Some observations on the Shakespeare authorship debate between Sir Jonathan Bate and Alexander Waugh: “Who Wrote Shakespeare?” (September 21, 2017, Emmanuel Centre, London)

by Steven Steinburg

January 30, 2018

The full debate may be viewed here on YouTube.

(Note regarding quotations and quotation marks in this article: For the purpose of clarity, direct quotations are either set apart or indicated with double quotation marks. Single quotation marks indicate approximate or paraphrased quotations.)

In consideration of the constraints of the debate format and the small time allotted, I commend Alexander Waugh. A certain gratitude must be extended Sir Jonathan for his unintended exposure of the farce that marches under the banner of “professional Shakespeare scholarship.” This critique contains a partial transcription of the debate to which my commentary is added. The transcription is my own. Errors are possible.

Moderator: Hello and welcome. We’re here tonight to debate the question of Shakespeare’s authorship, and a question that is so explosive, and potentially radical, that it’s very rare for the academia, the grove of academia, to discuss it at all. So we are very honored to have with us Sir Jonathan Bate, the preeminent Shakespeare scholar, who will be making the case for the man from Stratford as the author of the plays and poems. Sir Jonathan is professor of English Literature at Oxford University. He has published on Shakespeare and Ovid, on Shakespeare and his collaborators, on Shakespeare and the romantics. He edited the Royal Shakespeare Company Complete Works, a monumental book as well as a best seller of sorts. And he is, his influence is such that his Arden edition in 1995 of Titus Andronicus totally revised our feelings about the play.[1] He is going to really make his case for Shakespeare. And on the other hand, we have here Alexander Waugh . . . the Chairman of the De Vere Society, who is in demand around the world as a spokesman for the theory that the 17th Earl of Oxford, Edward de Vere, was the author of Shakespeare’s work. Waugh himself is a distinguished editor of the . . . forty-three-volume complete works of Evelyn Waugh, his grandfather. He is the author of such modestly titled books as God, Time, and also a biography of the Wittgenstein family. He is also the author of a very pertinent, Shakespeare in Court which is published on Kindle. And the two, I believe, are great friends, and never discuss the Shakespeare question. They will each speak for fifteen minutes. Then they will rebut one another’s arguments, and answer each other’s arguments. And then we shall move to questions from the floor. So, I shall light the fuse and stand well back. Alexander Waugh.”

I am skipping over Alexander Waugh’s monologue (respectfully). What follows immediately below is my transcription of the entirety of Professor Bate’s fifteen-minute monologue with a few short comments inserted in brackets and at footnotes. My detailed commentary follows thereafter. Bate says:

Thank you, Hermione [moderator]. This is a debate. Now the key to the spirit of the debate is this: Are you prepared to change your mind? Do you believe in evidence-based argument? Or do you prefer coincidences, conspiracies and cryptograms, hidden codes. I am here to speak for historical evidence, for truth, for fact. But in our post-truth world, I know that I will not persuade the believers in the ‘fake news’ that Shakespeare did not write Shakespeare, to change their minds. I will not persuade the cultists of Oxford who have put bits of paper on your chairs. [Negative audience reaction] Cultists allow emotion and wishful thinking to rule over evidence and common sense. I am here to address the agnostics among you. The true believers in the false story are a lost cause. But I’m rather fond of them. They add to the gaiety of nations. [Audience laughter] Especially Alexander Waugh. Alexander is a dear friend. But you must know two things about the Waughs. Number one, they love to be contrarians. His father Auberon was one of our great contrarians. Number two, they love an aristocrat. [Audience laughter] Read his grandfather’s novels.

Now, here’s the most important fact of tonight. Nobody, nobody, for 240 years after Shakespeare’s death expressed any doubt that William Shakespeare, the actor from Stratford upon Avon, was the author of the plays and poems. The first person to doubt it was a woman called Delia Bacon. [Negative audience reaction] She ended up in a private lunatic asylum. [Negative audience reaction] She thought that the author was Francis Bacon. Bacon? I wonder why she thought that. And then over the years subsequent proposals came in. Among the dozens of candidates we’ve had, 1st Earl of Salisbury, the 2nd Earl of Essex, the 3rd Earl of Southampton, the 5th Earl of Rutland, 6th Earl of Derby, the 7th Earl of Shrewsbury, the 8th Lord Mountjoy, the 17th Earl of Oxford, the bastard son of the Earl of Hertford and Lady Katherine Grey, and not to mention Queen Elizabeth and King James.

Everybody loves an aristocrat. Why, at some point in the 19th century, did people start thinking an aristocrat might have written the works of Shakespeare? Well there’s a simple answer to that. It’s because serious biographical work about Shakespeare began to emerge in the late 18th century and we found his life is rather boring. He made money out of his plays. He was shrewd enough, unlike other playwrights who merely got paid on a piecework basis, he was shrewd enough to become a shareholder with the actors and take a share of the box office profits, and it allowed him to buy a big house back home in Stratford. Now, in the 19th century, the romantic period, everyone wanted great authors to be glamorous. The most famous author of the age was Lord Byron. So they wanted Shakespeare to be a glamorous aristocrat like Lord Byron. Alas, though, he wasn’t. The true story of Shakespeare is a story about how you can come from the middle classes and with a grammar school education, no university education–Shakespeare was much mocked for not having a university education–you can become a great writer.

Right, let’s begin with the facts. In the will of William Shakespeare, Shaksper, Shaxberd–people were very, very relaxed about spelling in those days–in the will of the man from Stratford he leaves mourning rings to his friends, John Hemmings, Henry Condell, and Richard Burbage, the leading actors of his acting company, the Lord Chamberlain’s, later the King’s Men. On his tomb, he is described as a great writer, praised for his wit. He is said, on his funeral monument in Stratford church, to combine the wisdom of Socrates with the art of Virgil. That monument was transcribed within a year of his death. It’s alluded to in poems of praise. It’s copied by pilgrims going to Stratford. From the 1620s onward, people are going to Stratford saying this is the home of the great writer. His monument, of course, shows him holding a pen and paper. Other writers in his lifetime praised him, spoke about his writing techniques. Ben Jonson, fellow dramatist. Shakespeare acts in many of Jonson’s plays. We have the cast lists of half a dozen Jonson plays and Shakespeare is acting there. Jonson, when he goes north to meet the writer Drummond, talks about Shakespeare’s writing techniques. He also does so in his private notebooks. Others too. Francis Beaumont, William Camden, John Davis of Hartford, Sir George Buck, Leonard Digges, Francis Meres, the Cambridge author of the Parnassus plays, they all talk about Shakespeare as a writer.

Now the anti-Stratfordians will say, where then are his manuscripts? Why don’t we have the manuscripts to prove the signatures that survive of William Shakespeare are the same? Unfortunately, no manuscripts of any of the 600 published plays by any of the authors from the period survive. Once a manuscript went to the printer the printer either recycled it or threw it away. However, a tiny number of theater manuscripts survive because they were plays that weren’t performed. One of those was a collaborative play. Collaboration in theater, then as in television and film now, the art of writing was collaborative art. Collaboration was the norm. Shakespeare contributed a scene to a collaborative play about the life of Sir Thomas More that was banned because it was too politically sensitive. And handwriting experts have looked at the hand in that manuscript, and I’ve held [it] in the British Library, and found six particular features of handwriting which they then compared with Shakespeare’s signatures and with the handwriting of 250 other writers from the period and there are six features that only match Shakespeare’s.

Letters. People say, why don’t we have Shakespeare’s letters. Well, we do have a couple of Shakespeare’s letters. They were appended to his poems, the poems which made his name, Venus and Adonis and The Rape of Lucrece, and they are rather servile. They’re saying please give me patronage my Lord Southampton. The idea that an earl like Oxford, one of the great earls of the land, would have written these servile flattering letters to a mere junior aristocrat, a twenty-year-old whippersnapper like Southampton is inconceivable. The theory about Oxford…or some other aristocrat, having to write under a pseudonym because they were worried about being associated with the theater is frankly bizarre.[2] The earl of Oxford was patron and sponsor of a theater company, Oxford’s Men, they toured in the provinces in the 1580s and 90s. If Oxford was proud of his involvemen with the theater why didn’t he write the plays for Oxford’s men?[3] If he was ashamed, then why did he have an acting company? We hear that Shakespeare’s father was illiterate. It’s funny then that there’s a will in which someone leaves him some books, a strange thing to leave to an illiterate man. Why were there no books in Shakespeare’s will, well, look at the wills of Hayward, Beaumont, Fletcher, Massinger, Middleton, Webster, Ford, Marston. No books in any of their wills. People didn’t, on the whole, specify books in their wills.

Now, one of Alexander’s big arguments is that the person who wrote the plays must have gone to Italy because there’s lots of detail about Italy in the plays. Those would be plays where two of them are set in Venice and there’s no single mention of a canal. [Slight audience laughter] There are certain details about Italy that seem to be authentic, but equally Ben Jonson never went to Italy, and yet in Volpone he knows the location of the portico to the Procurata. John Webster never went to Italy, yet in the Duchess of Milan,[4] he knows the location of a lane behind Saint Mark’s Church. You can pick up knowledge from books and conversations. We might just as well say, how did Shakespeare know about the details of the platform at Elsinore in Hamlet? The answer would be that three of his fellow actors in the acting company, Bryan, Pope and Kemp, went to Elsinore and told him about it. The earl of Oxford never went to Elsinore.

How could this humble middle-class boy from the grammar school have known so much about aristocratic households? According to John Dryden, the 17th century writer much closer to aristocratic households at the time than we are, he writes that Shakespeare understood very little of the conversation of gentlemen. Shakespeare was actually pretty useless at representing what aristocratic households, with hundreds of retainers were really like. Just have a look at Romeo and Juliet where the character of Capulet, leading aristocrat, his daughter’s about to be married to Paris the kinsman to the prince, he’s down in the kitchen speaking to the staff. No, that sort of thing didn’t happen. Shakespeare didn’t know about Italy. He didn’t know about aristocratic households. What did he know about? He knew about wool trading and leather manufacture. His father was a glovemaker. The plays refer to calfskin, sheepskin, lambskin, foxskin, dogskin, deerskin, kidskin, neat’s leather, leather for a bridle. Shakespeare was above all a countryman. Look at the countryman in The Winter’s Tale speaking about tods equaling pounds and shillings for wool. This is countryman’s language. Six hundred plays from the period survive. The only ones that mention Warwickshire and Gloucestershire are those by Shakespeare.

There’s a little problem for the argument about earl of Oxford writing Shakespeare. He died in 1604. A large number of Shakespeare’s plays were written thereafter. In the plays that Shakespeare wrote in the reign of Queen Elizabeth he always talks about England because she was Queen of England. In the plays he wrote for King James after James came to the throne in 1603 he wrote about Britain because King James wanted to unite England and Scotland into Britain. Macbeth, King Lear, and Cymbeline are specifically linked to the Jacobean project. Similarly, in 1608 Shakespeare’s acting company acquired an indoor playhouse so that, instead of acting outside in natural daylight they had to have candles. So, in his late plays he starts introducing act divisions, the five-act structure so there was a break so the candles can be replaced. Oh, that Earl of Oxford was a clever chap. He realized that four years after his death there would be an indoor theater. So he must have written some plays like The Winter’s Tale and The Tempest with act breaks just preparing for it. And then, most interestingly of all, at the end of Shakespeare’s career he’s got to decide who’s going to take over as the leading playwright of the acting company, and he chooses a young dramatist called John Fletcher who came on to the scene in 1607. In Shakespeare’s last three plays, The Two Noble Kinsmen, Henry the 8th, and the partially lost play Cardenio, are co-written with Fletcher. For 150 years scholars have been able to identify different linguistic fingerprints of Shakespeare and Fletcher. Shakespeare says ‘you’. Fletcher says ‘ye’. Shakespeare says ‘them’. Fletcher abbreviates to em, apostrophe e m [’em]. Feminine endings and unstressed syllable at the end of the line. Very different patterns in Shakespeare and Fletcher. So, we know as Shakespeare and Fletcher sat down to write Henry the 8th and The Two Noble Kinsmen together, which scenes were Shakespeare and which scenes were Fletcher. I’m struggling to imagine how Oxford did that from beyond the grave, let along how he collaborated with Fletcher in the play of Cardenio which was based on Don Quixote, 1605, after Oxford’s death, and indeed has allusions to the 1612 English translation.

I still want to celebrate the work of the anti-Stratfordians and thank them because there is a long history whereby forgery and fiction has assisted the work of true scholarship. Because we get asked hard questions as scholars and we have to find better answers. So, it was there were two interesting scholars in California called Elliot and Valenza, one a statistician and one a computer scientist who became convinced that Shakespeare couldn’t have been Shakespeare. But they developed well-established techniques of linguistic fingerprinting. Everybody has their own linguistic fingerprint. The little turn of the phrase, the little choices we all make. And they ran through their computers, not only the entire corpus of surviving drama of the period, Shakespeare plays, but also the surviving writings of the Earl of Oxford and all those other candidates. And they came to the conclusion that it is a mathematical certainty that none of those other candidates could have written the work of Shakespeare. But, thanks to those advancements in stylometric study we now know things we didn’t know before.

For instance, we know when Shakespeare, early in his career wrote Titus Andronicus he collaborated with George Peele. And we know that because Peele used ‘brethren’ as the plural of brothers and Shakespeare used ‘brothers’, and we know from that: Peele wrote the first act and Shakespeare wrote the rest. So, it’s something to be celebrated that we have these debates because eventually the truth will out! [Sits down. Applause.]

It is important to be clear about who ‘Sir Jonathan Bate’ is and to appreciate how highly esteemed he is in the periodical press and in the establishment. He is a distinguished Professor of English Literature at Oxford University. He has published extensively on the subject of Shakespeare. He was knighted by the Queen of England for his scholarly accomplishments. A handful of his peers speak with equal authority on the subject of Shakespeare, but none speak with greater authority. Noting Bate’s distinguished credentials, the rarity of the event, the evidently well-informed audience at the event, and the notoriety the debate is likely to receive among followers of the Shakespeare authorship question, the natural expectation must be that Bate would come armed with the very best arguments.

I propose two primary take-aways from this debate. First, for me at least, Bate’s arguments did far more to expose the defects in the Stratfordian case than to uphold it, demonstrating once again that, for Stratfordians, it is counter-productive to debate the authorship question. Second, Bate’s performance raises serious concerns about his judgment, competence, and scholarly standards. To be clear, I do not accuse Bate of willful dishonesty. I do accuse him of inadvertent dishonesty and astounding self-deception.

Taking the High Ground?

Bate began his presentation with the presumption that he occupies the high ground of ‘historical factuality, truth, and scholarly objectivity’. This, ironically, was tucked into a blatant extended ad hominem argument aimed at all who do not accept William Shakspere’s authorship. Amazingly, in his follow-on remarks Bate vigorously denied using ad hominem arguments. This is remarkable in itself and justifies an aggressive dissection of Bate’s arguments and statements. I quote from the opening words of his presentation:

This is a debate. Now the key to the spirit of the debate is this: Are you prepared to change your mind?

It would have been wonderful, at this point, if someone had interrupted to direct the question back to Jonathan Bate to ask: ‘Are you suggesting, Professor Bate, that you are prepared to change your mind, or does that spirit only apply to those who disagree with you?’ I don’t know what he would have said, but I think it would have been interesting, because, in what he says next, it becomes absolutely obvious that he is not playing in that “spirit”. From this hypocritical opening, the pretentiously fair and open-minded Professor Bate immediately sets about to define all those who disagree with him within a set of ad hominem generalizations which he grounds in a logical fallacy as follows:

Do you believe in evidence-based argument? Or do you prefer coincidences, conspiracies, and cryptograms, hidden codes.

This is what’s known as a false dilemma or straw man argument. As Bate has defined the proposition you are either: A – someone who “believes in evidence-based argument”; or you are B – someone who “prefers conspiracies” etc. The fact of the matter is that you can “believe in evidence-based argument” and remain skeptical of that same “evidence”. You may reject the evidence without, ipso facto, being someone who ‘prefers coincidences, conspiracies, and cryptograms, hidden codes.’ Here again, it would have been fortunate if someone had raised an objection. Unfortunately, the rules for this debate did not allow anyone to interrupt and object. Bate continued unabated:

This is what’s known as a false dilemma or straw man argument. As Bate has defined the proposition you are either: A – someone who “believes in evidence-based argument”; or you are B – someone who “prefers conspiracies” etc. The fact of the matter is that you can “believe in evidence-based argument” and remain skeptical of that same “evidence”. You may reject the evidence without, ipso facto, being someone who ‘prefers coincidences, conspiracies, and cryptograms, hidden codes.’ Here again, it would have been fortunate if someone had raised an objection. Unfortunately, the rules for this debate did not allow anyone to interrupt and object. Bate continued unabated:

I am here to speak for historical evidence, for truth, for fact. But in our post-truth world, I know that I will not persuade the believers in the ‘fake news’ that Shakespeare did not write Shakespeare, to change their minds, I will not persuade the cultists of Oxford who have put bits of paper on your chairs. Cultists allow emotion and wishful thinking to rule over evidence and common sense.

Once again, an interruption and objection would have been warranted. According to Bate, if you believe that Shakspere was not Shakespeare, you are a ‘believer in fake news’, or the equivalent, and you are not on the side of ‘historical evidence’, ‘truth’, or ‘fact’. Professor Bate reserves that side for himself and those who agree with him. His quip about “fake news” is cute. It is timely. Considering what that phrase invokes at this time, it is deeply insulting. So, if you believe that Oxford wrote Shakespeare you are a ‘believer in fake news’, a ‘cultist’ who ‘allows emotion and wishful thinking to rule over common sense.’ Bate doesn’t say, ‘you might be.’ He doesn’t say ‘some are.’ In a ‘friendly’ debate, a bit of good-natured mocking will hardly be avoided, but that such extended insulting generalizations are not “in the spirit of fair-minded debate”, is, I assume, self-evident. It is not evident to Professor Bate who, in the end, flatly denies having made any ad hominem arguments, except, as he explains, on another occasion when it was warranted, where the person in question was a Holocaust denier. Oblivious to dubious and hypocritical manners, Bate sets forth his ad hominem argument:

I am here to address the agnostics among you. The true believers in the false story are a lost cause. But I’m rather fond of them. They add to the gaiety of nations. Especially Alexander Waugh. Alexander is a dear friend.

To the “agnostics” (neutral observers and potential converts), Bate offers hope of salvation. To the unconvertable he offers a toothy ‘fondness’ dripping with condescension. This categorical insult is applied “Especially” to his “dear friend”, Alexander Waugh. Evidently Professor Bate believes that insults coated in fondly humorous affection are not insults. And he’s not done:

But you must know two things about the Waughs. Number one, they love to be contrarians. His father Auberon was one of our great contrarians. Number two, they love an aristocrat. Read his grandfather’s novels.

A “contrarian” is someone who is unreasonably disagreeable. To “love an aristocrat” is similarly unreasonable. The “Waughs” are unreasonable people and their “love” of aristocrats is a manifestation of snobbery. I think that is the gist of Bate’s argument about “Alexander” and “the Waughs” and, again, all disbelievers. And of course, while these characteristics may be regarded with fond amusement, they are not compatible with ‘serious scholarship’. These, notably, are the “two things” we “must know . . . about the Waughs”. This is one of Bate’s major arguments. He digresses slightly:

Now, here’s the most important fact of tonight. Nobody, nobody, for 240 years after Shakespeare’s death expressed any doubt that William Shakespeare the actor from Stratford upon Avon was the author of the plays and poems.

This is a simple but blatant fallacy, for the ‘fact’ that Bate asserts is (as Waugh later responds), quite disputable. Moreover, as a point of rhetorical clarity, it is by no means self-evident that this could or should be “the most important fact of the night”. And, it should be noted that the ‘fact’ Bate asserts is demonstrably not factual. Continuing his major ad hominem theme, Bate says:

The first person to doubt it was a woman called Delia Bacon. She ended up in a private lunatic asylum. She thought that the author was Francis Bacon. Bacon? I wonder why she thought that. And then over the years subsequent proposals came in.

That Delia Bacon was the first doubter is, as Waugh responds, debatable. And what about Colonel Joseph C. Hart (1848), who preceded Delia Bacon? Was he not a doubter?[5] But, as Bate argues, if you do “doubt it”, you must be like Delia Bacon, i.e., literally a “lunatic”. And, if you have an aberrational ‘love of aristocrats’, like the Waughs do, like all anti-Stratfordians do, well, he’s just saying, and somehow, again, this should not be taken as an insult and should, somehow, be taken as an argument for Shakspere’s authorship. Driving the point home, Bate continues:

Among the dozens of candidates we’ve had, 1st Earl of Salisbury, the 2nd Earl of Essex, the 3rd Earl of Southampton, the 5th Earl of Rutland, 6th Earl of Derby, the 7th Earl of Shrewsbury, the 8th Lord Mountjoy, the 17th Earl of Oxford, the bastard son of the Earl of Hertford and Lady Katherine Grey, and not to mention Queen Elizabeth and King James. Everybody loves an aristocrat.

This obviously ad hominem argument is now curiously redundant. In other words, if you ‘disbelieve’ Shakspere’s authorship, it goes without saying that you ‘love aristocrats’ and you are a snob. No exceptions! Having begun with such a conclusive and redundant (but fallacious) argument, Bate might as well have declared himself the winner and said, ‘Good evening.’ If I were not familiar with Stratfordian argumentation I would have been surprised to see someone of Bate’s stature resorting to this sort of sophomoric slip-shod argument. I was not surprised. His cheap shot at Delia Bacon garnered him a well-deserved negative reaction from the audience. Bate asks:

Why, at some point in the 19th century, did people start thinking an aristocrat might have written the works of Shakespeare? Well there’s a simple answer to that. It’s because serious biographical work about Shakespeare began to emerge in the late 18th century and we found his life is rather boring.

I fear it will be overlooked (and I shall assume that Bate has overlooked it), that this seemingly innocent claim is a case of ‘bait and switch’. The problem, from the very beginning of “serious biographical work about Shakespeare”, was not that Shakspere’s life is “boring” (though it surely was and is), but that it is, in two words, incongruous and paradoxical. This is not a matter of debate. A serious argument must explain the problems and not sweep them under the rug when no one has the opportunity to object. Bate continued:

He made money out of his plays. He was shrewd enough, unlike other playwrights who merely got paid on a piecework basis, he was shrewd enough to become a shareholder with the actors and take a share of the box office profits, and it allowed him to buy a big house back home in Stratford.

How much “historical evidence”, “truth” and “fact”, is there in Bate’s statement? Not much. William Shakspere (assuming him to be the ‘shareholder’ recorded under the name ‘Shakespeare’), had obtained a minimal one-tenth share in the acting company. That much we will concede. But there is no evidence that he ever received any remuneration from that investment, or that he was “shrewd”, or that he was an active participant in the company in any capacity. As for being paid for writing plays, strangely, the name Shakespeare is conspicuously absent even from Henslowe’s Journals (as Alexander Waugh pointed out). And since there is no evidence that either Shakespeare or Shakspere ever received any payment for any play or poem, or for any performance, if we stick to the “facts” (as Bate seemingly promised to do), there is no way to identify the source of funds by which he was able to purchase a thirty-four-room house “back home in Stratford”. That is just one of the unexplained mysteries of Shakspere’s biography. Having invented numerous facts about Shakespeare’s career and character, Bate then slides once more into his all-inclusive ad hominem about anti-Stratfordian ‘snobbery’:

Now, in the 19th century, the romantic period, everyone wanted great authors to be glamorous. The most famous author of the age was Lord Byron. So they wanted Shakespeare to be a glamorous aristocrat like Lord Byron. Alas, though, he wasn’t. The true story of Shakespeare is a story about how you can come from the middle classes and with a grammar school education, no university education–Shakespeare was much mocked for not having a university education–you can become a great writer.

At risk of sounding like Professor Bate, the irony of a professor of English literature championing rustic populism never seems to penetrate the Stratfordian mind. However, saying (falsely!) that this is a “true story” is not an argument even if it comes from a knighted Oxford professor.

Marshalling the ‘Facts’ for Stratford

And now, a fourth of the way through his monologue, Bate ‘begins’:

Right, let’s begin with the facts. In the will of William Shakespeare, Shaksper, Shaxberd—people were very, very relaxed about spelling in those days—in the will of the man from Stratford he leaves mourning rings to his friends, John Hemmings, Henry Condell, and Richard Burbage, the leading actors of his acting company, the Lord Chamberlain’s, later the King’s Men.

Note, “with the facts”! Will come back to that. In the follow-on discussion, a man from the audience returns to the question about Shakspere’s bequest of rings to his theater colleagues. The man says:

I’d like to ask you a question about the will…Enoch Powell points to the will and he says that the names of Heminges and Condell that connect the will to the First Folio have been interpolated into the will.

Bate responds:

Scholars have examined Shakespeare’s will for a long long time, for more, a hundred years, for two hundred years. There are interleavings in the will, in particular the famous ‘second best bed’ is an interleaving. But, there is absolutely no evidence that the Hemmings, Condell, Burbage bequest is interleaved. It’s, it’s, I’m afraid Powell was a great man but he was simply wrong about that?

Waugh responds:

It’s not ‘interleaved’. It’s the wrong word. What he’s written is ‘interlineal’. It’s written between the lines and we don’t need to argue about that. It’s written between the lines. And when you write something between the lines you should endorse it, and there are no endorsements on these things. (1.11.03)

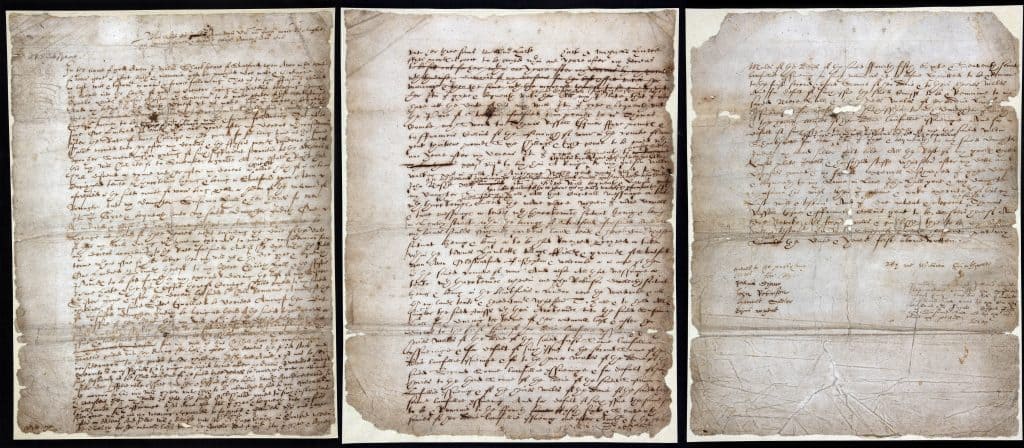

Bate is inadvertently correct when he says (demonstrating an ignorance of the terminology), the bequest in question was not “interleaved”. An ‘interleaving’ is an insertion of pages. On the substance of the question Waugh is correct, (and so was Powell). The bequest was an ‘interlineation’, written between the lines. As Waugh points out, legally, interlineations require a validating “endorsement” by the testator. These endorsements are lacking for all of the interlineations in Shakspere’s will. We won’t make a fuss over Bate’s erroneous terminology, but we do need to make a fuss over his claim that, “there is no evidence that the Hemmings, Condell, and Burbage bequest was interleaved”, by which we take him to mean ‘interlineated’. This is a very curious assertion! Looking at the Schoenbaum facsimile,[6] and the Chambers facsimile,[7] though the interlineations are a bit hard to see, they are visible as such. There are several websites where the will can be viewed. Here’s an image of the complete will:[8]

The interlineated bequest to Heminges, Burbage, and Condell, is written between the original lines 14 and 15 of page two (center above). It reads:

& to my ffellowes John Heminges, Richard Burbage & Henry Cundell xxvis viiid A peece to buy they Ringes.

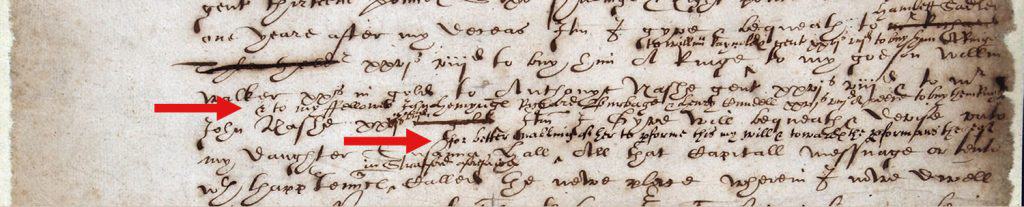

Here is an enlargement of that portion of page 2 (the top arrow points to the interlineation in question):

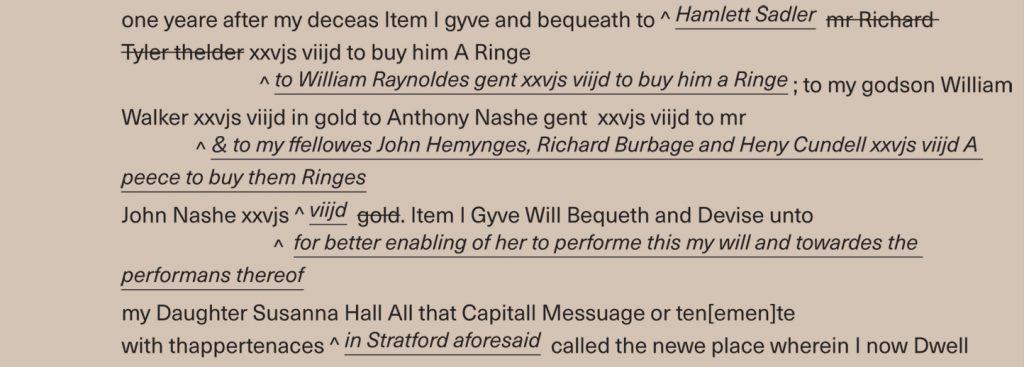

Edmund Chambers’ transcription of the will shows changes and interlineations underlined.[9]

Chambers shows the bequest as an interlineation. That the wording in question is an interlineation has never been in dispute. However, here again is Bate’s statement:

But, there is absolutely no evidence that the Heminges, Condell, Burbage bequest is interleaved.

We await Professor Bate’s explanation.

The Monument: Then and Now

In the following, as Bate continues, there are a number of simple ‘facts’ that we can agree to, with comment:

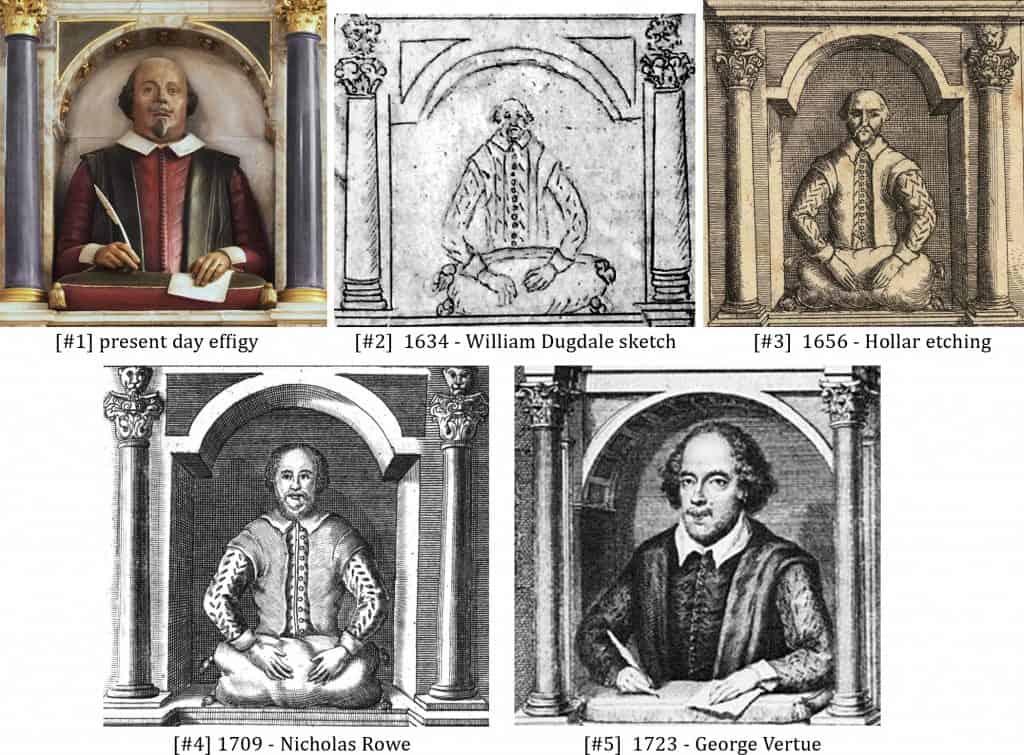

On his tomb he is described as a great writer, praised for his wit. He is said, on his funeral monument in Stratford church, to combine the wisdom of Socrates with the art of Virgil. That monument was transcribed within a year of his death. It’s alluded to in poems of praise. It’s copied by pilgrims going to Stratford. From the 1620s onward, people are going to Stratford saying this is the home of the great writer. His monument, of course, shows him holding a pen and paper.

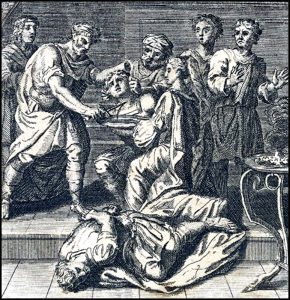

Yes, ‘Shakespeare is praised’, but, the question remains, is Shakespeare Shakspere? Since the monument is in the Holy Trinity Church of Stratford, the prima facie evidence suggests that the Shakespeare of the monument is William Shakspere. But, as Waugh points out, certain things about the monument are suspicious and a prudent investigator will not be compelled to accept ‘first appearances’, especially in the Elizabethan-Jacobean era. I’ll just speak to the “pen and paper” that Bate cites as important evidence.[10] Let’s have a comparison of the current monument with its earliest representations:

Image #1 shows the monument as it exists today. Image #2 is William Dugdale’s sketch drawn on site on or about 1634.[11] Image #3 is the subsequent etching by Hollar as published in 1656. Image #4 is van der Gucht’s engraving from Nicholas Rowe’s Works of Mr. William Shakespeare of 1709. And image #5 is George Vertue’s illustration from 1723-1725. In the three earliest versions Shakspere’s hands are holding a sack of wool or grain (identifiable by the shape and the four knots). Considering the sack and the position of the hands, a “pen and paper” would be an odd addition.

It’s too bad no one asked Bate about Dugdale. What would he have said? In his follow-on comments Bate directed the audience to the website Oxfraud.com. Let us follow Bate’s recommendation. At that website an essay by Tom Reedy provides the standard answer.[12] Reedy says Dugdale made ‘monumental errors’. He says, “Dugdale’s artistic accuracy is the crucial heart of the argument.” As anyone with a basic knowledge of sketching would know, Reedy is wrong! Reedy fundamentally misunderstands the purpose of sketching (and art[13]). I speak as an artist. But let us consult a dictionary. Here, from Dictionary.com, is the primary definition:

Sketch (noun): a simply or hastily executed drawing or painting, especially a preliminary one, giving the essential features without the details.

There are different approaches to sketching, subject to the purpose, but I think it must be agreed that this definition fits the purpose of Dugdale’s sketching. Many of the features in monuments Dugdale sketched would have been generic. Such oft-repeated features would not be salient or ‘essential details’. That Dugdale’s attention would have been focused mainly on distinctive or salient features is, I propose, axiomatic. Further demonstrating Reedy’s misunderstanding of sketching, he holds up examples of Dugdale’s ‘errors of perspective’. Viewing Dugdale’s sketches as an artist, it is obvious that Dugdale was sacrificing accuracy and perspective in order to make essential features visible that would not otherwise have been visible (such as figures hidden behind other figures). In one case cited by Reedy, Dugdale distorted the perspective in order to show that the figure was praying over a book (presumably a Bible), which, from a direct 90° angle looks like a block.

Dugdale was no Rembrandt. That was not his purpose. A person (a presumed author) holding a ‘pen and paper’ on a ‘cushion’ (or a sack) would have been highly unusual and therefore highly salient. Cushions commonly appear on monuments of that era as a platform for hands holding a book or to kneel upon. Reedy was not able to find another example of a figure holding a “pen and paper” with a cushion as a writing platform. If the original monument did have a ‘pen’ and ‘paper’, why did Dugdale overlook both? It has been elsewhere suggested that the pen had been stolen. That seems plausible. But the paper? Dugdale missed that as well? No doubt Dugdale did overlook salient details here and there, but, among the examples presented by Reedy there is not a single example of Dugdale overlooking a genuinely ‘essential detail’. With Dugdale’s sketch we are looking at genuine eye-witness testimony. It is graphic. It is right there in black and white. That is as ‘factual’ and definitive as a ‘historical fact’ can be. The missing “pen and paper” are a glaring problem! But it is the “pen and paper” that Bate relies upon as a key ‘factual and evidentiary’ argument. The professor does not comprehend that his claim to fact is based on fiction. Bate continues:

Other writers in his lifetime praised him, spoke about his writing techniques. Ben Jonson, fellow dramatist. Shakespeare acts in many of Jonson’s plays. We have the cast lists of half a dozen Jonson plays and Shakespeare is acting there.

What is Bate saying? Let us read carefully. He seems to be saying that (bold emphasis inserted) “Shakespeare is acting there” in six of Jonson’s plays? This is very odd! The name Shakespeare appears in, and is limited to, two cast lists in Jonson’s Folio of 1616. Those two plays are Every Man in his Humour and Sejanus.[14] Is that “many”? Is that “half a dozen”? I don’t want to be picky, but I think it is fair to ask whether Bate is lying, misinformed, or whether he is just sloppy when referring to ‘factual evidence’ (on a subject in which he is supposedly a world-class authority). The problem is systemic. Bate says:

Jonson, when he goes north to meet the writer Drummond, talks about Shakespeare’s writing techniques. He also does so in his private notebooks. Others too. Francis Beaumont, William Camden, John Davis of Hartford, Sir George Buck, Leonard Digges, Francis Meres, the Cambridge author of the Parnassus plays, they all talk about Shakespeare as a writer.

Another set of half-truths. What did those “other authors” say and what did they mean? It requires lengthy discussion which Bate didn’t provide and for which I lack the space here. Bate simply assumes the best for his man, and, if we are not snobs, we will accept his assumptions as ‘historical facts’.

Recycled Manuscripts and “Hand D”

Bate continues:

Now the anti-Stratfordians will say, where then are his manuscripts? Why don’t we have the manuscripts to prove the signatures that survive of William Shakespeare are the same? Unfortunately, no manuscripts of any of the 600 published plays by any of the authors from the period survive. Once a manuscript went to the printer, the printer either recycled it or threw it away.

It appears that Bate did not consult Grace Ioppolo’s, Dramatists and their Manuscripts (2006), where, on pages 6-7, she lists 127 original dramatic manuscripts, not counting those she did not examine in various libraries. But, let us ignore the facts (as Bate does) and take Bate’s claim as it is. What is it about finished performed plays that made them ‘disposable’? What is about unfinished unperformed plays that made them worth keeping? Bate, as usual, is not in command of the facts or logic. And, are we certain that those ‘unperformed plays’ were never performed? No. But the truly serious problems with Bate’s arguments are yet to come. He continues:

However, a tiny number of theater manuscripts survive because they were plays that weren’t performed. One of those was a collaborative play. Collaboration in theater, then as in television and film now, the art of writing was collaborative art. Collaboration was the norm.

For this alleged “norm” the historical evidence, as usual, is missing. The First Folio contains 36 of Shakespeare’s plays. In the First Folio, there’s no mention of shared authorship. The First Folio gives Shakespeare full credit for all of them. Period! There is no clear ‘historical evidence’ for Shakespeare’s ‘collaboration’. None! Bate continues, and now he runs into serious trouble:

Shakespeare contributed a scene to a collaborative play about the life of Sir Thomas More that was banned because it was too politically sensitive. And handwriting experts have looked at the hand in that manuscript, and I’ve held [it] in the British Library, and found six particular features of handwriting which they then compared with Shakespeare’s signatures and with the handwriting of 250 other writers from the period and there are six features that only match Shakespeare’s.

The idea that you can positively ID an author of a few handwritten lines of a play by means of comparison to six signatures is preposterous. That should be the end of it. But no. Add to that the problem that no two of those signatures are the same. That should be the final blow to this absurd discussion. But the absurdity goes on and on. Of the “six particular features” Bate referred to, the one he submits into evidence is an ‘a’ written like a ‘u’ which allegedly corresponds to an ‘a’ in one of the signatures and Hand D. Grasping at the similarity of that one letter in that one signature, Bate ignores the countless dissimilarities in other letters and other signatures. As paleographic evidence goes, this, in a court of law, would testify to the gross incompetence of the expert witness and the lawyers who enlisted his testimony. Jonathan Bate would be well-served to read Diana Price’s essay, ‘Hand D and Shakespeare’s Literary Paper Trail’.[15] Further, as powerfully argued by Robert Detobel,[16] the ‘signatures of Shakspere’ are very likely not signatures at all, but entries made by a clerk on behalf of Shakspere, a common practice for persons who were illiterate. I must say that, having studied the evidence and the competing arguments, Bate’s reliance on ‘Hand D’ as a ‘factual argument’, boggles my mind.

He continues:

Letters. People say, why don’t we have Shakespeare’s letters. Well, we do have a couple of Shakespeare’s letters. They were appended to his poems, the poems which made his name: Venus and Adonis and The Rape of Lucrece, and they are rather servile. They’re saying please give me patronage my Lord Southampton. The idea that an earl like Oxford, one of the great earls of the land, would have written these servile flattering letters to a mere junior aristocrat, a twenty-year-old whippersnapper like Southampton is inconceivable.

This too would require a long discussion. I’ll simply mention my surprise that Bate, a professor of English literature, would casually toss out the distinction between a ‘dedication’ (an ‘epistle dedicatory’ they called it), clearly written for publication, and an actual ‘letter’ sent from one person to another. Bate continues:

The theory about Oxford . . . or some other aristocrat having to write under a pseudonym because they were worried about being associated with the theater is frankly bizarre. The earl of Oxford was patron and sponsor of a theater company, Oxford’s Men, they toured in the provinces in the 1580s and 90s. If Oxford was proud of his involvement with the theater why didn’t he write the plays for Oxford’s men? If he was ashamed, then why did he have an acting company?

Bate neatly ignores the very core of the Oxfordian argument, i.e., that Oxford was going to great trouble to conceal his authorship. Bate isn’t making a factual argument. He is, once again, expressing his opinion as if it is a factual argument. He continues:

We hear that Shakespeare’s father was illiterate. It’s funny then that there’s a will in which someone leaves him some books, a strange thing to leave to an illiterate man.

As, Schoenbaum says, “but, no signature of John [Shakspere] survives, and the natural assumption is that, having been reared in a country village without a school, he never learned to write.”[17] John signed with a mark. It’s “funny”, but that’s the fact of the matter. As for someone leaving him a book in a will, could it be that this was because books were among the most valuable kinds of movable property in those days?

Shakespeare the Aristocrat?

Bate continues:

Now, one of Alexander’s big arguments is that the person who wrote the plays must have gone to Italy because there’s lots of detail about Italy in the plays. Those would be plays where two of them are set in Venice and there’s no single mention of a canal. [Slight audience laughter] There are certain details about Italy that seem to be authentic, but equally Ben Jonson never went to Italy, and yet in Volpone he knows the location of the portico to the Procurata. John Webster never went to Italy, yet in the Duchess of Milan [Bate means “Malfi”] he knows the location of a lane behind Saint Mark’s Church. You can pick up knowledge from books and conversations. We might just as well say, how did Shakespeare know about the details of the platform at Elsinore in Hamlet? The answer would be that three of his fellow actors in the acting company, Bryan, Pope and Kemp, went to Elsinore and told him about it. The earl of Oxford never went to Elsinore.

Regarding the ‘canals in Venice’ that Shakespeare failed to mention, what is Bate’s point? Shakespeare didn’t know about the canals? That’s a strange argument. If, as Bate claims, Shakspere gathered all sorts of detailed information about Italy from ‘books’ and ‘conversations with persons acquainted with Italy’, did he fail to learn about the canals, the thing for which Venice is most famous? Or could it be that the real Shakespeare, who had been to Venice, was confident that everyone (even the average Londoner), knew about the canals and, therefore, didn’t bother to gratuitously mention them?

Regarding Elsinore, we could employ the Stratfordian method of argument and say that, since there is no proof that Oxford never went to Elsinore (Kronberg Castle in the town of Helsingør), we must assume that he did.[18] What I can say is, I have been to Elsinore and it doesn’t look much like what I’ve seen in the plays or movies of Hamlet, for whatever that’s worth. As for Italy, we don’t have time here. See Richard Roe’s, The Shakespeare Guide to Italy, (2011).[19] Bate continues:

How could this humble middle-class boy from the grammar school have known so much about aristocratic households? According to John Dryden, the 17th century writer much closer to aristocratic households at the time, than we are, he writes that Shakespeare understood very little of the conversation of gentlemen.

Dryden is a marginally credible witness. He undoubtedly had much contact with “gentlemen”, but he wasn’t an aristocrat. He was a brilliant prolific writer, authoring more than two dozen dramatic works, but he was not an enthusiastic dramatist, preferring non-dramatic writing. To coin a phrase, Dryden was no Shakespeare, by which I mean to suggest that Dryden did not appreciate Shakespeare’s ‘dramatic touch’ with aristocratic or ‘gentlemanly’ conversations. “Funny”, but Shakespeare’s depictions of aristocratic conversations were good enough to impress Queen Elizabeth and King James, or so we are told.[20] Bate continues:

Shakespeare was actually pretty useless at representing what aristocratic households, with hundreds of retainers were really like. Just have a look at Romeo and Juliet where the character of Capulet, leading aristocrat, his daughter’s about to be married to Paris the kinsman to the prince, he’s down in the kitchen speaking to the staff. No, that sort of thing didn’t happen. Shakespeare didn’t know about Italy. He didn’t know about aristocratic households.

If Oxford were here I think he’d be quite amused. I can only guess that Professor Bate has not been to Verona and hasn’t visited the House of Capulet (Casa de Giulietta). The play isn’t historical, so we can’t expect the house in the play to match one-for-one the actual house. But it’s worth taking a look.

The house, we are told, is more or less as it stood in the 13th century in terms of location and size. The cute little balcony was added in the 20th century to please the tourists, and the whole side of the building was nicely redone so that it looks nothing like it did in the beginning of the 20th century. It looked like a cheap tenement. The house, as it stands today, was turned into (converted to) a tourist attraction. It is not ‘historical’ in any meaningful sense. It sits in the central part of the historic old town, wedged in between other houses (typical for historical Italian cities), barely a stone’s throw from the famous Arena di Verona. It’s not even close to being a palace or mansion. It’s a house, and it’s not very big and not very impressive. For the house itself, common sense says that a handful of servants would be plenty.

Perhaps Capulet owned land outside of the city walls, or other houses, where he employed servants, but in that house, the “hundreds of retainers” imagined by Bate, would have been packed in like sardines all the way up to the rafters. Capulet wasn’t a titled nobleman. He was a titleless member of the early bourgeois class of Italy. Bate’s understanding of conditions in England is no better. The living standards for English nobleman varied considerably. Bate’s claim that an English earl would ipso facto have had “hundreds of retainers” continually employed in their households or stables, or whatever, is extraordinarily naïve. Let us consider an inconvenient historical fact. In 1583, in a letter to the queen, William Cecil reported his concern that Oxford and his wife were living in poverty with only three servants.[21] Three![22] Not three hundred! Did Oxford speak to them? I boldly suggest that that ‘did happen’.

Shakespeare the Country Boy?

Bate continues:

What did he [Shakspere-Shakespeare] know about? He knew about wool trading and leather manufacture. His father was a glovemaker. The plays refer to calfskin, sheepskin, lambskin, foxskin, dogskin, deerskin, kidskin, neat’s leather, and leather for a bridle.

So, knowing about leather and wool-trading makes Shakespeare the son of tradesman, but knowing about law, falconry, seamanship, botany, birds, etc. makes him a book’s man. So goes the argument. Bate continues:

Shakespeare was above all a countryman.

Who wasn’t? In the 16th century England was 99.999% “country”! The only big city was London and London wasn’t that big. Walk fifteen minutes from St. Paul’s Church in the center of town and you’d be in the “country”. Of course we don’t know, since no one bothered to document the matter, but it is rather unlikely that the average Londoner spoke ‘the king’s English’. Shall we suppose that, when earls weren’t kneeling in the presence chamber they holed up in their studies conscientiously refusing to speak to their servants?

There was no TV or radio. There were no newspapers or magazines. Life could be pretty boring in those cold damp castles, nearly all of which were ‘in the country’. When the weather was good, understandably, earls often went poking around their dominions, ‘in the country’. They went hunting ‘in the country’. Ladies went walking and riding ‘in the country’. Queen Elizabeth went riding and hunting ‘in the country’! Ben Jonson walked to Scotland through the ‘country’. ‘Shall I compare thee to a summer’s day?’ A summer’s day was something to savor, even by lords and ladies, in their gardens, or in ‘the country’. Bate continues:

Look at the countryman in The Winter’s Tale speaking about tods equaling pounds and shillings for wool. This is countryman’s language. Six hundred plays from the period survive. The only ones that mention Warwickshire and Gloucestershire are those by Shakespeare.

What are ‘tods’?

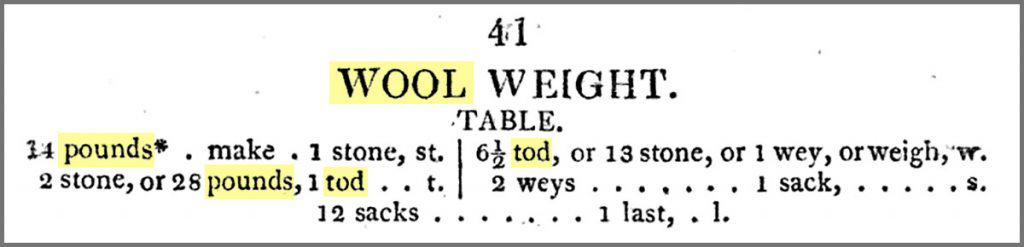

‘Tods’ were the standard unit of measure for wool, from A System of Practical Arithmetic by Rev J. Joyce, 1812.[23]

‘Tods’ were the standard unit of measure for wool. Is this obscure terminology that would only have been understood by a “countryman”? Hardly. For the purpose of taxation, the state controlled the trading of many ‘commodities’ such as tin and beer and wool. The crown would typically grant a preferment to a nobleman who was then authorized to control the trade of a particular commodity and levy a tax or duty, which, as a rule, that nobleman was allowed to retain for his official income. A nobleman concerned with the wool trade would have known what ‘tods’ were. Wool trading was one of the preferments requested by (but not granted to), Edward de Vere, the Earl of Oxford.

However, even if we assume that ‘tods’ was the “language” of a ‘countryman’, does that make the author a ‘countryman’, or does that make him a good writer? As for ‘Warwickshire and Gloucestershire’, that’s very interesting, and I’ll come back to that. And Bate says:

There’s a little problem for the argument about earl of Oxford writing Shakespeare. He died in 1604. A large number of Shakespeare’s plays were written thereafter.

There would be a “problem”, except that there is not a scrap of factual proof that any Shakespeare play was written after 1604. There’s not an iota of proof by which to date any of the 37 canonical plays, not so much as a smidgit, or make that a smidgen, of factual evidence, as Richard Whalen has forcefully argued.[24] Nevertheless, the so-called ‘standard chronology’ has become the centerpiece of the anti-Oxfordian argument. Waugh gave the obvious and very adequate answer. Revisions. Why should Oxford’s plays not have been updated after his death? Why is it that Stratfordians love the idea of collaboration but are allergic to the idea of revisions? They insist on collaboration because a dead man can’t collaborate. Once more Bate’s argument is neither historically factual nor does it hold up to common sense, as with this curious claim:

Collaboration in theater, then as in television and film now, the art of writing was collaborative art. Collaboration was the norm.

The “norm”? In the theater, there is a kind of ‘collaboration’ that takes place when a play goes into production on the stage. This may involve the director, the producer, and the actors, resulting in adjustments to the playwright’s text in the play as performed. Whether such adjustments are reflected in a published text is another matter. More to the point, among modern dramatists, collaboration seems to have been much more incidental than “the norm”. I say “seems”. If Bate has evidence to support his claim, we ask that he kindly share it with us.

England or Britain? Elizabethan or Jacobean?

And now he wades into the quicksand of style and stylometrics:

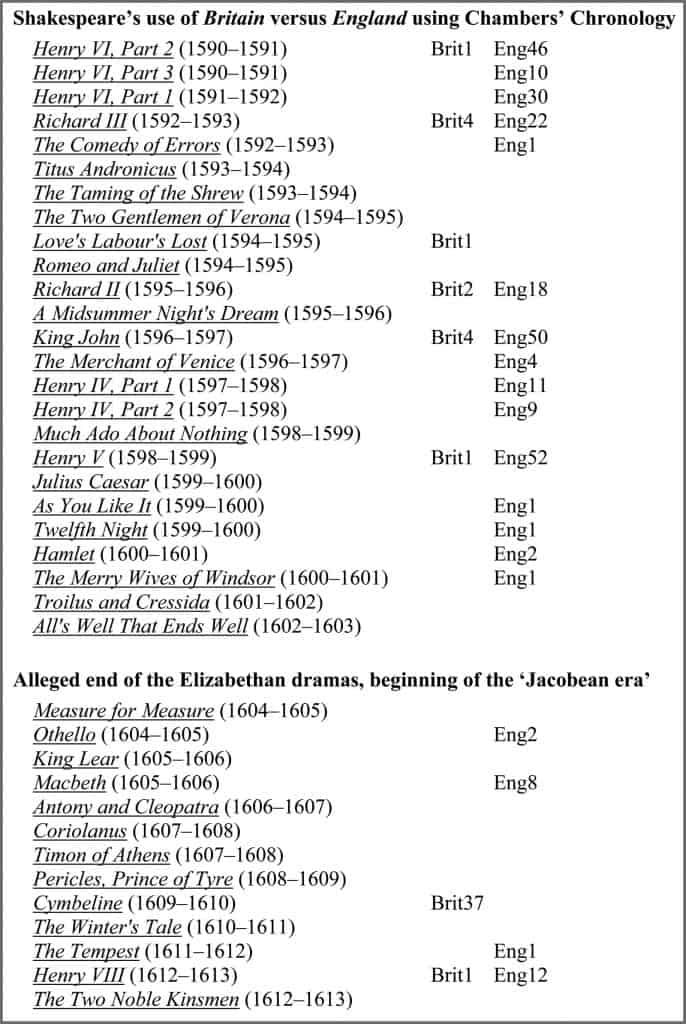

In the plays that Shakespeare wrote in the reign of Queen Elizabeth he always talks about England because she was Queen of England. In the plays he wrote for King James after James came to the throne in 1603 he wrote about Britain because King James wanted to unite England and Scotland into Britain. Macbeth, King Lear, and Cymbeline are specifically linked to the Jacobean project.

I’ll be polite and call it nonsense. Let’s follow the ‘standard dating’ according to E.K. Chambers and check the facts which, evidently, and amazingly, Bate didn’t bother to do. If we had time we’d consider the context and meaning. I’m going to keep it simple, and that should be more than adequate. I’ve annotated the plays that make reference to ‘Britain’ (Brit) and ‘England’ (Eng) including possessives. I show the frequency to the right:

Shakespeare’s use of Britain versus England using Chambers’ Chronology[25]

Here again is Bate’s statement:

In the plays that Shakespeare wrote in the reign of Queen Elizabeth he always talks about England because she was Queen of England. In the plays he wrote for King James after James came to the throne in 1603 he wrote about Britain because King James wanted to unite England and Scotland into Britain. Macbeth, King Lear, and Cymbeline are specifically linked to the Jacobean project.

I assume the list speaks for itself but I’ll break it down anyway. As one would expect, the large frequency of the word ‘England’ is in the history plays, which everyone agrees are Elizabethan. However, counter to what Bate suggests, ‘Britain’ does show up in five of those. Considering Bate’s statement it is remarkable that ‘Britain’ shows up in 6 Elizabethan plays and only 2 Jacobean plays, and that 11 of 13 so-called Jacobean plays, have no mention of ‘Britain’ whatsoever. Looking at this a few more ways, 60% of the plays where ‘Britain’ is used are Elizabethan plays.

For the occurrence of ‘Britain’, the play Cymbeline is the huge exception. Why is ‘Britain’ mentioned 37 times in Cymbeline? To please King James? The play’s a ‘romance’, a fantasy, with a ridiculous story-line. It’s hardly a glorification of England or ‘Britain’. James would have been impressed? I don’t think there is any basis on which to proclaim King James an expert on drama or poetry. But if Shakspere’s idea was to suck up to King James by mentioning “Britain” over and over, why Cymbeline? And why just Cymbeline? Why not in Macbeth? Why not King Lear? Why not Henry VIII? On the other hand, if Shakespeare, or some ‘collaborator’, did go out of his way to ‘Britainize’ Cymbeline to please King James, there’s nothing (apart from speculative dating arguments), to say that that version wasn’t a revision of an older Cymbeline.

I have to emphasize that, by ignoring the subject-matter and historical context of the plays (as Bate does), counting the occurrences of these two words (‘Britain’ versus ‘England’) is a perfectly silly exercise. However, if we do assign significance to these occurrences, unless we somehow assign special importance to Cymbeline, and can definitively date it, the numbers and the dating absolutely refute Bate’s argument.

Looking back once more at Bate’s statement, it is categorically false! How can he not know that? Considering the formulation of his statement, he is especially misleading with regard to Macbeth and Lear where there is not a single mention of ‘Britain’ in either play. To be absolutely accurate, there is, in Lear, one reference to “a British man”. In Macbeth (considered by Stratfordians to be the Jacobean play) there is nothing close to a reference to ‘Britain’. Macbeth falls in the indefinite medieval time-frame, about 1,000 A.D. If the usage of ‘Britain’ versus ‘England’ is the measure of a Jacobean play, Henry VIII, with 12 occurrences of England, and only one occurrence of ‘Britain’, must be an Elizabethan play (I suggest a dating of 1581-4). When you make an important argument, it goes without saying that you present your strongest evidence. This is the strongest evidence Bate could come up with? So much for the “Jacobean project”. Bate continues:

Similarly, in 1608 Shakespeare’s acting company acquired an indoor playhouse so that, instead of acting outside in natural daylight they had to have candles. So in his late plays he starts introducing act divisions, the five-act structure so there was a break so the candles can be replaced. Oh, that Earl of Oxford was a clever chap. He realized that four years after his death there would be an indoor theater. So he must have written some plays like The Winter’s Tale and The Tempest with act breaks just preparing for it.

Alexander Waugh points out that it is an absurd argument, saying that, for example, they could simply have used longer candles (and probably did), and that the five-act structure was already in place during Elizabeth’s reign and dates back somewhat further, to the ancients of Greece.

Collaborating with John Fletcher

Bate says:

And then, most interestingly of all, at the end of Shakespeare’s career he’s got to decide who’s going to take over as the leading playwright of the acting company, and he chooses a young dramatist called John Fletcher who came on to the scene in 1607.

I suspect that many in that audience were surprised at the news (we could legitimately call it “fake news”) that Shakespeare ‘chose his replacement’. There is not a scrap of factual evidence suggesting that Shakspere had any involvement in ‘selecting his replacement’ or that he ever met John Fletcher. Where is the ‘historical evidence’ Bate promised? Instead he continually conjures up fantasies and expects us to accept them as ‘historical fact’. He does so with a professorial face. His confidence in these tales of collaboration arise from ‘stylistic’ and ‘stylometric studies’, as he goes on to explain:

In Shakespeare’s last three plays, The Two Noble Kinsmen, Henry the 8th, and the partially lost play Cardenio, are co-written with Fletcher. For 150 years scholars have been able to identify different linguistic fingerprints of Shakespeare and Fletcher. Shakespeare says ‘you’. Fletcher says ‘ye’. Shakespeare says ‘them’. Fletcher abbreviates to em, apostrophe e m [’em]. Feminine endings and unstressed syllable at the end of the line. Very different patterns in Shakespeare and Fletcher. So, we know as Shakespeare and Fletcher sat down to write Henry the 8th and The Two Noble Kinsmen together, which scenes were Shakespeare and which scenes were Fletcher. I’m struggling to imagine how Oxford did that from beyond the grave, let alone how he collaborated with Fletcher in the play of Cardenio which was based on Don Quixote, 1605, after Oxford’s death, and indeed has allusions to the 1612 English translation.

No, we do not “know” that Shakespeare and Fletcher or Fletcher and Shakspere ever “sat down to write” anything. There is zero evidence of that. But let’s focus on the specific ‘evidence’ Bate offers up. Here again is Bate’s statement:

Shakespeare says ‘you’. Fletcher says ‘ye’. Shakespeare says ‘them’. Fletcher abbreviates to em, apostrophe em [’em].

I think the natural inference from Bate’s statement is that Shakespeare always used ‘you’ and never used ‘ye’. If this distinction of usage is not clear, how could the occurrences of ‘you’ versus ‘ye’ lead to a meaningful sorting out of who wrote what? I mean, if Shakespeare also used ‘ye’ and ‘em’, how should we know who the author was in any occurrence of ‘you’ and ‘ye’ and ‘them’ and ‘em’? Surely Bate would not build an important argument on a non-existent distinction? Or? Alas. The fact of the matter is that Shakespeare does say ‘ye’ and Shakespeare does use the abbreviation ‘em’, and the evidence of that, as ye shall see, is beyond question. Pulling out my Harvard Concordance to Shakespeare, Shakespeare says ‘ye’, not just once or twice, but 346 times. In fact, he says ‘ye’ in all of his plays and in Lucrece and his Sonnets. As for ‘em’ in place of ‘them’, he uses the abbreviation ‘em’ in 22 plays.

So, if you accept the theory of shared authorship of Two Noble Kinsmen (TNK), by collaboration or revision, and if you are looking at the occurrences of ‘em’ and ‘ye’ to determine which part was Shakespeare’s or Fletcher’s, how do you do that? How do you distinguish Shakespeare’s ‘ye’ and ‘em’ from Fletcher’s ‘ye’ and ‘em’? Is there something in the syntax or context that allows us to make those distinctions? Somehow the computer ‘knows’ and that’s how we “know” that Shakespeare and Fletcher collaborated on three plays. If you believe it. I don’t! I don’t think Bate has any idea how this distinction would be made. I don’t think he’s spent any time thinking about it. As to revisions I’m open-minded and will suggest that, for TNK, Fletcher co-oped a much earlier play by Oxford called Palomon and Arcite.

Shakespeare’s and Peele’s ‘Fingerprints’ in Titus Andronicus

My own speculation aside, we come now to Shakespeare’s alleged collaboration with George Peele, where, once again, according to Bate, “we know”. Bate says:

But, thanks to those advancements in stylometric study we now know things we didn’t know before. For instance, we know when Shakespeare, early in his career wrote Titus Andronicus he collaborated with George Peele. And we know that because Peele used ‘brethren’ as the plural of brothers and Shakespeare used ‘brothers’, and we know from that: Peele wrote the first act and Shakespeare wrote the rest. So, it’s something to be celebrated that we have these debates because eventually the truth will out! [Sits down. Applause.]

First of all, it must be observed that Bate’s firm opinion has changed. In the introduction to Titus Andronicus[26] which Bate edited in 1995, he says, “I believe that the play is wholly by Shakespeare”. Now, in 2017, he attributes the first act to George Peele, saying, “And we know that because Peele used brethren as the plural of brothers and Shakespeare used brothers”. Interesting!

Reading Bate’s statement carefully, I infer that Titus Andronicus was not “wholly by Shakespeare”. Permit me to slightly restate Bate’s argument. We ‘know that Shakespeare collaborated with Peele because Peele had a preference for ‘brethren’ and Shakespeare had a preference for ‘brothers’.’ In other words, it is a matter of authorial preference and these authors were presumably consistent in these preferences. That, as I understand it, is Bate’s argument which he borrowed from the experts in stylometrics, ‘who use computers’, and this, again, is presumably some of the strongest evidence for the argument for collaboration, which makes the ‘facts’ of the matter absolutely astounding.

Evidently those sophisticated computer experts didn’t have a dictionary (and neither did Bate), and evidently, they aren’t much with actual words, for those computer experts (and Bate) failed to consider that the primary meaning of ‘brothers’ is not the same as the primary meaning of ‘brethren’. The primary meaning for ‘brothers’ is male siblings. The primary meaning of ‘brethren’ is ‘a group’, as in a clan or nation, etc. If you don’t believe me, please consult a dictionary, any dictionary. ‘Brethren’ is seldom used to mean siblings but, to be clear, it can be used that way. The examples Bate is using for his very important argument are from Titus Andronicus where ‘brethren’ is used 9 times (counting ‘bretheren’ and ‘brethren’s’). Eight of those in are in Act 1. In this same play ‘brothers’ is used 8 times including Act 1.

Now, here’s the amazing thing. In this play, in all cases where ‘brethren’ and ‘brothers’ (and ‘brother’) are used, the usage, without fail, 100% of the time, follows the primary dictionary meaning. Let’s have some examples of each. Here are the first three instances in the play where ‘brethren’ appears (bold emphasis added):

TAMORA

Stay, Roman brethren! Gracious conqueror,

Victorious Titus, rue the tears I shed,

A mother’s tears in passion for her son:

And if thy sons were ever dear to thee,

O, think my son to be as dear to me!

Sufficeth not that we are brought to Rome,

To beautify thy triumphs and return,

Captive to thee and to thy Roman yoke,

But must my sons be slaughter’d in the streets,

For valiant doings in their country’s cause?

O, if to fight for king and commonweal

Were piety in thine, it is in these.

Andronicus, stain not thy tomb with blood:

Wilt thou draw near the nature of the gods?

Draw near them then in being merciful:

Sweet mercy is nobility’s true badge:

Thrice noble Titus, spare my first-born son.

TITUS ANDRONICUS

Patient yourself, madam, and pardon me.

These are their brethren, whom you Goths beheld

Alive and dead, and for their brethren slain

Religiously they ask a sacrifice:

To this your son is mark’d, and die he must,

To appease their groaning shadows that are gone.

These three usages of ‘brethren’ are all references to a ‘group’, not to siblings. And, by the way, contrary to what Bate seems to have implied, the words ‘brothers’ and ‘brother’ do occur in Act 1. So, as an example of ‘brothers/brother’, let’s see those examples:

MARCUS

Long live Lord Titus, my beloved brother,

Gracious triumpher in the eyes of Rome!

Marcus Andronicus is the brother (sibling) of Titus Andronicus. And the example of ‘brothers’:

MUTIUS

Brothers, help to convey her hence away,

And with my sword I’ll keep this door safe.

Exeunt LUCIUS, QUINTUS, and MARTIUS

Mutius, Lucius, Quintus and Martius are the sons of Titus Andronicus, i.e., male siblings. All of this is in Act 1, which Bate attributes to Peele. If Peele wrote Act 1 using his preference for ‘brethren’, why did he switch to Brother and Brothers? It’s an absurd question if one pays attention to the primary meaning of the words ‘brethren’ versus ‘brothers’. The usage of these words in Titus Andronicus is not a matter of authorial habit or preference. It is, without exception, a matter of the primary meaning of these words. It’s that simple!

But that’s not the only problem with Bate’s argument. He claims that Shakespeare doesn’t use ‘brethren’, and the fact of the matter is that he does. Shakespeare uses ‘brethren’ 11 times in a total of 8 plays besides Titus Andronicus. In all cases his usage follows the primary meaning.

I could be cute and say that Bate’s claims about Peele’s collaboration are more ‘fake news’, but, to be precise, they are ‘false news’, ‘completely false news’. The fact of the matter is that Bate’s argument isn’t just a little wrong, it is utterly false and utterly embarrassing. Now, who’s to blame? The computers? The computer scientist? The statistician? Or is it the ‘eminent Shakespeare scholar’ who trusted them, who failed to check the supposed ‘facts’ which are very easily checked without a computer?

And why didn’t Bate check? How could he not check? It’s not hard to do. All you need is a concordance and a dictionary. I expect a professor of English would not even need a dictionary. Indeed, come to think of it, why would Bate need to check at all? How could he not simply know? Let us recall this from the moderator’s introduction:

And he is, his influence is such that his Arden edition in 1995 of Titus Andronicus totally revised our feelings about the play.

Bate is an authority on Titus Andronicus! He must have read it countless times. How could an expert like Bate get hoodwinked by people with ‘computers’ about something as silly as ‘brethren’ versus ‘brothers’? What does this tell us about the competence of the hoodwinkee who happens to be a professor of English literature? But the problem goes further. In his introduction to Titus Andronicus, Bate makes brief mention of the work and opinions of J.M. Robertson, Dover Wilson, J.C. Maxwell, MacDonald P. Jackson, and Gary Taylor. Bate’s opinion, as of 1995, runs so:

The problem with all the arguments based on verbal parallels is that imitation is always as likely as authorship. . . There is no copyright on coinages. . .What follows from this need not be that Peele wrote the first act of Titus, but rather that Shakespeare read the poem [Peele’s, The Honour of the Garter] and snapped up the word [‘Palliament’] . . .[27]

Shakespeare, according to Bate, engaged in “linguistic filching”. That the “filching” may have been from Shakespeare, Bate does not consider. At any rate, in 1995, Bate concludes:

The play’s structural unity suggests a single authorial hand . . . All language-users have their characteristic but subliminal pattern of functional words – connectives, articles, prepositions and pronouns – which constitute a linguistic fingerprint as opposed to poetic plumage. Computer analysis of these suggests what literary judgement confirms: that the whole of Titus is by a single hand and that at this level its linguistic habits are very different from Peele’s. According to Andrew Q. Morton, who undertook the analysis, the statistical probability of Peele’s involvement is less than one in ten million (Metz, ‘Stylometric’, 155).[28]

That, in the 1995 introduction to Titus Andronicus, is Bate’s very clear final word on the subject. Twenty-two years later:

But, thanks to those advancements in stylometric study we now know things we didn’t know before. For instance, we know when Shakespeare, early in his career wrote Titus Andronicus he collaborated with George Peele.

As to “advancements” that led to Bate’s flip-flop on the question of Peele’s authorship of Act 1 of Titus, I can only infer from what he tells us about brethren versus brothers. I do not fault Bate for changing his mind, but I do marvel at the reason for his conversion. I am compelled to the impression that, though Professor Bate has great confidence in stylistic and stylometric evidence, he evidently knows very little about these methodologies and the ‘evidence’ they produce. The fact that Bate did not bother to check the evidence he presented suggests to me that he finds it technically intimidating or that he is a sloppy scholar, or both. Nor does he appear to understand that his examples are not dependent upon ‘advanced computer analytics’. The examples submitted into evidence by Bate are nothing but basic word-usage comparisons, not stylometrics. However, the “stylometric evidence” (as Bate refers to it) is so important that Bate returns to it in his summation at the end of the debate. He says:

I’m not going to take three minutes. I’m going to say something very, very, very simple, which is, that, in the end everybody has a distinctive linguistic register, and as I said before, one of the things the authorship debate has been very good at is really getting people working in a much more sophisticated way on the authorship of the plays in the period. This used to be done impressionistically. The first person who thought that the Earl of Oxford wrote the works of Shakespeare was a delightful Edwardian schoolmaster called J. Thomas Looney [noticeable reaction from the audience] who was convinced . . . please don’t interrupt [to the audience]. It’s extremely rude . . . who was convinced that Delia Bacon was wrong but still convinced that Shakespeare didn’t write Shakespeare, so he started reading plays and poems by other people from the time to try to find who was Shakespeare, and he alighted on the poems of the Earl of Oxford, and in an impressionistic way thought he saw similarities with Shakespeare.

Now, about this notion of ‘linguistic registers’ or ‘linguistic fingerprints’. The term ‘registers’ is too vague to deal with, but ‘fingerprints’ is something very specific. Bate’s use of this analogy seems sensible, unless you actually think about it. Your fingerprint is what it is. In forensics, on a computer screen, a fingerprint is a set of graphic data points on a grid. One fingerprint is of one of ten possible images (assuming a suspect has a full set of fingers and thumbs), and those do not change. You don’t keep growing fingers. Short of scarring, you can’t vary your fingerprint, consciously or subconsciously, and you can’t keep adding to it with millions of new bits of data, as you can with your writings. Nowhere is a word, sentence, paragraph, page, chapter, or book analogous to a fingerprint. What if we were to take an average of one person’s ten fingerprints and use that for comparison to a fingerprint in evidence? It’s absurd. William Ray notes that, “Twain was wildly enthusiastic about fingerprints as identity finders. He never transposed their utility into any other field. Bate has made the error of borrowing a physical fact, reconstituting it into metaphor, and claiming the erroneous metaphor as equivalent to fact.”[29] Bate’s use of the ‘fingerprint’ analogy is another example of sloppy logic.

Putting aside the false analogy, the problem of stylometrics is in the millions of bits of data within a huge data aggregate (written text) that is infinitely variable, and for which there is, again, no factually validated starting point or ending point and no confirmed portion of text. In my opinion Bate does not comprehend any of this, nor does he appear to care about exactitude or semantic fidelity. In his closing monologue, he says:

Now, what has happened a hundred years on is that the entire corpus of poetic and dramatic literature of the age of Shakespeare has been put on to databases so that we can now work out authorship in a much much more sophisticated, more nuanced way. Almost scene by scene we can see how playwrights are collaborating with each other. Everybody has their own linguistic fingerprint. And that, seems to me, to be an enormously valuable tool.

An “enormously valuable tool”? How so? If the problems of complexity could be overcome and stylometrics could be shown to work it might show us something, but would it actually have “value”? If we could perfectly divide Titus Andronicus into parts written by Shakespeare, George Peele, Robert Green, Thomas Kyd, Thomas Lodge, and perhaps Christopher Marlowe (as suggested by John Robertson back in 1906), what “enormous value” would that have? Outside of a tiny clique of academics, who would care? Following that train of minutia-bound thought, we end up with such a hodge-podge of collaboration that we cease to care about attribution all together. Stratfordians would celebrate. As William Ray points out, “politically speaking . . . the collaboration fad makes it at least ‘scientifically’ plausible to head off the historical authorship debate and temporarily convert it into a murky creative composite, ergo no Oxford threat and a way to keep publishing Shakespeareiana.”[30]

Why Is There no Stratford in Shakespeare?

Bate continues:

But there is still work to be done. I mean there are plays around the fringe of the canon that we don’t know to what extent they have a little bit of Shakespeare as well as someone else. . . So, I just want to leave you with, to remind you that, of the six hundred surviving plays from the period, the only ones to mention the counties of Warwickshire and Gloucestershire; of course Stratford is on the border of Gloucestershire, and if you read the scene in Justice Shallow’s orchard you have to know that’s written by a Cotswold man. . . . So, as much as I love the debate, I have no doubt that William of Stratford was the man.

Constrained as he was by the allotted time, Alexander Waugh was able to address only a few of Bate’s bogus arguments. He briefly rebutted Bate’s ‘Cotswold man’ argument. But, since Bate chose to ‘remind’ us in his summation about the importance of the “counties of Warwickshire and Gloucestershire”, it will be profitable to give those “counties” additional attention.