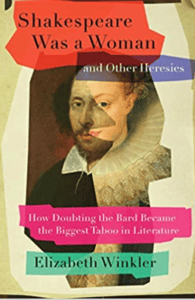

Patrick Sullivan reviews Shakespeare was a Woman and Other Heresies by Elizabeth Winkler

Elizabeth Winkler’s new book was published by Simon and Schuster on May 9th and is garnering spectacular praise.

No Frail Woman, She

Review by Patrick Sullivan

Elizabeth Winkler’s book, Shakespeare Was a Woman and Other Heresies: How Doubting the Bard Became the Biggest Taboo in Literature, might well be the best book out there now as an authorship primer. It’s well organized and written, detailed, but not to death. No curse of knowledge to it. The author can truly claim to know how to do the Shakespeare Authorship Question.

With the publication of Shakespeare Was a Woman and Other Heresies, Elizabeth Winkler has arrived at the academic tea with a full pail of milk with which to douse some of the biggest names in Shakespearean expertise. It’s worth the price of the book just to read her interview with Sir Stanley Wells, Chairman of the Shakespeare Birthplace Trust, who insists time and again that he can’t remember reading any of the references he has in the past described as ‘cryptic’, to Shakespeare in the biographical literature that is supposedly his life’s work. Willobie His Avisa; “I’ve never studied [it].” Thomas Vicars’s 1628 mention of “that poet who takes his name from shaking and spear.”; “I don’t remember that.” Oenone and Paris, the 1594 parody of Shakespeare’s Venus and Adonis; “I don’t remember it, actually.” Joseph Hall’s reference to a poet hiding like a cuttlefish in a cloud of ink, shifting his fame onto another’s name; “No, I’ve forgotten it.”

Winkler says of this performance; “I felt as though I was cross-examining a witness who kept claiming amnesia.” She shows great compassion for a man who had devoted his life to Shakespeare, as a matter of faith and was hard-pressed now to give it up.

Then Wells began offering ad hominems against anti-Stratfordians. Alexander Waugh was “a wicked man,” later “an evil man.” Anyone who questions the authorship suffers from “psychological aberration.” Derek Jacobi and Mark Rylance: “They’re both bonkers.” But what really startled Winkler was when Wells said in a discussion of Sonnet 136 (the famous “My name is Will” sonnet), “I would have thought he’s simply saying, ‘Let me remain anonymous.’ Something as simple as that.” Later, he offers: “Shakespeare somehow managed to lead this sort of double life, [between Stratford and London]….That is not true of the other dramatists of the time, all of whom I think it’s fair to say are based in London.” Cognitive dissonance, thy name is Wells!

There is much more to open one’s eyes at, in this book. I particularly was intrigued to read that Alexander Waugh believes that Sonnet #81: Your name from hence immortal life shall have,/Though I once gone, to all the world must die:/The earth can yield me but a common grave,/When you entombed in men’s eyes shall lie is directed at the Stratford man. After all, the fair young man is never named.

In his magnum opus, Knowledge and Decisions, the economist Thomas Sowell pointed out that the standards for being able to say “I know how to ….” (do something), are much higher in lower status professions than in more exalted ones. His example being that, for a farm boy to show he knows how to milk a cow he has to go into the barn with an empty pail and come out with one filled with milk. Sowell contrasts that with a criminologist who does not have to go into a community and actually lower the crime rate, but merely get a paper published in a journal with a theory that will appear plausible to other academics who have, likely, the same educational background.

Winkler knows how to do the SAQ.

Membership dues cover only a fraction of our budget, including all our research, preservation and programming. Please support the SOF by making a gift today!

Blue Boar Tavern: Wassail Q&A

Tuesday Dec. 17, 8pm E / 5pm P

Sign up below for event invites!