by John Hamill

Originally published in The Oxfordian, v. 8, pp. 25–59 (2005) (repaginated PDF version here); republished on the SOF website Nov. 8, 2017, updated 2021.

In Shakespeare, whose works deal with every aspect of human life, we would expect to see much about sex, and indeed we do. Everything he wrote deals with it in some way. Even to events and relationships that are not inherently sexual he gives sexual overtones, or allows them to be so interpreted by his actors and directors. As the English poet laureate, John Masefield wrote, “Sex ran in him like the sea.” Few would argue with this. But what exactly do his plays, poems, and sonnets tell us about Shakespeare’s own sexuality, and what role does it play in the on-going Shakespeare authorship challenge?

J.T. Looney’s ground-breaking book “Shakespeare” Identified (1920) began the modern era of the authorship controversy by analyzing Shakespeare’s works for clues to the author’s true identity. With surprising ease he found that it was Edward de Vere, the seventeenth Earl of Oxford, who reflected, not just some, but all the eighteen qualities suggested by the works. One, however, was less than fully explored: Shakespeare’s “doubtful and somewhat conflicted attitude to woman”; despite the fact that, as Looney claimed, this one characteristic might “afford an explanation for the very existence of the Shakespeare mystery” (103, 118–19).

Joseph Sobran, in his Alias Shakespeare (1997), was not the first to point out Shakespeare’s homoeroticism, but he was the first to connect it to apparent homosexual behavior in the biography of the Earl of Oxford. Yet, despite Sobran, few Oxfordians seem to understand either its importance or how it supports Oxford’s case for the authorship. Orthodox Shakespeare scholars are just as hesitant. As Maurice Charney states, “The issues of the homoerotic in Shakespeare are hopelessly entwined in academic controversy. Everything seems to come back to the unanswerable question of Shakespeare’s own sexual orientation” (159). With Oxford as Shakespeare, “the question” is no longer unanswerable.

Homosexuality in Renaissance England

Since the 1960s a new wave of feminist and “queer theory” literary criticism has been redefining the traditional straight male interpretations of literary history. Since then, scholars such as Alan Bray, Bruce R. Smith, and Charles Summers have been providing us with extensive and definitive research into early modern views on sexuality. For instance, nobody thought of themselves as “gay” in the sixteenth century. The term homosexual did not exist until a distinct homosexual subculture developed in the late nineteenth century (Smith Desire 11–12).

This of course does not mean that homoerotic feelings and behavior did not exist until the nineteenth century. Evidence of homosexual desires and behavior are to be found in every culture on earth and at every time and place in history — most obviously among our cultural ancestors, the ancient Greeks, for whom it was a prominent cultural feature. But even in cultures where it was not officially accepted, it has often been tolerated as a secondary form of human sexuality. In the sixteenth century, the more tolerant attitudes towards all forms of sexual behavior that had characterized pagan and medieval Catholic cultures were undergoing a process of reversal by the rigid moral standards of the Protestant Reformation.

The closest that early modern English comes to a term for homosexuality is sodomy. But to the Elizabethans, sodomy was solely an act; it was not a lifestyle. In other words, if a man committed an act of sodomy, what he did was called buggering and the participants were not considered to be anything other than ordinary men who had committed the crime of buggery. The concept of being a homosexual, that is, of homosexuality as a permanent condition, did not yet exist (DiGangi Drama 4). In addition, the term sodomy was not specific to anal intercourse, as it is today, but was a general term for a variety of socially taboo acts categorized as general “debauched behavior,” including buggery, sorcery, heresy, bestiality, Papism, and treason both to the monarchy and to God (Bray 16–28).

In England, perceptions of homosexual behavior during the period in question went from a minor sin, one that could be absolved by confessing to a priest, to a criminal act, the most “detestable abominable sin amongst Christians, not to be named” (Coke 38). As Alan Bray puts it, “it is difficult to exaggerate the fear and loathing of homosexuality to be read in the literature of the time” (62). The mere accusation was enough to destroy a man’s honor and social standing.

Henry VIII, in his efforts to seize wealth and power from the Church, created the first anti-sodomy law as part of a whole panoply of legislation attacking the Roman Catholic Church and passed by the Reformation Parliament of 1533–1534 — a law revoked under his daughter, the Catholic Mary Tudor. Her Protestant sister, Queen Elizabeth, made sodomy a felony again under a statute passed by Parliament in 1562–1563, this time punishable by death (Crompton 362–366). (The concept of homosexual intercourse between women did not yet exist.)

For these and other reasons, most literary works involving same-sex attraction were not openly published. With the exception of a few texts such as Christopher Marlowe’s Edward II (1593), Richard Barnfield’s Affectionate Shepherd and Certaine Sonnets (1594–95), Shake-speare’s Sonnets (1590–1604?), and John Donne’s remarkable dramatic monologue in a lesbian voice, Sapho to Philaenis (1613?), homoeroticism in the English Renaissance tends to be expressed implicitly rather than explicitly (Summers 1). Could this have something to do with the fact that works by Shakespeare have such an uneven publishing history, with roughly half remaining unpublished until the First Folio in 1623? Could this have something to do with the likelihood that the name itself, “Shake-speare,” is a semi-obvious cover for a writer whose identity had to be hidden due to his obvious predilection for homoerotic themes and banter?

“There has been a flurry of interest in the whole subject of the homoerotic in Shakespeare …. None of these books attempt to prove that Shakespeare was a practicing homosexual, but by calling attention to the large amount of homoerotic material, they raise serious questions about the nature of love in his works” (Charney 3). “There are obvious homoerotic discourses in Shakespeare’s works that are an important aspect of the theme of love. In Marlowe the homoerotic references are so direct and so overt that critics do not hesitate to speak of Marlowe as a homosexual writer” (159). Also, “Marlowe represents homoerotic situations and incidents in his plays and poems more frequently and more variously than any other major writer of his day” (Summers 22). Although “it is surprising how much same-sex love there is in Shakespeare,” unlike in Marlowe or Barnfield, it is not limited to a particular response, but shows “a dramatic expression of a whole variety of sexual impulses” (Charney 6). As Stanley Wells observes, “From the beginnings of Shakespeare’s career…to the end of it, …his plays are full of close, loving, even passionate male friendships” (9). And, we might add, a few female friendships as well. Unlike our current society, which tends to categorize sexuality as either heterosexual on the one hand or homosexual on the other, many of Shakespeare’s characters would have to be placed somewhere on a continuum between the two, a condition that today we generally term bisexual.

Homosexuality in the Theater

“Much has been written on the public theater as a site of homoerotic titillation and assignation” (DiGangi Family 283). In spite of the anti-sodomy laws, the English theater in the sixteenth century had a strong cross-dressing tradition and was an especially important arena for the expression of various lewd and erotic desires (Thompson 7). “The Elizabethan and Jacobean theater acquired a reputation for homosexuality” (Bray 54). The theater was the target of attacks by Puritans like that of Phillip Stubbes in his Anatomie of Abuses (1583), who derided

the flocking and running to Theaters and Curtains, daily and hourly, night and day, time and tide, to see plays and interludes, where such wanton gestures, such bawdy speeches, such laughing and fleering, such kissing and bussing, such clipping and culling, such winking and glancing of wanton eyes and the like, is used as is wonderful to behold. Then, these goodly pageants being done, every mate sorts to his mate, every one brings another homeward of their way very friendly, and in their secret conclaves covertly they play the sodomites or worse. And these be the fruits of plays and interludes for the most part. (Smith Desire 155)

William Prynne in 1633, “cites this passage as proof of the specifically homoerotic character of the stage” (Orgel 30).

Homoeroticism on the English stage was inescapable, because, for a variety of reasons, plays in England were performed solely by the boy companies or by youths and men in the adult companies. Women did not act on the stage, so the love scenes between Romeo and Juliet, Kate and Petruchio, Antony and Cleopatra, were played, not by a man and a woman, or a youth and a girl, but by two males, adult or juvenile.1

Indeed, seductive boy actors had the reputation of sexually arousing men (Greenblatt 186). These were referred to in sermons and Puritan pamphlets as ganymedes, minions, catamites, or ingles, Elizabethan slang terms for youths used for sexual purposes.2 In Greek mythology, the youth Ganymede was Jove’s cupbearer and minion. In Two Noble Kinsmen, Arcite states, “Just such another wanton Ganymede set Jove afire once” (4.2.15). Ben Jonson, in his Every Man In His Humour, has a page, Cinedo, who seems to be used by his master for sexual purposes. In John Florio’s Italian dictionary of 1598, a cinedo is defined as “a bardarsh, a buggring boy, a wanton boy, an ingle” (DiGangi Drama 70). In Ben Jonson’s play Poetaster, enacted by the Children of the Chapel Royal in 1600, upon hearing that his son wants to become an actor the elder “Ovid” roars, “What? Shall I have my son a stager now, an ingle for players?” (1.2.13–14). “The gallants who frequented the play led fast lives, and were constantly charged with the corruption of innocence” (Bellinger 213).

In 1598, playwright John Marston railed against “male stews” (brothels) and homosexual prostitution in London: “But ho! What Ganymede is this that doth grace the gallant’s heels? One who for two day’s space is closely hired” (33–35). Guilpin and Middleton both satirized urban gallants and their “ganymedes” in 1598 and 1599 (DiGangi Desire 67). Male servants and pages also had the reputation of being used for sexual purposes. Sir Francis Bacon made “his male servants his catamites and bedfellows” (Bray 55). Edward Guilpin also described a sodomite as someone “who is at every play and every night sups with his ingles” (DiGangi Desire 69). This charge is repeated in 1627 by Michael Drayton in his The Moone-Calfe, where the theaters are denounced as one of the haunts of the sodomite (Bray 54–55).

Puritans were particularly offended by boy actors dressed up as women. Did not Deuteronomy 22:5 forbid men to wear women’s clothes? John Rainolds in his Th’Overthrow of Stage-Plays (1599), leaves no doubt about the reason for this prohibition: cross-dressing leads to homosexual acts” (Smith 147). After evaluating the sexual themes and context of the theaters, present-day writer Stephen Orgel concludes that Rainolds had a valid point (7–29).

According to Andrew Gurr, the reopening of the boy’s playing companies in 1599 and 1600 coincided with the expansion of satiric discourse, much of it homoerotic, in print and onstage (153–59). “Before London’s public theaters were closed by Puritan edict in 1642, “play-boys” disguised as girls disguised as boys appeared in at least seventy-five plays by nearly forty playwrights.…Scripts by Fletcher, Massinger, Middleton, Heywood and others, represent, according to Michael Shapiro, exploitation of ideas originally put on the stage by Shakespeare” (Smith Desire 150).

It is interesting to note that specific locales where “gays” would meet did not start developing until after the theaters were closed under Cromwell. According to Alan Bray, it was not until the Restoration in 1660 that “Molly Houses” began to take an identifiable form, at which point the theaters ceased to be a focal meeting place for homosexual encounters (108–14). It was also at this time that women were finally allowed to act at the theaters. With boys no longer required to play women’s roles, this particular form of homoerotic titillation came to an end. However, once women were allowed on the stage, they, like the boys before them, were scorned in the popular mind as little more than whores.

Bisexuality in Shakespeare’s Plays

As You Like It

In Shakespeare’s plays the boy actors sometimes teased the audience about their gender. In As You Like It, for example, the character Rosalind (played by a boy) “disguised” herself as a boy called Ganymede, who was wooed by the shepherdess Phebe (also played by a boy) who was “herself” deeply attached to her cousin Celia (also played by a boy). Lesbian eroticism is suggested when Phebe loves “at first sight” the cross-dressed Rosalind/Ganymede (3.2.398). As Ganymede, Rosalind is free to carry on a “pretend” flirtation with Orlando that would have been unseemly for a female. Orlando’s playful wooing of “Ganymede” as a female, invoked a more complex kind of homoerotic tension for a sixteenth-century audience. Watching Orlando practice his seduction techniques on a boy pretending to be a girl pretending to be a boy pretending to be a girl, the gender confusion goes well beyond the simple amusement it brings today’s audiences, for whom Rosalind is always a female to begin with. Thus Shakespeare cleverly took advantage of the all-male configuration of his company to give additional meaning to the phrase, double entendre. And despite the traditional finale, wherein all issues of class and gender must be resolved in favor of social norms, this play actually ends on a note of gender confusion. When the youth who has played Rosalind/Ganymede delivers the Epilogue, offering to kiss the men in the audience, how can we be sure exactly which character is speaking: Rosalind, Ganymede, or the actor as himself?

If I were a woman I would kiss as many of you as had

beards that pleased me, complexions that liked me, and

breaths that I defied not. And I am sure, as many as

have good beards, or good faces, or sweet breaths will,

for my kind offer, when I make curtsy, bid me farewell. (Ep. 16–21).

Since antiquity, and especially in the Renaissance, Ganymede was a familiar representation both in art and literature of the beautiful Trojan youth, abducted and loved by Jupiter over Juno’s jealous objections. Its most famous English version is to be found in Book X of Arthur Golding’s 1565 translation of Ovid’s Metamorphoses. Ganymede’s story is touched on in both As You Like It and Twelfth Night. That Shakespeare has Rosalind choose Ganymede for her disguise may suggest that she suspects that the way to Orlando’s heart is through his youthful preference for males. “Orlando and Ganymede are therefore legible as a sexually-involved gallant and page — a familiar couple in ‘the street, the ordinary, and stage’ of late sixteenth-century London, if we are to believe the satires contemporary with As You Like It” (DiGangi Family 279). Above all, since As You Like It is clearly a holiday play, it is on the most obvious level a reflection of the holiday pastime known as mumming and disguising, in which cross-dressing for both men and women was a constant, and in which, for that reason, an Elizabethan audience would see no particular significance. One thing we can be certain of where Shakespeare is concerned, any ambiguities and confusions are purposeful and intended to reinforce his message. Nor are they limited to a single interpretation, something we might already have gathered from the title — As You Like It. The subtitle of that other gender-bender, Twelfth Night, or What You Will, sends the same message.

As You Like It was partially based on the bawdy comedy Il Marescalco, an Italian play by Pietro Aretino, which was supposedly based on an actual event at the Gonzaga court of Federigo, Duke of Mantua (Hamill 16). This is one of the earliest plays in which, as a joke, a boy actor is disguised as a girl, tricking the male character into marrying him/her. Shakespeare made use of the same trope in the last act of The Merry Wives of Windsor where both Dr. Caius and Slender are tricked into marrying boys. He used it again in the Induction to The Taming of the Shrew, in which a page is dressed up as a woman to fool a bumpkin into thinking the boy is his wife. In the Induction, the lord requests that the bumpkin be carried “gently to my fairest chamber and hang it round with all my wanton pictures” (Ind. 1.46–47), possibly a reference to I Modi, the famous book of Postures with text by Aretino and pornographic illustrations by Giulio Romano.

Romano was the Renaissance painter/sculptor/architect famous not only for producing the first commercial pornographic book in Europe, but also for his representations of Ganymede in several erotic frescoes in the Palazzo Te at Mantua. No artist in Europe painted more depictions of Ganymede than Giulio Romano (Saslow 84). He was also the only artist mentioned by name by Shakespeare (as the creator of the statue of Hermione in The Winter’s Tale). Shakespeare, whoever he was, was certainly impressed by Giulio Romano.

In Twelfth Night, the confusions about gender are the most complex of all. When the shipwrecked Viola, played by a boy actor, disguises “herself” as Cesario, both Duke Orsino and Lady Olivia are excited by desire. It is surprising to hear Orsino call his beloved Cesario Olivia’s “minion” (5.1.123). Orsino prolongs the confusion to the very end by insisting on calling Viola “Cesario” until he/she/he changes back into female clothes in order to become his wife. “That is, he imagines, not Viola in her female clothes, but a transvestite Cesario. At this moment of comic closure, Cesario is transformed, not into Viola, but Ganymede: the effeminate page, the transvestite boy player, the master-mistress as his ‘master’s mistress’” (5.1.324)(DiGangi Drama 42).

Shakespeare’s transvestite comedies: Twelfth Night, Merry Wives, and As You Like It, encourage the audience to delight in, not just mistaken identities, but in mistaken sexual identities. As Valerie Traub has emphasized, homoeroticism in Shakespeare’s comedies, whether male or female, “is constructed … as merely one more mode of desire” (12), but this is not true of the comedies alone. Two of his dramas also rely on female-to-male cross-dressing as a means of creating tension and dramatic excitement: Portia in Merchant of Venice and Imogen in Cymbeline.

Troilus and Cressida

More openly sexual than the light-hearted gender-bending of the comedies is the relationship between Achilles and Patroclus in Troilus and Cressida. Achilles’s refusal to fight causes Patroclus to be concerned, not just over their reputation, but also that their involvement might in some way have actually weakened Achilles:

To this effect, Achilles, have I moved you:

A woman impudent and mannish grown

Is not more loathèd than an effeminate man

In time of action. I stand condemn’d for this.

They think my little stomach to the war

And your great love to me restrains you thus.

Sweet, rouse yourself, and the weak wanton Cupid

Shall from your neck unloose his amorous fold,

And, like a dew-drop from the lion’s mane, Be shook to air. (3.3.205–215)

Later the forthright Thersites expresses his disdain of Patroclus:

THERSITES: Prithee, be silent, boy; I profit not by thy talk:

thou art thought to be Achilles’ male varlet.

PATROCLUS: Male varlet, you rogue! What’s that?

THERSITES: Why, his masculine whore. (5.1.15–18)

The depiction of Achilles and Patroclus as lovers helps explain the vehemence of Achilles’s revenge when Patroclus is killed by Hector. When he gets the news, Achilles cries: “Where is this Hector? Come, come, thou boy-queller, show thy face! Know what it is to meet Achilles angry!” (5.5.45–48). While Achilles is portrayed as bisexual, Patroclus is the only “outright homosexual” in Shakespeare’s plays (Asimov 473).

Richard II

In Richard II Shakespeare portrays homoerotic love in a much more negative way, one that leads to the overthrow of a king. In the play the Duke of York accuses Richard of succumbing to flattery and delighting in lascivious meters and vile fashions “thrust forth” by Italian imitators (DiGangi Drama 116–17). Then Gaunt brings out what York had only intimated regarding Richard’s sexual will:

A thousand flatterers sit within thy crown,

Whose compass is no bigger than thy head;

And yet, incagèd in so small a verge,

The waste is no whit lesser than thy land. (2.1.197–203)

In Bolingbroke’s denunciations of Bushy and Greene, the site of the transgressions against the King’s body expands from the “small verge” of the crown to the actual bedchamber:

You have misled a prince, a royal king,

A happy gentleman in blood and lineaments,

By you unhappied and disfigured clean:

You have in manner with your sinful hours

Made a divorce betwixt his queen and him,

Broke the possession of a royal bed

And stain’d the beauty of a fair queen’s cheeks

With tears drawn from her eyes by your foul wrongs. (3.1.8–15)

Bolingbroke implies that the male favorites have prevented the royal couple from harmoniously occupying their bed and producing an heir to the throne, while raising the specter of sodomy. Richard’s failure to produce an heir dangerously undermines national stability.

Merchant of Venice

The play that most poignantly depicts romantic friendship between males is The Merchant of Venice, where the love shared by Antonio and Bassanio coexists with Bassanio’s desire to marry. The dilemma of an older man in love with a younger one who is at the same time attracted to a woman is also explored in Twelfth Night, and in the Sonnets.

Both the Antonios of Merchant of Venice and Twelfth Night portray a strong homosexual bond in the face of the impending marriage of their beloved to a woman. Each Antonio loves his friend “more than life itself,” and both are willing to prove it, physically and financially. Unlike characters that are torn between their love for a man and a woman, neither Antonio shows any interest in a woman. The Antonio of The Merchant of Venice assures Bassanio that along with his purse and his “extremest means,” “his person” lies unlocked to his friend’s “occasions” (1.1.138–39). The melancholy that plagues Antonio at the beginning of the play is understood when Bassanio leaves for Belmont to marry Portia. As his friend Salarino comments, “Why then you are in love ….”

I saw Bassanio and Antonio part:

And even there, his eye being big with tears,

Turning his face, he put his hand behind him,

And with affection wondrous sensible

He wrung Bassanio’s hand; and so they parted. (2.8.46–50)

Salanio, adds, “I think he only loves the world for him.” Bassanio in turn is clear about his devotion to Antonio: “to you Antonio, I owe the most in money and in love” (1.1.130–31).

Believing he is about to die, Antonio bids Bassanio farewell and asks him to —

Commend me to your honourable wife:

Tell her the process of Antonio’s end;

Say how I loved you, speak me fair in death;

And, when the tale is told, bid her be judge

Whether Bassanio had not once a love. (4.1.269–73)

— a speech that allows a talented actor to seethe with passion. The “usage of one man as the ‘love’ of another is rare, and with the exception of the Sonnets does not occur elsewhere in Shakespeare, or in the period” (Pequigney ELR 211). “It is understandable, then, that the relationship between Antonio and Bassanio is … most frequently treated in performance as homoerotic.” (Wells 81)

Bassanio, the object of Antonio’s obsession, for whom he has risked all, his money and his life, tells his friend in front of the Venetian court, in front of Shylock and, unknowingly, in front of his own wife Portia, who is present disguised as a male jurist:

Antonio, I am married to a wife

Which is as dear to me as life itself,

But life itself, my wife, and all the world

Are not with me esteemed above thy life.

I would lose all, ay, sacrifice them all

Here to this devil, to deliver you. (4.1.279–84)

At the end, Portia returns the contentious marriage ring to Bassanio through Antonio, saying to him: “Give him this. And bid him keep it better than the other” (5.1.254–55). By this gesture, by returning the ring through the friend, Portia signifies her acceptance of Antonio into the marriage/family. The sexual relationship between the two men is now over (perhaps), but thanks to the trusting magnanimity of Portia, their love at least may continue. That this interpretation of the play’s psychology is now more openly accepted is clear from the recent (2004) film. With Joseph Fiennes as Bassanio, Jeremy Irons as Antonio, and Lynn Collins as Portia, the subtleties of Shakespeare’s love triangle are fully explored for the present-day film audience.

Twelfth Night

Shakespeare’s other homosexual Antonio, the ship’s captain who saves Sebastian’s life in Twelfth Night, is passionately attracted to Viola’s twin brother. Far from suffering the inarticulate melancholy of Antonio in The Merchant of Venice, this Antonio’s love is “the strongest and most direct expression of homoerotic feeling in Shakespeare’s plays” (Adelman 88). After their first meeting, Sebastian and Antonio were inseparable “for three months .… No int’rim, not a minute’s vacancy, both day and night did [we] keep company” (5.1.92–94). When Sebastian instructs his friend not to accompany him because of his “many enemies in Illiria,” Antonio states: “But come what may, I do adore thee so, that danger shall seem sport, and I will go” (2.1.47–48). Separation is so unacceptable to Antonio that he ignores Sebastian’s instructions and follows him to Illiria. Later, when Sebastian thanks Antonio for all the efforts he has taken to rescue him, Antonio replies:

I could not stay behind you. My desire,

More sharp than filèd steel, did spur me forth,

And not all love to see you — though so much

As might have drawn one to a longer voyage —

But jealousy might befall your travel … (3.3.4–8)

Antonio will see to it that they “keep company” this night as he goes off to arrange for their dining and sleeping together at the Elephant Inn. There, says Antonio, “shall you have me” (3.3.42). Later in the play, despite his anger from having confused Sebastian with his uncomprehending twin sister, the obsessed Antonio continues to idolize Sebastian, stressing his beauty: “And to this image, which methought did promise most venerable worth, did I devotion” (3.4 371–75). In the last act, Antonio describes his sacrifices:

That most ingrateful boy there by your side,

From the rude sea’s enraged and foamy mouth

Did I redeem; a wreck past hope he was:

His life I gave him and did thereto add

My love, without retention or restraint,

All his in dedication; for his sake

Did I expose myself, pure for his love,

Into the danger of this adverse town .…

“The only real parallel in Shakespeare for such eroticized speech about a fair youth occurs in the Sonnets” (Pequigney ELR 203).

Nor is Sebastian any less responsive; reunited with his friend, he expresses the most ardent feeling: “Antonio! O my dear Antonio, How have the hours rack’d and tortur’d me since I have lost thee!” (5.1.216–18). Despite having just fallen madly in love with Olivia, Sebastian’s emotions continue to revolve around Antonio.

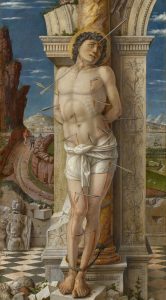

Sebastian’s name is a clue to his bisexuality.3 Considered the (unofficial) patron saint of homosexuals, St. Sebastian was a favorite subject of Renaissance painters, who invariably portrayed his beautiful semi-nude body bound to a column or post and stabbed with a dozen arrows, making it both a homoerotically charged object of desire and a source of solace for the rejected homosexual.

Sebastian and Bassanio, who can erotically respond to both sexes, are clear examples of this recurring theme of bisexuality, while both Antonios, whose desires appear to be limited to males, are two of the few who are purely homosexual. “Bisexual experiences are not the exception but the rule in Twelfth Night, and they are vital to the course of love leading to wedlock for the three principal lovers other than Sebastian: Orsino, Olivia, and Viola” (Pequigney Antonios 207). The author seems to relish this sexual intrigue and the ultimate solution that preserves the open relationship. Though their loves marry, neither Antonio is abandoned or rejected, indeed, as Valentine hopes will happen at the end of Two Gentlemen of Verona, they are incorporated into the “family,” the ultimate “happy ending” for a bisexual.

Latent Homoerotic Desires

Shakespeare’s own homoerotic feelings seem to come through even in situations where no such desires would normally be present, a possible biographical revelation. For instance, in King Lear, the Fool nonchalantly reveals his own sexual bias as he lists what not to trust:

He’s mad that trusts in the tameness of a wolf,

A horse’s health, a boy’s love, or a whore’s oath. (3.6.18–19)

In Henry IV, Part Two, the Hostess, in her sly commentary on Falstaff, says —

In good faith, ’a cares not what mischief he doth,

If his weapon be out he will foin like any devil.

He will spare neither man, woman, nor child. (2.1.15–18)

— a comment that, if taken literally, would make a monster of the old buffoon.

Scenes like the following that express erotic desires in combat and death seem out of place and add nothing to the story. As with Achilles and Patroclus, it is often combat that brings out undertones of eroticism in male friendship (Smith Desire 59). In Henry V, for example, after kissing Suffolk’s wounds, York, a witness reports, turned

… and over Suffolk’s neck

He threw his wounded arm, and kissed his lips,

And so espoused to death, with blood he sealed

A testament of noble-ending love. (4.5.24–27)

We can hear expressions of homoerotic feeling in certain speeches of Shakespeare’s plays, that seem remarkably direct. In Coriolanus for example, the warrior Aufidius welcomes his archenemy in undeniably erotic terms:

… Know thou first,

I loved the maid I married; never man

Sighed truer breath. But that I see thee here,

Thou noble thing, more dances my rapt heart

Than when I first my wedded mistress saw

Bestride my threshold. (4.5.113–18)

According to Stanley Wells, the character who has “surely the most homoerotically charged lines in Shakespeare is Iago, when attempting to substantiate his imputation of Cassio’s adultery with Desdemona, he tells Othello what happened when he shared Cassio’s bed” (84–85):

In sleep I heard him say, “Sweet Desdemona,

Let us be wary, let us hide our loves”;

And then, sir, would he grip and wring my hand,

Cry, “O sweet creature!” then kiss me hard,

As if he pluck’d up kisses by the roots

That grew upon my lips; then laid his leg

Over my thigh, and sigh’d, and kiss’d; and then

Cried, “Cursed fate that gave thee to the Moor!” (3.3.423–30)

“The straightforward description of one man making love to another is anaesthetized by its presentation as a heterosexual dream fantasy .… Besides Cassio, there are at least two other characters in the play to whom Iago might be represented as being sexually attracted — Roderigo and Othello himself” (Wells 85–86). Many actors, among them Sir Laurence Olivier, have chosen to convey the homosexual impulses that drive Iago’s otherwise “motiveless” malignity.

The nonsexual yet intimate bonding in such plays as Henry V, Love’s Labor’s Lost, and A Midsummer Night’s Dream, is also infused with romantic and erotic feeling, as is the more subtle relationship between Falstaff and Prince Hal in Henry IV, Part Two. Again and again, as Smith points out, the plots in Shakespeare’s plays turn on the intimate relationship of two male friends driven apart by a woman: Proteus/Silvia/Valentine, Romeo/Juliet/Mercutio, Bassanio/Portia/Antonio, Sebastian/Olivia/Antonio, Bertram/Helena/Parolles, Othello/Desdemona/Iago, Polixenes/Hermione/Leontes (Desire 66–67) and Palamon/Emilia/Arcite.

For instance, in Romeo and Juliet, the specific object of Mercutio’s sexual and verbal interest is not Juliet’s pudenda, but Romeo’s: “O Romeo, that she were an open arse and thou a popp’rin’pear” (2.1.37–38); “Mercutio’s lewdest verbal jab is an image of anal sex” (Smith Desire 64). Mercutio’s obsession with phallic puns, specifically with puns related to Romeo’s phallus, has also been noted by Joseph Porter and by Donald Foster (286). Similarly, in All’s Well that Ends Well, Sue Sybersma concludes that the role of Parolles runs parallel to Helena’s and Bertram’s throughout the play, while his story is so interwoven with their conflict that it cannot be seen as a mere subplot but as subtly portraying Parolles as a contender for Bertram’s affection (4). Oxfordians see Bertram as a self-portrayal that evokes Oxford’s difficult relationship with his wife, Anne Cecil.

In several cases, in order to maintain their friendship one friend will rather bizarrely offer to give up the woman he loves to the other. This kind of male-to-male bonding had been expressed in English literature before Shakespeare. In Sir Thomas Elyot’s 1531 The Boke of the Governour, friends Titus and Gysippus are inseparable until Gysippus falls in love with Sophronia and wishes to marry her, but when he realizes that Titus is also in love with her, he relinquishes her to his friend. Lyly’s Endimion also shares this plot.

The Governour and Endimion are cited by Bullough as possible sources for Two Gentlemen of Verona. In this play, the bond between two friends is most clearly demonstrated at the end when Valentine graciously offers his beloved Silvia to his friend Proteus, following his attempt to rape her! The happy ending is announced by Valentine: “And, that my love may appear plain and free, all that was mine in Silvia I give to thee” (5.4.82–83). Silvia is to be disposed of as if she were cattle. (It is noteworthy that Silvia has no lines in this scene.) Indeed, Valentine entertains the hope that now that he and his friend Proteus are both betrothed to be married, they will enjoy “One feast, one house, one mutual happiness” (5.4.171). As with Bassanio and Antonio, though Valentine is marrying, he is concerned not to lose the love or the company of Proteus.

Similar feelings of generosity may be expressed in Sonnet 40 concerning a relationship that seems to be developing between the Fair Youth and the Dark Lady.

Take all my loves, my love, yea, take them all;

What hast thou then more than thou hadst before?

No love, my love, that thou mayst true love call;

All mine was thine before thou hadst this more.

In the play Two Noble Kinsmen, “Palamon and Arcite’s discourse is full of homoerotic terms expressing their love and devotion to each other” (Charney 161), as when Arcite says to Palamon:

And here being thus together,

We are an endless mine to one another;

We are one another’s wife, ever begetting

New births of love. (2.1.137–40)

A little later Palamon asks: “Is there any record of any two that loved better than we do, Arcite?” Arcite replies: “Sure there cannot.” Yet these sentiments do not appear to conflict in any way with their interest in the opposite sex.

Essentially, Shakespeare did not portray sexual identity as rigidly polarized, nor did he present homosexual and heterosexual desires as incompatible or mutually exclusive. Shakespeare portrays almost as many different kinds of human sexual response as he has characters, thereby calling into question, whether purposely or not, sexual roles as defined by tradition.

Homoeroticism in the Poetry:

Venus and Adonis

Shakespeare’s long narrative poem shares a homoerotic focus with other examples of the genre like Marlowe’s Hero and Leander (printed 1598) and Francis Beaumont’s Salmacis and Hermaphroditus (1602). These seem to be aimed at a particular audience that found this theme appealing. Dedicated to Henry Wriothesley, Earl of Southampton, this interest shows up not in the plot situation in which the aggressive goddess Venus falls in love with the adolescent Adonis, but in the perspective that the likely mostly male readers are invited to take toward that situation. Erotic desire in the poem is all on Venus’s side. The center of erotic attention is not her body, but that of Adonis. As Bruce Smith notes:

Looking at Adonis through Venus’s eyes, the reader discovers a hermaphroditic charm not unlike that radiated by the cross-dressed heroines of Shakespeare’s comedies or the fair youth of the Sonnets. Wooed by Venus, Adonis blushes like a maiden (l.50). His voice is like a mermaid’s (l.429). His face is hairless (l.487). When, in desperation, Venus wrestles this paragon of beauty to the ground, the reader joins Venus in the active role of ravishing him (Shakespeare 656).

Now quick desire hath caught the yielding prey,

And glutton-like she feeds, yet never filleth.

Her lips are conquerors, his lips obey,

Paying what ransom the insulter willeth,

Whose vulture thought doth pitch the price so high

That she will draw his lips’ rich treasure dry. (547–552)

But alas for Venus, Adonis is not interested; he would rather go hunting with his friends.

The fact that this poem was dedicated to Henry Wriothesley, the young Earl of Southampton, who according to his biographers, seems to match the physical and psychological description of Adonis, is revealing. Were the poet’s sympathies with Adonis, or with Venus? Would Southampton have identified with Adonis? Is Adonis modeled on the same aloof youth of the Sonnets?

Finally, probably from frustration, and seen from the perspective shared by Venus and the reader, the goring of Adonis by a wild boar is portrayed as an act of rape or seduction:

’Tis true, ’tis true; thus was Adonis slain;

He ran upon the boar with his sharp spear,

Who did not whet his teeth at him again,

But by a kiss thought to persuade him there,

And, nuzzling in his flank, the loving swine

Sheathed unaware the tusk in his soft groin. (1111–1116)

States Campbell: “Failure to construe the [homosexual] imagery here is an instance of scholars’ tendency to notice Shakespeare’s bawdy only when it is heterosexual” (136).

The Rape of Lucrece

Also dedicated to Southampton, The Rape of Lucrece, published in 1594, is more sexual even than Venus and Adonis. The poem focuses again on the familiar theme of two male allies set apart by a woman (Smith Shakespeare 6). However, it is not this that has attracted the most attention, but the remarkable tone of the dedication: “The love I dedicate to your lordship is without end …. What I have done is yours; what I have to do is yours; being part in all I have ….”

“Speaking of the overflowing affection in these lines, Nichol Smith declared, ‘There is no other dedication like this in Elizabethan literature’” (Akrigg 198). What he is actually saying is that there is no other dedication with such homoerotic overtones. “This was not, as might have been expected, an exercise in praise … this was a public declaration of fervent, boundless love” (Greenblatt 246). Many others have also noted the similarity in tone and language to the tone used in addressing the Fair Youth in the Sonnets.

Shake-speare’s Sonnets

The Sonnets are the most tantalizing and controversial of Shakespeare’s works. They have been interpreted to prove almost any scenario. For us the interpretation is critical, because if it can be shown that they are autobiographical, it would reveal much about the author’s sexual orientation. “By every indication, Shakespeare had nothing to do with publishing the volume of ‘Shakespeares Sonnets’ that the printer Thomas Thorpe put on the market in 1609” (Smith Shakespeare 7). The best evidence of this is that, unlike the poems, which were very carefully proofread, the Sonnets are full of errors and the dedication was not by the author, but by the publisher.

Because the Sonnets may imply a scandalous autobiography and one that does not match anything we know about Shakspere of Stratford, many scholars have tried to separate the speaker “I” in the sonnets from the author in order to disassociate the author from the seeming homosexual and adulterous passions he describes. In this view, the Sonnets are no more than a literary exercise, and so do not reflect actual events. But since they were published over a decade after the decade-long “sonnet craze” ended in 1597, sonnet cycles of this sort would have been outdated by 1609 (Berryman 263). If Shake-speare’s Sonnets was written for commercial purposes, it missed its market by twelve years. If the Sonnets are not autobiographical, why publish so late? Why not give the characters names? Why be so ambiguous about everything but the emotions?

If the Master Storyteller chose to hide his characters and plot behind a veil of mystery it must have been for a reason. The most likely explanation is that the characters and events are too real to reveal to any readers but those most intimately involved. Understanding how sexual the Sonnets are, the need for anonymity should be clear. This anonymity and subtlety are necessary for the author’s own protection as much as for his loved ones, for if any of the protagonists could be identified, not only embarrassment but potentially dishonor and ruin would befall all involved.

This is the only time that the author uses the first person perspective, the “I,” in his writings. If he ever wrote autobiographically, he did so in the Sonnets, another clue that the name used by the author, “Shakespeare,” must be an alias. Why hide the names of the characters in the Sonnets and reveal his own? Shakspere of Stratford experienced no known repercussions as a result of the publication of the Sonnets. In fact, unlike Marlowe, Bacon, or Oxford, Shakspere of Stratford was never accused of a sexual crime. For the seven years remaining between the publication of the Sonnets and his death in 1616, not a word in any document or publication makes a connection between the two.

By its heading alone, “Shake-speares Sonnets, Never before Imprinted,” the book not only communicates a sense of privacy breached, but that these are all the sonnets that “Shake-speare” ever wrote, or ever will write. The title itself carries a sense of finality, a sense confirmed by the preface in which Thomas Thorpe praises “our ever-living poet,” a term used exclusively for those that have attained immortality (Sobran 94). It should be clear that by the time the Sonnets were published, the author was dead.

“He was but one hour mine”

The Sonnets are different from other sonnet sequences because “like some of Richard Barnfield’s, but none, so far as I know, by any other sonneteer of the period, many of Shakespeare’s sonnets are explicitly addressed to, or concern, a man” (Wells 53). Sonnet cycles were the established format to express one’s most intimate and passionate feelings for an idealized loved one, but in all but these two instances the loved object is a female. The majority of the poems — 126 of 154 — are concerned with the author’s obsession with a fair-complexioned young nobleman of surpassing physical beauty, who, though idealized, is of questionable character and who is considerably younger than the speaker. Looney, while he avoids the subject of homosexuality, admitted that sonnets, traditionally, have been

the vehicle for the expression of the most intimate thought and feelings of poets. Almost infallibly, one might say, do a man’s sonnets directly reveal his soul .… [Shakespeare’s Sonnets] express a tenderness, which is probably without parallel in the recorded expressions of emotional attachment of one man to another. (100)

The first seventeen sonnets are the so-called marriage sonnets, in which the poet urges the Fair Youth to procreate, to make a copy of himself for posterity. According to Bruce R. Smith, by Sonnet 16 (“But wherefore do not you a mightier way / Make war upon the bloody tyrant, time”), the author has begun … to insinuate his own designs on the young man, first by promising to preserve the young man’s beauty in the medium of verse, then by speaking more and more openly about his own desires. The following sonnets — up to #126 — shift in interest to describe a growing obsession with the Fair Youth, continuously praising his beauty and claiming that he will immortalize that beauty in his verse (nothing more is said from then on about marriage and children). By Sonnet 18 (“Shall I compare thee to a summer’s day”?), the Poet himself has fallen in love with the Youth.

The pair formed by Sonnets 20 (“A woman’s face with nature’s own hand painted, hast thou, the master-mistress of my passion”) and 21 (“So is it not with me as with that muse, stirred by a painted beauty to his verse”) conjoin the two things that preoccupy the speaker in all the ensuing sonnets to the young man: making love and making verse (Smith Shakespeare 7). His infatuation continues through 126 sonnets before the sequence ends with the final 28. These last are written to a woman by whom the author is sexually aroused and whom he alternately praises and reviles.

The author of the Sonnets dwells on the emotional and sexual love of a young man and a woman, expressing it through numerous creative puns with such dexterity that much of the sexual imagery can be overlooked by the casual reader. “Stephen Booth’s ingenuity has revealed how charged these poems are — even the most idealistic ones — with sexual puns” (Smith Desire 229). Martin Seymor-Smith states, “It is likely that at least on one occasion Shakespeare did have some kind of physical relationship with the Friend. The sonnets addressed to him, particularly 33–36, are difficult to explain under any other hypothesis.” This seems to be the result of an intimacy, however brief: “he was but one hour mine” (34), a view that, long before Queer Theory, had been expressed by Samuel Butler, Martin Smith, Gore Vidal, and numerous others (Hughes 6).

“None of Shakespeare’s poems are as explicitly homoerotic as any of Barnfield’s. Yet Shake-speare’s are more intense in their expression of love — perhaps simply because Shakespeare was the greater poet” (Wells 65). The homosexual consciousness of the first 126 sonnets is seen not merely in the celebrations of the young man’s beauty, in the obsessiveness of the author’s love, or even in his repeated attempts to define his relationship with the young man in terms of marriage (“So I shall live, supposing thou art true, like a deceived husband”; “Let me not to the marriage of true minds admit impediments”), but also in his profound sense of being different (121–22).

This sense of difference is expressed without apology in the startling and angry Sonnet 121, in which the author declares “I am that I am,” defiantly defending a sexuality that is socially maligned; Giroux interprets it “as Shakespeare’s response to the ‘reproach’ of being homosexual” (30). For Summers (3) and Pequigny (Love 99), the sonnets that reflect alienation, abnegation, and resignation, that give “Shake-speare’s” sequence its distinctive aura of embattlement, despair, and melancholy, correspond particularly well to a homosexual theme, one of forbidden and frustrated love. In the context of the first 126 sonnets there is no doubt as to what type of sexuality this is: his love for the Fair Youth, the object of all these sonnets. He challenges contemporaries who criticize his amorous conduct, which to his mind is defensible, though reproached by others. Stating that, despite how others view it, his sexual “pleasure” is made just rather than vile “by our feeling,” he moves from a defensive stance to counterattack when he reproaches his reproachers for their own “rank” thoughts:

’Tis better to be vile than vile esteemed,

When not to be receives reproach of being;

And the just pleasure lost, which is so deemed

Not by our feeling, but by others’ seeing:

For why should others’ false adulterate eyes

Give salutation to my sportive blood?

Or on my frailties, why are frailer spies,

Which in their wills count bad what I think good?

No, I am that I am, and they that level

At my abuses reckon up their own:

I may be straight though they themselves be bevel;

By their rank thoughts, my deeds must not be shown;

Unless this general evil they maintain,

All men are bad and in their badness reign.

Robert Giroux asserts, “My own conclusion, based on the poet’s gradual self-discovery revealed by the first twenty sonnets, and on Sonnets 104, 108, 121, and 144 in particular, is that Shakespeare experienced real love” (Giroux 25). Greenblatt agrees: Shakespeare “became aware that he was longing for the youth himself .… He is in love with him (339). Joseph Pequigney, who has had significant influence in academia on the interpretation of the Sonnets, writes:

I argue: (1) that the friendship treated in Sonnets 1–126 is decidedly amorous-passionate to a degree and in ways not dreamed of in the published philology, the interaction between the friends being sexual in both orientation and practice; (2) that verbal data are clear and copious in detailing physical intimacies between them; (3) that the psychological dynamics of the poet’s relations with the friend comply in large measure with those expounded in Freud’s authoritative discussions of homosexuality.4 (Love 1)

Many of the poems are immersed in expressions of obsessive desire and of grief in his absence. The author speaks of emotions that typically affect the lovesick: of sleepless nights when the poet’s thoughts make a pilgrimage to the beloved (27 and 61), of the poet as a slave to his friend’s desire (57), of being deceived (93), of sexual dependency (75). Paul Ramsey concedes that the clause “Thy self thou gav’st” at 87.9, if said of a woman, would certainly suggest consummation.” Why should the identical clause take another meaning if the recipient is a man? (Pequigney Love 50). Several times the young man is cryptically referred to as the speaker’s “Rose” — traditionally used in poetry as a symbol of great passion (1.2, 54.11–13, 67.8, 95.2–3, 98.10–11, 109.13–14)” (Smith Desire 252). “Rose” could also be a pun on the likely dedicatee of the Sonnets, Henry Wriothesley, whose name was probably pronounced Rosely (Green 15–37). And because it is unlikely that the author would address more than one as his “Rose,” it should also be clear that he is always addressing the same youth.

In addition, Pequigny recounts how the Sonnets are filled with recurrent expressions of anxious sexual jealousy (Love 102–03). In Sonnets 33–35, the author reacts bitterly to the fact that the youth has had sexual relations with someone else, but when he begs for forgiveness, he is forgiven. Sonnets 40–42 refer to a sexual triangle between the Poet, the Youth and a woman. In Sonnets 48, 49, 57, 58, 61, and 69 the author expresses anxiety over the youth’s faithfulness. In Sonnets 78–86 the author relates his bitterness at the youth’s attraction to a rival male poet. In Sonnets 87–96 the author is haunted again by fears of the youth’s waning love and concern over potential scandal (in fact the couplet of 96 exactly repeats the couplet in 36, which expresses the need for caution about exposing their relationship to the public). In Sonnets 106–112 which seem to take place after a lull in time, and again in 117–120, the author again admits transgressions and begs forgiveness. In Sonnets 133–144, addressed to the Dark Lady, the author refers to the same sexual triangle as described in Sonnets 40–42, in which he blames her, not the Youth, for their deceit.

“The love which he (the author) felt for Southampton may well have been the most intense emotion of his life” (Akrigg 237). Stanley Wells concludes: “It would be a naive young man who, addressed in these terms, did not regard himself as the object of desire. If Shakespeare himself did not, in the fullest sense of the word, love a man, he certainly understood the feelings of those who do” (Wells 65). Though they may imply it, these two scholars cannot bring themselves to state the obvious: that Shakespeare was bisexual. Bruce R. Smith suggests that “the difficulty that modern readers have had with the sexuality of Shake-speare’s Sonnets has been less a problem with decoding these sexual puns than with assuming that the speaker cannot be erotically involved with a man and a woman at the same time” (Smith Shakespeare 8).

While the sexuality of the sonnets addressed to the Dark Lady is quite explicit and is not questioned, “the notion that such a relationship is implicit in the earlier group was for a long time anathema to admirers of Shakespeare” (Wells 60). The author is obsessed and conflicted by his attraction to both of his subjects, as Sonnet 144 confesses:

Two loves have I, of comfort and despair,

Which like two spirits do suggest me still.

The better angel is a man right fair,

The worser spirit a woman colored ill.

Yet, there is still controversy on whether he wants both of them sexually. Taken altogether, the sonnets to the Fair Youth seems to tell the story of a growing obsessive love, one that’s consummated, if only briefly or infrequently, while the relationship with the woman, while altogether sexual, is frequently despised. The idealized relationship with the youth may best be seen as a failed love affair, one in which a woman, as in many of the plays, interferes with their relationship. And again, as in the plays, both of these men appear to be bisexual.

The Heterosexualization of the Sonnets

That thirty-one years elapsed without a second edition of Shake-speare’s Sonnets indicates either that further publication was forbidden by the authorities or that publishers feared to promote it. (Venus and Adonis had gone through no fewer than sixteen editions by 1640.) Their (possible) early suppression may have been caused by the high rank and political importance of the Fair Youth, who was fully grown by 1609, but their subsequent neglect is surely attributable to their portrayal of homosexual desire.

This seems confirmed by the extraordinary lengths the publisher of the second (1640) edition, John Benson, went to disguise the homoeroticism of the original. Surely it was to conceal the fact that the first 126 sonnets were written to a male that Benson rearranged them, changed a few “he’s” to “she’s,” adding spurious titles to suggest that the poet’s interest was solely directed to a female, and, in the process, obliterating the Fair Youth and any hint of a real story (de Grazia 146). Then, as Bruce R. Smith points out, “when George Granville adapted The Merchant of Venice for a production in 1701, he supplied a prologue in which the ghost of Shakespeare, conversing with the ghost of the Restoration playwright John Dryden, makes a point of disowning any suspicion of homosexuality.” “Dryden” begins by berating current audiences who prefer “French Grimace, Buffoons, and Mimics” to British drama:

Through perspectives revers’d they Nature’s view,

Which gives the passions images, not true.

Strephon for Strephon sighs; and Sapho dies,

Shot to the soul by brighter Sapho’s eyes…

“Shakespeare” is horrified:

These crimes unknown, in our less polish’d age,

Now seem above correction of the Stage … (Shakespeare 9)

“The message here is clear: Shakespeare is not a sodomite! In the newly-refined culture of the eighteenth century, “the homoeroticism in Shakespeare’s works became unreadable and unspeakable” (658). Even to consider that the greatest sonnets in the English language may have been inspired by homoerotic passion had become unthinkable.

It was not until 1780, when Edmund Malone and George Steevens published their edition of Shakespeare’s works, restoring the original pronouns, format and order of the sonnets, that the current understanding slowly began to take root, namely that the first 126 sonnets were addressed to a male (Pequigney Love 2–3). After nearly a century-and-a-half of believing that all of them were erotic love poems addressed to a woman, many were understandably shocked to learn that most of the Sonnets were addressed to a teenaged boy.

In reaction to Sonnet 20 (“A woman’s face with nature’s own hand painted hast thou, the master-mistress of my passion”), Steevens felt compelled to exclaim: “It is impossible to read this fulsome panegyrick, addressed to a male object, without an equal mixture of disgust and indignation” (de Grazia 148). To make clear what he was talking about, Steevens cited the term “male varlet” from Troilus and Cressida (Smith History 16). It is clear that, rather than reading this sonnet as a denial of sexual interest in the youth, Steevens saw it as a confirmation that the poet was in love.

Suddenly there was some explaining to be done. Edmund Malone, Steeven’s co-editor and arguably the first great Shakespeare scholar, saved the day by explaining that “such addresses to men, however indelicate, were customary in our author’s time, and neither imported criminality nor were esteemed indecorous” (Sobran 98). Keevak points to attempts by scholars such as Malone, Coleridge, and Boswell to circumvent an unnamed danger (that the Bard could have been guilty of sodomy) by asserting that any suggestion of sexual attraction between males (in the poems or plays) represents “not a love affair between men but only an idealized friendship,” one that is not really sexual (39).

But Pequigny denies that this was ever a customary way for heterosexual men to address each other, either then or now (Love 19): “The language of Sonnet 20 through 126 is, as C.S. Lewis justly observes, ‘too lover-like for that of ordinary male friendship,’ continuing, ‘I have found no real parallel to such language between friends in sixteenth-century literature’ (503). Such a statement from one who spent his entire career from matriculation to the grave, studying, teaching and writing about early modern English literature, first at Magdalen College, then as the first Professor of Medieval and Renaissance Literature at Cambridge University, should, one would think, command the utmost respect.”

Pequigney further notes (76) that the author “keeps referring to the beloved as his ‘love’ (13.1, 22.9, 89.5), ‘my love’ (40.1, 3), ‘dear my love’ (13.13), or ‘sweet love’ (76.9), and for this form of address between men I can find no precedent whatever. This term of endearment was never employed by friends in the Renaissance, though it was by lovers to their ladies. The vocatives supply fresh and substantial evidence of eroticism in the conversation between the poet and his young ‘love’.”

Throughout the first seventeen sonnets, Pequigney notes (19): “In praising his beauty while continually adverting to its procreational use, masturbatorial misuse, (Sonnet 4 — ‘having traffic with thyself alone’), and celibate nonuse, the praiser manifests a mental habit of yoking that youthful masculinity with sex. This repeated reaction, in poem after poem, to another male is problematical. It is not to be accounted for as Renaissance friendship and commentators who hold that it is never produce the requisite precedents.”

An even more belabored attempt to avoid the suggestion of homoerotic desire was Malone’s rationalization of Shakespeare’s references to himself as the “lover” of the male youth. Malone’s longest footnote, stretching across six pages, pertains to Sonnet 93 (“So shall I live supposing thou art true”) which dwells on sexual jealousy. Malone would avoid the scandal that Shakespeare experienced sexual jealousy for a youth by changing Shakespeare’s youth to Shakespeare’s wife, thereby violating his own ascription of the first 126 sonnets to a male!

Some such as James Boswell sought to avoid the issue by claiming that the sonnets were not sexual because they were simply a literary exercise written in imitation of classical Roman homoerotic poetry (de Grazia 152). But why would a heterosexual writer choose to imitate poetry concerning homosexual love when the literature is replete with heterosexual models, especially in an age when homosexual love could not only lead to social disgrace, but terrible legal consequences?

The history of Sonnets criticism in the nineteenth and twentieth centuries has been a history of tortured logic as one desperate attempt after another attempted to prove that Malone was right, among them Michael Wood in his book Shakespeare, where he suggests that Shakespeare was addressing his eleven-year-old son Hamnet in the Sonnets (166)!5 Even so, by 1991 Bruce R. Smith could make the claim that, “Since Joseph Pequigney’s Such Is My Love, Malone’s argument has finally begun to be questioned, however reluctantly” (231), while in her 1997 book on the Sonnets, Helen Vendler (15) was forced to agree that, since Pequigney, there has been an increasing willingness to admit that the controlling motive of the first 126 sonnets was sexual infatuation with a youth.

Yet, despite the growing acceptance of the true nature of the Sonnets, their homoeroticism still continues to cause trouble. Edward Dowden, who wrote as long ago as 1881, may best express the main reason so many would prefer them to be fictional — homophobia — fear of homosexuality: “The moment … we regard the Sonnets as autobiographical, we find ourselves in the presence of doubts and difficulties, exaggerated, it is true, by many writers, yet certainly real” (Smith History 18). As the poet Robert Browning put it: “Did Shakespeare unlock his heart? Then so much less the Shakespeare he.”

Reluctance to acknowledge homoeroticism in works by Shakespeare, the pillar of British literature, appears even in the statements of English poets and writers known to be homosexuals themselves. The great English poet, W.H. Auden, himself openly gay, confessed to a gathering at Igor Stravinsky’s apartment in the early 1960s that “it won’t do just yet to admit that the top Bard was in ‘the homintern’” (Smith Desire 231).6 In his preface to the New American Library paperback of the Sonnets the same year, Auden reinforced this stance. Homosexual readers, he complains in this preface, “have ignored the fact that the sonnets to ‘the dark lady’ are unequivocally sexual and that Shakespeare, after all, was a married man and a father” (qtd. in Pequigney Love 79)

A.L. Rowse, poet, historian, Shakespeare scholar, and a confessed homosexual, insists that Shakespeare was not only not homosexual, he was overly heterosexual. According to Rowse, the purpose of the Sonnets was purely to urge his patron, Southampton, to marry, and so were written in terms that might persuade the as-yet sexually ambiguous and narcissistic youth. “There is not the slightest trace of homosexuality in Shakespeare or even interest in the subject — as there was in Marlowe and Bacon,” says Rowse (Shakespeare 144).

Despite these and other similar denials, the evidence of homoeroticism in the plays, narrative poems, and autobiographical sonnets clearly points to an author who experienced sexual desires for men as well as women. And that the theme of a love/sex triangle consisting of two males and a female repeats so often in the works of Shakespeare strongly suggests that this was a theme that ran through the author’s own life, one that we would expect to find traces of in his biography.

The Sexuality of the Author

As to the sexuality of William Shakspere of Stratford, we have next to nothing with which to make a determination. We have no personal letters from him or to him and no one else makes any reference to his personal life. There is no oral tradition of any kind in Stratford for Shakspere. In the end, Shakspere dictated a standard will which states nothing about his love for his wife or daughters or indeed anyone else. His heartiest commendations are for the local loan shark.

The Earl of Oxford, on the other hand, fits all eighteen of J.T. Looney’s characteristics of Shakespeare, including the rather vague second to the last (103): “Doubtful and somewhat conflicting in his attitude to woman.” To this we can add the 1998 observations of psychologist Harold Grier McCurdy, who concluded, after evaluating the Shakespeare canon, that the he saw the playwright as “a bisexual personality, predominantly masculine, aggressive, prone to wide fluctuations of mood” (549). Thus, solid evidence that Oxford was bisexual should certainly add to his status as leading candidate for the authorship of the Shakespeare canon.

Yet such evidence is understandably rare for anyone from that period. There is little argument about the homosexuality of several writers from the period, such as Marlowe, the Bacon brothers, and Oxford’s cousin, Henry Howard, later Earl of Northampton. Sir John Harrington, the Queen’s cousin, is another possibility. Author of a considerable body of poetry, though little of it about love, Harington never married, a thing that means nothing today but that was highly unusual at a time when, for dynastic reasons, homosexual aristocrats married and had children. The best known example of this is King James, who despite his male favorites, secured the Stuart dynasty by marrying and having children. It is thought that Richard Barnfield, author of the only published homoerotic sonnets other than Shakespeare’s, later married and had children (entry in Encyclopedia Britannia, 1911). John Donne’s passionate love poetry, some written for men (41, 45), some for women, is solid evidence of his either/or bias. Donne married and fathered twelve children.

Evidence for Oxford’s bias would most likely be found in four areas: his relationship with his wife and other women, the charges launched at him by his cousin Henry Howard and Gabriel Harvey, his involvement in the theater, and his connection, if any, with the Earl of Southampton.

As for the first, it is clear that Oxford had sexual relations with women. He married twice, fathering five legitimate children. More to the point, he had at least two mistresses, one of whom gave him a son. It seems evident that his relationship with this last, Anne Vavasour, a Queen’s Maid of Honor, was a genuine passion, as he was reported to be making plans at one point to elope with her to Spain (Nelson 231–32). Nevertheless, the fact that his relationship with his wife was fraught with tension and that it resulted in his breaking off with her entirely, opens the door to another interpretation than that he suspected her of adultery or that he wished to be free from the interference of her father, Lord Burghley. It may also have been a simple preference for the lifestyle of a bachelor, one he managed to maintain in the company of male secretaries and pages for at least nine years until forced back into the family fold by order of the Queen.

The showdown with his cousin Henry Howard and former friend Charles Arundel in 1581–84, in which both sides accused each other of treason, has left Oxford accused by historians of having “buggered” several youthful members of his household. To put this into context, Howard also accused him of having sex with sheep, mares, and ghosts, and with making such statements as, “when women were unsweet, fine young boys were in season” (Nelson 213–18).

Naturally, it must be considered that Howard and Arundel hoped to do as much damage as possible to Oxford’s credibility with the Queen, which then was at its peak, and to save themselves from the Tower or worse. Despite the frequent truth of the old saying: where there’s smoke there’s fire, sometimes all there is is smoke and more testimony is required than the ravings of frightened enemies.

Orazio Cuoco, a sixteen-year-old youth of Venice whom Oxford had taken into his household during his stay in 1575, and who had accompanied him to England in 1576, remained in his London household for about a year as his page, during the period that Oxford was separated from his wife. Upon the youth’s return to Venice in 1577, when questioned by the Inquisition about his patron’s religious practices, Orazio had nothing negative to say on this or any other subject (Nelson 155–57). It should be noted that simply keeping a page, a long tradition with the nobility, was hardly an indication of sexual impropriety; no doubt some were abused, but the expectation was always that they would be treated with respect.

Still, in view of Oxford’s known reputation for wild behavior, it may be that Howard and Arundel were aware that their allegations would be credible. Indeed, we do have a picture of Oxford that could support their accusations. Over a period of years, Gabriel Harvey, the Cambridge don, made consistently disparaging remarks about Oxford. In June 1580, just prior to the Howard and Arundel libels, Harvey, in his Speculum Tuscanismi, described him as “vain,” “frivolous,” “womanish,” “no man, but minion” (Nelson 225–27). Harvey was forced to apologize, but then in 1589, he again attacked Oxford with not very subtle puns, accusing his amanuensis, John Lyly, of being his “minion secretary,” and “once the foil [mirror] of Oxford, now the stale [prostitute] of London.”7

The claim has been made that the homosexual allegations of Howard and Arundel must be false since the Queen obviously didn’t believe them, as she did nothing about them. Yet, while it is true that charges of pederasty were considered serious, they were rarely prosecuted against anyone and never against anyone of Oxford’s rank. Francis Bacon and his brother Anthony, both known homosexuals, present a parallel case involving some of the same principals. Anthony was tried and convicted of sodomy in Navarre in 1586–87. In France at that time, unlike England, sodomy was treated seriously as a capital crime, punishable by burning at the stake. However, it was Anthony’s luck to be good friends with the King of Navarre (later Henri IV of France), who personally intervened and had the sentence quashed (Jardine 107–10). Although at the time “all traces of this awkward affair were carefully eliminated from English records,” the facts were uncovered 400 years later in the French archives by Daphne du Maurier, a descendant of the Bacon family (60–67). This scandalous and embarrassing event was apparently never mentioned by anyone in their private correspondence (or if it was, it has not survived), either in England or in France. If Anthony Bacon’s international sex scandal could be suppressed so effectively, certainly the fact that an eccentric lord was accused of sodomy (or of scripting plays under an alias) could also be suppressed.

For whatever reason, and for all their brilliance, both Bacon brothers were seemingly disapproved of by the Queen, as were Oxford and Southampton. Despite their various talents and training, none of them were given positions of office and power on a level with their qualifications until after her death. Could it have been their perceived homosexuality? (Could it be that her peculiar rage over Southampton’s relationship with Essex had a similar cause?) It is also interesting to note that as soon as she died, both Oxford and Southampton were given significant gifts and offices, while Francis Bacon rose rapidly in Court office, ultimately to become Lord Chancellor, all due to the friendly offices of the homosexual King James.

Although Oxford’s recorded involvement in the theater from 1583 to 1604 does not give automatic evidence of homosexual behavior, it does put him squarely in the environment that, as shown above, was giving most concern to the city fathers due to the erotic content of the plays, the initiation of the boy actors into cross-dressing and erotic role-playing, and the theaters as places where sexual assignations of all kinds could easily take place. During the period of the early 1580s when he was patron of the combined boy companies of the Children of Paul’s and the Children of the Chapel, Oxford was in a position of power with regard to these boys, whose ages ranged from eight to fourteen (or whenever their voices deepened). It also seems likely that the Master of the Children’s Chapel from 1550 to 1583, Sebastian Westcott, was a homosexual. He never married and his closest relationships were with certain of his charges, to whom he left his estate when he died (Chambers 2.15–16). If Oxford was Shakespeare, and was writing for the boys while he was their patron, he was surely providing some of the very material that the puritans were finding so offensive. This proves nothing about his actual behavior, but it shows that he had the opportunity.

Finally, the question of whether or not Oxford had a relationship with Henry Wriothesley, Third Earl of Southampton, is important because Southampton has been confirmed as the Fair Youth of the Sonnets, the work by Shakespeare that is most certainly autobiographical in nature.

Shakespeare, Oxford, and the Earl of Southampton

Most orthodox scholars agree that Southampton was the Fair Youth of the Sonnets. There are several compelling reasons for this. Southampton was the only person to whom Shakespeare dedicated any of his works, the two long narrative poems, Venus and Adonis and The Rape of Lucrece. The similarity of the tone and language of Sonnet 26 (“Lord of my love, to whom in vassalage thy merit hath my duty strongly knit, to thee I send this written embassage, to witness duty, not to show my wit … Then may I dare to boast how I do love thee”), to the tone and language of the dedication in Lucrece (“The love I dedicate to your lordship is without end … What I have done is yours; what I have to do is yours; being part in all I have …”), has been noted by many scholars (Hughes 7). This dedication reinforces the public acknowledgment of the sentiment expressed in Sonnet 26 — “This I do vow, and this shall ever be; I will be true, despite [Time’s] scythe and thee.” According to scholars who have studied and commented on them over the past fifty years or so, the early sonnets were written at the same time as Venus and Adonis and Lucrece, the early 1590s.8

Southampton, born in 1573, turned seventeen in 1590, an appropriate age for the Fair Youth. He was considered “fair” as is the “lovely boy” of the Sonnets. He was a nobleman, as they imply. The Sonnets inform us that the youth’s father was dead (“you had a Father, let your Son say so”) (13, 14), while his mother was living (3) as were Southampton’s parents. Most significant is the fact that, at this same time, Southampton’s guardian, Lord Burghley, was pressuring him to marry, a theme reflected in the first seventeen sonnets, the so-called “Marriage Sonnets.” Although there is no document directly connecting Oxford and Southampton, the fact that it was Oxford’s daughter that Southampton was being urged to marry at the same time that the Marriage Sonnets were being written demonstrates a connection that requires little else to confirm their relationship. Oxford’s age fits as well, since Sonnet 2 — “When forty winters shall besiege thy brow” — could refer to the fact that Oxford turned forty in 1590.9

This first series of sonnets do not identify the potential bride, nor do they state that it is the poet’s daughter that the youth should marry — to be more specific would have prevented them from ever being shared or published. And, since Southampton was still a self-absorbed seventeen-year-old with no interest as yet in marriage or women, it makes sense that a prospective father-in-law might portray the dynastic need to marry and beget children in narcissistic terms of preserving the youth’s own beauty and virtue. The following year, the first book to be dedicated to Southampton, Narcissus, was written by John Clapham, Lord Burghley’s secretary — its theme the dangers of self-love. The sonnets seem to flow chronologically from about 1590 until Sonnet 105. Sonnet 106 seems to represent a jump in several years. Rendall believes that they jump to March 1603 with the release of Southampton (251). This lapse of time would account for the lack of references in the Sonnets to the most dramatic years of Southampton’s life. “This interval, it will be noted, coincides with the restless, tempestuous years during which Southampton, dragged at the heels of Essex, plunged from adventure to adventure, at home and on the continent, until he landed himself under sentence of high treason and attainder, a prisoner in the Tower for life” (251–52).

We know that Oxford had both wives and mistresses, so that unless we reject outright the evidence given here of homosexual inclinations, he may be seen as a bisexual. But what about Southampton? As is shown above, in his teen years Southampton was considered so cold to the female sex that he had to be encouraged to marry by the homoerotic terms of the sonnets of Shakespeare and Clapham’s Narcissus. Along similar lines is Thomas Nashe’s lascivious poem, The Choosing of Valentines (also known as “Nashe’s Dildo”), dated to 1593, and thought to be a parody on Venus and Adonis. This opens and closes with a sonnet “to Lord S” in which he is addressed as “a rose” (Green 90), and which comically details the failed attempts of a man to have sex with a woman. There is also William Burton’s translation of The Most Delectable and Pleasant History of Clitiphon and Leucippe, dedicated to Southampton in 1597, which contained a striking defense of “Greek love” (Green 145). Thus, the books dedicated to Southampton suggest that he was, as Duncan-Jones suggests: “viewed as receptive to same-sex amours” (79).

However, when in his early twenties Southampton finally married, it was to a cousin of Essex’s, Elizabeth Vernon, to whom it seems he was (relatively) faithful henceforth and with whom, as is obvious from their letters, he shared a strong love relationship and several children. According to Rowse, “His wife was the only woman we hear of in his life” (Southampton 161–62), “excepting always his mother” (71).