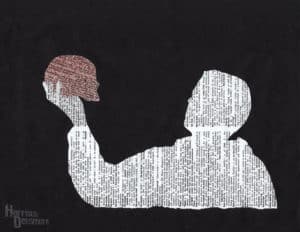

Shakespeare’s Self-Portrait: Charlton Ogburn’s Argument for Oxford

by Charlton Ogburn Jr.

This essay was posted on the Shakespeare Oxford Society (now SOF) website on September 9, 2005, and represents an enlightening summary of Ogburn’s personal perspective on why Edward de Vere, 17th Earl of Oxford, is the author “Shakespeare.” Ogburn (1911–1998) is best known as author of The Mysterious William Shakespeare: The Myth and the Reality (1984, rev. 1992), the book that remains, by common consent, the most important in the development of the Oxfordian theory after J. Thomas Looney’s founding 1920 study.

By the middle of the 19th century, outspoken disbelief in William Shakspere of Stratford-upon-Avon as the author of the works of “William Shakespeare” became a groundswell of such proportions that every biography of him must address the problem.

Why has there been this skepticism about the reputed author on the part of probably hundreds of thousands of readers? Those who share it would explain it as follows:

Shakspere the Stratfordian, according to such information as we have of him, was in his background, character, education, opportunities, reputation while alive and in the world he would have known, very nearly the antithesis of the kind of man we judge Shakespeare to have been on the testimony of his works. There is no evidence that he ever had a day’s schooling or wrote anything but six signatures of unpracticed penmanship. His parents, siblings, wife, and children were illiterate except that one of his daughters could, like her father, sign her name.

Shakspere never, so far as is known, claimed to have written any of the works later attributed to him, had no part in their publication, and, dying when half the plays remained unpublished, made no mention of them in his will and showed no interest in their survival. He is not known ever to have owned a book. His obscurity was such that at the height of his supposed fame not even the London tax collectors could discover where he lived. Until years after his death, no one we know of clearly stated that he was a writer of any kind.

As for his connection with the stage, he was never while alive listed in the cast of any play yet discovered, while the records of the reign of Elizabeth yield but one reference — and it dubious — to an actor called Shakespeare; the records of 70 municipalities in which actors performed contain no mention of his or any similar name. When he died, nothing was made over this event, supposedly so momentous to literature. His identification as the towering genius, William Shakespeare, rests on evidently studied ambiguities in the First Folio edition of the plays of 1623 and on the monument to “Shakspeare” (sic) in the church at Stratford — surely the work of outsiders — of which we first hear in the Folio. No fellow townsmen of Stratford of whom we have heard, to the fourth or fifth generation after he lived, spoke of him in any way to attribute to him a special distinction. Finally, his name was clearly not “Shakespeare, with a long “a.”

Biographers of Stratford’s now famous son, numbering in the hundreds, have been able to tell us almost nothing about him of any relevance to the masterpieces that have accounted for their interest in him. Accordingly, and in the light of the above, I am emboldened to suggest that we set aside what we have read about him and see how far we may extrapolate from Shakespeare’s works the kind of man it would have taken to write them. Possibly it would put us on the trail of what is important about the dramatist that has escaped the orthodox biographers. As we have Anatole France to remind us: “The artist either communicates his own life to his creations or else merely whittles out puppets and dresses up dolls. Carried beyond the compass of a short article, our pursuit might afford us rich new insights into the masterpieces he left us and into the workings of an incomparable creative imagination.”

Of the 37 plays of the Shakespeare canon, 36 are laid in royal courts and the world of the nobility or otherwise in the highest circles of society. The one exception, The Merry Wives of Windsor, is of them all surely the most forced and unsatisfactory. The principal characters are for the rest almost all aristocratic, even the young man who wins the beautiful girl in Merry Wives. Shylock, standing quite outside the social order, is an exception. Falstaff would seem to be another, but he is a familiar of the peerage and the chosen companion of a prince; yet even he is spurned by the new king and humiliated at the end. No other dramatist before or since has drawn his casts so predominantly from the nobility or been such a literary habitué of successive English courts.

From all we can tell, moreover, Shakespeare fully shared the aristocratic outlook of his chief characters. The populace he seems to have regarded as unfit for any share in government.

Even the rabble-rousing Jack Cade, the rebel leader, is exasperated by the light-headedness of his following. He is the only man of the people I recall in Shakespeare as being allowed to voice the grievances of his class, but the political theory imputed to him is that of a power-hungry demagogue, and he is cut down with no visible regret on the dramatist’s part.

Lower-class characters are almost all introduced by Shakespeare for comic effect and are given scant development as such. Their names bespeak their inferior status in his eyes: Snug, Bottom, Stout, Starveling, Dogberry, Simple, Mouldy, Wart, Feeble, Bullcalf, Mistress Quickly, and Doll Tearsheet. Walt Whitman, to whom the historical plays were “conceived out of the fullest heat and pulse of feudalism” by “one of the wolfish earls” or a “born descendant and knower,” lamented their author’s undemocratic views, which he held not suitable for Americans.

What many readers have found striking in Shakespeare is a compassionate understanding of the burdens of kingship combined with a romantic envy of the supposedly carefree lot of a peasant, who, free of the “peril” of the “envious court,” “sweetly … enjoys his thin cold drink” and his “sleep under a fresh tree’s shade” with “no enemy but winter and rough weather.” This would not be surprising in a writer were he more familiar with privilege than with privation.

The dramatist’s favorite sports, it would appear, were those of the nobility: hunting to hounds, bowls, falconry, and riding; one would judge him to have been a master horseman, while falconry repeatedly supplied him with images.

On the testimony of his works, Shakespeare was one of the best educated men of his century. His frame of reference was immense. In Shakespeare’s England, a two-volume study to which 30 specialists in various departments of life and society under Elizabeth contribute chapters, over 2,780 passages from Shakespeare by my estimate are quoted for their illustrative value. No other writer of the time, we may be sure, had such a range.

In language skills, Shakespeare stands alone. Where the average well-educated person is said by Max Muller to use about 4,000 words, Shakespeare is credited by Alfred Hart with a vocabulary of 17,677, twice the size of Milton’s. The number of words, mostly of Latin origin, that he introduced into English is estimated by the Oxford English Dictionary at 3,000. In a 400-page study, Sister Miriam Joseph shows “how Shakespeare used the whole body of logical-rhetorical knowledge of his time.”

We are dealing, in short, with a master of the language and a peerless enhancer of it, one whose contribution to our phraseology, according to another noted philologist, Ernest Weekley, is ten times greater than that of any other writer to any language. Persons whose opinions I trust tell us that he could and did read Greek and Roman classics in the original and that he was at home in French and Italian, and perhaps in Spanish.

The fascination the Continent had for him is evident. Of all his plays taking place in his own time, only one, the ill-favored Merry Wives again, is laid in England. All the others have Europe as their scene. Persons qualified to say tell us that he had a first-hand acquaintance with the cities of northern Italy, and there can be no gainsaying the spell they cast on him, especially the city whose spirit infuses The Merchant of Venice.

For two hundred years lawyers have been reporting Shakespeare’s proficiency in their recondite field, even of the more abstruse legal byways of his day. The law seems ever ready at his elbow to suggest metaphors. In his book The Medical Mind of Shakespeare, Aubrey C. Kail is only the latest physician to testify to the dramatist’s knowledge of the healing arts, ahead of his time.

And here the point should be made that Shakespeare does not display his familiarity with a subject when writing about that subject. He has not boned up on it to parade his knowledge, as Ben Jonson has. His learning comes out almost of itself, supplying images unrelated to the subject of conversation. Othello draws on falconry to make vivid his suspicion of Desdemona, Juliet her attachment to Romeo. To make poignant the king’s insomnia, Shakespeare calls up “the wet sea-boy falling asleep at the masthead.” It is to characterize her fun-loving Anthony that Cleopatra recalls the disporting dolphin.

As one who has practiced observation of nature since boyhood, I am struck by Shakespeare’s acuteness in it. We find him noticing that the lapwing runs in a crouch and that the cuckoo’s favorite victim is the hedge-sparrow. Combine this observation with the love and knowledge of flowers wild and domestic that is so conspicuous in Shakespeare and we have, for my money, a privileged gentleman with a country seat. We have such a leisured gentleman, too, I believe, in his equally conspicuous love and knowledge of music; he uses a hundred musical terms.

The phrase “more fell than anguish, hunger or the sea,” in which Iago is cursed upon Othello’s death, epitomized for Joseph Conrad the element so well known to him. Images of the chill sea-bottom recur to Shakespeare as they might to anyone who has known the perils of the deep. And I should be surprised if the originator of Othello’s lines and Henry V’s had not known the battlefield.

The wounded Ernest Hemingway would remember as “a permanent protecting talisman” against “the shock of combat” the lines spoken by Feeble, the young recruit, in Henry IV Part 2.

What else? Shakespeare wrote of the circulation of the blood before Harvey announced its discovery. He located the drawing power of the earth at “its very center a century before Newton had enunciated his principal of gravity. He had mountains being leveled and the continent melting into the sea two centuries before James Hutton postulated that in the absence of countervailing forces, this is indeed how they would end. Three centuries before the term was invented, his Friar Laurence enunciated the basic principle of ecology in declaring in part, “For nought so vile that on the earth doth live/But to the earth some special good doth give.” Some scholars cite anachronisms in the plays as evidence of Shakespeare’s lack of education, but chronological consistency was not a matter of concern in those days.

Let us now see if a further inquiry into the evidence will lead us to a specific nobleman of whom those things we have deduced to be true of Shakespeare will also be true, and uniquely true. We might think of ourselves as Elizabethan detectives seeking to identify the perpetrator of a crime of whom they know nothing except that he wrote the works of William Shakespeare. As such we should of course recognize that a nobleman writing for the common theatre would have been required by the mores of his class to adopt a pseudonym.

Venus and Adonis (1593) was the first poem to which the name “Shakespeare” was appended. But it had to have been preceded by less skillful, less sophisticated verse. So we should look for a nobleman who wrote youthful verse under his own name, and verse bearing a resemblance to Shakespeare’s. A nobleman well known to others around the throne yet living a life apart as the greatest poet and dramatist of his nation, beset by the incitements that goad creative genius, he might have been found contradictory, a behavioral extremist by his fellows.

He must have been an insider of the theatre (even sneaking clandestinely onto the stage!), and must have been drawn to other writers and playwrights, some of whom would presumably have known him for who he was. And, having the greatest of their art in their midst, they must have given some witness of it. We must look for a nobleman of controversial reputation, highly, if elliptically, praised by his fellow writers.

Then consider the historical plays — works in some respects greater than anything else in recorded history, as Walt Whitman called them. Surely this great body of drama could have been composed with such passionate intensity and conviction, such sure instinct, such immense evocative power, only if the past it brought to seething life made somehow an irresistible claim upon the author.

Another clue: Shakespeare’s affection for friars has often been remarked, and Catholics find overtones of an inclination toward the Church of Rome in some of the plays, notably Hamlet, in which the doctrine of purgatory seems to be accepted, despite the risks of doing so openly in the reign of Elizabeth.

Having deduced so much about the transgressor who had written Shakespeare’s works, would our Elizabethan detectives be prepared to make an arrest? Yes, undoubtedly.

They would have descended without hesitation upon the poet pronounced “most excellent of those of the court” by a critic in 1586, whom the playwright Anthony Munday (at one time our suspect’s secretary) would warmly recall as a man “of matchless virtues,” of whom Robert Greene had written that he stood in respect of other writers as Atalanta to hunters and Sappho to poets — in other words, as the best of them all.

And the reasoning we have had the detectives follow, I may add, is similar to that which in 1920 an English schoolmaster, J. Thomas Looney (who impatiently refused to change his name at a publisher’s behest) set forth in his enthralling book, “Shakespeare” Identified in Edward de Vere the Seventeenth Earl of Oxford.

Who was this Edward de Vere?

The de Veres came in with William the Conqueror. As Earls of Oxford, they were involved with all the monarchs who tread the boards in Shakespeare’s historical plays. The Second Earl stood by King John, the Third was among the barons who curbed his powers. The Sixth fought under the three successive Edwards, the Seventh beside “that black name,” Edward, Black Prince of Wales — as the French King calls him in Henry V at Crécy. The Ninth was an intimate of Richard II, with — thanks to shared faults of character — consequences fatal to both, we are told. The 11th Earl held an important command at Agincourt. The 13th Earl — “brave Oxford, wondrous well-belov’d,” as he is in Shakespeare — was a mainstay of the Lancastrian side, so clearly favored by the dramatist, in the Wars of the Roses. On the battlefield at Bosworth he helped bring down that super-villain (as Shakespeare portrays him), Richard III.

Edward, the future 17th Earl, was born on April 12, 1550, at the family’s 400-year-old seat in Essex, Castle Hedingham (of which the 80-foot keep still stands). Two of his uncles had been poets, Baron Sheffield and the well-known Earl of Surrey. Surrey introduced blank verse and, with Sir Thomas Wyatt, the form of sonnet later known as “Shakespearean.” At nine years of age, Edward matriculated at St. John’s College, Cambridge. He received an honorary degree from Cambridge University at age 14. At 16, he received another from Oxford University.

1562 saw the death of Edward’s father, John de Vere, the 16th Earl. His mother is reported to have remarried almost as hastily as Hamlet’s. Edward, at 12, became a royal ward in the household of Sir William Cecil (later Lord Burghley), who for forty years was Queen Elizabeth’s most trusted advisor. At Cecil House, close to the nexus of political power, he could have conceived “the relish and verve with which Shakespeare’s characters speak the language of ambition, intrigue, and policy,” to quote the veteran member of the House of Commons Enoch Powell, who adds that “this authentic knowledge of how men think and act at the summit of political power … could only have been drawn from experience of the political struggle.”

Here, too, while coming to know well the leading horticulturalist of the age, whom Cecil employed, Edward would have grown up in an atmosphere of rigorous intellectuality. He had the best tutors, including his maternal uncle, Arthur Golding, a noted scholar, at the time when the latter was translating Ovid’s Metamorphoses, which so strongly influenced Shakespeare. The boy proved himself a dedicated and brilliant student and went on to acquire a legal education at Gray’s Inn.

Edward had barely turned 14 when Golding dedicated a work to him with a significant reference to the “desire your honor hath naturally grafted in you to read, peruse, and communicate with others as well the histories of ancient times, and things done long ago, as also the present estate of things in our days.” A writer later dedicating a book to him declared that his “infancy from the beginning was ever sacred to the Muses.”

With his 20th birthday just behind him, Edward took part in the campaign against the Scots under the high-minded Earl of Sussex, whose siege of Hume Castle may have stood the youth in later literary service, as in describing Harfleur in Henry V.

At 21, he won first prize in a tournament against the best jousters of the day, to general astonishment. It was the first of three tournaments we know of his entering, in all of which he copped first prize. In the same year he wrote an introduction in Latin to a translation of Castiglione’s Courtier, an extraordinarily finished piece of work for one who would be a college junior today. So was his later introduction to a translation of Cardanus’ Comfort — and in both it would be easy to see a future Shakespeare.

Macaulay would write of him that “he shone at the Court of Elizabeth and won for himself an honorable place among the early masters of English poetry.” The great Elizabethan scholar, Sir Edmund K. Chambers, commenting on the dearth of distinguished poets in the generation following Wyatt and Surrey, declares that “the most hopeful of them was Edward de Vere, Earl of Oxford, a real courtier, but an ill-conditioned youth, who also became mute in later life.”

Mute only as Edward de Vere, the evidence suggests. What was young Edward’s poetry like? Some years ago Professor Louis P. Benezet of Dartmouth interlarded about 35 lines each of Oxford’s and Shakespeare’s verse and tried the amalgam on Elizabethan specialists. I know of no one who has been able to say which passages are whose without looking them up.

Whatever Chambers may have thought he meant by “ill-conditioned,” an observer of the Court wrote when Oxford was 22 that “the Queen delighteth more in his personage and his dancing and his valiantness than any other.” They may well have become lovers. The preceding year the young Earl had married Cecil’s daughter Anne when she was just past Juliet’s age. Cecil had earlier in the year been made Lord Burghley, facilitating a match between a commoner’s daughter and the premier earl of the land. The marriage, which would prove the single greatest misfortune in the lives of all three, joined in lasting close relationship two utterly unlike men, one aristocratic, mercurial, poetical, and contemptuous of money, the other a self-made member of the new middle class, materialistic, crafty, hard-working, a devoted public servant — two men who outshone all their contemporaries in their respective fields, if we may trust the trail that led us to the Earl of Oxford.

We might say that the principals of Hamlet have now taken their places on stage. That the Prince was the dramatist depicting himself seems to me unmistakable, and that Polonius was a caricature of Burghley has long been recognized. Even Chambers asks if “Polonius [can] have resembled some nickname of Burghley” and says that “Laertes is less like Robert Cecil than Burghley’s elder son Thomas.” And I am by no means the first to see Elizabeth and Leicester in Gertrude and Claudius. Leicester, a “lecherous villain” in more eyes than Oxford’s, was the nearest to a husband Elizabeth ever had, and if he did not murder an earlier mate of hers to win his position, he was widely believed to have murdered his own to do so. Scandalous rumor also viewed him as the poisoner of the noble Earl of Sussex, who seems to have stood somewhat in loco parentis to de Vere after the Scottish campaign. Significantly, Leicester won custody of the boy Edward’s inheritance, the Oxford estates.

If de Vere saw himself as Hamlet in the retrospect of later years, he may probably be pictured in youth, when he stood high in Elizabeth’s favor, as the male protagonists in the early comedies: Berowne “the merry, madcap lord,” Bertram with his glaring faults, and Benedick, and Faulconbridge in King John — high-spirited gallants all, with a taste for soldiering.

The penchant for “lewd companions” of which Burghley accused his son-in-law, probably referring to actors and writers, comes out in another of these gay young blades, Prince Hal, whose participation in the hold-up staged by his cronies at Gad’s Hill on the highway between Rochester and Gravesend is simply a replay of the one staged by Oxford and his followers at the same place on the same highway when he was 23.

At 25, Oxford obtained from the Queen the permission he had long sought to visit the Continent. Most of his fifteen months’ stay was spent in the Italian cities later to be the scenes of those happy Shakespearean comedies. Evidently he was captivated by the country. He was drawn, too, to the Church of Rome, though apparently not greatly interested in religion. We know that, like Bertram in All’s Well, he came back with Italianate ways, for he was chided about this by Gabriel Harvey, to the point of scandal. But Harvey also avowed of him:

For gallants a brave mirror, a primrose of honor,

… a fellow peerless in England.

Not the like discourser for Tongue and Head to be found out …

All gallant virtues, all qualities of body and soul.

On his trip back from Europe — during which his ship, like Hamlet’s when bound for England, was captured by pirates — Oxford received tidings that bowled him over. He had rejoiced while in Italy at the delayed news that his wife had borne him a daughter. Now he evidently heard reasons to suspect that the child was not his. The conveyor of this intelligence seems to have been a hanger-on of Oxford’s, a fellow of treacherous instincts named Yorke (Iago?).

In turmoil of mind, Oxford alienated himself from his wife and estranged himself from her father. The separation was to last for five years. In the interval he had an affair with a brunette minx newly arrived at Court, Anne Vavasour, in whom we may see both Rosaline of Love’s Labour’s Lost and the dark wanton of the Sonnets. By her he had a son, with the immediate consequence that he and Anne were clapped into the Tower. (Those who served Elizabeth served a jealous monarch.) Another consequence was a sword-fight between Oxford and Anne’s kinsman, Thomas Knyvet. “This was the signal for war between the two houses,” Albert Feurillerat wrote in 1910. “As at another time in Verona, the streets of London were filled [surely an exaggeration] with the quarreling clamors of these new Montagues and Capulets.”

Though the Countess of Oxford presented her husband with three daughters who survived infancy, all of indubitable legitimacy, she lived only seven years after their reconciliation, such as it was, dying in 1588 at age 31. If we may accept the testimony of the plays, Oxford castigated himself for his treatment of her. Othello, Leontes in The Winter’s Tale, Posthumus in Cymbeline, and Claudio in Much Ado About Nothing are all persuaded by a cynical third party, on the flimsiest and most unconvincing grounds, of the infidelity of the young women to whom they are married or affianced, and they angrily reject them. Angelo in Measure for Measure rejects Mariana with as little ceremony and reason. Of the others, three entertain thoughts of murdering their erstwhile loves — Othello actually does and Leontes thinks he has. All are overwhelmed by remorse. Hamlet rejects Ophelia somewhat less brutally, on grounds of general moral repugnance, but the consequences are as fatal for her as for Desdemona.

Obviously the theme gnawed at the dramatist. One could understand why, if Oxford came to believe Anne was as chaste and noble as Desdemona, Hermione, Imogen, Hero, and Mariana. But the opposite was evidently the case. Long before Oxford’s suspicions were aroused, Anne and her father were worried to death that he would not accept the child. So why this pitiless remorse? Did he discover that poor Anne was more sinned against than sinning?

Or perhaps … both Bertram in All’s Well and Angelo in Measure for Measure were brought to consummate their marriages by being led to sleep with their respective partners under the misapprehension, fostered by darkness, that the assignation was with a female more enticing to them. Singularly enough, there are two independent reports that the same was true of Oxford. As one of them had it, “the father of Lady Anne by stratagem contrived that her husband should unknowingly sleep with her, believing her to be another woman, with the result that a child was born to the couple.”

During the 1580s the menace from Spain was growing. In 1584, Elizabeth finally sent an expeditionary force to the aid of the Protestants in the Low Countries. Oxford was named commander of the horse but soon returned for unknown reasons (perhaps repining with Othello, “Farewell the plumed troop …”). For the second time, his ship was captured en route to England by pirates. It must have come as a relief when on his next venture upon the Channel, in 1588, the month after his wife’s death, he was the attacker, going into combat with his own vessel against the Spanish Armada.

Ten years earlier, in 1578, when Oxford was 28, Gabriel Harvey had addressed him in Latin hexameters with these words: “Thy splendid fame demands even more than in the case of others [Elizabeth, Burghley, and Leicester, whom Harvey also addressed] the services of a poet possessing lofty eloquence.” Terming Oxford’s introduction to The Courtier “even more polished” than the writings of Castiglione himself, Harvey called upon it to “witness how greatly thou dost excel in letters. Many Latin verses of thine [all lost] have I seen, yea even more English verses.” Probably at the instigation of Oxford himself, who yearned for military exploit, he exhorted him to “throw away the pen, throw away bloodless books …. Now is the time to sharpen the spear and to handle great engines of war.” Harvey wound up by declaring, “Thine eyes flash fire, thy countenance shakes spears.”

One suspects that Oxford’s zeal for military honor — which the example of his cousins, the “fighting Veres” Francis and Horace, would have done nothing to cool — was thwarted by the Queen herself. Evidently she had other plans for him. In 1586 she made him a grant of the immense sum of £1,000 annually, to be paid by the Exchequer with no accounting required. This allowance, confirmed by King James, would continue for the remaining eighteen years of his life. This would have enabled him to support acting companies and, as Shakespeare, to finance his writing for the stage, beginning with the historical plays. These could be expected to rally the nation in the face of the menace from Spain and to harrow it with the dreadful consequences they portrayed of disunity and disputed succession.

Oxford could surely have used the funds. From the 12-year-old who after his father’s funeral had ridden out of Essex into London “with seven score horses all in black” (or so it was reported), he had been reduced to three servants. Like Jaques in As You Like It, he had sold his lands to see other men’s, and like Timon of Athens he, and those he favored, had lived rather too well on his estate. “Let all my land be sold!” Timon grandly declares when none is left. Oxford was the most generous literary patron of the age. As the poet George Chapman wrote, he was “valiant, learned, and liberal as the sun.”

Both the 15th and 16th Earls of Oxford had maintained a troupe of actors, and the 17th had at least one during most of his life. In addition, he took a lease on Blackfriars Theatre and transferred it to his secretary, John Lyly, who used it to rehearse a boys’ company for performances at Court. Lyly’s highly successful novel Euphues had, he said, been “sent to a nobleman to nurse, who with great love brought him up for a year, so that wheresoever he wander he hath his nurse’s name in his forehead.” That the sequel was dedicated to Oxford should leave no doubt as to whose stamp was on Euphues.

When we hear Hamlet addressing the actors on their craft, may we not hear Oxford addressing his own, and with an authority even those giants of the theatre, Burbage and Kempe, would have respected? I mention those two because they were stars of the Lord Chamberlain’s company, which from the time of its formation in 1594 was the vehicle for the introduction of Shakespeare’s plays. And there are grounds for believing that it was Oxford, as hereditary Lord Great Chamberlain, rather than the holders of the title Lord Chamberlain, who managed the affairs of the company.

Not long after the celebration of the victory over the Armada, in which Oxford may have been one of the peers bearing the canopy over the Queen (“Were’t aught to me I bore the canopy,” we read in Sonnet 125), Oxford largely dropped from public view. This led the poet Edmund Spenser, if I am right, to lament in 1590 that

the man whom nature self had made

To mock herself, and truth to imitate,

… under mimic shade,

Our pleasant Willy, ah! is dead of late.

Earlier in the year in one of the sonnets prefacing The Faerie Queene, Spenser had paid Oxford a remarkable tribute, speaking of “the love which thou doest bear, To th’Heliconian imps, and they to thee, They unto thee, and thou to them most dear.” (Mount Helicon was sacred to the Muses, and a meaning of “imp” at the time was “scion,” especially of a noble house.) The next year he received the first of two dedications of books on music by the former organist and choirmaster of Christ Church Cathedral in Dublin, who declared that “using this science as a recreation, your lordship have overgone most of them that make it a profession.”

Were the plays we know as Shakespeare’s written by a nobleman of the Court and known to have been written by him, they would have been scrutinized for the light they might throw on personages and events at the highest level — and this the Queen, Burghley, and others would not have tolerated. Those performed or printed (by pirates) before 1598 had no author’s name associated with them. Then in that year Francis Meres named “Shakespeare” as among the best for comedy and listed twelve plays to his credit. (About that time William Shakspere of Stratford began to make his investments of huge sums of money.) In that same year, too, addressing one “whose silent name one letter bounds” — surely Edward de Vere — the poet John Marston plainly took us to the nub of the matter in writing:

Far fly thy fame,

Most, most of me beloved …

Thy unvalued worth

Shall mount fair place

when Apes are turned forth.

In Sonnet 81, the poet recognizes that “I, once gone, to all the world must die.” In 1603 — thirteen years before Shakspere would be buried — he was in fact facing the end, for in Sonnet 107, unmistakably referring to events of that year and surely written no later, he says that “death to me subscribes.” Oxford died the next year, on June 24, 1604.

In arguing, with no good evidence, that some of Shakespeare’s greatest plays were written after 1604, orthodox scholars ignore Sonnet 107’s plain statement, as they do the circumstances of the Sonnets’ publication in 1609, which made it doubly clear that the author was dead, for he had no hand in it and was unable to provide a dedication. That was left up to the printer, who referred to the poet as “ever-living,” a characterization never applied to persons actually alive. Moreover, some of Shakespeare’s plays, displaying the highest level of cultivation, had clearly been written by the late 1580s, before Shakspere of Stratford can be imagined ever to have been in London or to have spoken an English intelligible there.

Hamlet, with very nearly his dying breath, cries: “O God, Horatio, what a wounded name, Things standing thus unknown, shall live behind me! If thou didst ever hold me in thy heart, Absent thee from felicity awhile, And in this harsh world draw thy breath in pain, To tell my story.”

My guess is that it was Oxford’s cousin, Horace Vere, indisputably the model for Horatio, who in the year of Oxford’s death arranged to have Hamlet printed from the author’s manuscript (a novelty in the case of a Shakespeare play), with the royal coat of arms of the Plantagenets on the first page, as befitted the passing of a prince. It was probably the best he could do, bound as he was by strictures of secrecy, to see that his cousin’s story was told.

The rest is up to us.

Membership dues cover only a fraction of our budget, including all our research, preservation and programming. Please support the SOF by making a gift today!

Blue Boar Tavern: Wassail Q&A

Tuesday Dec. 17, 8pm E / 5pm P

Sign up below for event invites!