The Fall of the House of Oxford

Nina Green

Originally published in Brief Chronicles Vol. 1 (2009), pages 41–95

Edward de Vere, 17th Earl of Oxford, was born on 12 April 1550, the only son of John de Vere (1516-1562), 16th Earl of Oxford, and his second wife, Margery Golding (d.1568). The 17th Earl has been libeled as a wastrel who dissipated a vast patrimony inherited from his father. The historical documents, however, tell a far different story.1 On the contrary,

I. The fall of the house of Oxford began with the Protector Somerset’s extortion against the 16th Earl in 1548-9;

II. Sir Robert Dudley (1533-1588), later Earl of Leicester, played a sinister role immediately prior to the 16th Earl’s death in 1562, and was the only real beneficiary of the 16th Earl’s death;

III. De Vere’s inherited annual income amounted to only £2250, and he would never have received even that amount in any single year in his lifetime; and

IV. Queen Elizabeth’s mismanagement of de Vere’s wardship was a primary cause of his eventual financial downfall.

I. Somerset’s extortion against the 16th Earl in 1548-9

The fall of the house of Oxford began with the Protector Somerset’s extortion against Edward de Vere’s father, John de Vere, the 16th Earl of Oxford.

During the first years of the minority of King Edward VI (1537-1553), the young King’s uncle, Edward Seymour (c.1500-1552), Duke of Somerset, served as Protector of the Realm. In 1548-9, he abused his great power and authority to extort almost all the lands of the Oxford earldom2 from the 16th Earl under the pretext of a marriage contract.3 By his first wife, Dorothy Neville (d.1548), from whom he had been separated for several years before her death, the 16th Earl had one child who had survived infancy, his daughter Katherine de Vere (1538-1600). On 30 January 1548 Somerset obtained license from the 10-year-old King authorizing the 16th Earl to alienate4 some of his lands to Somerset,5 and on 1 and 26 February 1548 Somerset forced the 16th Earl to enter into an indenture,6 and a recognizance in the amount of £6000,7 binding him to marry his nine-year-old daughter Katherine to the youngest son of Somerset’s second marriage, Henry Seymour (1540-c.1600),8 and to transfer legal title to the lands of the Oxford earldom in fee simple9 to Somerset and his heirs by means of a fine10 before 20 May 1548.11 The circumstances of the signing of the indenture are described in a private Act of Parliament of 23 January 1552:

[U]nder the colour of administration of justice, [Somerset] did convent before himself for certain supposed criminal causes John, Earl of Oxenford, one of the King’s most loving subjects, who personally appeared before the said Duke, and then the said Duke so circumvented and coerced the said Earl of Oxenford to accomplish the desire of the said Duke (though it were unconscionable), and used such comminations12 & threats towards him in that behalf that he, the Earl, did seal & subscribe with his own hand one counterpane of one indenture devised by the said Duke & his counsel bearing date the first day of February in the second year [1548] of our said Sovereign Lord the King his reign made between the said Duke on the one party and the said Earl on the other party.13

[pullquote]It is clear from the language of the Act that Somerset used coercion to blackmail the 16th Earl into breaking the ancient de Vere entails and signing away the de Vere inheritance.[/pullquote]It is clear from the language of the Act that Somerset used coercion to blackmail the 16th Earl into breaking the ancient de Vere entails14 and signing away the de Vere inheritance, but unfortunately the Act is silent as to the precise nature of the specious “criminal causes” which Somerset alleged against the 16th Earl, and the precise nature of Somerset’s threats against him.15

This flagrant injustice against the 16th Earl was rectified by two private Acts of Parliament passed after Somerset fell from power and was beheaded on Tower Hill on 22 January 1552.16 In a lawsuit brought by the Queen against de Vere in 1571, Sir James Dyer (1510–1582) referred to the private Act of Parliament of 23 January 1552 in his judgment:

King Edward 6, having knowledge by information of his Council of the great spoil and disherison of John, late Earl of Oxford, by the circumvention, commination, coercion and other undue means of Edward, late Duke of Somerset, Governor of the King’s person and Protector of the realm and people, practised and used in his time of his greatest power and authority with the said Earl whereby all ancient lands and possessions of the earldom of Oxford within the realm were conveyed by fine and indenture anno 2 Edward 6 [1548] to the said Duke in fee, and yet indeed by a metamorphosis entailed to him and his heirs begotten on the Lady Anne, his wife, by force of a statute made anno 32 Henry 8 [1540]. . . .17

It should be noted that Dyer’s comments concerning Somerset’s “great spoil and disherison” of the 16th Earl were not mere hearsay years after the fact. Dyer, elected to Parliament in 1542, was a member of the Parliament which passed the private Act of 23 January 1552 to which he alludes, and ended his parliamentary career as speaker in the last Parliament of Edward VI in March 1553.18

As noted by Dyer in his 1571 judgment, the fine which Somerset had forced the 16th Earl to enter into resulted in a legal “metamorphosis” by which the lands of the Oxford earldom, rather than being assured to the heirs of the 16th Earl’s daughter, Katherine, and her prospective husband, Henry Seymour, instead became entailed to Somerset himself, and his male heirs by his second wife, Anne. This legal “metamorphosis” came about, as Dyer says, because of an earlier private Act of Parliament which Somerset had had passed in April 1540 by which he had disinherited his son and heir by his first marriage, John Seymour (d.1552), and had entailed his lands on his heirs by his second wife.19

As Dyer indicates, the 16th Earl’s inheritance was disastrously affected by this entail of Somerset’s. Equally disastrously affected were the rights of Somerset’s son and heir by his first marriage, John Seymour (d.1552). Numerous other interests were affected by the entail as well, since Somerset’s attainder20 for felony meant that his assets were forfeited to the Crown. For all these reasons, Parliament struggled for several months with the drafting of a private Act to strike down the 1540 entail, rejecting several amendments along the way, and not finishing the business until 13 April 1552, at the very end of the parliamentary session:21

Serious and revealing difficulties were also experienced by the government in driving through a private bill, to which the royal assent had been gained in advance, to repeal the entail of 32 Henry VIII against the Duke of Somerset’s first marriage, procured, it was stated, ‘by the power of his second wife over him’. The bill was first challenged by the Lords, who feared that such a measure might unsettle all land tenures, and was then re-drafted by the Commons who also declined to pass a supplementary bill confirming ex post facto the attainder of the Duke. Still another amendment dissolving the contract for the marriage of Somerset’s son to the daughter of the Earl of Oxford was lost by a vote of 69 to 68, while the bill for striking down the entail remained belaboured until the very end of the session when it was passed, carrying with it the forfeiture of much of the Duke’s estate to the crown. . . . Such property as Somerset had before the passage of the Act of 32 Henry VIII was to pass to John Seymour or his heirs; all acquired since was to pass to the King as a consequence of the Duke’s treason, subject to the payment of his debts, the support of the children of the second marriage, and compensation for those cheated by Somerset.22

Although the private Act of Parliament which was finally passed on 13 April 1552 struck down Somerset’s entail, that Act was in itself insufficient to undo the legal harm Somerset’s extortion had caused to the 16th Earl, and in any event it was not passed until the end of the parliamentary session. In the meantime Parliament had passed another private Act on 23 January 1552 specifically designed to rectify the injustice done to the 16th Earl by Somerset’s extortion. As indicated in the will of John de Vere (1442-1513), 13th Earl of Oxford,23 and as the 16th Earl stated in an indenture of 2 June 1562, the lands and offices of the Oxford earldom had, prior to Somerset’s extortion, passed from male heir to male heir via “ancient entails”:

Witnesseth that whereas the earldom of Oxenford and the honours, castles, manors, lordships, lands, tenements, hereditaments and other the possessions of the same earldom, together with the office of Great Chamberlainship of England, the Lieutenantship of the Forest of Waltham and the keeping of the house and park of Havering, have of long time continued, remained, and been in the name of the Veres from heir male to heir male by title of an ancient entail thereof made long time past . . . .24

The fine of 10 February and 16 April 154825 which Somerset had extorted from the 16th Earl cut off the ‘ancient entails’, and Parliament either could not, or would not, restore them. Instead, by a private Act passed on 23 January 1552, Parliament declared the indenture of 1 February 1548 and the recognizance of £6000 of 26 February 1548 extorted from the 16th Earl by Somerset void, and decreed that the fine covering lands which the 16th Earl had held under the ‘ancient entails’ was now deemed to be to the 16th Earl’s use:26

The King his most excellent Highness for the great zeal which he beareth & intendeth unto the true & perfect execution & administration of justice committed unto his Highness’ charge from Almighty God, not willing to permit or suffer the said now Earl or any other his loving subjects to be undone or disherited by any such wresting, circumvention, compassing, coercion, enforcement, fraud or deceit as the said Duke hath committed, practised & done unto the said now Earl in manner & form as is above remembered, is therefore pleased & contented that it be enacted by his Majesty with the assent of the Lords Spiritual & Temporal and the Commons in this present Parliament assembled, and by authority of the same, that the said indenture bearing date the first day of February in the said second year of our said Sovereign Lord the King his reign, and the said recognizance of the said sum of six thousand pounds . . . shall be of no force or effect in the law, but shall stand, remain & be annihilate, frustrate & void to all intents, constructions & purposes as if the said indenture & recognizance & every of them had never been had or made;

And be it further enacted by the said authority that the said fine levied of the said honours, castles, manors, lands, tenements & hereditaments mentioned & comprised in the same fine shall be adjudged, deemed, accepted, reputed & taken to be from the time of the same fine levied to the use of the said now Earl for term of his life without impeachment of waste, & after his decease to the use of the eldest issue male of the body of the same now Earl lawfully begotten & of the heirs males of the body of that issue male begotten, and for default of such issue to the use of the right heirs of the said now Earl forever, and to none other use, uses or intents;27

In his judgment in 1571 in the lawsuit brought by the Queen against de Vere mentioned above, Dyer reiterates this legal position, stating that the Act had declared the indenture of 1 February 1548 (‘the said indenture of conveyances’) void, and had deemed the fine to be to the use of the 16th Earl and his heirs:

King Edward 6 . . . was pleased that it should be enacted by authority of Parliament that the said indenture of conveyances should be utterly void, and that the said fine should be deemed to be to the use of the same Earl for term of his life without impeachment of waste, the remainder in use to the eldest issue male of his body lawfully begotten, and to the heirs male of the body of that issue male lawfully begotten, and for default of such issue to the use of the right heirs of the said Earl forever, and to no other uses save to all persons other than the King and his heirs and successors and all other lords and their heirs of whom any of the said lands were holden, such right etc., which exception was to take away the escheats or wardships28 that might grow to the King or other lords by th’ attainder of felony of the said Duke or by his death, dying seised but of a state tail, as doth appear by the Act.

Dyer then explains the legal consequences:

Item, the rest of all the particular estates and interests of the brothers29 executed, and of the father’s wife, is expressly appointed to the father during his life, remainder to the son etc., as above, and thus by the Act he shall be adjudged in as purchaser, and not as heir by descent . . . But of all the lands that were given in tail by King Henry 8, the Queen shall have the whole in ward etc.30

Thus, after the fine of 10 February 1548 and the passage of the private Act of Parliament of 23 January 1552, the 16th Earl and his heirs did not hold the lands comprised in the fine as they had held them under the “ancient entails.” In fact, according to Dyer’s judgment, it would appear that the lands comprised in the fine and covered by the Act did not come to de Vere by descent at all, but rather as a purchaser.31

Additional clauses in the private Act of Parliament of 23 January 1552 attempted to right the wrongs done to others besides the 16th Earl whose interests had been affected by the fine, including the 16th Earl’s second wife, two of his brothers, his daughter Katherine, and the King himself. The Act contained a saving clause which expressly dealt with the King’s right to wardship:

Provided always and be it enacted by the authority aforesaid that the King our Sovereign Lord, his heirs & successors, and all & every other person & persons of whom the premises or any parcel thereof be holden by any rent or service, shall have & enjoy all & singular such rents, tenths, tenures, seigniories & services, wardships, liveries & primer seisins of, in, out & to the premises & every parcel thereof as our said Sovereign Lord the King, his heirs & successors, and the said other person & persons & their heirs & every of them ought, might or should have had as if the said now Earl were thereof seised in fee simple and should die of the third part thereof seised in fee simple.32

This saving clause ostensibly preserved the King’s rights in the lands comprised in the fine of 10 February 1548 during the 16th Earl’s lifetime, and assumed even greater significance when the 16th Earl died leaving a minor heir, Edward de Vere, bringing the King’s prerogative rights33 into play.

Since 1540, the King’s prerogative right to revenue from the lands of an underage heir had been limited in practical terms by the Statute of Wills,34 and “The bill concerning the explanation of wills,”35 which allowed a tenant in chief of the Crown who held an “estate of inheritance” (defined in the legislation as an “estate in fee simple”) by knight service36 to dispose in his last will and testament of two-thirds of his lands, leaving the full profits of the remaining third to the Crown for its prerogative rights of “custody, wardship and primer seisin.”37 From 1540 on, therefore, before the Crown could exercise its prerogative rights, the father of the heir must have died seised of at least an acre of land as a tenant in chief of the Crown by knight service. It should be noted that the clause in the private Act of Parliament of 23 January 1552 which preserves the King’s rights makes no finding that the 16th Earl held any of the lands comprised in the fine of 10 February 1548 as a tenant in chief of the Crown by knight service. It leaves that issue entirely open, merely stating that if the 16th Earl does hold the lands comprised in the fine of the King by “any rent or service,” the King will have all such rights as he would have had had the 16th Earl been seised of the lands in fee simple and died seised of the third part in fee simple.38

The obvious question then becomes whether, as a result of the 1548 fine which gave Somerset legal title to the 16th Earl’s lands in fee simple and transferred to him the tenures by which the 16th Earl had held them from the Crown, Somerset had died in 1552 holding the lands comprised in the fine as a tenant in chief of the Crown by knight service.39 It could be argued that he did. The Act attempts to get around this legal difficulty by making the deeming clause retroactive to the date on which the fine was levied in 1548 (“shall be adjudged, deemed, accepted, reputed & taken to be from the time of the same fine levied to the use of the said now Earl”). But the fact remains that before the deeming clause was enacted,40 Somerset had already died holding the lands comprised in the fine by a tenure which triggered the King’s prerogative rights. If Somerset had died holding the lands comprised in the fine as a tenant in chief of the Crown by knight service, it seems unlikely that the tenures could somehow be transferred back to the 16th Earl retroactively merely by a deeming clause. Moreover, as noted above, Sir James Dyer held in his judgment in 1571 that the lands comprised in the fine did not come to de Vere by descent, but as a purchaser, a decision which implies that Dyer considered that the tenures had not been transferred back to the 16th Earl by the deeming clause.41 It would thus appear that the saving clause in the Act did not after all provide a legal basis for the Queen’s claim to de Vere’s wardship ten years later insofar as the lands comprised in the fine were concerned, because the lands comprised in the fine were not held by the 16th Earl as a tenant in chief of the Crown by knight service when he died.42

It will likely never be known what motivated Somerset to wield his power so harshly against the 16th Earl in early 1548.43 The event which gave him the opportunity to do so is, however, quite clear. The 16th Earl’s wife, Dorothy Neville, died on 6 January 1548.44 The 16th Earl was suddenly a widower with no wife by whom he might hope to produce a future male heir. His only child was his daughter, Katherine, and Somerset acted swiftly to secure her as a bride for his youngest son, Henry Seymour. Under the “ancient entails,” however, the 16th Earl’s lands would pass on his death to the next male de Vere heir. In order for Somerset to obtain the 16th Earl’s lands, it was necessary for him to break the “ancient entails” by means of the legal documents which he speedily proceeded to extort from the 16th Earl, foremost among them the King’s license to alienate of 30 January 1548.45 The lands were then settled, to public appearances, on the heirs of young Katherine and Henry via the indenture of 1 February 1548, but by a “legal metamorphosis” were in reality secretly entailed to Somerset and his heirs, as Dyer explains, by the operation of the fine of 10 February 1548 in conjunction with the private Act of Parliament which Somerset had had passed in April 1540.

However, a few months after he had submitted to Somerset’s extortion in early 1548, the 16th Earl boldly attempted to frustrate Somerset’s purposes by secretly marrying Margery Golding on 1 August 1548.46 The inheritance system was based on primogeniture,47 and the 16th Earl clearly hoped by this second marriage to produce a male heir. This would not in itself have frustrated the legal steps Somerset had taken to appropriate the de Vere inheritance to the heirs of the marriage of his young son, Henry Seymour, and the 16th Earl’s nine-year-old daughter, Katherine de Vere, but it was an obvious and necessary first step.48 In the summer of 1548, Somerset was still at the height of his power, and the 16th Earl took a serious risk in entering into this secret marriage contrary to Somerset’s wishes. Having lost almost everything already, however, the 16th Earl must have considered that he had little more to lose, and that taking this bold step was worth the risk. In any event, once the marriage was solemnized, it could not be undone,49 even by Somerset, and on 12 April 1550, it produced the male heir on which the 16th Earl had pinned his hopes.50

Meanwhile, Somerset’s opponents within the council had brought about his first fall from power. Several months prior to de Vere’s birth, Somerset was imprisoned in the Tower, and his deposition as Lord Protector was confirmed by an Act of Parliament on 14 January 1550. Despite this serious setback, Somerset was pardoned and regained the young King’s favor, but his political comeback was short lived. He was arrested for high treason on 16 October 1551, tried on 1 December, convicted of felony, and beheaded at Tower Hill on 22 January 1552.51

[pullquote]The execution of Northumberland and the imprisonment of his sons which resulted in part from the 16th Earl’s support of Mary sowed seeds of animosity toward the house of Oxford on the part of Northumberland’s son, Sir Robert Dudley, later Earl of Leicester and Queen Elizabeth’s favorite.[/pullquote] Although the rapacious Somerset could do him no more harm, and although he now had a male heir, the 16th Earl’s fortunes failed to prosper because the events which followed Somerset’s execution gave rise to enmity between the de Vere and Dudley families. The political vacuum after Somerset’s fall had been filled by the rise to power of John Dudley (1504-1553), Duke of Northumberland. Northumberland prompted the young King Edward VI to alter the succession in favour of Northumberland’s daughter-in-law, Lady Jane Grey, and when the King died on 6 July 1553, Northumberland had Lady Jane proclaimed Queen.52 The 16th Earl did not support Northumberland’s choice. Instead, after some persuasion he rallied his followers to Queen Mary, and was instrumental in her accession to the throne.53 However, his service to the new Queen was not rewarded. The 16th Earl seems to have been regarded with suspicion by Mary and her advisors, and received no preferment during her reign. More importantly, however, the attainder and execution of Northumberland and the imprisonment of his sons which resulted in part from the 16th Earl’s support of Mary sowed seeds of animosity toward the house of Oxford on the part of Northumberland’s son, Sir Robert Dudley (1533-1588), later Earl of Leicester and Queen Elizabeth’s favorite. Although Sir Robert Dudley gave few overt signs of his enmity, it seems clear from his lifelong opposition to de Vere’s interests that he bore the house of Oxford a bitter and long-standing grudge.54

After the death of Queen Mary in 1558, the crown came to her sister, Elizabeth. As early as the eve of the new Queen’s accession, Sir Robert Dudley was already considered one of her “intimates.”55 His rise to power had begun.

II. Sir Robert Dudley’s sinister role in events prior to the 16th Earl’s death

“‘A poisons him i’th’ garden for’s estate”

Four years after the accession of Queen Elizabeth, the 16th Earl died on 3 August 1562. His death was sudden and unexpected. On 1 April 1562 the 16th Earl took recognizances in person from Robert Christmas (d.1584) and John Lovell,56 and in midsummer 1562, in the company of Sir John Wentworth (1494-1567), he took pledges in person from various individuals.57 Yet only a few weeks after performing the latter of these public duties, and only a month after having appeared personally in the Court of Chancery in London on 5 July 1562 to acknowledge two separate indentures,58 he was dead.

In the weeks immediately prior to his death, the 16th Earl had entered into three legal agreements with far-reaching consequences—an indenture dealing with the settlement of his lands,59 an indenture arranging a marriage contract for his son and heir,60 and a last will and testament.61 All three of these legal agreements prominently involved Sir Robert Dudley.

As mentioned above, from 1552 until his death the 16th Earl held the lands comprised in the fine under the deemed use mandated by the Act of Parliament of 23 January 1552 rather than under the “ancient entails” by which he had originally inherited them.62 On 2 June 1562 the 16th Earl attempted to recreate something resembling the “ancient entails” by entering into an indenture which advanced or confirmed the interests in the 16th Earl’s lands of his wife, Margery (nee Golding), his only son and heir, his son’s future wife, “Lady Bulbeck,” his three brothers, Aubrey, Robert and Geoffrey Vere, and the future male heirs of the Oxford earldom.63

[pullquote]Immediately prior to his death, the 16th Earl entered into 3 legal agreements—(1) an indenture dealing with the settlement of his lands, (2) an indenture arranging a marriage contract for his son, and (3) a last will and testament. All three legal agreements prominently involved Sir Robert Dudley. [/pullquote]To recreate the entails, it was necessary for the 16th Earl to appoint one or more trustees who would hold the lands to various uses. He chose for that purpose his nephew, Thomas Howard (1538-1572), 4th Duke of Norfolk, his brother-in-law,64 Sir Thomas Golding (d.1571), and Sir Robert Dudley,65 to whom the 16th Earl was not closely related by either blood or marriage,66 and whom he had good reason to distrust because of the enmity engendered between the Dudleys and the de Veres when the 16th Earl had supported Mary as Queen rather than Northumberland’s choice, Robert Dudley’s sister-in-law, Lady Jane Grey.

It seems evident that the 16th Earl chose each of the three trustees to represent and protect the interests of a particular person or persons. In that regard, the appointment of two of the trustees poses no problem. Sir Thomas Golding (d.1571) was the eldest brother of the 16th Earl’s wife, Margery Golding, while Norfolk was a first cousin of the 16th Earl’s son and heir, and the nephew of the 16th Earl’s three brothers. It was natural that the 16th Earl would appoint Sir Thomas Golding and the Duke of Norfolk to represent, respectively, the interests of his wife, and of his son and brothers. But what induced the 16th Earl to appoint Robert Dudley as a trustee? Whose interests was Dudley intended to represent? It seems clear that the 16th Earl appointed Dudley as a trustee to protect the interests of the future “Lady Bulbeck.” But who was “Lady Bulbeck?”

The answer to that question can be found in the second of the three documents entered into by the 16th Earl in the summer of 1562. On 1 July 1562 the 16th Earl entered into an indenture67 with Dudley’s brother-in-law, Henry Hastings (1536?-1595), 3rd Earl of Huntingdon, for a marriage between the 16th Earl’s twelve-year- old son and heir and one of the sisters of the Earl of Huntingdon, either Elizabeth or Mary,68 provided that both bride and groom gave their own consents to the marriage upon reaching the age of eighteen.69 Had he not already received prior assurances that Dudley’s brother-in-law, Huntingdon, was prepared to enter into a marriage contract which would unite the two families, it is highly unlikely that the 16th Earl would have appointed Sir Robert Dudley as a trustee in the indenture of 2 June 1562. Negotiations for the marriage must therefore have been successfully concluded before the indenture of 2 June 1562, which provided for the future Lady Bulbeck’s jointure, and the indenture of 1 July 1562, which formally settled the terms of the marriage agreement. The fact that the indenture of 2 June 1562 providing for the future Lady Bulbeck’s jointure, and the indenture of 1 July 1562 formally settling the terms of the marriage agreement, were both acknowledged by the 16th Earl in Chancery on 5 July 1562, four days after the signing of the marriage contract,70 supports this conclusion.

These circumstances pointing to the marriage negotiations having been concluded before 2 June 1562 suggest that Sir Robert Dudley was directly involved in them, and that it was by helping to arrange the marriage that he gained the 16th Earl’s confidence sufficiently to be appointed as one of the three trustees of the 16th Earl’s lands under the indenture of 2 June 1562 to represent the interests of “Lady Bulbeck,” the sister of his brother-in-law, the Earl of Huntingdon. The appointment of Dudley as a trustee in the indenture served as recognition that he had been a prime mover behind the marriage and that he had perhaps also been instrumental, as her favourite, in gaining the Queen’s consent. Both the future “Lady Bulbeck” and her brother, the Earl of Huntingdon, had claims to the throne through their mother, Katherine Pole,71 and it is highly unlikely that a marriage which involved a possible claimant to the throne would have been contracted without the Queen’s prior knowledge and consent.72

Finally, on 28 July 1562, only five days before his death, the 16th Earl made a will in which he named Sir Robert Dudley as a supervisor.73 Under normal circumstances, the executors appointed by the testator had the primary duty of carrying out the testator’s intentions, and the role of a supervisor was minimal. However, in the case of the 16th Earl’s will, administration was granted on 29 May 1563 to only one of the six executors named in the will, the 16th Earl’s former servant, Robert Christmas (d.1584), who by that time was either already in, or shortly about to enter, Sir Robert Dudley’s service.74 Five of the six executors, including Edward de Vere and his mother, Margery Golding, took no part in the administration of the will, and Sir Robert Dudley’s role thus became a highly significant one. It is difficult to escape the conclusion that the other five executors were forced out, and that Robert Christmas, as sole administrator, took direction from Sir Robert Dudley as supervisor of the 16th Earl’s will. It was not until 19 April 1570 that de Vere was finally joined with Robert Christmas in the administration of the will.75

[pullquote]A new will only 5 days before his death has been construed as evidence that the Earl was putting his affairs in order because he was ill and expecting to die shortly. However, this conclusion is strongly contradicted by the documents themselves. [/pullquote]The making of a new will only five days before his death on 3 August 1562 has been construed by some as evidence that the Earl was putting his affairs in final order because he was in ill health and expecting to die shortly. However, this conclusion is strongly contradicted by the documents themselves. In the first place, the opening paragraph of the will contains none of the language denoting final illness which was usual in the Tudor period when a testator was on his deathbed (“being sick/weak in body but of good and perfect remembrance”). The opening paragraph of the will merely states that the 16th Earl was “of whole and perfect mind” at the time of the making of the will.

Secondly, it was necessary for the 16th Earl to bring his will into line with the indenture of 2 June 1562. As mentioned earlier, the indenture provided a jointure for the future Lady Bulbeck. It also augmented the jointure of the 16th Earl’s second wife, Margery Golding, and its provisions in that regard were incompatible with the 16th Earl’s previous will, made ten years earlier on 21 December 1552.76 Because of Somerset’s extortion, the 16th Earl had been unable to provide a jointure for his wife, Margery Golding, at the time of their secret marriage in 1548. The private Act of Parliament of 23 January 1552 had authorized the Earl to assign specified manors in his will to his second wife, Margery Golding, as her jointure. By his will of 21 December 1552, the 16th Earl assigned all the specified manors to his wife, but added four other properties to her jointure by virtue of another provision of the Act which authorized him to alienate a limited number of specified manors.77 In the indenture of 2 June 1562, the 16th Earl eliminated three of the four additional properties which he had assigned to Margery Golding in the 1552 will, and supplemented her jointure by the addition of eleven other properties.78 The 1552 will thus assigned certain properties to Margery Golding while the 1562 indenture assigned other properties to her. This discrepancy constituted a sufficient and compelling reason by itself for the 16th Earl to execute a new will on 28 July 1562 in order to bring the provisions in his will for Margery Golding’s jointure into line with the new provisions in the indenture of 2 June 1562.

Moreover, many other provisions in the 16th Earl’s will of 21 December 1552 were out of date. Two executors named in the 1552 will had died, and no supervisors had been appointed. The 1552 will contained an obsolete provision for a marriage portion for the 16th Earl’s then-unmarried daughter, Katherine de Vere (1538-1600), who had since married Edward (1532?-1575), 3rd Lord Windsor, but contained no provision for a marriage portion for his daughter Mary de Vere (d.1624), who had been born after the will was executed in 1552. There were obsolete bequests in the 1552 will to the 16th Earl’s now-deceased brother-in-law, Sir Thomas Darcy (1506- 1558), and to a long list of servants, a number of whom would have died or left the 16th Earl’s service in the ten years which had passed since the making of the will.

It thus seems clear that the making of a new will by the 16th Earl in the late summer of 1562 had nothing to do with an expectation on his part that he would die shortly, and everything to do with bringing all his financial affairs into line with the marriage contract he had just negotiated for his son and heir and the indenture of 2 June 1562 he had just executed to provide a jointure for his son’s prospective bride.

It is also important to note that by its very nature the marriage contract was a forward-looking agreement which depended on the 16th Earl being alive until his son was in a position to marry six years later, when he reached the age of eighteen. Thus, the provisions of two key clauses in the marriage contract itself constitute evidence that the 16th Earl was not in ill health and expecting to die in the summer of 1562. The first of these clauses provides that the marriage will take place within a month of the date on which de Vere reaches the age of eighteen:

First, the said Earl of Oxenford doth covenant, promise and grant for him, his heirs, executors and administrators, to and with the said Earl of Huntingdon, his heirs, executors and administrators, by these presents that the said Lord Bulbeck, when he shall accomplish the age of eighteen years, shall within one month after marry and take to wife the said Lady Elizabeth or Lady Mary, sister of the said Earl of Huntingdon, if the said Lord Bulbeck and Lady Elizabeth or Lady Mary, whom the said Lord Bulbeck shall elect and choose to marry, will thereunto consent and agree, and the laws of God will it permit and suffer.

The second of these clauses stipulates that if the 16th Earl dies before the marriage can take place, any moneys paid pursuant to the contract by the Earl of Huntingdon must then be repaid within one year of the 16th Earl’s death:

And farther that if it shall happen the said Earl of Oxenford to decease before the said marriage had and solemnized, by reason whereof the same marriage cannot take effect without further charge to the said Earl of Huntingdon . . . that then within one whole year next after such death of the said Earl of Oxenford . . . the said Earl of Oxenford, his heirs, executors or assigns, shall well and truly content and repay or cause to be repaid unto the said Earl of Huntingdon, his executors or assigns, all such sums of money as by the same Earl of Oxenford, his executors or assigns, shall before that time have had and received of the said Earl of Huntingdon, his executors or assigns, in consideration of the said marriage, and also by good, sufficient and lawful means shall release, acquit, exonerate and discharge the same Earl of Huntingdon, his heirs, executors and administrators, of all such other sums of money covenanted, agreed or intended by these presents to be paid to the said Earl of Oxenford by the said Earl of Huntingdon, and then or after to become due to be paid and not paid for and in consideration of the said marriage or by reason of any agreement confirmed in these presents.

If any evidence were needed that the 16th Earl had no expectation whatever that he would be dead only a month after this contractual arrangement for his son’s marriage was entered into, this clause supplies it. The marriage contract depended by its very nature on the 16th Earl being alive for the next six years, and contained a very specific provision that any moneys paid by the Earl of Huntingdon under it must be repaid if the 16th Earl were to die. Neither the 16th Earl nor the Earl of Huntingdon would have entered into the marriage contract if it were thought the 16th Earl would soon die.

The two clauses in the 16th Earl’s indenture of 2 June 1562 entailing lands on de Vere’s future bride, “Lady Bulbeck,”79 are also strongly predicated on the assumption that the marriage would take place, and therefore suggest that the 16th Earl had no expectation that he would soon be dead. The first clause provides that certain lands will come to Lady Bulbeck immediately after the marriage, and after her death will go to Edward de Vere.80 The second clause provides that certain lands will come to her after the death of the 16th Earl, and after her death will, also, go to Edward de Vere.81 Thus, one clause provides for lands which will come to Lady Bulbeck immediately upon marriage to Edward de Vere during the 16th Earl’s lifetime, while the other provides for additional lands which will come to her after the marriage and after the 16th Earl’s death. They are clearly predicated on the expectation that the 16th Earl would be alive six years hence to see the marriage take place. It would have been pointless for the 16th Earl to have entered into an indenture containing these clauses had he been in ill health and expecting to die shortly.

[pullquote]It is revealing to view these 3 legal documents from the perspective of Sir Robert Dudley’s financial position in 1562. Dudley was already the favorite of Queen Elizabeth. However, his finances were in dire straits.[/pullquote]Nonetheless, within two months, the 16th Earl was dead, and the suspicion cannot be avoided that Dudley, who was so extensively involved in all the 16th Earl’s affairs that summer, had some ominous foreknowledge of the 16th Earl’s death which the 16th Earl himself did not have. It is therefore revealing to step back and view these three legal documents from the perspective of Sir Robert Dudley’s financial position in 1562. Dudley was already the favorite and reputed lover of Queen Elizabeth. However, he was still a mere knight, and his finances were in dire straits.82 It is not an exaggeration to state that when the 16th Earl died on 3 August 1562, Robert Dudley was impecunious. The Dudley lands had been forfeited on his father the Duke of Northumberland’s attainder and execution, and although Robert Dudley and his brothers were restored in blood in the first Parliament after Queen Elizabeth’s accession in 1558, it was on condition that they surrender any claim to Northumberland’s lands and offices.83 Under these circumstances, the Queen could not shower largess upon Sir Robert Dudley without incurring criticism, particularly from members of the upper nobility. However, should Sir Robert Dudley suddenly become possessed of financial resources and status by his own means, additional preferments conferred on him by the Queen would not excite as much adverse comment, particularly if he were to come by those financial resources by way of an indenture in which he was joined as a party with one of the highest-ranking members of the nobility, Thomas Howard, 4th Duke of Norfolk, as was the case with the 16th Earl’s indenture appointing Dudley and Norfolk as co-trustees.

With these legal documents in place, and Dudley involved in all three of and positioned to benefit from them, the 16th Earl’s speedy demise would seem to have been inevitable. To put the matter bluntly, did Sir Robert Dudley think to himself that if the 16th Earl were dead and his son a ward, he could easily persuade the Queen to grant him the 16th Earl’s lands during the wardship, and that any public objection could easily be silenced by the fact that he been appointed by the 16th Earl as a supervisor of his will and one of the trustees in the indenture of 2 June 1562? Did Sir Robert Dudley, almost before the ink was dry on the 16th Earl’s will, arrange to have the 16th Earl “poisoned i’th’ garden for’s estate,” as Hamlet remarks in the play within the play?84 Subsequent events have made it clear that the 16th Earl’s death was disastrous for everyone directly affected by it with the notable exception of Dudley. The primary beneficiary—in fact almost the only real beneficiary—of the 16th Earl’s death was Sir Robert Dudley.85 Four hundred years have passed, and the truth will never be known. However, the facts revealed by the historical documents alluded to in the foregoing paragraphs suggest that it would not have been unreasonable for de Vere to have entertained suspicions of foul play in the death of his father, nor, as Shakespeare, to have written a play about his suspicions, casting Dudley in the part of the usurper, King Claudius.

III. Edward de Vere’s inherited annual income of £225086

After the 16th Earl’s death on 3 August and his burial on 31 August, matters moved quickly. The Earl’s twelve-year-old son and heir was brought to London on 3 September to live at Cecil House in the Strand in the care of Sir William Cecil (1521- 1598), later Lord Burghley, the Queen’s Principal Secretary and Master of the Wards. De Vere had become Queen Elizabeth’s ward.

Before dealing with the Queen’s management of de Vere’s wardship, however, it is necessary to establish the amount of net yearly revenue from lands and offices de Vere inherited from his father, in order to establish the value of his wardship to the Queen.87

[pullquote]It is unfortunate that so much misinformation has been promulgated concerning the amount de Vere inherited from his father, as there is clear evidence of it in several extant documents.[/pullquote]It is unfortunate that so much misinformation has been promulgated concerning the amount de Vere inherited from his father, as there is clear evidence of it in several extant documents.88 The starting point is the 16th Earl’s own inheritance. The net yearly revenue from lands which the 16th Earl himself inherited from his father, the 15th Earl, was £1927 15s 6-3/4d. Thus, in round figures the 16th Earl inherited lands which generated net yearly revenue of somewhat less than £1930, and during his lifetime he sold several of those manors, thus decreasing his revenue stream.89

Twenty-two years later, just prior to his death, the 16th Earl covenanted in the marriage contract with the Earl of Huntingdon of 1 July 1562 that the net yearly revenue from his lands, including £800 worth of net yearly revenue which would not come into possession of his heir, until certain life interests, and in one case the term of 21 years, had expired, was £2000 per annum. It should be noted that the 16th Earl did not include in this figure the net yearly revenue from the office of Lord Great Chamberlain.90 The Earl of Huntingdon was a prudent man who would have taken care to inform himself before entering into a marriage contract on behalf of his sister, and since he clearly accepted the round figure of £2000 per annum covenanted by the 16th Earl, there would appear to be little reason for modern historians to dispute it. The wording of the relevant clause is as follows:

And that also he, the same Earl of Oxenford, shall leave and assure by good and lawful conveyance in the law unto the said Lord Bulbeck and his heirs males of his body, after the death of Dame Margery, Countess of Oxenford, now wife of the said Earl, and after the deaths of the brethren of the same Earl of Oxenford and their wives, and after twenty and one years fully expired after the death of the said Earl of Oxenford, lands, tenements and hereditaments in possession and reversion of the clear yearly value of two thousand pounds of lawful money of England over and above all charges and reprises of lands not improved within twenty years last past nor hereafter to be improved, that is to say, in possession immediately after the death of the said Earl, one thousand and two hundred pounds, and in reversion depending only upon the lives of the said Countess and brethren of the said Earl and their wives and upon the said 21 years, to the clear yearly value of eight hundred pounds over and above the said one thousand and two hundred pounds.91

The net yearly revenue in the inquisition post mortem92 taken on 18 January 1563 after his death is consistent with the 16th Earl’s valuation of £2000 per annum in the marriage contract, allowing for the fact that the valuation in the marriage contract is a round figure while the valuation in the inquisition post mortem is a detailed breakdown of the net yearly revenue manor by manor, and that the inquisition post mortem includes an additional £106 13s 4d in net yearly revenue from the office of Lord Great Chamberlain. The net yearly revenue from all the 16th Earl’s lands and offices in the inquisition post mortem totals £2187 2s 7d.93

An undated official document, TNA SP 12/31/29, ff. 53-55, which appears to have been compiled about the same time as the inquisition post mortem, provides a comparable total for the net yearly revenue from the lands and offices inherited by de Vere. After minor arithmetical errors and the omission of the £66 yearly rent payable to the Crown for Colne Priory have been corrected, the net yearly revenue amounts to £2255 1s 9d. It should be noted that this document gives the same figure of £106 13s 4d for the office of Lord Great Chamberlain as does the inquisition post mortem.

Another official document tells a similar story, and the fact that it is an accounting document prepared by the Court of Wards vouches for its accuracy. TNA WARD 8/13 accounts for the net yearly revenue of de Vere’s lands from 29 September 1563 to 29 September 1564, i.e., the year after his death, and the total from all lands and offices differs only slightly from the figures given in the two documents already mentioned. The net yearly revenue of all the 16th Earl’s lands and offices given in TNA WARD 8/13, including £106 13s 4d for the office of Lord Great Chamberlain, totals £2233 13s 7d.

There is thus not a great deal of difference in figures for net yearly revenue among these four documents. If net yearly revenue from the office of Lord Great Chamberlain were added to the round figure of £2000 given by the 16th Earl for his lands, the total would be £2103 13s 4d. The total in the inquisition post mortem is £2187 2s 7d, that in TNA WARD 8/13 is £2233 13s 7d, while that in SP 12/31/29 is £2255 1s 9d. It thus seems safe to assess de Vere’s net yearly revenue from all inherited lands and offices at approximately £2250.

Other documents setting out revenue from the 16th Earl’s lands in individual counties confirm the figures given in the four documents already discussed which account for revenue from all counties and sources.94 The most significant of these is the feodary95 John Glascock’s survey of all the 16th Earl’s lands in Essex, which amounted to almost half the 16th Earl’s total landholdings.96 Feodaries were officials of the Court of Wards, and the Court relied heavily on their surveys for an accurate valuation of the net yearly revenue generated by the lands to be taken into wardship. Bell says, for example, that:

The real significance of the feodaries’ surveys as a cause of increased productivity [in the Court of Wards] lay in the higher values found in them than in the inquisitions post mortem.97

Hurstfield makes a similar claim:

Of the three surveys before him the Master [of the Court of Wards] invariably placed the greatest reliance upon the feodary’s survey. The inquisition post mortem might establish that there was a wardship but the feodary’s survey determined its value.98

That being the case, the fact that the figures for individual manors given in Glascock’s survey of the 16th Earl’s lands in Essex are virtually identical to those found in TNA WARD 8/13 suggests very strongly that the values given in those documents accurately represent the amounts at which the 16th Earl’s lands were rented out at the time of his death.

Additional evidence suggesting that the net yearly revenue from the lands inherited by de Vere was approximately £2250 is found in documents which indicate that the fine for livery levied by the Court of Wards when he was granted licence to enter on his lands by the Queen’s letters patent of 30 May 157299 was £1257 18s 3/4d.100 There were two methods by which a ward could sue livery101 in order to regain possession of his lands from the Queen on reaching the age of majority, a general livery and a special livery. When a ward sued a general livery, the fine levied was half the annual rental value of his lands.102 Thus, if de Vere had sued a general livery,103 the fine of £1257 18s 3/4d would indicate that the net yearly revenue from his inherited lands was double that amount, i.e. approximately £2500. However the suing of a general livery was a cumbersome procedure, and a more streamlined procedure known as a special livery was also available. If a ward chose to sue a special livery, however, the Crown “charged a heavy price for the privilege.”104 Thus, if de Vere sued a special livery, the fine of £1257 18s 3/4d represents more than half the net yearly revenue from his lands, indicating that the net yearly revenue was probably closer to £2250, as stated in the other extant documents, than to £2500.

An exception to both these procedures was a “special grant by the Crown absolving the heir from the elaborate process of suing livery.”105 The Queen’s letters patent of 30 May 1572 suggest that de Vere was granted this exception, perhaps because his income had been kept from him for an entire year, presumably while the Queen was litigating her claim against him for the revenue from his mother’s jointure after her death. The letters patent appear to grant de Vere license to enter on his lands without suing livery:

[I]mmediately, without any proof of his age & without any other livery or prosecution of his inheritance or of any parcel thereof to be prosecuted out of our hands [+& those] of our heirs or successors according to the course of procedure of our Chancery, or according to the law by the course of procedure of our Court of Wards & Liveries or the law of our land of England, or by any other manner, might licitly & safely be able to enter, go into & seise all & singular the honours, castles, lordships, manors . . . .

It is unlikely that the Queen would have granted this extraordinary privilege without levying an even higher fine than that which was levied for the privilege of suing a special livery, and it thus seems that the fine of £1257 18s 3/4d levied against de Vere represents more than half the total annual rental value of his lands, whether the letters patent are for the suing of a special livery or whether they grant de Vere an exemption from suing livery.

The combined evidence of the extant documents thus indicates that de Vere inherited lands and offices worth approximately £2250 per annum, and in fact TNA WARD 8/13, the most comprehensive of the official documents, gives the total yearly revenue of all de Vere’s lands and offices, including the office of Lord Great Chamberlain, as £2233 13s 7d in the year following his father’s death.

Annual revenue of £2250 did not constitute a large inheritance for a nobleman,106 particularly a nobleman destined to live at court. The lifestyle of a courtier could not be maintained without preferment from the Queen, something de Vere never received.107

Furthermore, de Vere would never at any time in his life have received the full £2250 in net yearly revenue from his inherited lands and offices, (1) because of his wardship; (2) because of the fact that, as stated in the marriage contract of 1 July 1562, £800 worth of his inherited lands were held in reversion;108 (3) because of the terms of his father’s will, which set aside the revenue from certain lands for 20 years for payment of his debts and legacies.

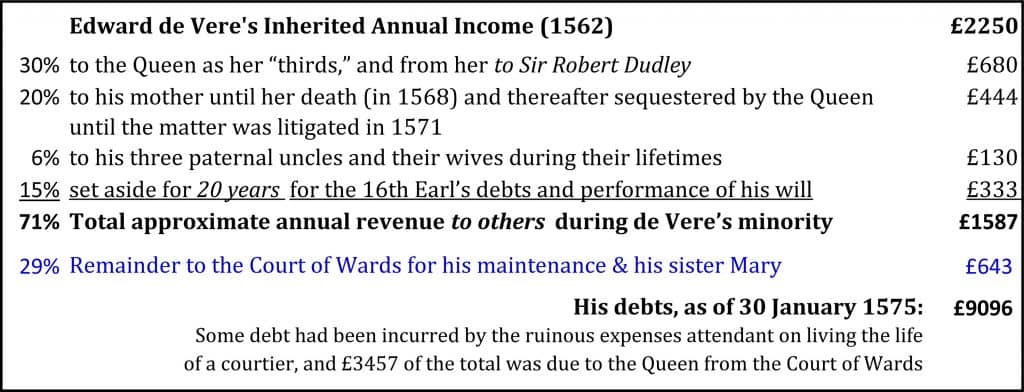

Thus, during de Vere’s wardship, £680 18s 2-3/4d per annum,109 or 30% of his total revenue, went to the Queen as her “thirds,” and from the Queen to Sir Robert Dudley under a grant of 22 October 1563, discussed more fully below.

Of the lands held in reversion, until her death on 2 December 1568110 his mother Margery Golding, the widowed Countess of Oxford, received £444 15s per annum, or almost 20% of de Vere’s net yearly revenue, as her jointure.111 After Margery Golding’s death, he should have received the income from these lands. However, the Queen initiated a lawsuit claiming that she was entitled to the remainder of the revenue from Margery Golding’s jointure.112 Moreover, the surviving documents show that the Queen not only intended to take from her young ward the revenue from the lands which had constituted his late mother’s jointure,113 but also another £343 6s 5-1/4d in net yearly revenue from lands which he had inherited in tail after his father’s death.114 This latter sum appears to have consisted principally of the revenue from Colne Priory and the office of Lord Great Chamberlain.115

Of the lands held in reversion, yet another £130 16s 8d, or almost 6% of his inherited income, went to de Vere’s three paternal uncles and their wives during their lifetimes.

A further £333 18s 7d, or almost 15% of de Vere’s net yearly revenue, was sequestered for twenty years from the date of the 16th Earl’s death for payment of his debts, his legacies, and Katherine de Vere’s marriage portion. No figures survive for the 16th Earl’s debts, and it is therefore not known to what degree they constituted a charge against his estate, but the legacies left by the 16th Earl total £3745 17s 1d, or 56% of the total net revenue of £6678 11s 8d which would have been generated over the twenty-year period from the lands set aside for payment of the 16th Earl’s debts and legacies.116

De Vere’s income over his lifetime can thus be summarized as follows. During his wardship, 30% of his net yearly revenue of £2250 went to the Queen as her “thirds,” and from her to Sir Robert Dudley under the grant of 22 October 1563; another 20% went to his mother until her death on 2 December 1568 and was thereafter sequestered by the Queen until the matter was litigated in 1571; another 6% went to his three paternal uncles and their wives during their lifetimes; and a further 15% was set aside for twenty years for payment of the 16th Earl’s debts and performance of his will. Thus, during the nine years of de Vere’s minority, 71% of his net yearly revenue went to others, while only £643 5s 1-1/4d,117 or 29%, went to the Court of Wards, whose officers expended it for his maintenance, and almost certainly for the maintenance of his sister Mary de Vere as well during her minority.118

When de Vere was granted license to enter on his lands on 30 May 1572, a year after reaching the age of majority, his financial situation improved considerably. In addition to the 29% which he had received during his minority, he was now eligible to receive the 30% which had gone to the Queen, and from her to Sir Robert Dudley during his wardship, as well as the 20% which represented his late mother’s jointure, although it seems the Queen kept the latter from him until after she had litigated the matter in 1571. Thus, in 1572, after he was granted license to enter on his lands and began receiving the revenue from the lands which had constituted his mother’s jointure, de Vere would have received the largest amount of income which ever came to him in any single year from his inherited lands and offices, i.e., 79% of the total £2250, or approximately £1777. In addition, it appears from the license that he would have received in that year the arrears owing for the year which had passed since he had come of age:

And further of our more abundant grace we have given & granted….to the forenamed Edward, now Earl of Oxenford, all & singular the issues, rents, profits….of all and singular the foresaid honours, castles lordships, manors, lands . . . hitherto and thereafter resulting….to us….from the time at which the foresaid Edward, Earl of Oxenford, attained his full age of twenty-one years….

It was not until the deaths of his paternal uncles and their wives119 that he was eligible to receive the additional 6% which went to them during their lifetimes, and it was not until after the expiration of the twenty-year term in 1583120 that he was eligible to receive the additional 15% from the lands set aside for performance of his father’s will. However, by the time de Vere was finally entitled to received this additional revenue in the 1580s, he had already sold off most of his lands, and the income stream from his lands had therefore shrunk dramatically. It is thus apparent that the largest amount of income de Vere would ever have received in any single year from his inherited lands and offices was the 79%, or approximately £1777 plus arrears which he would likely have received in 1572. From 1573 on, his income stream diminished with each passing year as he sold off his lands. The first major sale occurred as early as 1573, when he sold his mansion at London Stone to Sir Ambrose Nicholas.121 The high water mark of £1777 plus arrears in 1572 is thus far short of the imaginary net yearly revenue of £3500 or more with which modern historians have erroneously credited him, and which they have then vilified him for wasting in profligacy.122

Moreover, even in 1572, the windfall year in which de Vere would have received 79% of the total annual value of his inherited lands and offices, or approximately £1777 plus arrears, most of the money was already spoken for, and there was no possibility of his wasting it in profligate expenses even had he wished to. Every year there were the ongoing charges of maintaining his lands, as well as the expenses attendant on the establishment of a household for himself and his wife, Anne Cecil. Moreover, until his sister, Mary de Vere married in 1578,123 he would have been responsible for her maintenance, which in 1573 was stated to be £100 a year.124 In addition, there was the ongoing repayment of his debts, which on 30 January 1575 amounted to approximately £9096 10s 8-1/2d.125 Some of these debts had been incurred by the ruinous expenses attendant on living the life of a courtier,126 and £3457 of the total amount consisted of his debt to the Queen herself in the Court of Wards, discussed in greater detail below.

In 1573, de Vere assigned £400-£500 for the payment of his debts,127 but he was not able to meet those obligations without selling land. Even after he had begun to resort to selling his lands, his failure to pay off his debts was the subject of public complaints from the Queen, his sister,128 and others. In a letter to Lord Burghley from Siena on 3 January 1576, he wrote:

My Lord, I am sorry to hear how hard my fortune is in England, as I perceive by your Lordship’s letters. But knowing how vain a thing it is to linger a necessary mischief, to know the worst of myself & to let your Lordship understand wherein I would use your honourable friendship, in short, I have thus determined, that whereas I understand the greatness of my debt and greediness of my creditors grows so dishonourable to me and troublesome unto your Lordship that that land of mine which in Cornwall I have appointed to be sold (according to that first order for mine expenses in this travel) be gone through withal, and to stop my creditors’ exclamations (or rather defamations I may call them), I shall desire your Lordship, by the virtue of this letter (which doth not err, as I take it, from any former purpose, which was that always upon my letter to authorize your Lordship to sell any portion of my land), that you will sell one hundred pound a year more of my land where your Lordship shall think fittest, to disburden me of my debts to her Majesty, my sister, or elsewhere I am exclaimed upon. Likewise, most earnestly I shall desire your Lordship to look into the lands of my father’s will which, my sister being paid and the time expired, I take is to come into my hands.129

The Queen’s public complaints in late 1575 and early 1576 that de Vere had failed to pay his debt to her in the Court of Wards must have been particularly galling to him, considering the enormous financial benefit which she had already reaped from his wardship, discussed more fully below. In summary, de Vere’s inherited annual income, relatively small as it was, diminished as it was by wardship, and encumbered as it was by debt, was clearly insufficient for him to maintain the lifestyle of a courtier for any prolonged period of time. So long as he remained at court, it was inevitable that he would go further into debt, and would be required to sell his lands to meet his living expenses.

IV. The Queen’s mismanagement of de Vere’s wardship

While misinformed commentators have attempted to explain de Vere’s financial downfall by crediting him with a vastly inflated inherited annual income which he did not possess, the ultimate cause of his financial downfall has gone unnoticed. It was the Queen’s mismanagement of de Vere’s wardship and the stranglehold which she held over his finances during his entire lifetime which led inevitably to his financial ruin. Before dealing with specific examples of the Queen’s mismanagement of de Vere’s wardship, it is necessary to consider how the assets which fell into the Queen’s hands through prerogative wardship were valued. Hurstfield explains that there were two separate items to be sold, the wardship and the lease of the ward’s lands, and the first step in arriving at a sale price for each of them was to determine the net yearly revenue130 from all the lands held by the deceased tenant in chief at his death. To this end, an inquisition post mortem was taken, and the feodaries in the various counties in which the lands were held conducted surveys.131 That done, two separate bargains were struck:

The first was the sale of the wardship and what that involved: custody of the child and the right to marriage. This the guardian bought outright and the patent conferring the grant clearly stated that this royal grant belonged to him, his executors and assigns. . . .

But, apart from the wardship, there were also the ward’s lands to be leased away, and these called for a quite separate transaction. The crown had resumed possession of the land, because the ward could not render military service, and held it until the ward was of age and in a position both to serve the king and therefore reclaim his land, that is to say, to sue livery. Meanwhile the crown could let the land at an annual rent for the period of the minority. Sometimes it went to the purchaser of the wardship, sometimes to a complete stranger. There was first a ‘fine’ or premium to be paid by the lessee, usually half the rent of the lands, and there was the annual rental for the property. But how should the master assess the price of the wardship? For that, too, he had to use as his basis the value of the inherited lands.132

With respect to the sale price of a wardship (i.e., the physical custody and guardianship of the ward, and the right to offer him a marriage), Hurstfield concludes that the formula generally followed by Lord Burghley as Master was that “the selling price followed fairly closely upon the annual value of the lands.”133 Hurstfield cites several cases from the “fourth year of Elizabeth’s reign”134 as evidence that this formula was then in use. Since the fourth year of Elizabeth’s reign was the year in which he became a ward, it thus seems highly probable that his wardship was valued by the Court of Wards at £2250, a sum equal to the net yearly revenue from his lands.

With respect to the sale price for the lease of a ward’s lands during his minority, Hurstfield concludes that the price generally charged was an annual rent equal to the net yearly revenue of one-third of the lands, plus an initial premium of half that amount. Applying that formula, the Queen was entitled to one-third of £2250, or £750 per year for each of the nine years of his wardship (£6750) plus an initial premium of half the annual rental value (£375), for a total of £7125.

The purchaser of a wardship often hoped to marry a ward to his daughter, thus bringing the ward’s inheritance into the family, or if not, to make a profit by selling the ward’s marriage to a third party. But how did the lessee of a ward’s lands expect to make a profit if he was required to pay the Queen an annual rent equal to the net yearly revenue of the lands plus an initial premium? Hurstfield attempts to answer this question by claiming that the rents in the feodaries’ surveys were artificially low, with the implication that the lessee could raise them:

This rental was easy enough to assess: it was the same as the figure provided by the feodary’s survey. Low it undoubtedly was (and that is where the lessee gained enormously), but it was as high as the current attitudes and procedures would allow.

There is, however, no evidence for Hurstfield’s claim that the tenant in chief’s lands were undervalued in the feodaries’ surveys. Hurstfield also says that the Court of Wards relied on the feodaries’ surveys because of their accuracy, while Bell says that in many cases the rental values in the feodaries’ surveys were actually higher than those found in the inquisitions post mortem.135

The answer to the question of how a lessee could make a profit from a ward’s lands leased to him by the Queen, or whether indeed the lessee did make a profit, lies in distinguishing among the attitudes toward profit on the part of three very different types of lessees. In some cases, the ward’s mother or another family member purchased both the wardship and the lease of the lands, and at great personal hardship simply gave up the revenue from one-third of the family’s lands to the Queen during the wardship, paying her the annual rental value of the lands as assessed by the feodary’s survey without, of course, making a profit of any kind. In other cases, both the wardship and the lease of the lands were purchased by someone with a daughter to whom he hoped to marry his ward. In such a case, the purchaser would also pay the Queen the annual rental value of the lands as assessed by the feodary’s survey throughout the wardship without making a profit because eventually the lands would end up in the family through the marriage. The third type of purchaser was one who had every intention of making a profit, and who would not hesitate to rack the tenants by raising rents, to neglect the maintenance of buildings, to sell off woods or to otherwise despoil the lands. It was not unusual for a ward’s lands to be ruined during his wardship if they fell into the hands of this type of purchaser. As Hurstfield says:

The lease of the ward’s lands could, by the nature of things, be only of limited duration. His death, or his coming of age, would terminate it. Here were all the temptations to a lessee to force the land to yield a quick return…Sir Thomas Smith, who quoted some frank comments about the education of wards, had even sharper words to say about the treatment of their estates. Their inheritance, he tells us, when they came of age, consisted of ‘woods decayed, old houses, stock wasted, land ploughed to the bare’.136

The Queen put the core de Vere lands into the hands of her favorite Dudley, who by all accounts was precisely this third type of purchaser. Although there is little direct evidence of his stewardship of the core de Vere lands, the blistering criticism in Leicester’s Commonwealth concerning the practices by which he stripped lands of their assets and left them worthless137 renders it likely that the core de Vere lands were badly mismanaged during his minority, and that the officers put in place by Dudley served his interests, not those of the young de Vere. A particularly revealing example of Dudley’s rapaciousness which also illuminates his attitude towards the de Vere family is afforded by his callous treatment of the 16th Earl’s widow, Margery Golding, when at Michaelmas 1563 he denied her rent corn for her household from the tenants of Colne Priory.138

With the value to the Queen of de Vere’s wardship established at £2250, and the value to her of the lease of his lands during his minority established at £7125, we can now turn to several specific examples of the Queen’s mismanagement of the wardship:

- Her failure to properly determine the legal basis of her claim to Edward de Vere’s wardship;

- Her seizure of more than the one-third of the revenue from de Vere’s lands to which she was legally entitled under the Statute of Wills;

- Her grant of the core de Vere lands to her favourite, Sir Robert Dudley, in order to ‘benefit’ him;

- Her lawsuits against de Vere for the remainder of the revenue from the lands which had constituted his mother’s jointure, and for the revenue during his entire wardship from lands and offices which had descended to him in tail;

- Her fine of £2000 against de Vere in the Court of Wards for his wardship;

- Her failure to follow the clause in the 16th Earl’s will which would have ensured that de Vere had adequate funds available to pay the fine for his livery when he came of age;

- Her failure to further the marriage contract for de Vere which had been entered into by the 16th Earl and the 3rd Earl of Huntingdon;

- Her unfulfilled promises to de Vere in his youth which induced him to spend money which he could ill afford to spend.

1. The Queen’s failure to properly determine the legal basis of her claim to Edward de Vere’s wardship

The legal basis of the Queen’s right to de Vere’s wardship was not a cut and dried matter. Had Somerset died holding legal title to the 16th Earl’s lands comprised in the fine of 10 February 1548 as a tenant in chief of the Crown by knight service? If so, was it possible for the private Act of Parliament of 23 January 1552 to have transferred those tenures back to the 16th Earl retroactively after Somerset’s death simply by deeming the 1548 fine to the 16th Earl’s use? Was Sir James Dyer correct in holding in 1571 that de Vere had taken the lands comprised in the fine as a purchaser and not by descent? If so, how can Dyer’s judgment be reconciled with statements in the inquisition post mortem of 18 January 1563 which find that the 16th Earl held those same lands as a tenant in chief of the Crown by knight service?139 What was the effect of the saving clause in the private Act of Parliament of 23 January 1552? Did it preserve the Crown’s right to wardship, or was the Crown’s right to wardship only preserved if the essential precondition of wardship had been met, namely that the 16th Earl had died seised in his demesne as of fee of at least one acre of land held from the Crown in chief by knight service? What legal effect had the 16th Earl’s attempt to recreate the ancient entails and his appointment of trustees holding his lands to his use in his indenture of 2 June 1562 had on the tenures by which he held his lands at his death? It seems clear that these complex legal issues should have been carefully investigated, and perhaps even litigated, before the Queen seized de Vere’s person and lands into wardship, but they were not. De Vere’s wardship was unique. Unlike any other wardship, it was ostensibly governed by the terms of the private Act of Parliament of 23 January 1552, and not merely by the rights of prerogative wardship and the Statute of Wills. It was thus fraught from the outset with potential legal problems which were never properly resolved.140

As the Queen herself did not take the initiative in carefully investigating her legal right to de Vere’s wardship, it was up to the three trustees appointed under the 16th Earl’s indenture of 2 June 1562 to urge her to do so. As both the 16th Earl’s trustee under the indenture and a supervisor of his will, it would seem that Dudley had an even greater responsibility to vigorously protect de Vere’s interests than the other two trustees. However, instead of insisting that the legal issues concerning the Queen’s right to de Vere’s wardship be properly resolved, Dudley immediately, with the Queen’s blessing, assumed de facto control of the core de Vere lands in East Anglia.141 His two co-trustees under the indenture, the 16th Earl’s nephew, the Duke of Norfolk, and his brother-in-law, Sir Thomas Golding, also abrogated their responsibilities as trustees and passively acquiesced in the Queen’s assertion of wardship rights and Dudley’s assumption of de facto control over the core de Vere lands. Sir Thomas Golding can perhaps be partly excused for not taking the lead when his co-trustees, Norfolk, one of the highest-ranking members of the nobility, and Dudley, the Queen’s favorite, had failed to do so. But Norfolk’s neglect of his late uncle’s interests, and his failure to protect the rights of his young first cousin, against the Queen and Dudley are more difficult to explain or condone.

In short, the three co-trustees apparently did nothing to urge that the legal issues be properly investigated before the Queen asserted wardship rights over de Vere, and the Queen herself simply ignored the legal complexities. De Vere became the Queen’s ward on 3 August 1562, and the way was paved for a mismanagement of his wardship by the Queen which led to his eventual financial ruin.

2. The Queen’s seizure of more than the one-third of the revenue from de Vere’s lands to which she was legally entitled under the Statute of Wills

The Statute of Wills of 1540 provided much-needed clarity on the issue of the King’s prerogative rights when a tenant in chief died holding land by knight service:

And it is further enacted by the authority aforesaid, That all and singular person and persons having any manors, lands, tenements or hereditaments of estate of inheritance holden of the King’s highness in chief by knights service, or of the nature of knights service in chief, from the said twentieth day of July shall have full power and authority, by his last will, by writing, or otherwise by any act or acts lawfully executed in his life, to give, dispose, will or assign two parts of the same manors, lands, tenements, or hereditaments in three parts to be divided, (2) or else as much of the said manors, lands, tenements, or hereditaments, as shall extend or amount to the yearly value of two parts of the same, in three parts to be divided, in certainty and by special divisions, as it may be known in severalty, (3) to and for the advancement of his wife, preferment of his children, and payment of his debts, or otherwise at his will and pleasure; any law, statute, custom or other thing to the contrary thereof notwithstanding;

Saving and reserving to the King our sovereign lord, the custody, wardship and primer seisin, or any of them, as the case shall require, of as much of the same manor, lands, tenements or hereditaments, as shall amount and extend to the full and clear yearly value of the third part thereof, without any diminution, dower, fraud, covin, charge or abridgment of any of the same third part, or of the full profits thereof;

Saving also and reserving to the King our said sovereign lord, all fines for alienations of all such manors, lands, tenements and hereditaments, holden of the King by knights service in chief, whereof there shall be any alteration of freehold or inheritance made by will or otherwise, as is abovesaid.142

The effect of this legislation was felt in every corner of the realm. Henry VII had been assiduous in searching out his tenants in chief, and his son and heir, Henry VIII, had granted out much additional land by knight service. It was now clear that any tenant in chief who held so much as an acre of land by knight service could devise two-thirds of his lands by will,143 but on his death the remaining one-third would be subject to the King’s prerogative rights of custody, wardship and primer seisin. If the heir were of full age, the King would take and retain seisin of one-third of his lands until the heir had sued livery, performed homage, and paid a relief144 equivalent to the net yearly revenue from all his inherited lands for the first year. If the heir were underage, the King would seize the physical custody and guardianship of the heir, which included the right to his marriage, and would take the net yearly revenue from one-third of the ward’s lands during his minority. The King would retain both the person of the heir and the net yearly revenue from one-third of his lands until the heir came of age and sued livery, performed homage, and paid a relief equivalent to half the net yearly revenue from all his inherited lands.

The Statute of Wills thus imposed an inheritance tax on the heir of every tenant in chief in the realm, whether the heir was of full age or underage.145 The burden on the underage heir was, of course, by far the more onerous since it involved the guardianship and physical custody of his person, the right to his marriage, and the net yearly revenue from one-third of his lands during his entire minority, as well as the requirement that he sue livery and pay a relief when he came of age, just as an heir of full age had to do.

Such a system had to be imposed on every heir in the realm whose father had died holding as a tenant in chief by knight service, whether the heir was of full age or not, generated a considerable bureaucracy. More importantly, it generated a very large number of underage wards. The Crown obviously could not keep all these underage wards or their lands in its own hands, and in almost every case the underage heir and his lands were disposed of by sale. Hurstfield describes the stark realities of Tudor wardship: