David Van Vleck Jr.: How I Became an Oxfordian

November 24, 2015

I’m a playwright/novelist/screenwriter (whose favorite actor is, coincidentally to Oxfordiania, Sir Derek Jacobi). Several years ago, I was at my grandparents’ summer farm in Vermont, and relaxing on our porch, I found myself in conversation with my (now-ex; met another woman on the Internet) brother-in-law, who was citing his mother’s belief that Shakespeare was some guy named Oxford.

Being a playwright and therefore all-knowing re: the theatre, I smugly replied that Shakespeare was an actor who came to London and wrote plays while being a part-owner of a theatre, the Globe. When I returned to my tiny apartment in Brooklyn, to be kind I mailed my brother-in-law a biography of William Shakespeare, a small book, ¼” thick, feeling myself a wonderfully generous person for taking the time to enlighten my sister’s sales/marketing husband.

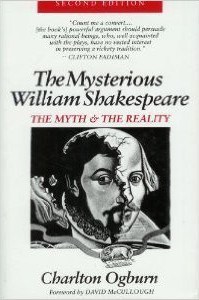

About a week later, in the mail arrived a box from my brother-in-law; I opened it to find a big book, two very fat inches thick, called The Mysterious William Shakespeare by Charlton Ogburn. I groaned, hefting the book’s weight, thinking, Oh great, what conspiracy b.s. must be in here. But, to pay my brother-in-law family respect (and because I had nothing else to do), that evening I opened the heavy tome with a sigh of anticipatory boredom.

Actually before I opened it, I noticed a jacket blurb by David McCullough; I figured, well, maybe McCullough went to college with the author or something and is doing him a favor. I started reading. The first thing I noticed was how well-written the book was, beautiful English, and being foremost a fan of beautiful writing, it was easy to continue reading, though with a sense of, yeah OK whatever.

By page 80 the author had proved, with mathematical-like proof, that Shakespeare couldn’t have been Shaksper the actor/grain guy from Stratford. By page 250, he had ditto proved Shakespeare, “Shake-speare,” was Oxford.

By page 80 the author had proved, with mathematical-like proof, that Shakespeare couldn’t have been Shaksper the actor/grain guy from Stratford. By page 250, he had ditto proved Shakespeare, “Shake-speare,” was Oxford.

From that day, I have known — not wondered, not mostly believed, but known — Oxford was Shakespeare. From the scholarly articles of the Shakespeare Oxford Society (now Fellowship); from finding out Oxford’s Bible exists, with its smoking-gun annotations; from Richard Roe’s book on Italy and the specific landmarks in the Italian plays, that only someone who had been in those cities could have known about; from the fact that Shakespeare employed falconry metaphors in an unconscious manner indicating an intimate familiarity, in an historical period when falconry was almost exclusively a pastime of the English nobility; William Cecil, Lord Burghley, someone all scholars, and Stratfordians, concede was the model for Polonius, was Oxford’s father-in-law; and countless other proofs.

But in a way, most of all, being a playwright/novelist myself and knowing there must be a Why for a (great) writer to write something of profound value, the knowledge that Oxford’s father died when Oxford was 12 and his mother remarried “some time before” 14 months had passed: hmm, that plot sounds familiar. The young Oxford’s pain, seeing his mother remarry so quickly, had to have simmered all his life, and finally brought forth, as the driving narrative Why, from deep old pain inside, the play Hamlet. For me, this is the emotional supreme proof, on top of all the other countless proofs.

— David Van Vleck Jr.

“How I Became an Oxfordian” is a series edited by Bob Meyers. You may submit your essay on this topic (500 words or less in an editable format such as MS Word), along with a digital photo of yourself, to: communications@shakespeareoxfordfellowship.org. Also include a sentence about yourself, e.g.: “John Smith is a business owner in Dallas.” You must be an SOF member to submit an essay.

To join the SOF see our membership page. To read other essays in this series, click here.

Membership dues cover only a fraction of our budget, including all our research, preservation and programming. Please support the SOF by making a gift today!

Blue Boar Tavern: Wassail Q&A

Tuesday Dec. 17, 8pm E / 5pm P

Sign up below for event invites!