Six Shaky Signatures

Six Shaky Signatures: What’s the Proof That Shakespeare Wrote Them?

By: Dorothea Dickerman

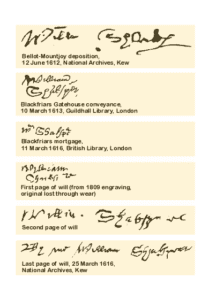

What if the famous man from Stratford-upon-Avon commonly thought to be the greatest English playwright and poet was in fact unable even to form the letters to write his own name, much less write the Shakespeare Canon? After 400 years of extensive searching, no play, poem, note, draft or letter in his hand writing has been found. Over the centuries, hundreds of “Shakespeare’s” alleged signatures have been debunked as forgeries. What remains are six poorly scrawled versions of Will of Stratford’s name (let’s call him “Will of Stratford” to avoid confusion with the writer “Shakespeare”, who may have been using a pseudonym). The signatures appear, some with wax seals attached, on four legal documents written by others: a 1612 deposition in the Bellott-Mountjoy case, a 1613 deed and mortgage for the Blackfriars Gatehouse purchase, and his 1616 will. These signatures span just four years at the end of Will of Stratford’s life. There exists no “Shakespeare” signature from the playwright’s most active period. Traditional scholars cling to the conclusion that these differently spelled and inconsistent signatures prove Will of Stratford could hold a quill, sign his name and write the works of William Shakespeare.

Matt Hutchinson’s article, “ The Slippery Slope of Shakespeare’s ‘Signatures’”, published in The Oxfordian, vol. 23, p. 1-99 (2021), however, argues otherwise. He shows that the existence of these six signatures is far from definitive proof that Will of Stratford could write his name or anything else. In fact, when the exact wording of the legal documents that bear them is examined in the context of then-contemporaneous English law, they tend to prove the contrary. Images of the purported original signatures can be found in Hutchinson’s article as follows: page 86, figures 6, 7; page 87, figure 8.

Many scholars and casual observers have remarked on the material differences among each of the first five signatures and that only the 5th and 6th appear to be in the same hand. Over the span of four years either his signature changed rapidly and substantially five times, or others signed his name for him more than once on legal documents. How do we know whether Will of Stratford alone actually held the pen that made any of the six signatures? If any or all of the signatures were not his, who signed for him and why? What are the implications of disproving the authenticity of these signatures on the Shakespeare Authorship Question?

While it is obvious that any literate person can physically sign someone else’s name, in Elizabethan England it was legal and necessary for certain people to make valid and binding legal documents without actually signing their own name. Hutchinson corrects the commonly-held but mistaken modern assumptions about how Elizabethan law met the legal needs of a society where, outside of the nobility and clergy, perhaps 3 of 10 men and 1 of 10 women were literate. By examining early 17th century English law’s requirements and the wording of each of those four legal documents, Hutchinson explains that it is overwhelmingly likely that legal clerks made all six signatures attributed to Will of Stratford.

Literate Elizabethans in all walks of life developed elaborate, personalized signatures, carefully forming them into individualized works of art, usually in italic script. Hutchinson contrasts numerous examples of clean, evenly and consistently formed signatures of contemporary playwrights, actors, tradesmen, servants, musicians, lawyers, and testators with the anomaly of the blotted, sloppy and inconsistent purported signatures of Will of Stratford, written, not in italic script, but in secretary hand, a form of early shorthand, which was commonly used by scribes and legal clerks. A further anomaly is the variable spellings and abbreviations of both Will of Stratford’s first and last names, not commonly found among other contemporary signatures. Possible readings of the six signatures are, in chronological order: “Willm Shakp”; “William Shaksper”; “Wm Shakspe”; “William Shakspeare”; “Willm Shakspear”; “By me, William Shakspear”. Not one of them used the full surname “Shake-speare” or “Shakespeare” as found in the Canon.

Unlike Heminges’ and Condell’s claims of Shakespeare’s blotless manuscripts, several of the purported signatures by Will of Stratford contain a noticeable large dot or blob in different locations, none over the “i”s. These dots or blobs can be seen in Hutchinson’s article as follows: page 91, figure 12; page 93, figure 17A; and page 95, figure 19. Hutchinson cites a variety of opinions about the marks’ meaning, including mere ornamentation and a purposefully made “mark” that Will of Stratford used in lieu of a signature he was incapable of making. Hutchinson notes that none of the signatures of the other parties to the documents, nor any of the 130 writers in W. W. Gregg’s 1932 English Literary Autographs, contain such marks, although clerks writing in secretarial hand often used them.

Hutchinson’s examination of the exact wording in each of the four legal documents and the then-applicable law’s requirements overturns both our 21st century assumptions about early 17th century English law and legal practice, and any certainty that Will of Stratford penned any of the signatures.

The Bellott-Mountjoy Deposition. A deposition is a witness’ out-of-court oral testimony under oath transcribed by an authorized legal officer, such as a legal clerk. Early 17th century English law required that depositions be signed either by the witness personally using his or her best efforts at a signature, including full surname, or with his or her usual mark. Given the large spot under the “S” in the abbreviated surname and several scholars’ opinions that the signature is that of a clerk “desir{ing} only to indicate by an abbreviation that the dot or spot was the mark of William Shakespeare of Stratford-upon-Avon”, considerable reasonable doubt is cast on the deposition signature being in Will of Stratford’s hand. Unless he made only the large spot and a law clerk identified it as his mark by writing a portion of his name over the mark, the deposition did not meet the requirements to be legally admissible in court and would have been useless.

The Blackfriars Gatehouse Documents. These documents relate to the acquisition and financing of real property just outside London. A wine merchant named William Johnson, a gentleman named John Jackson and Will of Stratford entered into an agreement to purchase the Blackfriars Gatehouse on March 10, 1613 and the mortgage to pay for it the next day. Four other men witnessed the sealing and delivery of the two documents on their reverse sides, for a total of seven signatures. Of the seven signatures all were identical between the two documents signed one day apart, except (you guessed it), Will of Stratford’s. His name is spelled differently and the signatures appear to be in very different hands, literally from one day to the next.

Hutchinson brings to light that, due to widespread illiteracy, deeds of the era could either include the phrase “set their hands and seals” if all the parties could write their names, or the phrase “set their seals” if some party could not write. For the illiterate, a wax seal was affixed to the document by a strip of parchment threaded through a hole punched in the document, as seen in Hutchinson’s article on page 96, figure 20; and page 97, figure 21. If designated to belong to that individual, it was the legal equivalent of that illiterate person’s signature. Both of the 1613 documents with Will of Stratford’s name on the strip clearly say “set their seals” indicating signatures were not legally necessary. In contrast, the 1618 document transferring the Blackfriars Gatehouse to new owners, signed five years after Will’s death by Johnson, Jackson and John Heminges, reads “Sett their hand and seals”, thus requiring a seal and a signature from each man.

The clerk who drafted the 1613 deed and mortgage accommodated Will of Stratford for some reason. If he had been able to sign his name, the clerk would have written “set their hands and seals”, like the 1618 deed, which was the more secure way to avoid fraud. Was the accommodation made due to Will of Stratford’s disability, inability or unwillingness to sign his name on the 1613 documents? It doesn’t matter. The point is: the signatures above the wax seals in different hands on the Blackfriars Gatehouse deed and mortgage are likely not his, but those of the clerks for the purpose of labelling his seal with his name to authenticate it and avoid confusion. The seal under Will of Stratford’s and Johnson‘s names is the same seal. Hutchinson points out that it belonged to the clerk Henry Lawrence because Will of Stratford and Johnson did not have seals of their own.

The Will. Anomalies also appear in Will of Stratford’s 1616 will, some discovered thanks to the 2016 conservation undertaken by the National Archives:

- Different inks were used in the will at different times.

- None of the will’s four witnesses were present when the testator’s name was written on page 3 in January 1616 (“By me, William Shakspear”), because they signed 3 months later in March 1616 in different ink.

- While the wills of 40 other dramatists or actor contemporaries used by Hutchinson as comparisons all contained the familiar “In the presence of” or “witness hereunto” language still used today to indicate that the witnesses saw the testator physically sign. Will of Stratford’s will said “Witness to the publishing hereof”. Witnessing the “publishing” means that the witnesses did not witness the actual signing of the will but rather that the will was acknowledged before them to be Will of Stratford’s will.

- The law clerk originally set up the will to be sealed only (“In witness whereof I have put my seale”), as though, like Blackfriars Gate house deed and mortgage, Will of Stratford could not sign his name. Later, unlike 135 other wills of the period set up to be sealed only, the word “seale” was stricken and replaced with “hand”.

- Of all six signatures, only those on pages 2 and 3 of the will appear to be in the same hand. The hand that made the signature on page 1 of Will of Stratford’s will is distinctly different.

In 1616, English law required valid wills to be in writing, but because of high illiteracy, did not require the maker to sign in his or her own hand. A valid will was authenticated in one of three ways: (1) being signed by the maker; or (2) bearing a seal (even belonging to someone else); or (3) being signed at the maker’s direction by someone else and acknowledged. After death, wills were proved by the executor’s oath, unless objections arose. Then the witnesses would be examined. Not only did Will of Stratford’s will not have to be signed by law, the witnesses to his will never saw him sign it. They were only witnessing that it had been acknowledged to them to be his will. The fact that the will, a legal document, was signed and witnessed does not prove that the hand holding the pen belonged to Will of Stratford; instead, it tends to prove that he did not personally sign it.

None of the six signatures on the four legal documents can definitively be shown to be in the hand of Will of Stratford. In fact, as Matt Hutchinson has shown, it is likely that all six signatures were legally written by law clerks, even purposefully made in disguised and sloppy hands to clearly signal that the signatures were not those of Will of Stratford, but rather of the clerks themselves doing their jobs in keeping with the law of a society in which the vastly illiterate populace still needed to make depositions, deeds, mortgages and wills. With all the six signatures resting on very shaky ground, if not knocked completely out by Hutchinson, what is left to support the claim that Will of Stratford could wield the pen that wrote the Shakespeare Canon?

Membership dues cover only a fraction of our budget, including all our research, preservation and programming. Please support the SOF by making a gift today!

Blue Boar Tavern: Wassail Q&A

Tuesday Dec. 17, 8pm E / 5pm P

Sign up below for event invites!