and there has been an obvious cover-up for four hundred years. He states clearly that he was “Tongue Tied by authority” (Sonnet 66). This silence should be recognized as a non sequitur and dealt with accordingly.

Primary sources are admittedly important, but for the reign of Elizabeth I, there is a decided paucity of information. There was little that escaped William Cecil’s censorship. While it was customary for the “pipe roll” records for any given year of a sovereign’s reign to fill three large rooms, it is significant that in one year of the Regnum Cecileanum there were only nine pipe rolls; barely enough to fill a corner of one small room. This was not pruning of excess information, but a great lopping off, a comprehensive censorship.

Therefore, while primary sources are not always available, there were many veiled clues by writers using allegory and painters using Renaissance impresa or portrait devices to convey messages that could not be expressed otherwise. There was a British Secrets Act and a statute forbidding portrayal of high officials on stage. Allegory was used by most writers in Elizabethan times and it is naive to read Shakespeare, or anyone else in the Elizabethan era, in any way other than with double meanings. Oxford, with his ability to think and write in several languages at once, was the supreme master of double entendre and multiple meanings. To see him as less resourceful is to deny him one facet of his genius.

Ms. Price cites in her article, “A Fresh Look at the Tudor Rose Theory,” Charlotte Stopes’ footnote on page 2 of Chapter one of her Southampton biography:

It has always been said he (Southampton) was “the second son,” but there is no authority for that. The error must have begun in confusing the second with the first Henry (i.e., 2nd earl).

The second sentence above was not cited by Ms. Price, nor does she quote an important item from Mrs. Stopes’s preface that might be relevant to Oxfordian research.

From a plain statement of facts, however, we may sometimes secure legitimate inferences.

While the second part of the footnote quoted above seems to be one of those “inferences,” it may be wrong in this case. In the small community that Titchfield was in the 16th Century, the word would have spread freely from the manor to the town that there had been two sons in the family with an unexplained disappearance of the first. Although there was no record of the burial of the first and no record of the birth of the second boy, such things would have been common gossip in the local pub.

Mrs. Stopes was somewhat handicapped by not having access to letters and papers that were still in private hands when she was researching Southampton. Among these were the Losely Letters which were turned over to the Castle Hill Museum in Guildford after World War II and later bought by the Folger Library. Unfortunately, these letters have been edited and omit what might have been crucial evidence. One of these, a letter from the Second Earl of Southampton to Sir William More of Losely, announcing the birth of a boy on October 6,1573, has a blank section where the child’s name might have been given. (Was this deliberately excised, a possible non sequitur?)

However, the Second Earl of Southampton’s original will was surprisingly available for my personal examination at the Ancient Records Office in Winchester, to which Mrs. Stopes did not seem to have had access.

Two important items were added to the Earl’s will after the main portion had been drawn up so self-servingly by his Gentleman of the Bedchamber, Thomas Dymocke. Dymocke had been trained at the Inns of Court, and was descended from a long line of Sovereign’s Champions, at least as far back as Richard II. His uncle, Sir Edward Dymocke, had been Elizabeth’s Ceremonial Champion at her Coronation. Thomas, who would eventually inherit the Barony, was acting as a servant (a non sequitur?). Ostensibly, there was not only a rift (Dymocke-made) between the Earl and his Countess Mary, but also a split with his in-laws. Lord and Lady Montague. Curiously, the first codicil added to the will was a gift to Lord Montague, “in token of perfect love and charitie betweene us” (non sequitur?).

The second addition provided for the education, until the age of twenty-one, of “William, my beggar boye.” For this there may be an explanation. If the boy, born on October 6th, 1573, was named for the Earl’s devoted, Sir William More, who for many months had acted as the Earl’s guardian/ warder when the Earl was first released from the Tower, this clause would have been added to ensure that his own ousted child would be saved from ignorance and desperate poverty. To quote Mrs. Stopes, “From a plain statement of facts, however, we may sometimes secure legitimate inferences.” More non sequiturs in relation to these facts may lend them more weight!

If we return to Mrs. Stopes’ book, we can find on page 9 more material of interest which she does not recognize as odd. She quotes a letter from the then widowed Countess of Southampton.

… Mr. Dymocke voyde of either wytte, abelity, or honesty to dischardg the same (i.e., the will) doth so vexe me as in troth my Lord I am not able to expresse. How to better yt I know no menes to her Majestie but by your menes to her to have consideracion of the man, and great matters that resteth in his hands unaccomptable but by Her prerogative, which I trust by your Lordship’s menes to procure for the good of the child. (Italics added)

Dymocke has been given charge of “great matters” for the Queen (while ostensibly acting as a servant. Non sequitur!). On page 12, another letter from the Countess to Leicester speaks in the same vein of “the child” as opposed to “my child” or “my son.”

Yf possibly yt may be, which truly my Lord can never be (without great hinderance to the child) except such travell (i.e., travail) and paynes which may ever be taken for yt, as I know none can or will do, but he who is tyed to the child both in natur and kynship. That your Lordship shall judge my Lord, my father his meaning or myne, is not to make an undutyfull motion to her Majestie or her state.

The Countess speaks of “the child,” refers to “yt,” “great matters” and her duty to the Queen. (Non sequiturs?).

Ben Jonson speaks of matters in “High Places” in Bartholmew Fair, a play written in 1596, but never performed until 1614. (A non sequitur?) Act I, scene vi:

Zeal-of-the-land-Busy: … Now pig is a meat, and meat that is nourishing, and may be longed for, and so consequently eaten; it may be eaten: very exceeding well eaten. But in the Fair, and as a Bartho’mew-pig it cannot be eaten, for the very calling it a Bartho’mew pig it cannot be eaten, it cannot be eaten, for the very calling it a BarthoV mew pig and to eat it so, is a spice of idolatry, and you make the Fair no better than one of the high places. This I take it is the state of the question. A High place. (Italics added)

In Henry IV 2, II.iv.250, Doll Tearsheet addresses Falstaff as “Thou whoreson little tidy Bartholmew Boar pig” and “Idolatry” has echoes of Sonnet 105.

Let not my love be call’d idolatrie

Nor my beloved an Idoll show

Since all alike my songs and praises be

To one, of one, still such, and ever so.

Kinde is my love today, tomorrow kinde

Still constant in a wondrous excellence,

Therefore my verse to constancie confin’d

One thing expressing, leaves out difference.

Faire, Kinde, and true, is all my argument.

Faire, Kinde, and true, varying to other words,

And in this change is my invention spent.

Three theams in one, which wondrous scope affords.

Faire, Kinde, and true, have often liv’d alone.

Which three till now, never kept seate in one.

The word “kind” has several meanings. Kind is German for child; it also has a now-obsolete usage meaning “sprung” or “begotten.” Kine is an old word for “cattle” and in the cattle family is “Ox.” One may claim this is far fetched, but the Renaissance mind worked this way. Hamlet says of Claudius: “A little less than kind and more than kin.

… Shakespeare was not the only poet who dedicated works to Southampton. Thomas Nashe wrote the following for his Choice of Valentines, which was found in an unpublished manuscript.

A prelude upon the name of

Henry Wriothesley Earl of

Southampton

Ever

Whoso beholds this leafe, therein shall reade

A faithful subjects name, he shall indeede

The grey-eyde morne in noontide clowdes may steep

But traytor and his name shall never meete.

Never.

… Oxford repeatedly expresses his pride in Southampton as the heir to the Crown. The Sonnets title page shows a device, or impresa, of a child wearing the Prince of Wales plumes at the top center. At the bottom are two hares (heirs). Above the first Sonnet is another heading with an impresa of two birds at the top, left and right (Phoenix and Turtle Dove) with an urn in the center. And finally, the portrait of the Earl of Southampton in the Tower is teeming with impresa, which would require a complete paper by itself.

Unlike Stratfordians, Oxfordians have a wealth of material to research. We must take advantage of our authorial view to search with open minds, no matter where it leads us. There must have been important reasons to hide the true authorship for four hundred years. Had it been a matter of “convention,” Oxford’s works would have been published under his own name posthumously. There had to be a serious reason to hide him behind a pen name. Along with the obvious non sequitur of his not being given recognition, there is also the change in his combined Crown and coronet signature after Queen Elizabeth’s death. The entire signature pictures a crown, the top part includes the coronet and Oxford is making a visual double entendre. The signature is really a Renaissance impresa. Obviously, it was critically important for him to discontinue its use after the Queen died, which is definitely another non sequitur.

Two final points: one is that on page 8 of Ms. Price’s article, she mentions that “the death of Charles IX threw Anglo-French relations into fresh confusion. His death destabilized the marriage negotiations with the Duc D’Alençon…” Actually, she had been negotiating with the Duc D’Anjou, who, by the death of his brother, had become King of France (Henri III). Elizabeth could no longer play the game with Anjou and really was in a dilemma. The Duc D’Alençon was only 16 years old and it looked a little foolish to pursue him as a consort, but as there was no alternative, she finally did renew the French negotiations with a boy who was almost young enough to be her grandson. Of course, it was only a political ploy, but it worked for quite a few years, until Elizabeth was 54 and Alençon was dead. Courtships of Queen Elizabeth, by Martin Hume (MacMillan, NY 1896).

The other point is in reference to the interpretation of the Peyton report; it did indeed refer to Oxford, but Ms. Price skirts the issue it presents. It opens up a can of “Verma” that might lead to a revelation re “Ver sacrum.”

Sincerely,

Elizabeth Sears Somerville, Massachusetts

[highlight][Pp. 15-17 — Diana Price Reply][/highlight]

The debate over the Tudor Rose theory seems to be as much about critical thinking as it is about the lineage of Henry Wriothesley. Proponents of the theory have relied almost exclusively on literary interpretations, rather than hard facts, to build their case. One of my objectives in writing the article was to show that the theory had never been properly vetted against the existing historical documentation, even though it had gained uncritical acceptance in certain circles. I attempted to do a small portion of the vetting, and the evidence that I found, in my view, disproved the case as argued in Elisabeth Sears’s Shakespeare and the Tudor Rose.

Mrs. Sears has now submitted her response, but nowhere has she confronted the challenges to the fundamental assumptions on which she based her case. Her theory hinges on the hypothesis that Queen Elizabeth had a baby in May/June 1574. But historical evidence shows that Elizabeth had no opportunity to carry or deliver the baby. I believe I also showed that related assumptions, e.g., that Oxford viewed himself as the royal consort; that there was a second Southampton son; or that Southampton was viewed as a threat to James I, were based on misreadings or inadequate evidence. Surely the burden is now on proponents of the theory to show why the evidence I presented is inadequate to support my conclusions, or to introduce new facts in support of their hypothesis that can be reconciled against the contradictory evidence.

Unfortunately, Mrs. Sears has ignored the factual impediments and reiterated her interpretations of the Shakespeare canon and a few documents, all of which are subject to other interpretations. Mrs. Sears might pile hundreds more pages of interpretations onto her theory, but if the underlying assumptions are proven to be factually untenable, no amount of literary interpretations or conjecture will make them tenable.

My article was critical of inaccuracies, misquotations, and lack of primary research in Shakespeare and the Tudor Rose. More such errors and gaps are found in Mrs. Sears’s response. Some errors appear to be merely careless. For example, she misquotes her own book (56), confusing Thomas Powell’s published dedication to Southampton for A Welch Bayte to Spare Provender of 1603, with Nashe’s unpublished dedication to “Lord S” for Choise of Valentines. She misquotes a line from Hamlet (I.ii.65). In a final point, she writes that it was only when Charles IX died that d’ Alençon was introduced as an alternative marriage candidate. Relying on historian Martin Hume, Mrs. Sears wrote, “Actually she had been negotiating with the Duc D’Anjou.” But the negotiations with D’Anjou gave way to negotiations with d’ Alençon over a year before Charles IX died. Fenelon “broached the subject” in March 1573. The following September, d’Alençon wrote to apologize to Elizabeth for missing their intended rendezvous at Dover; he also sent her a ring as a “love token” (Hume, 170-5).

Other errors show an absence of basic research. For example, Mrs. Sears cited the printer’s ornamentation appearing on two pages of Shake-speares Sonnets. According to Mrs. Sears, Oxford:

repeatedly expresses his pride in Southampton as the heir to the Crown. The Sonnets title page shows a device, or impresa, of a child wearing the Prince of Wales plumes at the top center. At the bottom are two hares (heirs). Above the first Sonnet is another heading with an impresa of two birds at the top, left and right (Phoenix and Turtle Dove) with an urn in the center.

Mrs. Sears is pointing to the ornaments in the 1609 edition of Shake-speares Sonnets as iconography using Tudor Rose motifs. This is interpretative nonsense.

If Mrs. Sears is suggesting that the edition was designed with a wink at Southampton’s royal lineage, how does she explain the presence of the same artwork on any number of other books published before and after 1609? The ornament with the hares appears on the title pages for A Mad World My Masters (1608), The Merry Devils of Edmonton (1608), and in Jonson’s 1616 Workes over the title Catiline. The second ornament featuring the two birds appears in George Chapman’s An humorous days mirth (1599) and The Gentleman Usher (1606), and in Histrio-Mastix (1610), among others. Obviously, these ornaments were the printers’ clip-art, pulled from regular stock. Yet Mrs. Sears interprets them as specifically symbolic of the Tudor Rose themes that she finds in Shake-speares Sonnets. It is difficult to escape the inference that Mrs. Sears is prone to reading meaning into anything supporting her theory, while avoiding the critical analysis that might compromise such “evidence.”

The errors in both Mrs. Sears’s book and rebuttal cannot inspire confidence, but they pale beside her fundamental error of ignoring the historical evidence that disproves her hypothesis. Chauncey Sanders, the author of An Introduction to Research in English Literary History (Macmillan, 1952) offered sobering advice to any student who proposes a new interpretation to a work of literature (228-9):

Let him amass all the evidence he can find. Let him set down, in orderly fashion, all the arguments in favor of his interpretation, and then, with equal or greater scrupulousness, all those against. Let him study the evidence, giving full value to every argument; for it may very well happen that a single bit of contra evidence will make the piling up of pro arguments like the adding together of zeros: whether there are twelve or twenty, the total is still zero. Having assured himself that he has a case, let the student then present his hypothesis, not as a revolutionary discovery that must supplant the quaint notions of his predecessors, but as a tentative suggestion for the consideration of those who may be able to bring further evidence to bear on the matter.

The founders of the Shakespeare Fellowship, among them Sir George Greenwood and J. Thomas Looney, clearly respected the critical method. In their 1922 statement of purpose, they expressed a “desire to see the principles of scientific historical criticism applied to the problem of Shakespearean authorship.” It does seem that Mrs. Sears and her followers have gone off in the opposite direction.

A scientific method requires us to revise or discard a hypothesis when it is contradicted by documentary evidence, no matter how abundantly the theory may appear to be corroborated by literary interpretations. If proponents of the Tudor Rose theory do not accept that basic tenet of critical thinking, it is probably pointless for those who are skeptical to argue further.

Membership dues cover only a fraction of our budget, including all our research, preservation and programming. Please support the SOF by making a gift today!

Blue Boar Tavern: Wassail Q&A

Tuesday Dec. 17, 8pm E / 5pm P

Sign up below for event invites!