More Evidence of the Catastrophic Failure of “Professional” Elizabethan Scholarship

by Steven Steinburg

August 30, 2019

[dropcap]I[/dropcap]N THE MISINTERPRETATION of the ‘Rainbow Portrait’ of Queen Elizabeth I, and A Lover’s Complaint by ‘William Shake-speare,’ we find exemplified a failure of scholarship that is, in a word, mind-boggling. It is not simply that thousands of ‘professional scholars’ have been wrong about Shakespeare. For the Academy, and the venerated idea of professional scholarship, that would be cataclysmic enough. But, the failure goes far beyond Shakespeare, and far beyond what even my Oxfordian colleagues have been willing to contemplate.

My claims will be greeted with skepticism, as they should. I would prefer to begin less ambitiously, less sensationally, to take one small step at a time. But it is not possible. All Elizabethan things are connected. In a perfect world what I am sharing here, and what I am about to reveal in several books, should be subjected to intense peer study and review, and not presented unceremoniously as if they are just more musings on what has become the eternal Shakespeare authorship question. Humbly I say I do not have the time or resources. These discoveries are, in my opinion, too important to wait. Review will come. There will be corrections and improvements. With time the truth will be ironed out. Let the debate proceed.

This essay seeks to begin a total revision of our understanding of the Elizabethan era and the man who was the invisible literary giant of one of the greatest literary eras the world has ever seen, and perhaps the single greatest intellect that ever put pen to paper. He was far more than Shakespeare. Far more. The man I am speaking of is Edward de Vere, 17th Earl of Oxenford. I will refer to him as Oxford, though we could simply call him O.

How could it be? How could thousands of scholars be that wrong? How could a failure of such magnitude be possible? The simple answer (though certainly not the complete answer) is the notion that title page attributions must be taken at face value. Exceptions are allowed, but only to preserve orthodoxy. Title page attributions define the interpretive context for Elizabethan scholarship. I would qualify that to say, Elizabethan literary scholarship, except that the misinterpretation of Elizabethan literature, and misattribution, has utterly perverted biographical and historical interpretation for that era.

‘Context is everything’, as the adage goes. It is the key. Take Elizabethan title page attributions at face value and everything that follows is misinterpretation. Interpretive context is crucial to understanding! Therefore, I hope to give the reader enough of the essential interpretive context (as I have interpreted it) to apprehend what is argued here. The argument is divided into a number of parts which, I hope, achieve a degree of narrative linearity. I hope it will be understood that overlap and redundancy is necessary. This essay is a kind of introduction. It is not the argument.

There is, so far as I have found, little if any non-orthodox scholarship on the Rainbow Portrait or the poem A Lover’s Complaint. Oxfordians have been surprisingly silent on both. Prince Tudor (PT) theorists, it would seem, would have drawn a connection to the portrait’s inscription: ‘Non Sine Sole Iris’. In English, ‘No rainbow without the sun’. A simple homophone converts the English translation to, ‘No rainbow without the son’. This could refer to Henry Wriothesley, or to Oxford, subject to the PT theory one prefers. I prefer the latter and that is the direction of my argument. However, the arguments here should not entirely disappoint advocates of the Wriothesley theory. But (and this is important), the phrase, ‘No rainbow without the son’, can also be taken as, ‘No rainbow without the Son of God’. The ‘son’ of a ‘virgin’. Please make a note.

Knowing the skepticism this essay will encounter, I must, for the sake of interpretive context, be candid. I have discovered overwhelming evidence that Oxford and Henry were both sons of Queen Elizabeth. Oxford was not Henry’s father. The father, in both cases, was Robert Dudley. That’s what the evidence suggests. And those brothers had a sister by the same father and mother. Wriothesley PTers may find a way to construe the evidence here to serve their theory. And there are, I know, many Oxfordians who reject all PT theories. God bless both their houses. I say that sincerely. But I humbly suggest they take the time to consider the arguments here, for this is a door to a new understanding of Oxford’s authorship. As for Stratfordians, and ‘professional Elizabethan scholars’, it would take a miracle to cure their institutional intellectual rigor mortis. I’ll not presume to work miracles. But, now to the matter at hand.

The Portrait and the Poem

Among the ‘professional Elizabethan scholars’, Roy Strong is perhaps the most recognized ‘expert’ on the Rainbow Portrait. He says:

All scholars are agreed that it can be dated to about 1600, which would indicate that it was commissioned by Robert Cecil, later Earl of Salisbury.[1]

The problems begin. It is true. ‘All scholars are agreed’, more or less, that the painting dates to 1600-1602. That is close enough for my purposes. And nearly everyone agrees that Robert Cecil ‘commissioned’ the portrait. Now we have a major disagreement! That is impossible. I say that with a caveat that I will discuss at the very end. The true meaning of the portrait tells us the motive behind it, and that motive tells us who it was that masterfully conceived that Trojan horse. That person could only be Oxford, the secret and profoundly frustrated son of the queen. And this tells us, among other things, that Oxford’s artistic genius was not limited to words.

One tell-tale sign that this portrait was, and is, a Trojan horse, is that it bears neither a date nor a signature. Why would the artist of such a marvelous and provocative portrait not want to take credit for his work? True artists are generally good judges of their own work. The painter of the Rainbow Portrait undoubtedly recognized that that painting was one of his most important works, and that, for the purpose of future commissions, it would be excellent advertising. But, he also knew that that painting was not just a Trojan Horse, but a ticking revelation-loaded time bomb. The anonymity of the artist served to protect the artist in the event that bomb went off prematurely, and it ensured that people wouldn’t be able to put troubling questions to the artist, for a while at least. Word eventually leaked out that the artist was Marcus Gheeraerts the Younger. By then the Trojan horse was a glorious success. Everyone loved it, especially the queen, although, if the dating we have is correct, she died only a few months after viewing the portrait. But, she’d never looked so gorgeous. The artist sighed a sigh of relief. The bomb would go on ticking for some four hundred years.

The Rainbow Portrait has not been regarded, by Stratfordians or Oxfordians, as relevant to the Shakespeare authorship question. Although orthodox scholars have not felt particularly compelled to find explanations or interpretations that are congenial to the Stratfordian tradition, they have been guided by the necessity of devising explanations that do not upset the conventional wisdom, at least not too much. As we shall see, not all of the interpretations have been entirely conventional. Valerie Traub sums up the generally agreed upon starting position:

Even as this notoriously enigmatic painting interweaves a complex skein of religious and political allusions, two aspects of its iconography are particularly relevant to our consideration of Elizabethan eroticism: the disembodied eyes, ears, and mouths arrayed on top of her clothes, and the colorless rainbow in Elizabeth’s hand.[2]

‘Colorless’. Please make a note. But, I have two important objections to the above. First of all, the idea that examining this painting through the lens of ‘Elizabethan eroticism’, or ‘Elizabethan gender perspectives’, as it is sometimes referred to, illustrates what happens when academics are constrained by an interpretive context that is uniquely fraught with ambiguity and paradox; that is, where authorial disconnection is the norm. I would say, take Shakespeare for example, but, though it has hardly been noticed, the problem extends beyond Shakespeare, to Sidney and Spenser, and many other names. Since the ‘professional’ scholars cannot find the biographical authorial connections and cannot link the works to personal interests and motives, they resort to explorations of cultural generalities. The result is an academic dead end and literally tons of academic drivel.

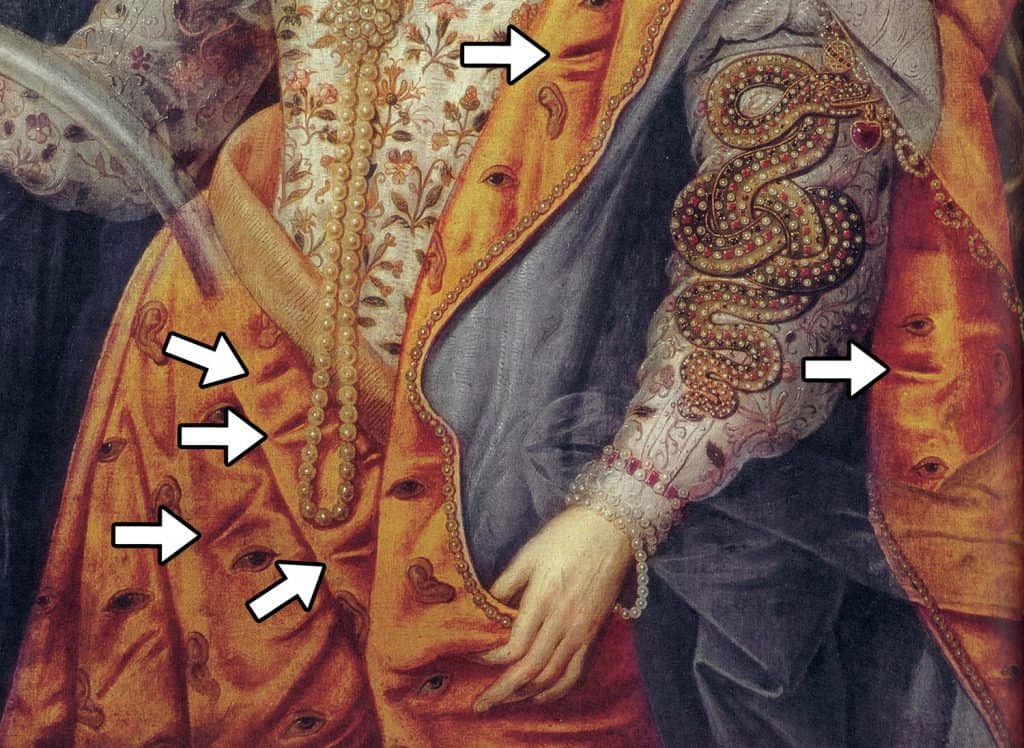

Getting back to the example at hand, my second objection is that Traub cannot see the forest for the trees. In a discussion of graphic symbolism, where details are extremely important, she makes the amazingly erroneous statement that the, “eyes, ears, and mouths arrayed on top of her clothes”. No they are not! Those ‘eyes, ears, and mouths’ are on the liner on the inside of Elizabeth’s cloak! The inside! I will repeatedly come back to this, for it is absolutely central to the meaning of the portrait and to discovering the purpose and motives behind it.

On the matter of the mouths (that Traub does see), expert opinion is split. The mouths are a problem. Roy Strong decided the matter this way:

A detailed examination of this garment shows no signs of the mouths read into it by scholars . . .[3]

A ‘detailed examination’? How? By whom? We’ll come back to that as well. Traub is certainly correct that the portrait is ‘notoriously enigmatic’. Everyone will agree to that. She is misguided, however, in her assumption that the true meaning can be accessed by way of religious and political allusions, or even, as she proposes, by way of erotic symbolism (intentional or unintentional). In fact, as we shall see, the evident religious and political symbolism in the portrait are merely the first level of meaning aimed at naïve viewers, like Strong, and even Traub or Fischlin, who are bolder in their reading of the portrait.

The most obvious problem with the portrait is not any particular symbol, but the ambiguity of the symbolism. This fact alone should have set off warning bells in Robert Cecil’s head. Robert Cecil was Elizabeth’s Secretary of State. But he was also, secretly, her Lord High Minister of Spying and Propaganda. He’d learned from the best, his father, William Cecil, Lord Burghley. Robert Cecil may not have been sophisticated in his knowledge of symbolism, but he understood how to use symbolism as a tool of propaganda. For his purposes symbolism needed to be easily understood. He understood the danger of ambiguity. It is a mystery, therefore, that the Rainbow Portrait ever saw the light of day, let alone remained on proud display.

It was too beautiful! Especially compared to all the other portraits of Elizabeth. It is sumptuous! One look at that portrait and you fall in love. The beauty of that portrait and its instantly addictive effect tell us something about the person who designed it. And there was a good cover story.

It’s one thing to throw a bunch of symbols together. It’s another thing to weave such symbolism into a magnificent dramatic work of art with a coherent underlying narrative. Expert opinion now tends to the identification of Marcus Gheeraerts as the artist, and I will provide evidence (new I think) that he was in fact the artist.

Gheeraerts was an accomplished artist, but he is surely not the person who composed that portrait or devised the details. And that person was surely not Robert Cecil. He had neither the artistic sense nor the motives. This is an extremely important point. Unless we have totally misread Robert Cecil’s motives in the final years of Elizabeth’s reign, his went quite the opposite direction. This has not occurred to the scholars even though they have observed many things about the portrait that seriously conflict with the assumption that Cecil commissioned it. It seems to me that scholars who have, with seeming authority, commented on the portrait, have very little understanding of the historical-biographical background.

A few years after the portrait went on display a little ‘book’ appeared with the title William Shake-speare’s Sonnets. You may have heard of it. Near the back, almost hidden, unmentioned on the cover or title page, was a 47 stanza poem called A Lover’s Complaint. Here’s what the attribution on the first page of the poem looked like in 1609 (figure 2):

Note the small print used for the name. I’m guessing that was the smallest print-type available or possible at the time. The poem didn’t get much attention. It didn’t seem like much of a poem. To lots of folks it didn’t even seem much like Shakespeare. Not long ago Ron Rosenbaum described it as a “bad” poem.[4] Some scholars have deemed it so ‘bad’ they refuse to accept that Shakespeare wrote it. Breaking the most sacred rule of Elizabethan literary scholarship (‘Title pages don’t lie’), Brian Vickers overrules the explicit attribution of the poem saying:

Shakespeare did not write A Lover’s Complaint, and the sooner it is removed from his canon, the better. The real author, as I have argued, is the prolific but mediocre poet and writing-master, John Davies of Hereford.[5]

John Davies was a ‘mediocre poet’. However, Brian Vickers’ dubious methodology, and his depreciating contributions to ‘attribution studies’, if believed, would make attribution and authorship meaningless. But then, the Stratfordian Tradition has already done that for Shakespeare. However, as it relates to the Rainbow Portrait, Vickers’ assertion that John Davies was the author of A Lover’s Compliant turns out to be a curiously coincidental proposition, as we shall see.

Until two years ago I did not think that A Lover’s Complaint was important. I don’t think any of us Oxfordians thought it was important. I would have agreed with Rosenbaum that it was “bad”; not worth the time. That assumption, my friends, was a monumental mistake (in a double sense). I’m only going to touch briefly on that monumental poem in this article, and I don’t expect to convince the reader at this time, but A Lover’s Complaint, I confidently assert, will come to be regarded as one of most important literary works of all time, not as poetry, but as an utterly unique form of narrative that tells a history-changing story.

To understand that poem there are a couple of things one must understand about Oxford. I know that sounds presumptuous. Bear with me. We, Oxfordians, have not had a proper appreciation of his playfulness, his often risqué sense of humor, his incessant use of riddles, or the scope of his genius, nor (this is vitally important) have we understood his motives or the depth and sincerity of his humanity. We have not understood his desperate need for authorial connection, and how he has been reaching out to you and me. And there is the huge problem that there has been no understanding of his method of concealed storytelling, what he called his science. For an introduction to that science I refer the reader to my recently released book, Renaissance of Lies. For an in-depth discussion of A Lover’s Complaint, please see my other soon-to-be released book, Resurrection.

Wishy-Washy Scholarship

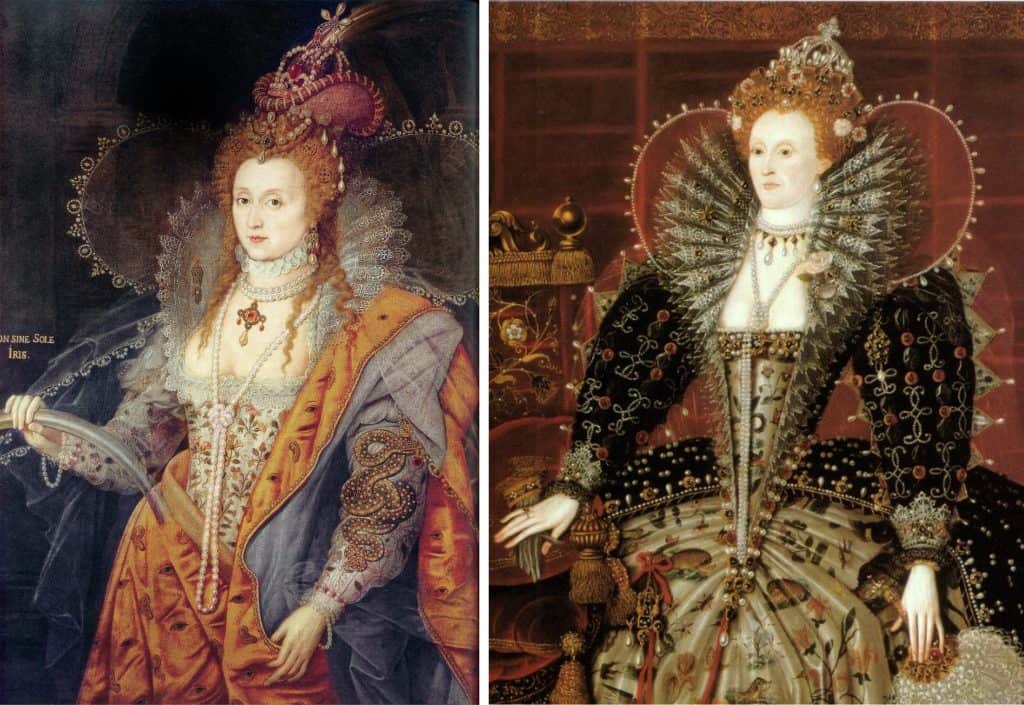

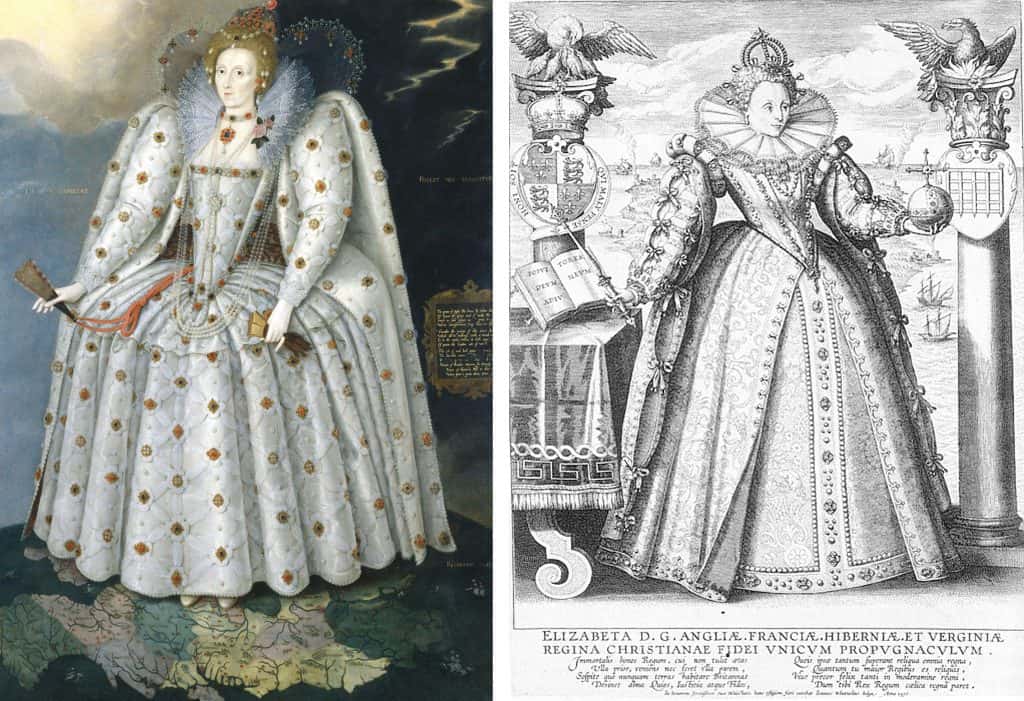

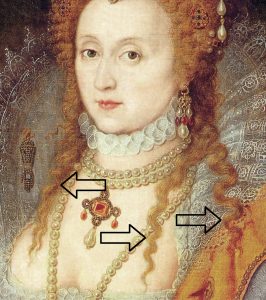

With the possible exception of the Coronation Portrait, the Rainbow Portrait is by far the most flattering of Queen Elizabeth’s portraits. It is, to be sure, the sexiest. Elizabeth was nearly seventy at the time it was painted (per the generally accepted dating), and she obviously didn’t stand model for this portrait. One of the models was most probably this slightly earlier portrait which I place side by side with the Rainbow Portrait (figure 3):

Both portraits appear to use the same or very similar wig (an important point). Both use the same long pearl necklace (another important point). Both use a similar huge gossamer wing-like apparatus, etc. In contrast, however, Elizabeth’s gaze in the Hardwick is off to the side, cold, almost disdainful, disinterested in the viewer. The lady’s gaze in the Rainbow Portrait is direct, warm, and alluring. Notable are the three strands of hair that ‘descend’ along the cheeks onto the breast in the Rainbow Portrait (another important point!). By contemporary standards, ‘loose hair’, ‘loose woman’, generally speaking. The ‘loose hair’ is unique in Elizabreth’s portraits except for the Coronation portrait and certain cameos. The torso in the Hardwick is stylized in a stiff unnatural cone-shape. The bosom is flat. In the Rainbow Portrait the upper torso is natural and there is a visable plumpness of the breasts. One can almost see the nipples.

Comparing Elizabeth’s face in the Rainbow Portrait to her many other portraits, the painter has taken considerable liberty in enhancing her appearance. In the Rainbow Portrait the head is proportionately larger, the face is wider, the eyes are larger, wider set, and more expressive. In the Hardwick the head and face are slightly pulled back as if in recoil. We see the typical pale pastiness that came to characterize the queen. In the Rainbow Portrait the paleness is deemphasized and the facial appearance is more natural. There’s nothing ‘corpse-like’, ‘ghostly’, or ‘carcass-like’ about the lady in the Rainbow Portrait. That woman is confident but relaxed, vital, sensuous, and alluring. The cloak is sumptuous. The colors are warm and welcoming. It is undoubtedly the most convivial of all of Elizabeth’s portraits. Forgive me if I am pointing out what is obvious.

In describing the scholarship on the Rainbow Portrait I would use words like speculative, superficial, naïve, even sloppy, but most of all I would use the technical term, wishy-washy. This is true of Elizabethan scholarship in general. Wishy-washy! Let us set forth with Frances Yates who serves as the starting point for most of the available scholarship on this painting:

If the portrait of Queen Elizabeth I at Hatfield House, usually called the ‘Rainbow portrait’…is placed beside Boissard’s plate of a ‘Sponsa Thessalonicensis…it is immediately apparent that the curiously-shaped upturned head-dress of the portrait, with the striped rim and surmounted by an aigrette, has been suggested by the head-dress of Thessalonica. The flowing mantle worn in the portrait, and the position of the hand which raises it, might also have been suggested by Boissard’s figure…. The allegories of the picture are also highly applicable to Elizabeth: the rainbow shows her as a peace-bringer; the eyes and ears with which the robe is covered alluded to her fame; the serpent on the sleeve indicates her wisdom; and above the serpent’s head is the celestial sphere, encircled with the band of the zodiac, which is a symbol elsewhere found in connection with Elizabeth (for example in the ear-ornament which she wears in the Ditchley portrait).

The clue to this picture may be that it records Elizabeth’s presence at some masque in which allegories in her honour were presented by various personages but which are now summed up in a composite portrait of herself.[6]

There are a number of important points I want to emphasize: 1) Yates detected the connection of the ‘headdress’ in the portrait to the figure of Sponsa Thessalonicensis in Jean Jocques Boissard’s ‘costume book’, Habitus variarum orbis; 2) Yates noted that the figure in the headdress is a bride and that the hat is a bridal headdress.[7] However, Yates does not address the problem presented by a virgin queen wearing a bridal headdress; 3) Yates noted the ‘striped rim’ of the headdress; 4) Yates says that “the eyes and ears with which the robe is covered alluded to her fame”. However, Yates does not mention mouths; 5) Yates says that, “the serpent on the sleeve indicates her wisdom”; 6) Yates concludes that the various features of the portrait may represent a ‘composite’ from costumes worn at an event attended by the queen.

Yates ignores the problem of the bridal hat and explains very little about the portrait and the motives behind it. It appears that, within the alleged ‘composite’ nature of the costume and symbols, Yates takes some of the symbols to be simple decoration. This is very important. If she’s right, the symbolism of the portrait should not be taken too seriously. Interpretation of the portrait is, then, a harmless pastime. It seems to me that, given that the portrait practically screams at the observer to study its symbolism, the inclusion of simply decorative (and inherently contradictory) symbolic elements is counter-intuitive. René Graziani observes:

As well as being one of the most radiant images of her, this portrait is one of the most insistently symbolic. Was the sense meant to be plain or is it calculated to be obscure? [8]

I would say, ‘insistently and intensely symbolic’ and ‘obviously obscure’. The portrait is, in a word, provocative. If we are inclined to reject wishy-washy explanations, we ought to grant that the mastermind behind that obscurity and the provocation knew exactly what he was doing; and I think it is logical to assume that the portrait’s use of symbolism is intended to be meaningful and congruent in the story it tells. The painting is too intense in its projection of meaning, too precise and complex, too obviously intentional in its provocation, to allow a loosy-goosy explanation about commemorating a ‘costume event’.

While scholars have more or less embraced Yates’ ‘composite’ explanation, the main focus of scholarship on the painting has been, nevertheless, to guess the meaning of the problematic symbolism. It ought to be obvious that such explanations require a theory as to the persons and motives behind the portrait. This has not been obvious to the scholars. They don’t even mention it. They persist in the improbable assumption that Robert Cecil commissioned the portrait. This exemplifies the superficiality of the available scholarship. And so it is that the orthodox scholars have naively rolled Oxford’s Trojan Horse into their orthodox city.

Getting down to details, the biggest most obvious specific problem are the eyes and ears and mouths on the marvelous orange-golden liner of the cloak. I say again, on the liner! For these provocative features, scholars have come up with three principal explanations: 1) they represent Elizabeth’s ability to ‘see all and hear all’; 2) they represent her fame; 3) the symbolism of the portrait is a hodge-podge ‘composite’ and doesn’t mean anything in particular.

And then there is that strangely colorless rainbow. That, too, has generated some very interesting interpretations. All of this, among the scholars, remains unsettled. However, I think it is fair to say that no one is losing any sleep over it (though they should). In the minds of the ‘professional scholars’, the portrait is just another unimportant Elizabethan mystery. That said, a few of those scholars have ventured down some surprisingly exotic, erotic, and not entirely benign paths. Take, for example, Valerie Traub:

Increasingly, the rainbow is interpreted not only as a royal scepter but as an ambivalent image of phallic power (bent, nor erect), while the open mouths, ears, and eyes, along with the folds of the mantle itself, have been viewed as disturbingly vaginal. For Susan Frye, these body parts “form a disquieting suggestion of vaginal openings,” while Joel Fineman calls attention to the “salacious ear that both covers and discovers the genitals” of the Queen. For Daniel Fischlin, the “ambiguous folds, in combination with the vague phallic rainbow and the string of pearls looped suggestively round Elizabeth’s genital area, image an erotic potential complicit with the sovereign vitality the portrait projects. Elizabeth’s metaphorical embrace of the phallus, whether construed as an assimilation and erasure of masculine power or a prosthetic supplement to her own body, confirms her status as actively desiring, erotically commanding, and self-pleasuring. The relative position of the rainbow and hands enhances this reading: just as the visual line of the rainbow fades toward the genital area, the thumb and bent index finger of Elizabeth’s left hand are inserted into the folds of her mantle. As Fischlin remarks, the “subtle visual and figurative resonances of the fold” intensify the female-centered bodily imagery, insinuating a masturbatory erotics that “rescripts the sovereign’s potency in terms of both masculine and feminine agency.” Grasping the phallus and touching herself, Elizabeth would seem to possess double access to pleasure.[9]

Fascinating! And, drawing on Daniel Fischlin directly:

The portrait’s compositional balance entails an erotics in which the queen exerts control over the masculine, a control that may be further heightened by the sexual autonomy suggested in the positioning of her left hand. A further possibility is that the Rainbow emblematically endows her with masculine attributes and that, in a sense, she becomes male by virtue of her grasp of its cylindrical shape as it descends onto and merges with her anatomy.[10]

Traub and Fischlin are getting dangerously warm. However, if this symbolism was intentional (and I assume that is what Traub and Fischlin are saying), I think one would have to say, ‘Holy cow!’ How amazingly counter-intuitive and subversive! But, curiously, no one seems to be saying that. Fischlin does express the concern:

Reading the folds in the mantle as mouths — themselves a visual metonymy [rhetoric] for the vagina — is extremely problematic with regard to the apparent logic of the portrait’s representation of the “queen’s chaste body.”[11]

In spite of this concern that, so interpreted, such symbolism “is extremely problematic”, neither Fischlin nor Traub, nor any of the other scholars mentioned here, pursue a practical explanation for purpose or motive. As I said, no one really cares, amazingly. And I say again, the reason no one cares is that the mysteries of the portrait fall within the Elizabethan era which has been deemed characteristically mysterious, ambiguous, and paradoxical. For no other era of history, or place, do ‘historians’ avail themselves of these anti-historical shoulder-shrugging wishy-washy work-arounds. Take, for example, the notion that William Shakspere wrote Shakespeare. But I digress.

So, what I find missing in Traub and Fischlin’s remarkably provocative interpretations is an explanation for how, on earth, that kind of dicey subversive symbolic meaning can be mated up to the presumption of Robert Cecil’s complicity. Or are Traub and Fischlin saying that this symbolism is inadvertent, a kind of accidental Freudian slippage in the mind of the person who devised the portrait? I don’t think that is what they are saying. I’m not at all convinced that they know what they are saying. I say, therefore, that this is a huge historical problem with huge implications. Why is no one dealing with it? That’s a rhetorical question. It is time to deal with it. But first let’s consider some more conventional interpretations of the Rainbow Portrait and how it came about.

The Purpose and Motive Behind the Portrait

There is almost universal belief that the portrait is connected to one of several entertainments that the queen attended at the house of Robert Cecil between 1600 and 1602. With this goes the assumption, again, that Robert Cecil was the commissioner of the portrait. The ‘professional’ scholarly arguments, as we shall see, fall short of clarity, draw on questionable or erroneous information, are highly speculative, and are, in a number of cases, remarkably sloppy. But again I repeat myself. And I think it is fair to say that we are talking about the best of ‘professional Elizabethan scholarship’ on this particular topic.

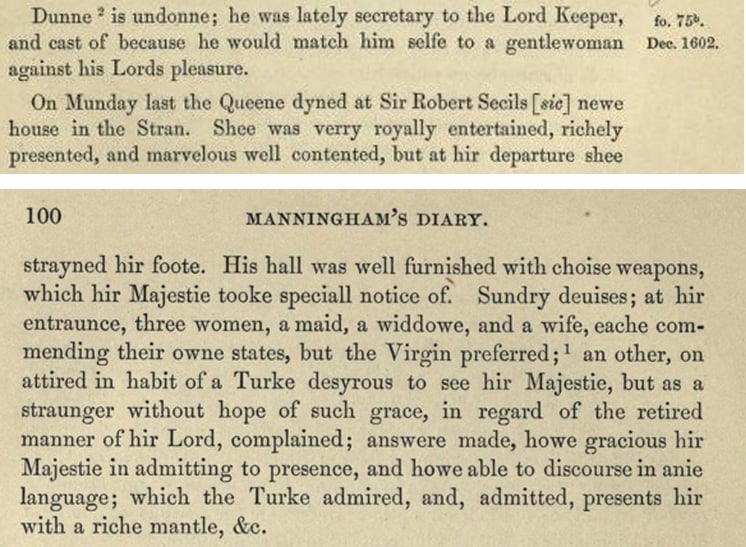

Getting down to the excruciatingly confusing detail (which I hope to unravel), as the popular arguments goes, the portrait is connected to a poem by John Davies (the person, coincidentally, to whom Brian Vickers attributes A Lover’s Complaint). Allegedly, this poem by Davies, a kind of dialog called A Contention Betwixt a Wife, a Widow, and a Maid, was read or performed for the queen on the occasion of her visit to Robert Cecil’s ‘new house’ in 1602. We can be confident in this dating. John Manningham recorded the following in his Diary with a date of December 1602 (figure 4):[12]

Allardyce Nicoll dates the entertainment (and the presentation of Davies’ poem) to 6 December 1602.[14] Notably, that was just short of four months before Elizabeth died. At any rate, for the scholars, Davies’ Contention becomes a basis for safely interpreting the symbolism in the portrait centering on the queen’s virginity and fame, more or less. However, making a fuss over Elizabeth’s fame and virginity was like putting more icing on an already over-iced cake. To everyone in England, and probably Scotland and Ireland, Elizabeth was the most famous living person in the world. Everyone knew she was the Virgin Queen. Anyway, the presumptive ‘connection’ of these clichés to the portrait is drawn from the ‘victory of the maid’ (a virgin) in Davies’ poem. According to Mary C. Erler:

The connection between Davies’s poem, Boissard’s engraving, and the Rainbow Portrait is further strengthened when we notice that, in the Rainbow Portrait’s headdress, the triumph of virginity over wife-and widowhood, which is the point of the poem, has been underlined by the painter’s adaptation of Boissard.[15]

To say that the maid’s victory was a ‘triumph of virginity’ (another cliché associated with Elizabeth) is something of an exaggeration. The poem is accessible on the internet. It’s nothing extraordinary, but maybe worth reading. As the Contention goes, a widow and a wife engage in a teasing debate with a maid. The point of contention is who should lead the ceremonial offering to the virgin goddess Astraea. Predictably, the two once-upon-a-time virgins eventually concede and allow the maid to win the argument and lead the offering. It might be observed that, within this symbolic contention, we have the maid (representing Elizabeth) paying homage to Astraea (also representing Elizabeth). This little dialog would have served the ceremonial bootlicking of the queen and her virgin persona that had become obligatory at such occasions. However, the virgin symbolism pertaining to Elizabeth being the very epitome of cliché at that time, what is it, we may ask, that especially connects the Contention to the Rainbow Portrait?

It gets a bit complicated. It has to do with: the lady’s costume; especially the hat; John Davies’ poem; Henry Peacham’s Minerva Britanna; Boissard’s Habitus variarum orbis genitum; and Caesar Ripa’s Inconologia. Bear with me. I will go slowly. We will sort this out.

I want to pick up here on the most penetrating (this may be taken as punning innuendo) analysis of the Rainbow Portrait that I have found, that of Daniel Fischlin. Having penetrated deeper than all of his colleagues, having clawed his way to many insightful, and above all, disturbing observations, it is Fischlin who faces the greatest challenge to explain what he found. And he makes no attempt. This inevitable failure is telegraphed in the title of his essay: ‘Political Allegory, Absolutist Ideology, and the “Rainbow Portrait” of Queen Elizabeth I’.

One is forced to ask, what ‘political allegory’ and what ‘absolutist ideology’? He says:

A number of features in the portrait combine to form a forceful, political allegory that is presented within a complex skein of allusions, not all to be read in terms of traditional iconography …the resonances of the portrait, whoever drew up its program, may not have been wholly within the interpretive traditions of Elizabethan portraiture.[16]

Okay. But, where’s the beef? What exactly were those political statements? What was the motive for making those statements in this portrait? And who was motivated to “draw up its program”? Fischlin says:

The portrait, no doubt, is a hybrid—aesthetic, religious literary, and so forth—but it is a hybrid designed in such a way as to occlude the overt political significations that would have undermined it as political representation.[17]

A “representation” of what exactly? To what purpose? How can this be squared with the assumption that Robert Cecil commissioned the portrait? We have a clear idea of the kind of ‘political representation’ Cecil would have orchestrated. Why would he (or any other loyalist associated with Elizabeth’s court) suddenly veer off in the direction of a deeply problematic ‘political’ (and erotic) message that needed to be ‘occluded’ or obscured from general view? Ignoring these questions while amplifying their importance, Fischlin continues:

The very fact that commentators have missed or ignored the political symbolism at work in the portrait indicates either that it is so obvious as not to warrant mention, or that it is so cleverly concealed as to be virtually unnoticeable. If the latter option is indeed correct, then the highly accomplished features of the painting may well serve to distract viewers from the cryptic and dissimulative artifices that are the keys to the portrait’s allegorical dimensions.[18]

Fischlin’s reasoning is on target, but there is no follow-through. He only gets far enough beyond generalities to construe an obscure message that he leaves motiveless and completely unexplained. He says:

Those dimensions include the political insofar as the portrait comments on monarchic governance in the anxious, historical contexts of a sovereign who, without direct heirs, was near the end of a reign in which some measure of political stability, however illusory, had been achieved. Though commentators have averted their eyes from the political dimensions, preferring instead to reflect on the general structure of the portrait, it seems clear that the portrait intends a political allegory, however, concealed, that comments on the dimensions of the absolute ideology it enacts….[19]

Let us say the painting is ‘enacting an occluded absolute political ideology’. So what? What is the point? Who was the intended audience for this ‘unnoticeable’ message? Like a police detective who finds a bloody crime scene, a body, and a murder weapon, but who has no intention of looking for the murderer, Fischlin just keeps pointing to the clues at the crime scene. Solve the crime? The idea didn’t occur to him. But he does quote W. J. T. Mitchell:

“We can never understand a picture unless we grasp the ways in which it shows what cannot be seen”.

And then Fischlin falsely claims:

My reading of the Rainbow portrait attempts precisely this task by way of the covert ideological structures relating to absolutism on which the portrait comments.[20]

No, Fischlin does not ‘attempt to be precise’ with respect to meaning which, I insist, cannot be separated from purpose and motive. To a degree Fischlin has ‘seen’ beyond what is overt, but he has not ‘seen’ enough. He is blinded by the conventional interpretive context. Most importantly, he has not ‘seen’ that the eyes and ears and mouths (collectively, the most important element of the portrait’s narrative) are demonstrably where they normally “cannot be seen”, that is, as I will keep saying, on the inside of a cloak! Fischlin says:

The second element of the portrait that has not received much commentary is the Queen’s cloak, with its eerie depiction of eyes and ears facing out toward the viewer.[21]

‘…toward the viewer’! That is as close as Fischlin comes to observing the most important clue in this painting. Not Fischlin, nor any of the ‘experts’ I have consulted, have commented on the entirely ‘noticeable’ fact that the cloak is a cloak of secrecy! Nothing in the painting is more pregnant with meaning than that; and I say again, amazingly, absolutely no one seems to have noticed. Fischlin says (underlines added):

John M. Archer reads the folds as “tongues” (4), the shift from Frye’s to Strong’s to Fineman’s to Archer’s interpretation of the folds indicating the difficulty critics have had attributing meaning to the folds, itself a particularly canny iconic representation of a sliding signifier. The painting clearly eroticizes Elizabeth’s body, whether or not one sees the portrait in the same way as Fineman, Frye, Archer, and Strong. The ambiguous folds, in combination with the vaguely phallic rainbow and the string of pearls looped suggestively round Elizabeth’s genital area, image an erotic potential complicit with the sovereign vitality the portrait projects. Moreover, the capacity to transfix with both an erotics of ambiguity and an ambiguous erotics fortifies the absolutist dimensions of the portrait…[22]

Fischlin wanders off into a fog of academic gobbledygook; “erotics of ambiguity” and “an ambiguous erotics”. I will point out again the general problem that Elizabethan scholars accept ambiguity as an answer, which is nonsense, historically speaking. And this ‘ambiguity’ was commissioned by Robert Cecil? In my non-academic opinion, Fischlin’s idea of “absolutist dimensions” is too ambiguous to explain anything. However, if he is correct (and I am sure he is), that the painting ‘eroticizes Elizabeth’s body’, what was the motive? What was the purpose? Did the painter sneak that in? Was he taking liberties to satisfy his need for artistic expression? Highly improbable. But, consider how far Fischlin goes with this dangerous interpretation (underlines added):

Furthermore, if the queen’s left hand, with its index finger inserted in one of the mantles folds has some sort of masturbatory significance, again if one accepts Frye’s sexualized reading of the mantle’s folds, then the painting seems to be asserting, however cunningly or ambiguously, the Queen’s sexual aloofness, itself a metonymy for her political uniqueness. The portrait may slyly hint, however shocking such a suggestion may be, at the nature of the unmarried queen’s autonomous sexual practices while also affirming the queen’s political authority by virtue of the gaze she maintains and the intelligence she receives while touching herself.[23]

Let us say that this obscure tangle of sexual and political meaning is meaningful. I ask again: Motive? Let us remember the Coronation Portrait (figure 5):

It is easy to overlook that, in the history of Europe, England’s Virgin Queen was something extraordinary. And by way of the generally accepted conceit, she was the Faerie Queene, the incarnation of Astraea and Diana, a goddess, a supernatural being. For England, for more than four decades, she was the center of the political universe, real and make-believe. Any symbolic or personal message about the queen was ‘political’ and much of it loaded with romantic-religious-mystification. I think it is reasonable to say that the messaging Fischlin is inferring is fundamentally subversive. I ask again: who would be behind such messaging? Unless I have misread Fischlin, he never asks these questions. No one does. But he is very warm. He is only centimeters away from the meaning he cannot see. He quotes Frye:

“[Elizabeth’s] body as the center of a Ptolemaic universe while wrapping her in a mantle whose open mouths, ears, and eyes form a disquieting suggestion of vaginal openings combined with a sense of governmental surveillance”[24]

Critiquing, Fischlin says:

Frye does not develop her “suggestion of vaginal openings” nor their relationship with governmental surveillance, if any at all.[25]

But, neither does Fischlin “develop” his ‘suggestions’ into anything probative or substantial. He does not take the next step to connect the alleged messaging to a practical purpose and motive. He says:

Reading the folds in the mantle as mouths—themselves a visual metonymy [rhetoric] for the vagina—is extremely problematic with regard to the apparent logic of the portrait’s representation of the “queen’s chaste body.”[26]

Indeed, ‘extremely problematic’! And? Imagine your doctor saying, ‘You have a deadly infection that needs to be treated immediately with antibiotics. Have a nice day!’ Somewhat earlier Fischlin says:

…if the erotics of the portrait entail a contemporary reading of the mantle’s folds as mouths or vaginas, the political dimension of the queen’s erotic allure cannot be ignored.[27]

But, in terms of purpose and motive, Fischlin does ignore them. He goes much further than any of his colleagues in paying attention to them, only to walk away from the problem. Fischlin leaves us adrift with his idea of ‘Political Allegory’ and ‘Absolutist Ideology’, whatever that means. Let’s see if we can find our way to shore.

An Oxymoronic Hat

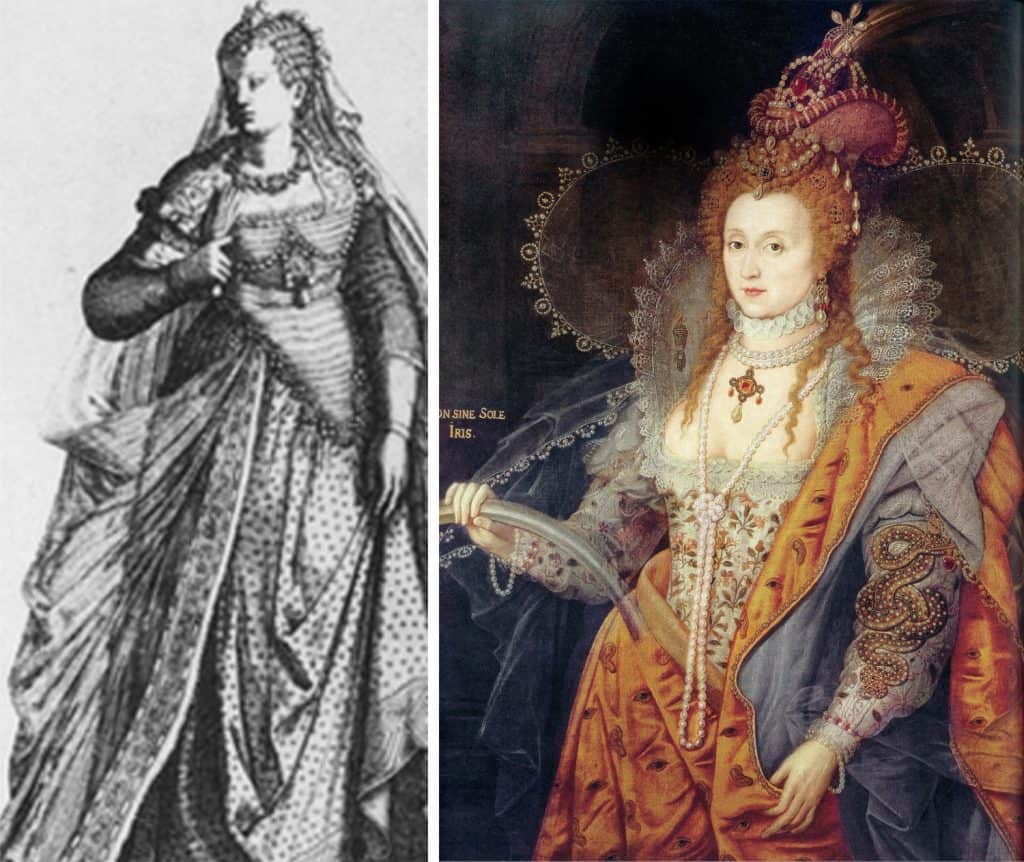

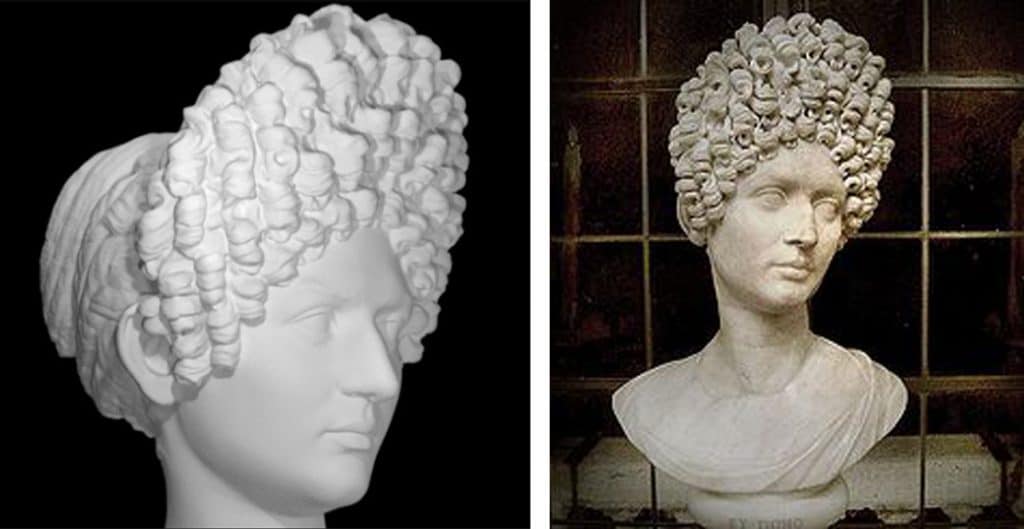

Where did the idea for this hat come from? Dame Frances A. Yates tracked it down (figure 6):

Above, on the left, is the hat from the Rainbow Portrait. On the right (reversed from the original) is the be-hatted head of the figure called ‘Sponsa Thessalonicensis’ from J. J. Boissard’s Habitus variarum orbis gentium (‘Styles of the Various Peoples of the World’), published in 1581. Here’s the full plate from Boissard (figure 7):

If you want to examine this plate, or the other plates, you can access Jean Jocques Boissard’s book for free via the internet.[28] Thessalonicensis refers to the Greek city of Thessalonica, aka, Thessaloniki, Salonica, or Salonika. It is the second-largest city in Greece. But, here’s the problem: Sponsa Thessalonicensis means ‘Bride of Thessalonica’. The lady’s hat is a bridal headdress. The point I am emphasizing is that, to be a bride bears the non-negotiable implication of giving up one’s virginity! How is a bridal headdress appropriate symbolic attire for a perpetual Virgin Queen?

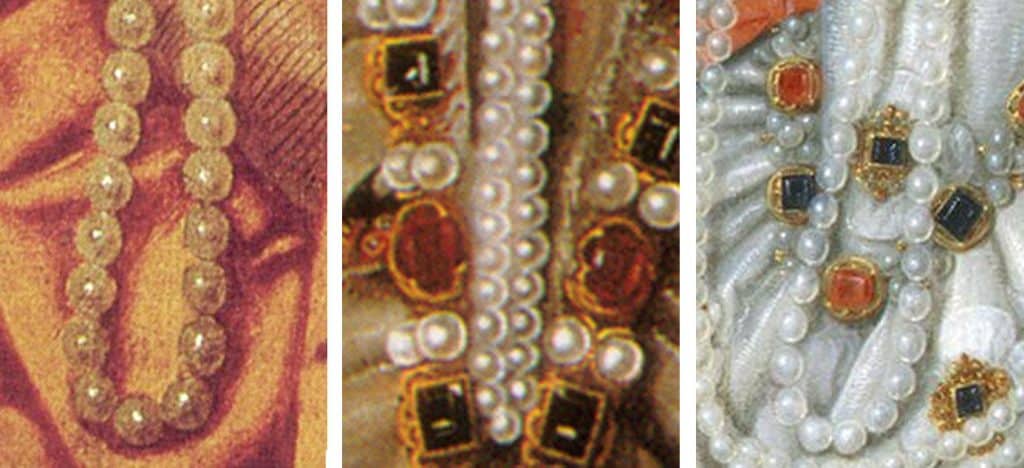

Examining the bridal hat, with its integral crown, we find multiple symbols of virginity (feminine purity), including white pearls and a crescent moon (one of the major symbols for the chaste virgin goddess Diana) (figure 8):

How do the scholars deal with this oxymoronic headdress? Mary C. Erler says:

Finally, she [Yates] discovered the similarity between the portrait’s headdress and that of a figure labeled “sponsa Thessalonicensis” in J. J. Boissard’s Habitus variarum orbis gentium (Cologne, 1581): consequently she suggested that both this painting and two others might represent the sitter in masque attire which had been adapted from a book of costumes.[29]

Where this is headed is Yates’s idea, as previously mentioned, that the portrait represents a ‘composite’ of costumes. Yates’ intent is, as I understand her, to have it both ways, to take the symbolism seriously in some parts and not take it seriously in others. As for the hat, Yates seems to take the latter course. The problematic hat is just decoration. Again I am repeating myself. It seems to me that, in a portrait that is screaming ‘Look at my symbolism!’ that makes no sense. But let’s see where this goes. Continuing her argument for more or less meaningless symbolism, Erler says:

Each plate in Boissard’s book shows three figures of equal size, arranged side by side, who illustrate the characteristic dress of a single city or country. Thus Plate 38 (fig. 2) presents three female figures captioned “Sponsa Thessalonicensis,” “Foemina Thessalonicensis,” and “Virgo Thessalonicensis.” The plate, that is, provides the typical costume of a wife, a woman, and a maid of Thessalonica, or Salonika. Yates, in demonstrating the Sponsa Thessalonicensis’s headdress was the source of Elizabeth’s in the Rainbow Portrait, reprinted only the figure on the left side of the plate. It seems likely, however, that it is the plate’s presentation of three female figures grouped together which caught the eye of the Cecil entertainment’s designer—three figures who correspond closely with the three women of Davies poem performed for that occasion. [30]

Thus taken, the portrait’s objective was not symbolism, but coming up with a nice costume, as a kind of potpourri of costumes that may have been worn at the event by various ladies or maidens, possibly including the queen. In that case, looking for specific symbolism in the portrait, or a symbolic theme, is pointless. One shouldn’t take it too seriously. But, that is not a unanimously held opinion.

Taking the symbolism seriously, I pose what I believe is a simple, and I think, critical question that no one is asking. Why isn’t Elizabeth wearing the hat of the virgin, Virgo Thessalonicensis? That would have been taken from figure 9:

Sorry that the image is a bit blurry. The two hats are similar but it is unmistakable that the one Elizabeth is wearing is the bridal version. I ask the question again: why is a virgin wearing a bride’s hat? Ignoring my question, Erler continues:

Yates, in demonstrating the Sponsa Thessalonicensis’s headdress was the source of Elizabeth’s in the Rainbow Portrait, reprinted only the figure on the left side of the plate. It seems likely, however, that it is the plates’ presentation of three female figures grouped together which caught the eye of the Cecil entertainment’s designer—three figures who correspond closely with the three women of Davies’ poem performed for that occasion.[31]

Okay. Davies’ Contention has a virgin, a wife, and widow. Boissard’s engraving has a virgin, a bride, and a woman, presumably a wife. For Davies’ purposes, a bride would have been out of place. So the widow is a reasonable replacement. Could the three women in Davies’ poem represent the three women in the engraving more or less? They could, but there are many more engravings, each with three figures, many with similarities, and frankly, upon close observation, I do not see how Erler justifies her claim that these “three figures…closely correspond with the three women of Davies’ poem”. There are too many variables and to many other plates with similarities. To justify such a statement I think she would need to closely examine and consider the other figures in the other engravings. And I hope it is not lost on the reader that what Erler is proposing is about 99 percent speculation. However, the point is that, having resorted to mishmash symbolism, Erler can ignore the oxymoron of a virgin queen wearing a bridal headdress. She says:

To the engraving’s headdress he has added a crown and a crescent jewel, the former symbolic of Elizabeth’s rule (and perhaps of Davies’s virgin victory), the latter symbolic of virginity.

I have no problem with the symbols of virginity and the crown on the head of a ‘virgin queen’. I have a problem with the fact that the hat is a bridal headdress. If we are going to construe the symbolism to be important, I think we ought to be consistent. Seeking to tighten the connection of Davies’ poem to the Boissard engraving, Erler says:

Davies’s “Contention” refers to the regal emblem thus:

…on all true virgins at their birth

Nature hath set a crown of excellence,

That all the wives and widows of the earth

Should geve them place, and doe them reverence [Lines 21-24) [32]

Indeed. A crown. On the head of a queen! What a rare idea! There is, I think, some degree of inevitability in that. But, I am not insisting there is no connection between the portrait and Davies’ poem. There may well have been. As a means of ensuring that everyone was comfortable with that Trojan Horse of a portrait, there had to be a cover story. I suspect that Oxford and Davies collaborated. What bothers me is the loosy-goosy handling of symbolism and the facts by ‘professional scholars’. So, what about the bridal hat? Not content to simply cloud the symbolic waters, Erler goes all in to muddy them, throwing in other examples from Boissard’s book:

In addition to the plate, three others in Boissard’s Habitus present a figure labeled “Nova Nupta,” or bride. Plates 5 and 6 show a Venetian bride; the former of these resembles the Rainbow Portrait slightly in its use of pearl jewelry and its gauzy, figure-enclosing veil….The décolletage of all three Roman figures, and the transparent enveloping veil which “Nova Nupta” and “Foemina” wear, are similarly found in the [Rainbow] portrait. … if the Roman bride is viewed in reverse, the similarity of posture becomes more striking; here the position of the lower hand, the gathering the drapery, is identical with that of the Rainbow Portrait.[33]

Here’s the figure Erler is referring to, and again the Rainbow Portrait for comparison (figure 10):

I have reversed the figure on the left as Erler proposed.

Here’s the full plate (figure 11):

Erler says:

Yates suggested that “the clue to [the Rainbow Portrait] may be that it records Elizabeth’s presence at some masque in which allegories in her honour were presented by various personages but which are now summed up in a composite portrait of herself.” Davies’ poem, combined with Boissard’s Thessalonian and Roman designs, provide the particulars which flesh out this hypothesis.[34]

Similarities and composite, hybrid, symbolism? Pick anything you want from the smorgasboard of Boissard’s book and match it up with Davies cliché-rich poem and there is no need, and no point, in debating the “particulars”, as Erler calls them. It is the very essence of academic discussion. Swirling ambiguities. Erler sweeps away all the problems of symbolic meaning. We could go on about the hat, but let’s move on.

Eyes and Ears, and Mouths?

Again, the most obvious and difficult thing to explain about the portrait are the eye and ears, and most especially the mouths. Everyone agrees there are eyes and ears. But are there mouths? Let’s start there. (figure 12)

Are those folds mouths, or are they just folds? As I said, the scholars are confidently divided. Based on my informal survey, opinion divides up as follows:

Pro mouth: 1) Frances Yates (undecided); 2) René Graziani; 3) Christopher Pye; 4) Susan Doran; 5) Raymond L. Lee; 6) Alistair Fraser; 7) Valerie Traub; 8) Daniel Fischlin

Contra mouth: 1) Mary C. Erler; 2) Roy Strong; 3) Michael Neill; 4) Frederick Kiefer; 5) Anna Whitelock;

By the way, Wikipedia cites only Strong and doesn’t mention mouths.[35] I don’t claim to have polled everyone. I hope I have them sorted correctly. If not, I apologize. This should suffice for now. Anyway, there is no consensus among the experts. Roy Strong is perhaps the best known clearly contra-mouth expert. I quote him again (underline added):

A detailed examination of this garment shows no signs of the mouths read into it by scholars [a reference mainly to Frances Yates] so that it could signify the Queen’s fame ‘flying rapidly through the world, spoken of by many mouths, seen and heard by many eyes and ears’. [36]

Strong’s claim is clear and ex cathedra, “A detailed examination”. By whom? How “detailed”? By what method? Since Strong offers no information, I assume the “detailed examination” was conducted by Strong himself by looking closely at the portrait. His principal argument is that the eyes and ears symbolize Fame, or should. He reasons that mouths would reinforce that interpretation, but he ran into trouble when he went to match up the eyes, ears, and mouths with the iconological precedents. To be consistent with the iconographic precedents, he rules out mouths which allowed him to not see them. Trying to assist, Frederick Kiefer says:

In the portrait the queen herself has indeed come to embody Fame. Ironically, Roy Strong himself, whose work is cited by everyone who discusses the Rainbow Portrait, acknowledged, almost twenty-five years before he published Gloriana, the connection with Fame, though he mistakenly thought that the presence of mouths would clinch the identification: “The cloak which encircles Elizabeth is covered with eyes and ears and is probably intended for Fame (although strictly speaking there should also be mouths).” [37]

These two ‘professional scholars’, Strong and Kiefer, are both grossly mistaken. The iconographic representations of Fame do not, as a rule, exhibit mouths or eyes or ears! Here is the figure for Fame from the 1709 English translation of Cesare Ripa’s Iconologia which is essentially unchanged from the earlier editions of Ripa’s book (figure 13):

No eyes, no ears, no mouths. In fact, Fame is typically depicted with the ‘wings of Mercury’ (as we see here) and often with a trumpet. Here’s the description that goes with Ripa’s Fame figure (figure 14):

We see, not surprisingly, that speech and voice are associated with Fame while they are not part of the graphic symbolism in the available precedents. Inexplicably, Kiefer says:

In fact, Renaissance Fame is never decorated with mouths, only eyes, ears, and sometimes, tongues, as hundreds of prints and other representations demonstrate.[38]

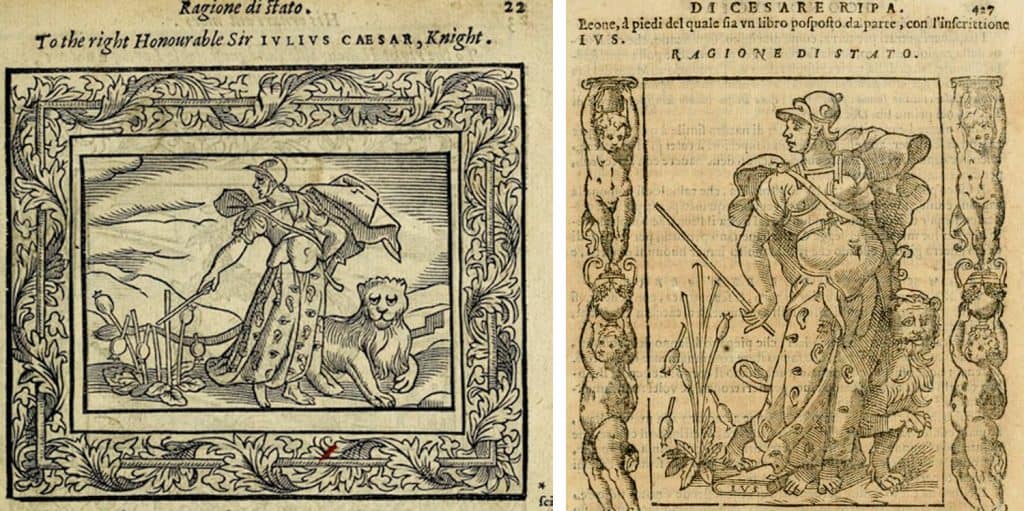

Where is Kiefer getting his information? Not from Ripa’s Fame. Fame is not depicted with eyes, ears, or tongues. Kiefer is similarly contradicted by the Encyclopedia of Comparative Iconography: Themes Depicted in Works of Art.[39] How did Kiefer and Strong manage to be so completely wrong on something so completely obvious? Simple. While seeming to talk about Fame, they switch to a different figure. Strong says:

The symbolism of the cloak in fact presents no problems. Henry Peacham has just such a garment in one of the emblems in his Minerva Britanna (1612); it is worn by Ragione de Stato and is in fact lifted directly from Ripa’s Iconologia.

Be serv’d with eies, and listening ears of those,

Who can from all partes give intelligence

To gall his foe, or timely to prevent

At home his malice, and intendiment.[40]

Now Strong is suddenly talking about a figure called Reasons of State. Here is that figure from Peacham’s Minerva Britanna (figure 15):

‘174 Ragione di stato wearing a robe covered with eyes and ears’

Eyes and ears, and no mouths, on the wrong figure! So, Strong has the wrong figure and, please note, fails to observe that these eyes and ears are on the outside of the garment. What does Peacham’s figure of Ragione di stato have to do with the Rainbow Portrait? Nothing! Minerva Britanna wasn’t published until 1612, ten or twelve years after the painting was painted. But, it will be instructive to stay for a moment with the unrelated figure Ragione de stato and Ripa’s Iconologia from which Peacham almost certainly borrowed in 1612. According to Wikipedia:

The first edition of his Iconologia was published without illustrations in 1593 …A second edition was published in Rome in 1603 this time with 684 concepts and 151 woodcuts …The book was extremely influential in the 17th and 18th centuries and was quoted extensively in various art forms. [41]

Here is an image of the cover of Iconologia bearing the 1603 date (figure 16):

https://archive.org/details/iconologiaouerod00ripa/page/n3

Below is a side-by-side comparison of Ragione di Stato (Reason of State) in the Peacham and Ripa versions (figure 17):

We see that Peacham’s version was faithful to the Ripa version. To be safe, let’s go ahead and take a look at Ragione di Stato (Reason of State) from the 1709 English version (figure 18):[42]

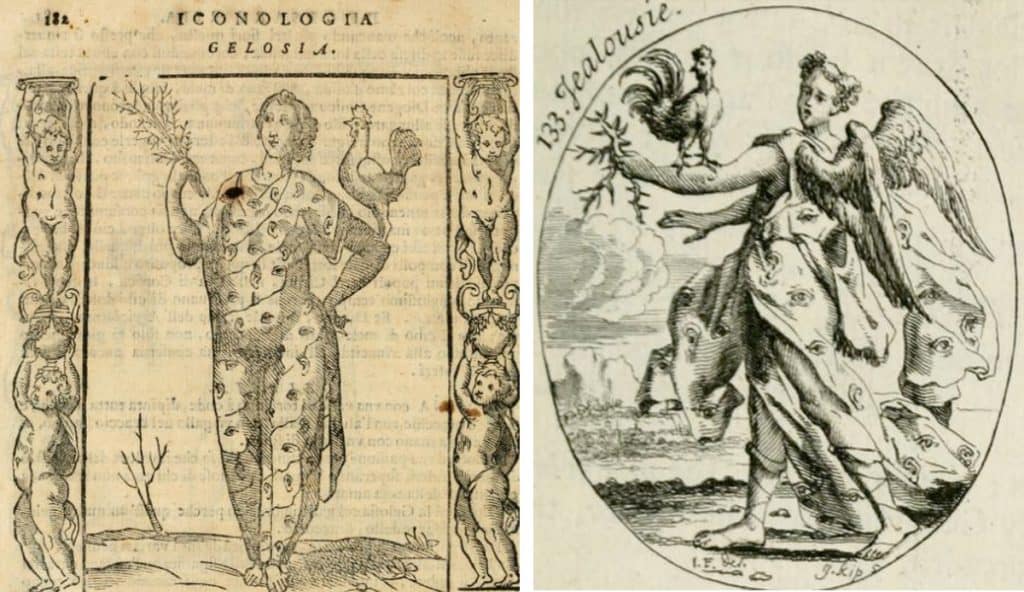

The symbolic elements are essentially the same in all three versions with eyes and ears on the outer surface of the skirt. Now, having mysteriously slipped Ragione di stato in place of Fame, Strong also neglects to mention that, in Ripa’s Iconologia, there are three other figures with similar eye and ear symbolism. They are: Gelosia (Jealousy); Curiosita (Curiosity); and Spia (the Spy). For the figures of Curiosita and Spia, Ripa (1603) provides only descriptions and no drawings. Here is Gelosia from 1603 version (left) and the 1709 version (right) (figure 19):

Eyes and ears are normal features for this figure. Below is the 1709 English version of Curiosity (figure 20):[43]

Again, eyes and ears. To the right is the figure Spia (the Spy) from the 1709 version (figure 21):

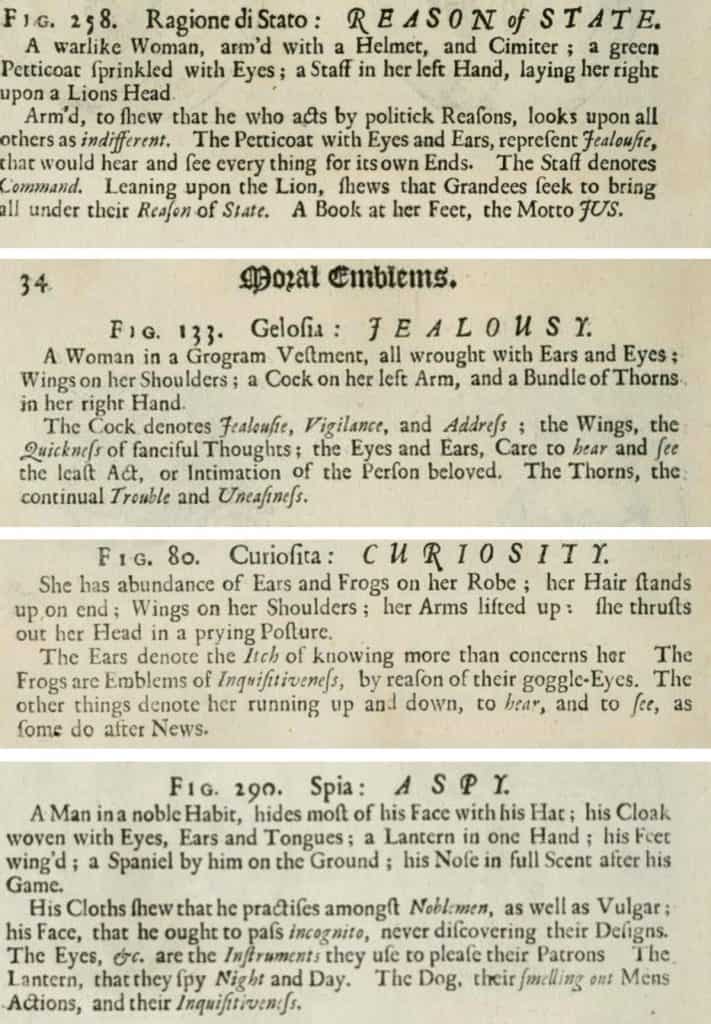

Again, eyes and ears and, though hard to make out, tongues. Since it is difficult to see the detail in these printed figures, let’s look at the accompanying descriptions for all four figures. The following descriptions are from the 1709 English version (figure 22):

Here is my summary of the symbolic features from each of these figures:

- The State: Eyes and ears represent Jealousie that would hear and see everything for its own ends.

- Jealousy: Eyes and ears care to hear and see the least act or limitation of the person beloved.

- Curiosity (excess curiosity): Ears denote the itch of knowing more than concerns her.

- A Spy: The eyes, ears, and tongues are instruments they use to please their employer.

Perhaps we can agree that tongues and mouths serve the same symbolic purpose. In that case, the figure that comes closest to the symbolism in the Rainbow Portrait is Spia, the Spy, and that, I think most people will agree, is not a quality an ostensibly benign ruler would advertise. But then again, none of these figures represents desirable qualities in a ruler from the perspective of the subject or citizen; and though none of these scholars is willing to call a spade a spade, this is the central problem in trying to explain the eyes, ears, and mouths in the liner of the cloak in the Rainbow Portrait. They just don’t seem benign.

Therefore, intuitively, Fame seems like a good explanation. The problem is that you have to ignore the iconographic precedents. So, to recap. The five iconographic figures we’ve considered that have eyes and ears are not benign (with the possible exception of Curiosity). Fame, which would be benign, has no eyes or ears and no mouths. It’s a conundrum. And the problem remains, as I keep pointing out—and as none of these scholars do—that the eyes and ears and mouths in the Rainbow Portrait are on the inside of the garment. Trust me, we will come back to that again. Let’s dig deeper into the mouths.

Mouths or Folds?

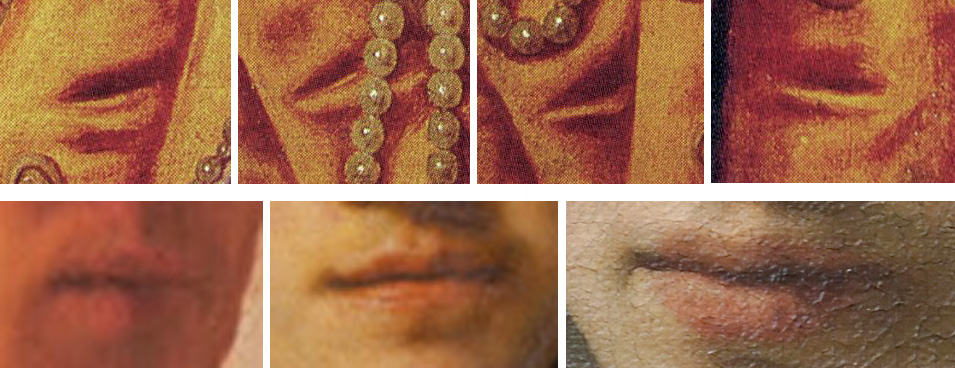

Let us go back to Roy Strong’s strong assertion that “detailed examination of this garment shows no signs of the mouths”. How was that determination made? There’s no indication that he consulted anyone. Who would count as an authority? A portrait artist? I don’t think so. Someone experienced in period costume design? Perhaps. But, let’s approach this analytically. The thing about the mouths, compared to the eyes and ears, is that they are ambiguous. The eyes and ears are well defined. The mouths are merely suggested. Why? Below (on the top row) are some close-ups of the Rainbow Portrait. In the row underneath, for comparison, are close-ups of mouths painted by Rembrandt (figure 23):

Pardon if they are a bit dark or blurry. The point is: if the painter of the Rainbow Portrait had wanted mouths to be unambiguous, he could have made them unambiguous. So, by simple visual inspection, we cannot determine that the mouth-like folds are intended to be mouths. However, nor can we determine that they are not meant to suggest mouths, as claimed by Strong. Nor can we rule either way on the suggestion by Traub and Fischlin, et al., that the folds represent vaginas. Are there any experts who can help sort this out? I think there are. But we have to turn the question around. The question is not whether the mouth-like folds are mouths, but whether the mouth-like folds are folds. If they are not folds, they are, by default, almost certainly mouths (and possibly vaginas). But, noting that the preponderance of scholarly opinion seems to fall on the side of the folds being mouths, perhaps that is sufficient for our purpose here.

There is some additional evidence that may help advance this discussion, and which, I think, confirms that Marcus Gheeraerts was, in fact, the painter of the Rainbow Portrait. The portrait below was painted by Gheeraerts (so indicated by his signature) and is dated to 1611, roughly ten years after the Rainbow Portrait. I place it side by side with Rainbow Portrait (figure 24):

I must note that, in the Hertford, the orange-gold fabric is on the outside of the garment (which looks like a tablecloth). The grey on the reverse side is effectively on the inside. Based on the positioning of the folded fabric around the lady’s right hip, the floral embroidery on the bodice, the fine lace along the edge of the bosom and in the collar, the treatment of the bosom, the positioning of the body and head and the facial expression, I think we might agree that the portrait of Lady Hertford was intended to resemble the Rainbow Portrait. I think that those who have some familiarity with painting technique will also agree that these two portraits are very likely by the same artist. Not seen or intimated on the draped fabric of the Hertford Portrait is any suggestion of eyes, ears, or mouths on the fabric. There are a couple of curious little creases. Let’s look more closely (figure 25):

I count three little creases on the Hertford. I do not believe that, even if led in that direction, anyone viewing this portrait would suspect that those little creases are mouths. They are not ambiguous. In our comparison of these two portraits we see just how distinctly mouth-like the folds in the Rainbow Portrait are. I think we have multiple substantial reasons to question Roy Strong’s “detailed examination”. Perhaps someone would like to attempt an edit at Wikipedia and cite some other sources.

Failed Explanations for the Eyes and Ears and Mouths

Roy Strong, evidently in desperation, reached forward through time to Peacham’s Minerva Britanna of 1612 to explain the eyes and ears that appeared in 1600-1602 in the Rainbow Portrait. And, without knowing it, he reached as far backward through time again. Strong says:

Peacham is using the ears and eyes in the same way John Davies refers to the Queen’s use of her servants (of whom Cecil was chief) in his first entertainment in 1600: ‘many things she sees and hears through them, but the Judgment and Election are her own’.[44]

To what is Strong referring? He is referring to another little script written by John Davies, this one called, A conference between a gentle-man usher and a post (messenger) before the Queen at Mr. Secretary’s house. Therein we find the bit of dialogue Strong refers to, and from which I will quote again momentarily. The ‘Post’ (messenger) bears letters from the emperor of China. Protocol requires that they be delivered to the queen’s secretary. The usher advises that the secretary is not available and that the messenger can deliver the messages directly to the queen herself. The messenger is startled by the advice and is intent on following protocol. The usher insists. He says:

Usher: I know not what you think, but I am sure the world thinks she [the queen] doth herself best service when all is done, for all her morose servants; though I confess (for honour’s sake) all great princes must have attendants for their business.

What the usher means is that the queen is a practical person and prefers that things ‘get done’ without excessive deference to protocol, even if there are many servants attending her. To which the messenger replies:

Messenger: Is it so? Why, then, I pray thee, tell me what use doth she make of her servants.

The messenger’s point is: Why then have all those servants? And the usher replies:

Usher: Many things she sees and hears through them, but the judgement and election is her own.

It seems to me that the usher’s reply is incongruous, but, for our purpose here, I don’t think that’s important. Let’s follow along a bit further:

Messenger: If, then, the use of their service is so small, how come it that the reward of their service is so great?

Usher: Oh, therein she respecteth her own greatness and goodness, which must needs be such as it is, though I find no object that is proportionable: as, for example, the sun doth cast his beams upon dark and gross bodies that are not alike capable of his light, as well as upon clear and transparent bodies which do more multiply his beams. Or if thou dost not understand this demonstration, I will give thee one that is more familiar. She doth in this resemble some gentle mistress of children, who, when they guide the hands of their scholars with their own hands, and thereby to make them write fair letters, do yet to encourage them and give them as much praise as if themselves had done it without direction.

In other words, the queen is patient and magnanimous with her servants and subjects. Now, according to Strong (and he’s not alone), in the line below, which Strong made reference to, is what is symbolized in the eyes and ears, and possibly the mouths, on the liner of the cloak in the Rainbow Portrait:

Usher: Many things she sees and hears through them, but the judgement and election is her own.

And why not? Well, let’s double check the facts. According to Strong, this little dialogue, written by Davies, was presented for the queen’s pleasure in 1600. Edmund Chambers, and a number of other scholars, slightly disagree, dating it to 1602. No big deal. But, actually, there is a big deal here. According to John Nichols’ transcriptions from the royal archives (1823), the date of the presentation of A Conference was 1591.[45] He’s very clear. Here’s a little snippet from Nichols’ book (annotated circle is on the original this was snipped from) (figure 26):

The entry that follows the one above is without date, but says:

On the second of August Sir Robert Cecil was sworn of the Privy Council at Nonsuch.

The date of Robert Cecil’s appointment to the Privy Council was 1593. Sequentially at least, the two records fit. And we have a corroborating account from Charles Knight from 1893:

Progresses of queen Elizabeth No. XI.-1587-1591. “In 1591…A conference between a gentleman-usher and a post…written by John Davies”. [46]

Knight provides no source for his information though it appears to be taken from official records. Notably, overruling Nichols and Knight, the esteemed Edmund Chambers dates A Conference to 1602. He reasons:

Nichols, Elis. iii. 77, prints from Harl. MS. 286, f.248, ‘A conference between a Gent. Huisher and a Poet, before the Queen, at Mr. Secretaryes House. By John Davies.’ He assigns it to 1591, but Cecil was not then Secretary, and it probably belongs to 1602. [47]

Mary C. Erler makes the same case:

Davies wrote another dialogue for presentation before Elizabeth, this one prose. …Since it is undated, Nichols place the work among his documents for 1591, thus assigning it to Cecil’s entertainment of the queen at Theobalds from May 10 to May 20 in that year. R. W. Bond points out, however, that Robert Cecil did not become Secretary until 1596, and both he and E. K. Chambers assign the work to Cecil’s entertainment of December 6, 1602.[48]

One will be very careful in overruling Edmund Chambers, but he is wrong in this case, and so are Bond and Erler. First of all, there is no factual reason to suppose that Nichols, lacking a date, arbitrarily assigned Davies’ Conference to the location of Theobalds. But, much more importantly, William Cecil was, in fact, Secretary of State in 1591. Francis Walsingham, Secretary of State, died in 1590. William Cecil temporarily added those duties to his own and served as ‘acting Secretary of State’ from 5 July 1590 – July 1596.[49] Thus, during that time period William Cecil was concurrently Lord High Treasurer and Secretary of State. It stands to reason that a messenger would seek to deliver letters to the ‘Secretary’ and not the ‘Lord High Treasurer’. Following standard protocol he asked for the ‘Secretary’. Following the errors of Chambers and Bond and Erler, evidently adding another, Martin Wiggins and Catherine Teresa Richardson also date A Conference to 1602. They say:

The case for identifying the dialog as part of the 1602 Cecil House entertainment depends on the hypothesis that Manningham’s account misreports the origin of the post. [50]

I have scoured Manningham’s Diary and cannot find any mention of Davies’ ‘dialog’ or ‘Conference’ therein. In the versions reported by Nichol and Knight, the letters are from ‘the emperor of China’. I’ve not found any version with a different ‘origin’. To be fair, the accuracy of Nichols’ transcriptions has been challenged on numerous counts. Another reason put forward to doubt Nichols in this case is that, in 1591, Davies was not yet sufficiently experienced and recognized as a poet to have served in that capacity for such an occasion. This is sheer uninformed speculation. Davies was born in 1569. He would have been twenty-two years old in 1591. John Milton was twenty-years old when he wrote his ‘Epitaph on Shakespeare’ that was included in the Second Shakespeare Folio.[51] The following is from the current Wikipedia article on John Davies:

He was educated at Winchester College for four years, a period in which he showed much interest in literature. He studied there until the age of sixteen and went to further his education at the Queen’s College, Oxford, where he stayed for a mere eighteen months, with most historians questioning whether he received a degree. Davies spent some time at New Inn after his departure from Oxford, and it was at this point that he decided to pursue a career in law. In 1588 he enrolled in the Middle Temple., where he did well academically, although suffering constant reprimands for his behaviour.[52]

The evidence indicates that Davies was present in London in 1591. A Conference is not regarded as a good example of Davies’ talent as a poet (to which I add my humble concurrence) and fits, qualitatively, with his early work. So, while A Conference can be construed to fit the portrait (along with countless other poems and dialogues), the documentary evidence (which is not contradicted by any factual evidence), places A Conference firmly in 1591, ten years earlier.

I apologize that this has gotten to be a bit complex; however (and this is important), as convenient as it might be as an explanation for the eyes and ears and mouths on the cloak liner, John Davies’ Conference turns out to be quite implausible. So, where are we? What else have the scholars come up with to explain those discomfiting eyes and ears and mouths? Christa Wilson puts it so:

…the cloak’s eyes and ears provide more ambiguous and inventive means of conveying Elizabeth’s unearthly insight and power. Signifying that Elizabeth sees and hears all throughout her realm …[53]

Now, think about that. It’s not that it’s absolutely implausible; it just highly improbable, in my opinion, that someone clever enough to devise this portrait would go to all that trouble to convey the message that Elizabeth was a snooping all-seeing all-hearing demigod. Were there no limits to what the average Englishman was expected to believe and tolerate? It’s not as though Wilson is completely blind to the problem. She continues:

Furthermore, by instilling a “disquieting suggestion of …governmental surveillance,” they likewise convey Elizabeth’s ability to detect and expunge both external and internal threats to her power, thus placing her above and beyond the realm of vulnerability to which the even the greatest of mere earthly princes would otherwise be subject (Frye 103).[54]

I think that, at the time, among the people of England, there was a kind of understanding that the queen’s ‘virgin queen/faerie queen’, persona was more a political expediency than reality. To put it another way, it’s like grown-ups today, and many children, treating Santa Claus as a real person while being pretty sure he isn’t. I don’t think that Elizabethan Englishmen, and English women, were stupid. I think Robert Cecil understood that there were limits to what the persona cult would tolerate. Placing Elizabeth above ‘earthly princes’, advertising her as a demigod who was ‘beyond the realm of vulnerability’ would, in my opinion, have gone too far. I think there are limits to what Elizabethans were willing to believe. Among professional Elizabethan scholars I see no limits. I am half jesting.

The Hidden Meaning of the Rainbow Portrait

For the Rainbow Portrait there are three primary points of contention: the colorless rainbow (and inscription); the eye, ears, and mouths; and the hat. What does the rainbow (and the inscription or ‘motto’) mean; why is the rainbow colorless; and why is it shaped like a tube? There are several different scholarly explanations for the missing color. The first is that the original pigment has faded. As a number of scholars have conceded, this is improbable. The colors in the portrait are too vibrant. If the rainbow had been colored, some color would remain on the rainbow. And, as several of those scholars have conceded, the rainbow is shaped like a tube. In explaining the rainbow and the inscription (as with the eyes and ears and mouths) there has been lots of stumbling around. Take Graziani’s attempt to explain the ‘motto’:

If the portrait’s motto in any sense intends the Queen as the rainbow, it makes the point that she can appear only because there is a sun.[55]

Did Graziani misspeak? How does that work? Does that mean that, when it is nighttime or cloudy, Elizabeth is not the queen? Or, she’s only queen when the sun comes out or up? Or does it mean that she is queen because there is a sun that circles the earth? It doesn’t make any sense to me. However, the motto makes perfect sense to me if I treat the inscription as a riddle, and, by way of a homophone, replace ‘sun’ with ‘son’. Thus corrected, Graziani’s statement would be:

…that she can appear [as a rainbow] only because there is a son.

Pretty clear. Who’s the son? But of course, if Elizabeth was a virgin, there was no son. The essential message of the portrait, I say, is actually quite simple. It tells us Elizabeth was not a virgin and that there was a son. In fact, if we pay close attention, it tells us that Elizabeth had three royal heirs (yes, three!), corresponding to three strands of hair (homophone heirs) descending onto her shoulder and breast, tending to the general location where a babe would be nursed. The portrait redundantly conveys this message, with special emphasis on the fact that she was, in fact, not a virgin. The eyes, ears, and mouths on the inside of a cloak of secrecy, where they would not normally be seen, symbolize the forced invisibility of these royal heirs (and their children). Those royal heirs see and hear and speak (to a point) but their royal identities are concealed behind the cloak of secrecy.

So, this symbolism is actually quite simple and straightforward as is the meaning of the motto. Had Elizabeth acknowledged her son, he would have colored her rainbow, both in the painting and in what he would have written about her. That, and her children and grandchildren, would have carried on her legacy; a legacy that was not the hypocritical lie of her highly advertised virginity. Included in this is the prospect that Oxford would have become king, though I think he considered that a long-shot.

I must digress slightly. Based on my interpretation of Amoretti,[56] just before Henry’s Wriothesley’s birth, Oxford and the third royal sibling (a sister) offered to renounce their secret claims to the throne and remain forever hidden if Elizabeth would acknowledge Henry, who was the youngest of the three. Importantly, Elizabeth could claim to have been a virgin at the time she took the throne. It seems she was tempted, but declined. Oxford was extremely disappointed and went AWOL. That was June-July 1574. His AWOL is a matter of record. Yes, I’m saying Henry was not born on 6 October 1573 as is recorded. He was born on Ascension Day, 31 May, 1574. The death of Mary (Brown) Wriothesley’s infant son (my theory), provided a perfect place to hide the latest royal sibling.

I believe that, for Oxford, that offer remained the best option until Henry got caught up in the Essex rebellion. That was the climactic end of plan A. But Oxford could not give up hope. Elizabeth could, even on her deathbed, acknowledge him. True, he didn’t have the best reputation among the peerage, but who did? Oxford was a Tudor and he was English. To many that might have seemed preferable to turning England over to a man who wasn’t even English, whose own mother had been executed by order of Queen Elizabeth and her counselors, and was already a rumored homosexual with bizarre fixation on witches and black magic. That son a ‘murdered’ queen might have held a grudge and who knows where that might have led. I am speaking, of course, of James VI of Scotland who became James I of England. I think many would agree that that didn’t work out all that well.

It has been argued by Prince Tudor theorists that, based on the Treasons Act of 1571,[57] a “natural” but ‘unlawful’ child (bastard) of Queen Elizabeth could have ascended to the throne as Elizabeth’s successor. The relevant portion of the Act says (underline added),

Whosoever shall hereafter … declare … at any time before the same be by Act of Parliament of this Realm, established and affirmed, that any one person … is or ought to be the right Heir & Successor to … the Queen’s Majesty … except the same be the natural issue of her Majesty’s Body … shall for the first Offence suffer imprisonment ….

Thomas Regnier makes a persuasive argument that, on the basis of ‘common’ and ‘ecclesiastical law’, precedent stood firmly, perhaps impenetrably, against this proposition.[58] I do recommend Regnier’s essay, and I think he is correct on the ‘law’, but I think there is more to the story. It seems improbable to me that the words “natural issue” were simply ill-chosen, as if someone wasn’t paying attention. As Regnier points out, the words “natural issue” were contemporaneously construed to mean ‘bastard’ and that did prove to be a problem. Regnier quotes William Camden (comments and underline added):

But incredible it is what jests lewd catchers of words made among themselves by occasion of the Clause [referring to the words “natural issue” in the Act of 1571], Except the same be the Natural issue of her body; forasmuch as the Lawyers term those Children natural, which are begotten out of Wed-lock [i.e. ‘bastards’] . . .[59]

Camden was the quasi-official historian of the Elizabethan regime (plainly stated, a member of the Elizabeth-Cecil propaganda machine).[60] It is interesting that he saw it necessary to bring the matter up, thus drawing more attention to it. By the time he did the reign of the Tudors was over and the point was mute. And that’s not the only evidence of that phrase being a problem. Regnier says: