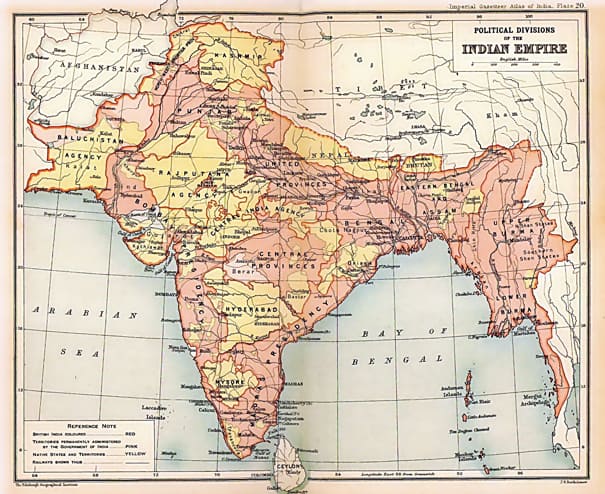

The SOF republishes here, exactly 100 years after it first appeared, a review from “farthest India” of J. Thomas Looney’s book launching the modern Oxfordian theory, “Shakespeare” Identified in Edward de Vere the Seventeenth Earl of Oxford. The book, the centennial of which is being celebrated by the SOF during 2020, was originally published on March 4, 1920, by Cecil Palmer in London. The review was originally published in The Times of India, Bombay (now known as Mumbai), British India, on May 26, 1920.

… Why art thou here

Come from the farthest steep of India?— A Midsummer Night’s Dream, Act II.i.68–69 (Titania to Oberon)

The Times of India, May 26, 1920, p. 11:

THE LATEST SHAKESPEARE.

SHAKESPEARE IDENTIFIED in Edward de Vere, 17th Earl of Oxford. J. Thomas Looney (Palmer).

We live in great days. The mysteries of the world are one by one yielding to the unconquerable mind of man. The discovery of the philosopher’s stone, the conquest of the air, the annihilation of evil and death by Christian science are some of its more recent trophies.

And now Mr. Thomas Looney, out of what he confesses to be his “colossal ignorance” of Elizabethan lore has identified the writer of the plays, which, for three hundred years, we allowed all the learned doctors to persuade us had been written by Shakespeare. Sometimes it happens so, out of the mouth of babes and sucklings. How it happened to Mr. Thomas Looney was as follows.

Repeated readings of the “Merchant of Venice” had forced upon him the thought that nothing in the play corresponded to the outlook of an ill-educated, untravelled, money-making countrified fellow from Stratford. Here was a play-writer full of law and learning, very much at home in Italy, with a complete contempt for gold. His attempts to reassure himself only turned the Stratfordian William into a more and more unsuitable peg on which to hang the plays. Every line of the plays bespeaks an aristocrat, one who in all sorts of unconscious ways failed to understand lower, or even middle-class people, who instinctively betrayed breeding at every turn, even in such externals as skill in dancing, hunting, horsemanship, court procedure, knowledge of French and Latin, of Paris and Italy.

There has always been a bad misfit between the author of the plays and the historical William. The writer’s magnanimity, his breadth of view, his carelessness about money, all fit in very badly with the pettifogging spirit and greed of land which belong to the scanty tale of the Stratfordian worthy. In fact Mr. Looney soon discovered that there was practically no case for W. Shakespeare, and that the authorship of the world’s greatest literary achievement was going abegging.

The striking resemblance of an Elizabethan lyric by one Edward de Vere, seventeenth Earl of Oxford, roused his interest in this possible candidate for the world’s crown of glory, and from the moment that his fingers touched this clue, his search became one of the most exciting and enthralling games that it has ever been a man’s lot to play on earth.

The Earl of Oxford, it soon appeared, had written not one but many lyrics with the most astounding resemblance to “Lucrece” and “Venus and Adonis.” The language, the idiosyncrasies, the experience of the one poet have an incontrovertible likeness to those of the other, and to no other Elizabethan lyrist.

Oxford’s dates fit in exactly with the periods of “Shakespeare’s” known activity and retirement. “Shakespeare” was entirely passive in respect of the publications which took place under his name, but all publication stopped dead for several years after Oxford’s death in 1604. Ovid is the Latin poet to whom all critics agree “Shakespeare” was most indebted, and he used Golding’s translation more than the original. Arthur Golding was Oxford’s tutor, and was at the time studying for the bar, with an interest in the law which he obviously handed on to his pupil.

The conspiracy of silence which enveloped William Shakespeare in life and death calls for explanation. When he died not a single word of regret, not a single obituary notice appeared, though there was loud lamentation for Spenser and other literary contemporaries, and even for Burbage whose funeral overshadowed that of the queen. How is the ignoring of the world’s greatest poet to be accounted for? Spenser was buried in Westminster Abbey; not the smallest reference was made to Shakespeare’s death.

No manuscripts of the plays were found. This genius, who must have foreseen that doubts as to the genuineness of his claims would almost certainly arise, deliberately reduced to a minimum all the evidence that could have established them. There is here the kind of obscurity that only wilful anonymity could have brought about. The Earl of Oxford is known to have retired into mysterious and eccentric retirement during exactly the period of the great “Shakespearian” outflow.

It is impossible to do Mr. Looney justice in a summary, since the effect of his argument is cumulative and in driblets is easily reduced to absurdity. On the other hand he does himself such ample justice that a little less from a reviewer cannot impair his sublime consciousness of having achieved “not merely a national or contemporary event, but a world event of permanent importance, destined to leave a mark as enduring as human literature, or the human race itself. … In the brief moment … between the two immensities Destiny has honoured us with this particular task ….”

Even our old familiar William does not come out of if so badly, since from having been the most stupendous dramatist, he has become the most stupendous fraud in history. He deceived not some of the people some of the time, but all the people all the time.

Editorial Note:

Thanks are due to James A. Warren for unearthing this review during his extensive researches on Looney and furnishing us with a copy. As a publication predating 1925, the original text of the review (like Looney’s book) is in the public domain in the United States (i.e., no longer restricted by copyright) and may thus be freely republished. The editorial apparatus and presentation of the review here on the SOF website are copyright 2020 by the SOF to the extent allowed by law; all rights reserved; permission granted for any nonprofit educational or scholarly reproduction or use, subject to acknowledgment and citation of the Shakespeare Oxford Fellowship and web address of this article.

The original text is in three lengthy paragraphs (beginning “We live in great days”; “The Earl of Oxford, it soon appeared”; and “It is impossible to do Mr. Looney justice”). For ease of reading, additional paragraph breaks have been added here. A few minor and obvious typographical errors, misspellings, or glitches in punctuation have been silently corrected. The images were added here. Click here for a PDF of the original text.

The review’s quotation of Looney at the end has also been silently corrected to conform to Looney’s original. The quotation grafts together two passages at opposite ends of his book, the first part from the first page of Looney’s “Introduction” (p. 13 in the first edition published by Palmer; p. 1 in the first American edition published later in 1920, in New York, by Frederick A. Stokes, and in Warren’s centenary scholarly edition which tracks the pagination by Stokes), and the concluding part (“In the brief moment”) from Looney’s “Conclusion” (p. 497 in the Palmer edition; p. 423 in the Stokes and Warren editions).

[published May 26, 2020, updated 2021]