Eliot Slater

Editor’s Note: In 1969 Eliot Slater published a substantial article on the Shakespeare Authorship Question in the journal of psychiatry Anais Portugueses de Psiquiatria. The first half of the article is available on the website http://eliotslater.org. The second half of the article, in which Slater focuses on the Sonnets and in particular what he—as an eminent psychiatrist—sees in them, has never been reprinted. The text below picks up where Slater is summarizing the reasons why he finds the Stratfordian position unconvincing.

[…]

The Stratfordian case has persisted largely by default, just because it is so generally adhered to. It has not been my purpose to prove that William of Stratford did not write the works of Shakespeare but merely to show that it is possible that he did not—that there are rational grounds for doubt—and above all, that in view of the arguments that can be raised on both sides, the only appropriate attitude is an open-minded one. If we wish, as we should, to make a scientific approach to the range of problems with which Shakespeare and his works confront us, we must not assume a certainty of the authorship as our basic premise. This is a question that has to be solved by research, not first answered by an act of faith and then used as an axiom to guide or to misguide.

[pullquote]In the discussion that now follows I wish to make no identification at all, but to see where we are led if we approach the 155 Sonnets without any preconceptions at all.[/pullquote] In scientific work, hypotheses are valued according to their heuristic potentialities. The Stratfordian hypothesis has been very fully exploited; it has led to solutions of some questions of a varying degree of satisfactoriness, and it has proved incapable of providing any acceptable solution of some other questions. In contrast, the hypothesis that Shakespeare was not William of Stratford, but an unknown to be identified, has received hardly any attention. The proponents of non-Stratfordian hypotheses practically always start with another identification as a basic premise, and then see how well the facts can be fitted, though it is true that J. Thomas Looney began his work on the basis of an unknown anonymous author, and then proceeded by literary detective work to identify the unknown with Edward de Vere.

In the discussion that now follows I wish to make no identification at all—not even to exclude William of Stratford—but to see where we are led if we approach the 155 Sonnets without any preconceptions at all.

The Poet’s Age

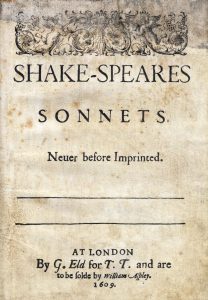

Shake-speare’s Sonnets were first published in 1609, but modern authorities are agreed they were written very much earlier. They are mentioned as having been in circulation in a pamphlet published in 1598 and two of them were published in 1599 in an anthology of mixed authorship. Most scholars think the sonnets were started in 1593-4 and they connect the earlier ones with Venus and Adonis (published 1593) and The Rape of Lucrece (published 1594). Again, most scholars think they continued to be written until 1603, since sonnet 107 is thought to refer to the death of Queen Elizabeth, the accession of King James, and the release of the Earl of Southampton from the Tower of London; all these events occurred in that year in quick succession. The Earl of Southampton was the subject of the dedications by Shakespeare of both poems. The dedication of Lucrece is in warm, intimate terms, breathing a devotion which the poet seems to feel sure is acceptable and accepted.1

It seems therefore probable, if not certain, that the aristocratic and beautiful young man to whom the sonnets are addressed was this same young nobleman who fits the empty place in the jigsaw very well. Nevertheless, there are other possibilities and Dover Wilson prefers another still younger man, William Herbert, Earl of Pembroke.

There are in all 154 sonnets. The first 126 are addressed to this youth, whoever he may have been, the remainder being a rather miscellaneous group of doubtful dating, of which the most interesting are those concerned with or addressed to the “Dark Lady of the Sonnets.” The first 17 sonnets urge the young man to marry in order that he may immortalize himself in his posterity. In 1590 the Earl of Southampton was aged 17 and from 1590 to 1594 negotiations were going on, though ultimately to break down, to make a match between him and Elizabeth, the daughter of Edward de Vere, 17th Earl of Oxford (1550-1604) whom some believe to have been Shakespeare. After sonnet 17 these appeals cease, but the sonnets continue, now in terms of increasing tenderness and devotion—“affectionate admiration—perhaps adoration at times would not be too strong a term—of a man of mature years for another man much younger than himself, in this case perhaps fifteen to seventeen years younger.”2 It may be that this is an underestimate of the difference which could be, say, twenty-three years.

Sonnet 2 begins:

When forty winters shall besiege thy brow

And dig deep trenches in thy beauty’s field,

Thy youth’s proud livery so gazed on now,

Will be a tattered weed of small worth held

The first thy carries a stress that draws the contrast between the speaker and the youth. The time will come when the latter too, will be over the age of forty, with wrinkled forehead and “deep sunken eyes” (line 7). The same gap of a generation is implied less directly in sonnet 3:

Thou art thy mother’s glass and she in thee

Calls back the lovely April of her prime

which tells us that Southampton’s mother was a beauty in days of youth when Shake-speare knew her. In sonnet 22, we read:

My glass shall not persuade me I am old,

So long as youth and thou are of one date,

But when in thee time’s furrows I behold,

Then look I death my days should expiate.

That is, it will be time in every sense for me to die, when you are as old as I am now—and I am, say sixty? Similarly sonnet 37 (“As a decrepit father takes delight, / To see his active child do deeds of youth”) implies a difference in ages of not less than twenty years. In sonnet 62 the poet bitterly reproaches himself for self-love, even love of his own person, until the moment:

But when my glass shows me myself indeed,

Beated and chopped with tanned antiquity.

Everyone who believes the speaker was William of Stratford who at the time, say 1596 or so, would have been about 32 years old, exclaims against this ludicrous self-description. Even for a man in his mid-forties it would seem to be excessive, but not so if he were either depressed or physically ill, a possibility which is discussed later. The theme is developed at length in sonnet 63:

Against my love shall be as I am now

With Time’s injurious hand crushed and o’erworn,

When hours have drained his blood and filled his brow

With lines and wrinkles, when his youthful morn

Hath travelled on to age’s steepy night,

And all those beauties wherof now he’s king

Are vanishing, or vanished out of sight,

Stealing away the treasure of his spring:

Once more we see the contrast between the Poet and his beloved: “as I am now… When hours have drained his blood.” Finally we have a wonderful description of the age of involution as seen from within in sonnet 73:

That time of year thou mayst in me behold,

When yellow leaves, or none, or few do hang

Upon those boughs which shake against cold,

Bare ruined choirs, where late the sweet birds sang.

In me thou seest the twilight of such day,

As after sunset fadeth in the west,

Which by and by black night doth take away,

Death’s second self that seals up all in rest.

In me thou seest the glowing of such fire,

That on the ashes of his youth doth lie,

As the death-bed, whereon it must expire,

Consumed with that which it was nourished by.

_____This thou perceiv’st, which makes thy love more strong

_____To love that well, which thou must leave ere long.

The picture is of intense depression, and carries a strong hint of bodily illness and death not far away.

It is very relevant to a consideration of the probable age of the Poet that he is so much with death and with the ineluctable passage of time. The ravages of Time are a main theme of sonnets 1, 2, 3, 5, 7, 11, 12, 15, 16, 17, 18, 19, 22, 30, 33, 55, 60, 63, 64, 65, 77, 104, 107, 123, 126, and 146. In sonnets 12, 15, 19, 55, 60, 63, 64, 65 and 77 the theme dominates the sonnet completely and is very powerfully expressed. In sonnet 12:

When I do count the clock that tells the time,

And see the brave day sunk in hideous night,

When I behold the violet past prime,

And sable curls all silvered o’er with white:

When lofty trees I see barren of leaves,

Which erst from heat did canopy the herd

And summer’s green all girded up in sheaves

Borne on the bier with white and bristly beard:

Then of thy beauty do I question make

That thou among the wastes of time must go

Against this terrible deity, the Poet lifts up, as a shield over the head of the beloved youth, a tremendous incantation in sonnet 55:

Not marble, nor the gilded monuments

Of princes shall outlive this powerful rhyme,

But you shall shine more bright…

‘Gainst death, and all-oblivious enmity

Shall you pace forth, your praise shall still find room,

Even in the eyes of all posterity

That wear this world out to the ending doom.3

Nevertheless Time remains, from start to finish of the sonnet sequence, the inveterate enemy with whom no reconciliation is possible: Wasteful Time, this bloody tyrant Time, devouring Time, swift-footed Time, Time’s injurious hand, Time’s fell hand, Time’s thievish progress to eternity, Time’s spoils, Time’s hate, the fools of Time, Time’s fickle glass. From sonnet 1 to 126, Time figures 51 times in 33 sonnets. But the poet achieves no equanimity, no philosophical acceptance of the inevitable. Time is opposed again and again to Love, but after all vicissitudes, in the end there is only such despair as speaks in the heart-rending answer of sonnet 64:

When I have seen such interchange of state,

Or state itself confounded to decay,

Ruin hath taught me thus to ruminate

That Time will come and take my love away.

This thought is as a death which cannot choose

But weep to have, that which it fears to lose.

Considering the progress of Time, the Poet finds himself looking ever and again in the face of death. Death, deaths, dead, die, dies, diest, dying, died come 53 times in 41 sonnets and receive the stress and prominence of rhyming syllables 16 times. In addition are many synonyms: perish, end, decease, expire, mortality, and many references to graves, tombs, monuments, and sepulchers. No better than to Time can the poet reconcile himself to Death, least of all to the death of his beloved, but not even to his own death though he feels it as the end to mortal sickness: “To be death’s conquest and make worms thine heir,” “And barren rage of death’s eternal cold,” “When that churl death my bones with dust shall cover.” The death theme is dealt with at full length in sonnets 71 to 74 and again in sonnet 81—death with all its panoply of worms and corruption.

Rendall, in Shakespeare’s Sonnets and Edward de Vere, has pointed out that Shakespeare nowhere hints at any belief in life after death, and that in the Sonnets the only hope of immortality he expresses is that his verse shall live to enshrine the name of his beloved (who is nowhere mentioned by name). He seems to believe that even these sonnets will not immortalize his own name, and writes as if his authorship was covered by anonymity:

My name be buried where my body is. (72)

Why write I still all one, ever the same,

And keep invention in a noted weed,

That every word doth almost tell my name. (76)

Though I (once gone) to all world must die,

The earth can yield me but a common grave…

Your monument shall be my gentle verse…

You still shall live, (such virtue hath my pen)

Where breath most breathes, even in the mouths of men. (81)

I’ll live in this poor rhyme. (103)

The Poet’s Melancholia

Shakespeare’s preoccupation with his own aging, a physical decay destined to end in death, gives by itself an impression of such melancholy that we are bound to consider whether he may have had a depressive illness. Scholars have repeatedly emphasized the world-weariness, the despair of human kind and the self-contempt that inspire so much of the poetry and the action of such plays as Hamlet, King Lear, and Timon of Athens; and some (Chambers, for instance) think of the possibility of a nervous breakdown. The Sonnets are a record which can help us to a partial answer of whether the Poet was ever in worse case than merely very miserable, or whether, in fact, he had a mental illness.

The illness that comes in question is an endogenous depression,4 and there is much to suggest that it did actually occur. During the course of the sonnets we see signs, first of its appearance from nowhere, then a progressive worsening to a state that is unmistakably morbid, and then its gradual passing off in a grumbling diminuendo. As is the way with an endogenous depression, when it is at its worst, psychic powers are slowed down, perhaps to a halt. Sonnets 85, 86, 100, and 101 suggest invention completely dried up for a time; in sonnets 76, 103, and 105 the Poet complains of its sameness and monotony.

All is well until sonnet 27. In sonnet 26, Shakespeare has made a formal acknowledgement of his beloved’s suzerainty as in feudal days of yore:

Lord of my love, to whom in vassalage

Thy merit hath my duty strongly knit;

To thee I send this written embassage

To witness duty, not to show my wit.

In the next sonnet, abruptly, and for the first time, we are told of an intractable insomnia, very commonly the first symptom of an involutional depression.5 The insomnia persists, and comes out again even more strongly in sonnet 28:

How can I then return in happy plight

That am debarred the benefit of rest?

When day’s oppression is not eased by night,

But day by night and night by day oppressed,

And each (though enemies to either’s reign)

Do in consent shake hands to torture me.

In the next sonnet, 29, with equal abruptness, the note of a bitter self-reproach is struck for the first time, to recur later again and again:

When in disgrace with Fortune and men’s eyes,

I all alone beweep my outcast state,

And trouble deaf heaven with my bootless cries,

And look upon my self and curse my fate…

…in these thoughts my self almost despising.

Depiction of depression of the involutional type continues in sonnets 33, 34, 36 (“my bewailed guilt”), 37, 43 (insomnia again), and in 44, 45, 49, 50, 61, 62, 66, 71, 72 and 74.

In sonnet 45 two elements, “Slight air and purging fire,” have left him, and “My life, being made of four, with two alone / Sinks down to death, oppressed with melancholy.” In sonnet 49, he looks forward to the time when “thou shalt strangely pass, / And scarcely greet me with that sun, thine eye.” Sonnet 50 gives almost a classic account of that feeling of heaviness, like a cold weight in the chest, which we know as one of Schneider’s first-rank symptoms of depression. The poet on a journey, away from his beloved, is one with his horse, each carrying a dead weight (“The beast that bears me, tired with my woe, / Plods dully on, to bear that weight in me”). In sonnet 61 comes more insomnia, and in the night the thought of “shames and idle hours.” More self-reproach is the theme of sonnet 62:

Sin of self-love possesseth all mine eye,

And all my soul, and all my every part;

And for this Sin there is no remedy,

It is so grounded inward in my heart.

Sonnet 66 begins “Tired with all these for restful death I cry,” and follows with a list of human follies and villainies which bear a strong resemblance to the list in Hamlet’s soliloquy (Hamlet, 3, 1). In sonnet 71 we reach at last the nadir, the pit of despair, with a total self-abnegation which would yet seek to spare the beloved some pain:

No longer mourn for me when I am dead,

Than you shall hear the surly sullen bell

Give warning to the world that I am fled

From this vile world with vilest worms to dwell:

Nay if you read this line, remember not

The hand that writ it, for I love you so,

That I in your sweet thoughts would be forgot,

If thinking on me then should make you woe.

O if (I say) you look upon this verse,

When I (perhaps) compounded am with clay,

Do not so much as my poor name rehearse;

But let your love even with my life decay.

Lest the wise world should look into your moan,

And mock you with me after I am gone.

Sonnet 72 continues the same theme; his friend must forget him when he is gone: “After my death (dear love) forget me quite, / For you in me can nothing worthy prove…My name be buried where my body is, / And live no more to shame nor me, nor you.” In sonnet 74 again he is “Too base of thee to be remembered.”

After this, the depth of the depression lessens, but it comes back and back in later sonnets to interrupt or to tinge reflections of another kind with an inky hue in sonnets 76, 79 (“my sick muse”), 81, 89, 90, 92, 93, 95, 110, 111, 112, 119. In the last of these the Dark Lady has entered on the scene, to bring the poet tortures of another kind.

However, before the depressive mood has petered out it has provoked some exhibitions of a paranoid tendency. He suspects his friend of hating him and wishing him ill, even as the world itself has had a spite against him:

Then hate me when thou wilt, if ever, now,

Now while the world is bent my deeds to cross,

Join with the spite of fortune, make me bow,

And do not drop in for an after-loss. (90)

This is the first of four sonnets handling the same theme. Sonnet 91 imagines his friend deserting him completely; sonnet 92 begins by defying him to “do thy worst thyself to steal thyself away,” and ends “Thou mayst be false, and yet I know it not.” Sonnet 93 continues with “So shall I live, supposing thou art true, / Like a deceived husband,” and with imaginings of the evil thoughts, the false heart behind the face of sweet love. This suspicion, morbid one would think, leads directly into an outright attack on the friend, which comes up for discussion in the next section.

In Summary, the Sonnets provide very suggestive evidence that during the time they were being written Shakespeare passed through a severe but temporary depression. After the worst of the storm was over, a melancholic groundswell persisted for some time. But temporary the depressive illness must have been. The later sonnets show an improved mental state and reconciliation to his friend and to his fate. We can be sure, despite uncertainties of dating, that energetic play-production continued after Troilus and Lear and Timon, with the equable and serene Tempest as the last play of all.

The Poet’s Homosexuality

Most lovers of Shakespeare, particularly the orthodox scholars of an earlier academic generation, are so affronted by the suggestion that Shakespeare was “homosexual” that they reject it out of hand and do not stop to consider just what is implied. The hypothesis that is advanced here is not one to impute moral infamy of even the slightest degree, but it is one which should be of great help in understanding Shakespeare’s attitude to sexuality. The hypothesis can be based solely on the evidence of the Sonnets, which permits us to use the plays as an independent check. The hypothesis proposed is that Shakespeare had a basically homosexual (or perhaps better “homoerotic”) orientation, which laid him open to a passionate and romantic attachment to one of his own sex and made it impossible for him to develop a normally tender, protective, and fully erotic love for a woman. While it is suggested that Shakespeare was “in love” with the young man he addresses in the Sonnets, it is not suggested that the love relationship ever took on an overtly sexual character. Let us first examine the evidence for the negative part of this formulation.

Sonnets 1-126 cover several years (at least three)6 and show a series of stages of development. After the initial courtly overtures and an increasing attachment, there came periods of separation, periods of regular, perhaps daily contact,7 estrangement and reconciliation. It is almost unthinkable that if the relationship between the two men had had an overtly sexual aspect, there should have been no echo of it in the poems of love and adoration that poured out in such profusion. Love-making of its essence involves bodily contact; and those who love one another, and who have made love, are bound in times of absence or frustration to call to mind the solace that such bodily contacts provided. In all his sonnets to his friend, Shakespeare never makes mention of a bodily touch. There is no word about the soft texture of skin, the resilience of muscles, the suppleness of limbs, the firmness of an embrace—in fact no imagery at all drawn from tactile, hot and cold, deep pressure and kinaesthetic senses.8 In fact, one can be nearly certain, not only that physical love-making never took place between the two friends, but that the imagining of such a physical relationship played no significant part in the Poet’s emotional enslavement.

That being granted, we still have to concede that the nature of Shakespeare’s attachment was much more one of love than friendship. Relationships of these two kinds differ not only in the level and intensity but even in the psychic dimension in which they manifest. The love relationship, calling on energies of profounder origin in subcortical centers arising in fact from brain systems involved in sexuality, provides a much more potent and enduring source of driving emotion than any unsexualized feelings of friendship. It was emotions of great depth and power and constancy that drove the Poet on, over the course of years, to produce these sonnets of elation and despair, of self-dedication, self-abasement and self-torture, of violent jealousy and savage reprisal.

Shakespeare’s feeling for the beloved youth is an infatuation—not love in any temperate sense—and, as is the nature of an infatuation in contrast to a love that is returned, it thrived on neglect, humiliation, and equally casual acceptance and rejection.9 Shakespeare’s love has been likened to the love of a doting father, and he does indeed choose for himself the role of ‘father’ in sonnet 37, but also that of ‘husband’ in sonnet 93, to define his attitude, and to the love of Socrates for Alcibiades. But, to the present writer, it calls to mind more readily the infatuation of Oscar Wilde for Lord Alfred Douglas. There is little to show that the mental characteristics of the beloved youth, his wit or wisdom or graces of the mind, or his tenderness or affection played any real part in his allure. To be sure, in sonnet 69 we read of “the beauty of thy mind,” and in sonnet 82 the Poet says “Thou art as fair in knowledge as in hue.” In sonnet 105 he calls him “fair, kind and true,” and begs for a welcome, “even to thy pure and most loving breast” in sonnet 110. But these are quite isolated instances, and apart from them, the talk is all of “bright eyes,” “sweet self,” “your sweet semblance,” “my love’s fair brow,” “thy lovely grace,” “my love’s sweet face,” and in sonnet after sonnet it is the word beauty signifying particularly the beauty of the eyes and face that comes to his mind, as he attempts to pin down, like a captured butterfly, the perfections of his lovely boy. A number of sonnets (18, 20, 24, 53, 54, 99, 104, and 106) are devoted exclusively to hymning the beauty of the youth. Shakespeare, in fact, made for himself an idealized image before which to prostrate himself, and that he could go on loving, even when the real man was treating him with carelessness and, perhaps, cruelty.

The only idea that springs up in the poet’s mind more constantly than this physical beauty is the overmastering obsession of his own love. The statement of this love is at its most powerful when it is least covered in conceits, and is presented naked, in the simplest possible language: “Thou…hast all the all of me” (31), “thou art all the better part of me” (39), “Thou best of dearest, and mine only care” (48), “My spirit is thine, the better part of me” (74), “You are my all the world” (112).

To these many more could be added, but the following must suffice:

Haply I think on thee, and then my state

(Like to the lark at break of day arising

From sullen earth) sings hymns at heaven’s gate.

(Sonnet 29)

Take all my loves, my love, yea take them all,

What hast thou then more than thou hadst before?

No love, my love, that thou mayst true love call

All mine was thine, before thou hadst this more:

(Sonnet 40)

Tired with all these, from these I would be gone,

Save that to die, I leave my love alone.

(Sonnet 66)

No longer mourn for me when I am dead…

Nay if you read this line, remember not

The hand that writ it, for I love you so,

That I in your sweet thoughts would be forgot,

If thinking on me then should make you woe.

(Sonnet 71)

For nothing in this wide universe I call

Save thou my rose, in it thou art my all.

(Sonnet 109)

In sonnet 75, the Poet indicates how his love has become an obsession (“So are you to my thoughts as food to life”). He compares himself to a miser with his wealth:

Now proud as an enjoyer, and anon

Doubting the filching age will steal his treasure,

Now counting best to be with you alone,

Then bettered that the world may see my pleasure,

Sometime all full with feasting on your sight,

And by and by clean starved for a look,

Possessing or pursuing no delight

Save what is had, or must from you be took.

The development of the poet’s passion shows up in the succession of sonnets, as each follows the one before. After the first seventeen beseeching the youth to marry, with their flowery but restrained expressions of admiration, there comes something more fervent in the eighteenth: (“Shall I compare thee to a summer’s day? / Thou art more lovely and more temperate”). Sonnet 20 describes in all detail what gave the youth his magical attractions. This sonnet has been the cornerstone of the arguments for and against an attribution of homosexual inclinations to the Poet, since it allows of two deductions which appear to be in contradiction:

A woman’s face with nature’s own hand painted

Hast thou, the master-mistress of my passion;

A woman’s gentle heart, but not acquainted

With shifting change as is false women’s fashion;

An eye more bright than theirs, less false in rolling,

Gilding the object whereupon it gazeth;

A man in hue, all hues in his controlling,

Which steals men’s eyes and women’s souls amazeth.

And for a woman wert thou first created,

Till nature as she wrought thee fell a-doting,

And by addition me of thee defeated,

By adding one thing to my purpose nothing.

But since she pricked thee out for women’s pleasure,

Mine be thy love and thy love’s use their treasure.

(Sonnet 20)

The double interpretation arises from the double entendre pricked in line 13. This does indeed state quite clearly that when nature made the youth a man, the Poet was ‘defeated,’ that is, prevented from consummating his love. This is in line with the hypothesis proposed earlier, that this love for the beautiful boy was ‘platonic.’ But at the same time the double entendre tells us what kind of love it was that could be so defeated. These were such feelings as might have led—if they had been aroused by a girl—not to ‘defeat’ but to ‘conquest.’ The last four lines define explicitly what is implicit in the rest of the poem, the romantic and erotic tone of the emotional pressures under which the Poet was writing. The boy was an object of sexual love, even if he was a forbidden object. One might go further and say it was the very feature which made him a forbidden object which potentiated his attraction. Though he had all and more of a woman’s charms, he was not a member of that dangerous sex, not one of those “false women.”

From sonnet 20 on, the love story takes an uneventful course for some time. His love is one of few solaces to which recourse is possible when Shakespeare is troubled by insomnia and depression. Then with sonnets 33-35 we hear that the young man has “disgraced” himself, has done a deed of “shame,” by which Shakespeare has been sorely hurt. Sonnets 40-42 make it clear that the offence was in having an affair with Shakespeare’s own mistress. In sonnets 133 and 134, when Shakespeare bitterly reproaches the Dark Lady, we get the other half of the picture. Shakespeare’s attitude to the two unfaithful ones is very partial: the youth is quickly forgiven, but the woman is not. She is condemned outright.

At this point something happens which is very strange indeed. Shakespeare finds some consolation by identifying himself with the other two lovers, to be present as it were, at their lovemaking. This comes out in sonnet 133 and even more so in sonnet 42, below.

But here’s the joy, my friend and I are one;

Sweet flattery! Then she loves but me alone.

Of Sonnet 42, the psychoanalyst Bronson Feldman (1953) has written: “The repressed homosexuality of Shakespeare becomes painfully manifest here. It is obvious that his imagination rioted in fantasies of the woman yielding herself to the man in whom he saw the mirror of his own youth. Unknown to his infinitely clever ego was the fantasy beneath these thoughts, the fantasy of taking the woman’s place.”

If such mechanisms did indeed play a part in Shakespeare’s unconscious, it would help us to understand how he could empathize himself into the personalities of some of the women of his plays. Such fictional women would in any case not have for the hypersensitive homosexual, the terrifying qualities of women of flesh and blood, and would be additionally idealized by being represented on the stage by boys.

In sonnet 42, Shakespeare tells us what it was that wounded him when the third side of the triangle was completed: “That thou hast her it is not all my grief…That she hath thee is of my wailing chief.” This was, to be compelled, by a female, to share the possession of his beloved boy. The whole of Shakespeare’s affections were monopolized by the boy, and he would have wished to monopolize him in turn. The bargain proposed in sonnet 20 (“Mine be thy love and thy love’s use their treasure.”), that the young man was to be allowed his heterosexual liaisons, proves in the end to be beyond Shakespeare’s powers of fulfillment.

After the rather feeble rebukes of sonnets 33 and 34, in the attempt somehow to retain his hold, Shakespeare turns his rage upon himself and ends by groveling in a pit of self-humiliation (sonnets 35, 40, and 42). Such a point is reached in sonnet 57 that Dover Wilson thinks he is speaking ironically, but alas, one fears that Shakespeare did actually reach this abyss:

Being your slave, what should I do but tend

Upon the hours and times of your desire?

I have no precious time at all to spend,

Nor services to do, till you require;

Nor dare I chide the world-without-end hour

Whilst I (my sovereign) watch the clock for you,

Nor think the bitterness of absence sour

When you have bid your servant once adieu.

Nor dare I question with my jealous thought

Where you may be, of your affairs suppose,

But like a sad slave, stay and think of naught,

Save where you are, how happy you make those.

So true a fool is love, that in your will

(Though you do anything) he thinks no ill.

Sonnets 58, 71 (painfully sincere), and 72 (more melancholic than masochistic) continue the theme, to end with the triple gush of sonnets 88, 89, and 90.

After this there is a sudden revulsion, and Shakespeare turns on the friend who has caused him such pain, and rends him. We see his character analyzed in sonnet 94:

They that have power to hurt, and will do none,

That do not do the thing they most do show,

Who moving others are themselves as stone,

Unmoved, cold, and to temptation slow

and his “sins” and “vices” are sternly pointed out in sonnets 95 and 96.

Only after all these storms have passed over is Shakespeare able to settle into the comparatively quiet mood of the later sonnets.

Important evidence bearing on Shakespeare’s homoerotic orientation is to be gathered from his attitude to women. It seems that, while women were to be tolerated as long as they no constituted no threat to him, a desirous, sexually aroused woman was for him an object at once terrifying and disgusting. While he was at times able to observe his own reactions in a tolerant spirit (151), this seems to have been but rarely the case. As a rule, feelings of lust in himself were abominable, and to give way to them was a degradation. The passionate outburst in sonnet 129 (“Th’ expense of spirit in a waste of shame / Is lust in action;”) is too well known to need quotation in full. This cry of self-hatred and self-contempt is (to my knowledge) unique in English literature, and shows a pathological attitude to sex, and an incapacity to reconcile sexual drives with the rest of his nature.

It has been maintained by J. Dover Wilson that Shakespeare only developed an attitude of rejection towards the normal physical relations of the sexes in his later plays.10 But this is a mistaken view. Dislike and disgust for human sexuality are shown from the very beginning. Venus and Adonis11 depicts the queen of love as a ravening bird of prey, and The Rape of Lucrece gives a correspondingly shocked and shocking picture of the lustful male in the role of the ruthless ravisher. One of the earliest plays, The Comedy of Errors, gives an anatomical analysis of the human female which is at once ludicrous and revolting. And another, Love’s Labour’s Lost, presents Berowne (the dramatist’s spokesman) exclaiming against contemptible Dan Cupid, “Dread Prince of Plackets, King of Codpieces,” and angrily resenting his enslavement to:

A whitely wanton with a velvet brow,

With two pitch-balls stuck in her face for eyes,

Ay and, by heaven, one that will do the deed,

Though Argus were her eunuch and her guard!

And I to sigh for her, to watch for her,

To pray for her, go to: it is a plague

That Cupid will impose for my neglect

Of his almighty dreadful little might.

(LLL, 3, 1, 191-198)

No, we must accept the fact that Shakespeare never did have a normal attitude either to women or to sexuality, that his deficiency showed itself from the beginning of his writing life, and that it stayed with him (apart from a few sunnier hours) all through it to the end.

However, he was entrapped into a sexual relationship with a woman, as he states specifically in sonnets 138 and 151. In a more tolerant mood (151), it seems to have been momentarily a source of wonder to him, rather than guilt; one supposes that he had feared he would prove impotent (an anxiety which would have been only too natural in his case) and was correspondingly relieved when the reverse proved true in the event. However, “she who makes me sin, awards me pain” (141), and the magical effect the lady had upon him also caused him to torture himself, to rebel against his infatuation—“thou proud heart’s slave and vassal wretch to be”—and to do all he could to destroy her utterly in his mind and annihilate her attraction.

Psychologically naive commentators have taken Shakespeare’s complaints of his mistress at face value, despite the fact that the charges he brings against her are monstrous and, obviously, inapposite (“the bay where all men ride,” “the wide world’s common place,” sonnet 137, and see also 147 below.) One does not accuse a common prostitute of being a common prostitute, and against anyone else the accusation, though frequently made by enraged lovers, is merely so much abuse intended to relieve the feelings of the one and hurt the feelings of the other. In the same spirit, Shakespeare disparages the lady’s physical charms. The famous sonnet 130, (“My mistress’ eyes are nothing like the sun”) is, to be sure, a skit on the extravagances of other sonneteers, but shows a morbid hostility in the grossness and insult to which it descends (“And in some perfumes is there more delight, / Than in the breath that from my mistress reeks.”) The physical attack on the enchantress is repeated again and again, in the effort, one supposes, to annul her magic:

In faith, I do not love thee with mine eyes,

For they in thee a thousand errors note;

But ’tis my heart that loves what they despise,

Who, in despite of view, is pleased to dote.

Nor are mine ears with thy tongue’s tune delighted;

Nor tender feeling to base touches prone.

Nor taste, nor smell, desire to be invited

To any sensual feast with thee alone:

But my five wits, nor my five senses can

Dissuade one foolish heart from serving thee,

Who leaves unswayed the likeness of a man,

Thy proud heart’s slave and vassal wretch to be:

Only my plague thus far I count my gain,

That she that makes me sin awards me pain.

(Sonnet 141)

The attack on her person is paralleled by the attack on her character: “In nothing art thou black save in thy deeds” (131), “thy cruel eye,” “thy steel bosom” (133), “thou art covetous” (134), “l know she lies” (138), “my female evil,” “her foul pride” (144), “thy foul faults” (148), etc. Not a shadow of a cause is shown why she should be thought so ill of, and what we listen to is the hatred and abuse that is wrung from a self-tortured spirit. The reason for his malignity was not in her, but in him. The extremity in which he found himself provides an amply sufficient explanation:

My love is as a fever longing still,

For that which longer nurseth the disease,

Feeding on that which doth persevere the ill,

The uncertain sickly appetite to please…

Past cure I am, now reason is past cure,

And frantic-mad with evermore unrest,

My thoughts and my discourse as mad as men’s are,

At random from the truth vainly expressed,

For I have sworn thee fair, and thought thee bright,

Who art as black as hell, as dark as night.

(Sonnet 147)

Perhaps the only sonnet which shows the Poet in a mood of some tenderness is 143, in which he imagines himself “thy babe,” and begs her to “play the mother’s part, kiss me, be kind.”

The sonnets to the man and the sonnets to the woman throw light on Shakespeare’s sexual nature from opposite sides, and enable us to see it in depth. Sexuality was the element in his nature with which he was never able to cope successfully. The love he felt for the young man had no conscious sexual component (though a powerfully homoerotic element at an unconscious level), and, despite the suffering it brought him, he felt it to be a healthful, altruistic self-dedication, that ennobled both him and the beloved boy. On the other hand, the enslavement to the sexually active female, which held him for a time, ran, he felt, against the truest inclinations of his nature, and debased both him and her:

Two loves I have of comfort and despair,

Which like two spirits do suggest me still,

The better angel is a man right fair:

The worser spirit a woman coloured ill.

(Sonnet 144)

When one reads in these poems, in which there is so much more of despair than of comfort, of the frantic efforts Shakespeare made to come to terms with his own nature, and somehow or other to achieve a rewarding relationship with the one sex and with the other, one is wrung with pity, not only to see such a great spirit brought to such depths of suffering and humiliation, but to know that his struggles were foredoomed. There was, in fact, nothing to be hoped for from the young man, held off from a loving relationship by his own superficial nature as well as community of sex. Who knows but the woman might have been able to return his love, if only he had been able to give it to her?

(image by Leonid Pasternak)

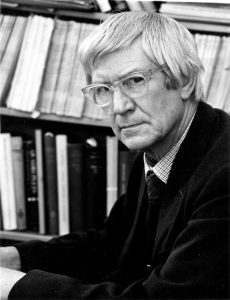

Eliot Slater was a British psychiatrist and a pioneer in the field of the genetics of mental disorders. He held senior posts at the National Hospital for Nervous Diseases, Queen Square, London, and at the Institute of Psychiatry at the Maudsley Hospital. He was the author of some 150 scientific papers, co-author of several books on psychiatric topics, and for many years he co-edited Clinical Psychiatry, the leading textbook for psychiatric trainees. He had wide interests including chess (he published a statistical investigation of chess openings), music (he studied and published on the pathography of Schumann and other composers), poetry (he published a book of his own, poetry The Ebbless Sea), and the statistical study of literature. He was awarded a PhD from London University at the age of 77 for a statistical word study of the play Edward III, which provided evidence that the play was by Shakespeare. He died in 1983. This article has been reprinted with the consent of Eliot Slater’s heirs. (http://www.eliotslater.org/index.php/gallery)

Works Cited

Chambers, E.K. William Shakespeare: A Study of Facts and Problems Vol. 1. London, Oxford University Press, 1966.

Chambers, E.K. Shakespeare: A Survey. London, Sidgwick and Jackson, 1925.

Feldman, Bronson. “The Confessions of William Shakespeare” The American Imago #10 (p. 113-166). 1953.

Greenwood, G.G. The Shakespeare Problem Restated. London, John Lane The Bodley Head, 1916.

Johnson, Edward D. The Shakespeare Quiz. London, George Lapworth, 1950.

Knight, G. Wilson. The Mutual Flame. London, Methuen, 1955.

Levin, Harry. The Question of Hamlet. New York, Oxford University Press, 1959.

Looney, J. Thomas. “Shakespeare” Identified in Edward de Vere, the Seventeenth Earl of Oxford, London, Cecil Palmer, 1920.

Nicol, Allardyce. Shakespeare. London, Oxford University Press, 1952.

Rendall, Gerald H. Shakespeare Sonnets and Edward de Vere. London, John Murray, 1930.

Rendall, Gerald H. Personal Clues in Shakespeare’s Poems and Sonnets. John Lane the Bodley Head, 1934.

Rowse, A.L. Shakespeare’s Sonnets. Edited with an Introduction and Notes. London, Macmillan, 1964.

Tucker, T.G. The Sonnets of Shakespeare, Edited from the Quarto of 1609 with Introduction and Commentary. Cambridge University Press, 1924.

Wilson, John Dover, The Works of Shakespeare. Cambridge University Press, reprinted 1969.

Wilson, John Dover, The Essential Shakespeare: A Biographical Adventure. Cambridge University Press, 1932.

Notes

- “The love I dedicate to your Lordship is without end. . . The warrant I have of your honorable disposition…makes it [i.e., this pamphlet] assured of acceptance. What I have done is yours; what I have to do is yours; being part in all I have, devoted yours . . .” (The Rape of Lucrece, dedication.)

- The Sonnets: Preface and Text (edited by John Dover Wilson).

- In this we hear what the poet thought of his own poetry; there is no lack of awareness of success, when his powers of verbal magic captured the immortal phrase.

- A mood disorder caused by internal cognition, a biological stressor.

- A melancholia related to aging.

- To me fair friend you never can be old,

For as you were when first your eye I eyed,

Such seems your beauty still: three winters cold

Have from the forests shook three summers’ pride,

Three beauteous springs to yellow autumn turned,

In process of the seasons I have seen.

Three April perfumes in three hot Junes burned

Since first I saw you fresh which yet are green

(Sonnet 104) - Sonnets 36, 49, and 89 imply that the two men were liable to run into one another in the course of daily life; sonnets 75 and 85 (and others) imply a common social world they both inhabited. Sonnets 57 and 58 depict a personal association that was for a time, very close. Sonnet 113 begins, “Since I left you…”

- Such images do appear in the sonnets concerned with the dark lady. However the imagery that ran riot in Shakespeare’s mind, and finds expression in the Sonnets was very largely visual. Many sonnets show that the capacity for visual imagery was strong, and the images very vivid. Not only could he call up an image of the beloved youth at will, but such images came unbidden both by night (27, 43, 61) and by day (113). Apart from visual imagery, the other sense in which spontaneous images seem to have come relatively freely is the olfactory.

- Rendall in Personal Clues writes: “To the author it was all in all…From the other side…the overtures and professions of affection were welcomed, tolerated, or ignored, as occasion or self-interest suggested; from sonnet 34 onwards, there is nothing to suggest that they elicited much warmth of response, and this is quite in keeping with the Southampton disposition.”

- “Another personal clue…is the strain of sex nausea which runs through almost everything he wrote after 1600. The ‘sweet desire’ of Venus and Adonis has turned sour…possibly due to the general morbidity of the age… That it is not the mere trick of a practicing dramatist is proved by its presence in the ravings of Lear, where there is no dramatic reason for it at all.” A total of nine plays are then discussed. “Collect these passages together, face them as they should be faced, and the conclusion is inescapable that the defiled imagination of which Shakespeare writes so often, and depicts in metaphor so nakedly material, must be his own.” J. Dover Wilson, The Essential Shakespeare, pp. 118-119.

- Even as an empty eagle, sharp by fast,

Tires with her beak on feathers, flesh and bone,

Shaking her wings, devouring all in haste,

Till either gorge be stuffed or prey be gone;

Even so she kissed his brow, his cheek, his chin,

And where she ends she doth anew begin.

(Venus & Adonis, 55-60)

See also lines 553-558. In lines 793-804, Adonis contrasts love and lust in identically the same spirit as sonnet 129. Precisely the same picture of lust is presented in The Rape of Lucrece (ll. 687-714). For the passage in The Comedy of Errors see 3, 2, 109-138; and for the passage in Love’s Labour’s Lost, see 3, 1, 172-204.