PBS, “Shakespeare Uncovered”: reviewed by Norwood (part 2)

Professor James Norwood explains how the PBS series Shakespeare Uncovered inadvertently reveals the inadequacies of the Stratfordian attribution of Shakespeare’s plays. In this second part of his review, Norwood examines episodes on The Taming of the Shrew and Othello. In part 1, he reviews episodes on A Midsummer Night’s Dream and King Lear. In part 3, he reviews episodes on Antony and Cleopatra and Romeo and Juliet. See Shakespeare Uncovered for more information.

by James Norwood

February 8, 2015 — When I was a graduate student at Berkeley, my first course was an intensive, three-part seminar in Shakespeare. At the end of the academic year, the professor informed us that he would be taking a sabbatical and that his next research project would be simply to walk from Stratford-upon-Avon to London, carefully recording his impressions along the route that the author had trod so many times during his career as a playwright and man of the theater. The professor believed that if he could retrace the footsteps of the author, then he would surely discover some of the clues to unlocking Shakespeare’s creative genius in the literary works. What was the result of this endeavor? Nothing.

The professor subsequently abandoned his Shakespeare project and spent the remainder of his life in studies of the American playwright Eugene O’Neill, becoming the foremost O’Neill scholar of the twentieth century. Upon his retirement, he became the steward of the National Historic Site of the Tao House in Danville, California, where O’Neill had written his masterpiece, Long Day’s Journey Into Night. But the professor was never able to navigate his way to a similar base of experiential evidence for the life of William Shakespeare. The problem was that he never uncovered the true author of Shakespeare’s works.

The PBS series Shakespeare Uncovered would like us to think that its programs are getting at the truth of the genius of Shakespeare. But at the point where the rubber meets the road in the life’s journey of the author, the two programs on The Taming of the Shrew and Othello never once raise the question of how the playwright came to know the world of Renaissance Italy as depicted in those two plays. Other Elizabethan and Jacobean playwrights set their plays in Italy. But works like Ben Jonson’s Volpone or John Webster’s The White Devil ultimately fail to provide any significant details about the plays’ settings in Italian Renaissance cities. The key to unlocking the secrets of Shakespeare’s genius lies in the details, and these two Shakespeare Uncovered programs fail to probe some of the most obvious and important details in the plays.

This episode’s host, Morgan Freeman, played Petruchio opposite Tracey Ullman’s Katherina in the hilarious 1990 Wild West production of The Taming of the Shrew at the Delacorte Theater in Central Park in New York City.

At the start of this documentary, Freeman gazes over the landscape of contemporary Los Angeles and informs us that the modern film industry was made possible by the efforts of “a country boy” named Will, who “started at the bottom.” With no attempt to compare the conventions of the Elizabethan public theaters with today’s movies, the program merely starts on the premise that the Elizabethan stage was the Hollywood of its day in the late 16th century. Freeman invokes the iconic anecdote of the young Shakespeare’s first job in London, holding horses outside the London theaters like a “valet parking boy.”

The program informs its audience that Shakespeare arrived in London around the year 1590, and narrator Freeman asserts that “Will was no reclusive poet. Of course, he was working in the theater with actors.” Professor Jonathan Bate suggests that The Taming of the Shrew is “possibly the very first” play written by Shakespeare. This raises major questions about how the man from Stratford could have honed his craft to produce such a polished play at this early date.

The program never mentions that two versions of this play exist — one set in Greece and a longer version set in Italy. The two plays were even given different titles. The Taming of a Shrew was published in quarto and listed in Henslowe’s famous theater diary in 1594. But the play we know as The Taming of the Shrew was not published until the First Folio was issued in 1623. Geoffrey Bullough, one of the foremost scholars of Shakespeare’s sources, sums up the dating problem with great understatement when he writes that “the date of this play is in doubt.”

The play’s framing device is an “induction” set in an alehouse in the native Warwickshire of the presumed author William Shakespeare. Professor Bate identifies the character of Christopher Sly as “a kind of representation of Shakespeare himself.” In the induction, the Lord and his entourage convince Sly that he has lived for the past fifteen years in a dream as the rogue Christopher Sly and that he is in fact a lord, who will now be pampered by servants and treated to the performance of a play. In extremely revealing lines about the scholarly qualifications of the Stratford man, Christopher Sly remarks, “the Slys are no rogues. Look in the Chronicles, we came in with Richard Conqueror” (Induction 1, 4–5).

The contempt that the author shows for Sly is apparent at the outset, as Sly confuses William the Conqueror for Richard the Lionheart. For Professor Bate, the author was using self-deprecating humor as a witty commentary on his lack of a university education. But the professor misses the point that as the audience, we are laughing at Sly, rather than with him. In this part of the program, a clip is shown of the induction scene with the actor playing Sly relieving himself, then falling into a drunken stupor, prior to becoming victim of the hoax. In the text, it is explicitly stated that Sly is the “fool” in the play. Yet Professor Bate’s astonishing conclusion is that the Christopher Sly character was an instance of the author “celebrating” his provincial background!

While the program offers a good sampling of clips from film and stage productions of Shrew, a glaring omission was the 1976 production directed by William Ball at the American Conservatory Theatre in San Francisco and subsequently archived in a DVD recording in the Broadway Theatre Archives series. Ball’s production concept was to infuse the play with the popular style of Italian Renaissance commedia dell’arte. While not altering Shakespeare’s text, the production seamlessly incorporated the stock characters and the comic business (lazzi) of the commedia dell’arte. The broad physical style and the unique comic effects of this production inadvertently demonstrate the author’s knowledge of the commedia style and the influence it exerted on his comedies. There were no commedia troupes performing in England; the author could only have experienced this style first-hand in Italy.

Here is one of the show-stopping scenes with Marc Singer and Fredi Olster as Petruchio and Kate from this landmark 1976 production available on YouTube.

A valid issue raised in Shakespeare Uncovered is the author’s consciousness of writing about the “outsider” in Shrew. The specific outsider was the woman in the Elizabethan age. As the program unfolds, it becomes clear that Katherina was not a stereotype, but a full-blooded individual, who, according to Freeman, eventually discovers equality in her relationship with Petruchio. But the role of women in Tudor society is unexplored in the program. Time and again, the commentators offer generalizations about gender issues in our own world, while ignoring the actual roles of men and women in Elizabethan England.

It is unfortunate that the program’s producers never touch on the Elizabethan court in an attempt to understand the significant role played by individual women, not the least of whom was the Queen herself. In a cocoon-like environment, a labyrinth of layers protected the Queen to ensure her privacy. But the protection was not from a praetorian guard of males. Rather, specially designated women served as buffers for the select few who were permitted entrance to the inner sanctum of Elizabeth. According to scholar Tracy Borman in her book Elizabeth’s Women, “Elizabeth was hardly ever alone. She herself admitted that she was ‘always surrounded by my Ladies of the Bedchamber and maids of honour.’ ”

Shakespeare Uncovered misses the point about how some of the female “outsiders” played significant roles in the inner world of the court. One of the fascinating studies by Borman is her detailed appraisal of Helena Snakenborg, an impoverished, Swedish-born outsider, who rose to unprecedented prominence as Elizabeth’s Maid of Honour. In her life story, Snakenborg appears to be the very incarnation of Shakespeare’s Helena in All’s Well That Ends Well. A deeper study of this world might uncover the real-life model for the role of Katherina and her relationship to the author himself — perhaps his half-sister, who went by the name of Katherine.

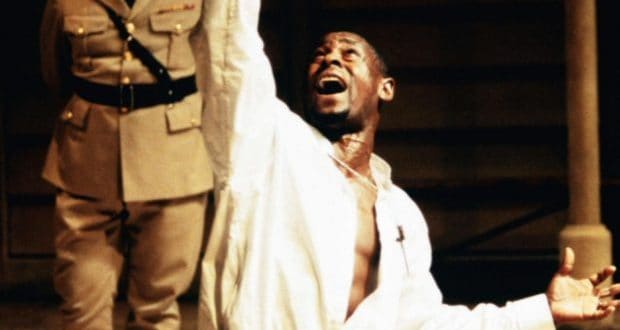

David Harewood trained at the Royal Academy of Dramatic Art and was the first black performer to play the role of Othello at the famed National Theatre of Great Britain. He is familiar to American audiences for his role as CIA Director David Estes in the Showtime series Homeland. In his compelling narration of this episode, the theme of the “outsider” is explored once again, in this instance from the perspective of race.

This program provides a good overview of celebrated productions of Othello, including those of the 19th-century African American actor Ira Aldridge, who left America because he had no opportunities to perform and was subsequently shunned in Great Britain, prior to developing a wide following on the European continent and in Russia. The famous production of American athlete-singer-actor-activist Paul Robeson, as directed by Margaret Webster in 1943, is briefly mentioned. Harewood delivers an uncanny imitation of Laurence Olivier’s vocal characterization of Othello from a virtually unwatchable film version of the 1965 stage production.

In one of the most intriguing moments of this program, Professor Jerry Brotton of the University of London identifies Mohammad al Ah-nou-ri, who paid a visit to the Elizabethan court as an ambassador from Barbary (contemporary Morocco) in the year 1600. The professor believes that al Ah-nou-ri may have served as the model for Othello. Professor Brotton even suggests that Shakespeare personally met this ambassador at the time he was writing Othello! Yet no evidence for the dating of the play or this extraordinary “meeting” is provided in the film.

Much of the program explores the motivation of Iago in “ensnaring the soul” of Othello, and it is a struggle for the commentators to articulate a clear motivation. Actor Simon Russell Beale speaks tentatively, stating that Iago “just wants to mess Othello up.” Paraphrasing one of Iago’s lines, Gail Kern Paster blandly asserts that “the reality is that he [Iago] hates him [Othello].” Yet Stephen Greenblatt underscores the remarkable realism achieved by Shakespeare in depicting the complete and sudden transformation of Othello through the machinations of Iago. In the end, the program fails to examine the Elizabethan world in order to come to terms with the unique depiction of the evil nature of Iago, and the most glaring omission is an analysis of the environment of the court.

Is it conceivable that in the Elizabethan court there could have been a schemer like Iago? The answer is an unqualified yes. The insidious attempt to drive a wedge between husband and wife was part of the dark side of the Tudor aristocracy. One of the legacies of Tudor England is our popular fascination in those piratical and nefarious creatures who would stop at nothing in their quest for power. One of the means to their ascent was by ruining the reputation of rivals.

Through multiple generations, the male members of the Dudley family had the kind of vaulting ambition that is depicted over and over in characters from the Shakespearean canon. The greatest success story of the Dudley clan was Robert, who became the favorite of Queen Elizabeth and was elevated to the title of Earl of Leicester. In alleging criminal misconduct of the highest order against the Earl of Leicester, Charles Arundell asserted that Leicester attempted “to sow and nourish debate and contention between the great lords of England and their wives …. The same he attempted between the earl of Oxford and his lady, daughter of the lord treasurer of England, and all for an old grudge he bare to her father the said Lord Treasurer.”

The result was a scandalous and nearly irreparable marriage similar to the Othello-Desdemona relationship unfolded by the author Shakespeare. For both critics and theater practitioners, one of the greatest challenges of interpreting Othello is in identifying the motivation of Iago. The careful placement of the play in the world of the Elizabethan court sheds light on the specific intent of Iago that is left ambiguous in the play.

The theme of jealousy runs through the plays, the sonnets, and the narrative poems of Shakespeare. An ancillary topic, as explored in Othello, is the loss of reputation, and it is expressed most profoundly by Cassio: “Reputation, reputation, reputation! O, I have lost my reputation! I have lost the immortal part of myself, and what remains is bestial. My reputation, Iago, my reputation!” (2.3.255–58)

Charlton Ogburn Jr. has identified how passages like this one simply leap off the page as examples of the author’s personal revelation. For Ogburn (The Mysterious William Shakespeare, Dodd, Mead & Company, 1984, 571), the author had

the capacity to stand apart from his emotions and observe them with detachment, plotting their dramatization and contriving the verbal alchemy with which he would capture, reshape, and refine reality, milling human lives, most notably his own, to artistic ends with no more compunction than Iago in manipulating his victims to his inscrutable purposes.

Unfortunately, there is no curiosity on the part of the filmmakers of Shakespeare Uncovered to explore authorial self-expression in Othello. In the final analysis, the producers of this series begin with the premise of an author writing principally as a man of the theater. But to truly uncover the creative process of the author of The Taming of the Shrew and Othello, it is essential to acknowledge that the playwright was writing his masterworks not from perspectives gleaned from a life on the stage, but by exposing his personal experience from the stage of life.

Editorial Note: Professor James Norwood holds a Ph.D. in dramatic art from the University of California at Berkeley. He taught humanities and the performing arts for 26 years at the University of Minnesota, where he also taught for a decade a semester course on the Shakespeare authorship question. Norwood’s paper, “Mark Twain and ‘Shake-speare’: Soul Mates,” presented at the 2014 SOF Annual Conference in Madison, Wisconsin, is published in Brief Chronicles.

Membership dues cover only a fraction of our budget, including all our research, preservation and programming. Please support the SOF by making a gift today!

Blue Boar Tavern: Wassail Q&A

Tuesday Dec. 17, 8pm E / 5pm P

Sign up below for event invites!