Fake Truth and “Professional Shakespeare Scholarship”

by Steven Steinburg

April 4, 2018

[P]rofessional Shakespeare scholars — those whose job it is to study, write, and teach about Shakespeare — generally find Oxfordian claims to be groundless, often not even worth discussing.[1]

— David Kathman

The Example of William Shakspere’s Mythical Grammar School

The Example of William Shakspere’s Mythical Grammar School

One of the most astounding and troubling things about Shakespearean-Elizabethan scholarship is the institutional acceptance of speculation as virtual fact, what I call fake truth.[2] This is a major part of a systemic failure, but it is a relatively recent development embodied in what have become the two central presumptive truths of modern Shakespearean scholarship. The first was Edmund Chambers’ standard chronology published in 1930.[3] The second was T.W. Baldwin’s claims about the Stratford grammar school and Elizabethan grammar school culture, published in 1944. Here, I will speak to the latter.

Baldwin’s two-volume magnum opus bore the title, William Shakspere’s Smalle Latine and Lesse Greeke. Here are his principal claims:

- Most important of all, if Shakspere had this grammar school training, he had the only formal literary training provided by society in his day. University training was professional, with literary training only incidental and subsidiary…[4]

- Thus the grammar school provided an intensive and detailed literary training based upon the best Latin authors.[5]

- If William Shakspere had the grammar school training of his day—or its equivalent—he had as good a formal literary training as had any of his contemporaries…[6]

- Foremost of these is the fact that the sixteenth century grammar school curriculum was highly organized and had by the middle of the century been standardized into essential uniformity… [7]

- At least, no miracles are required to account for such knowledge and techniques from the classics as he [Shake-speare] exhibits…[the] Stratford grammar school will furnish all that is required. The miracle lies elsewhere; it is the world-old miracle of genius…[8]

Baldwin’s conclusions were, arguably, the greatest gift ever handed to the champions of the improbable Stratfordian tradition. In my first book, I Come To Bury Shakspere (2011), I deconstructed Baldwin’s principal claims point for point. Here I abbreviate the arguments from the soon to be released 3rd edition. The point I wish to begin with is the question that no one bothers to ask: What is meant by “curriculum?”

The word curriculum simply defined means ‘the aggregate of subjects that are taught’. The primary purpose of the Elizabethan grammar school curriculum was to teach Latin. Historically, the teaching objective was competency in reading, writing, and speaking Latin, and sometimes Greek. The secondary purpose imposed by King Henry 8th was Reformation indoctrination. The statutes of various schools show that the curriculum often included rhetoric and sometimes logic. However, Baldwin claimed that the curriculum included ‘literary training’ with a list of specific literary texts that were to be studied in-depth as part of a ‘national standard curriculum’. Baldwin refers to “essential uniformity” and he repeats the words uniformity and essential uniformity over and over. Though it went unnoticed for some seventy years, Baldwin’s claim of ‘essential uniformity’ in literary training stands in gross conflict with the historical evidence and common sense. Belief in this ‘standard curriculum’ including literary texts has become a cornerstone of the modern Stratfordian belief. The following from Baldwin should be read carefully (underline added):

In the next stage, the system which by 1530 has been evolved at Eton is hardened into uniformity, and spreads to other schools. We have already seen how by 1529 Wolsey and the Convocation of Canterbury were seeking uniformity in teaching grammar, that meaning necessarily essential uniformity of the total curriculum. To harden the grammar into uniformity was to go far toward hardening the whole curriculum. So, when the whole cathedral machinery was being reorganized in the ’forties, the cathedral schools were provided with uniform regulations. The curricula are not included, but in two cases were attached. It is significant that these two are essentially identical and represent further clarification of the Eton system as it was in 1530.[9]

If we take curriculum to mean the teaching of Latin, to include the basic grammatical instructions to be used and the basic methods of instruction and class organization, this is true but misleading. Necessity and common sense had produced a large degree of uniformity in the Tudor-Elizabethan grammar school curriculum. By Royal Injunction King Henry required that Lily’s Grammar would be used to the exclusion of other ‘grammars’. This grammar textbook came to be referred to as The King’s Grammar, and later, under Elizabeth, The Queen’s Grammar.

Practically speaking, the Eton curriculum did become the model for most English grammar schools and we often find Eton is cited in the statutes for other schools usually with reference to ‘grammar’. But again, that uniformity was not the big deal that Baldwin would have us believe. As already mentioned, a significant degree of uniformity of methods and organization had occurred naturally, or inevitably, but, apart from the mandated grammar text, other elements of curriculum were never standardized by law, least of all the literary texts that were used.

[pullquote]Specific literary texts that were used in the teaching of Latin or Greek were never standardized, not even into the next century, or even into the 20th century.[/pullquote]Here is the essential point. Specific literary texts that were used in the teaching of Latin or Greek were never standardized, not even into the next century, or even into the 20th century. Selecting literary texts for teaching Latin and Greek was the prerogative of local schoolmasters and administrators, and this makes sense for several reasons. First of all, except to exclude undesirable texts, the central government had no reason to care about which literary texts were being used. Second, literary training per se was never part of the grammar school curriculum or the grammar school objective. And third, there was never any uniformity in the texts that were available.

Grammar schools were locally funded and had to purchase their own books. In some cases the books may have been supplied by the schoolmaster. It is possible that elite schools had as many as 20-30 different books, but what would the point have been when a handful of texts would have been perfectly adequate? Some grammar schools (as we shall see), appear to have had less than six literary texts. The only book that is actually recorded to have been available at the Stratford grammar school was Cooper’s Dictionary, ‘kept on a chain’. Baldwin quips:

…a few years before William Shakspere got there; and it can do no harm for us to hope that this dictionary and many other works of Paul’s list were there in chains awaiting him.[10]

Here again are two of Baldwin’s most important claims:

- Thus the grammar school provided an intensive and detailed literary training based upon the best Latin authors.[11]

- Most important of all, if Shakspere had this grammar school training, he had the only formal literary training provided by society in his day. University training was professional, with literary training only incidental and subsidiary…[12]

When Baldwin published these false claims they were simply his own false claims. But those claims were immediately accepted without peer review and without a word of objection and within a few short years were institutionalized into a grand fake truth that continued to blossom in the creative hands of subsequent Stratfordian scholars. Basically, all of Baldwin’s principal claims about literary training in the grammar schools are patently false. Period! Pardon the redundancy, but to be clear: 1) grammar schools had no literary training objective; 2) literary training was a by-product—grammar schools definitely did not provide “detailed literary training”; 3) the universities did provide literary training (it is absurd to claim otherwise). But according to Baldwin, for Shakespeare’s purposes:

…the Stratford grammar school will furnish all that is required.

Stratfordian scholars were all too eager to accept Baldwin’s conclusions in what was arguably the single most important advance in Stratfordian scholarship of all time. I have not been able to discover any evidence of peer review. All that I have discovered is gullible applause. And though Baldwin tried not to state the claim explicitly, the implicit idea that he succeeded in passing along was that there was a standardized curriculum used by all Elizabethan grammar schools that included a comprehensive uniform collection of classical literary titles. Thus arose, in 1944, the most important fake truth in the history of Stratfordian scholarship, even more important than the standard chronology.

We come to 2013. In the Wells-Edmondson compilation, Shakespeare Beyond Doubt, we find an article by Carol Chillington Rutter[13] with the title, ‘Shakespeare and School’. Speaking of the Royal Charter of the Stratford grammar school, she says:

It established from 1553 a ‘free grammar school’ in Stratford on Avon, and with it, what by then had settled into the de facto national curriculum…That curriculum taught Latin grammar, literature—the ‘polite literature’ alluded to in the Royal Charter…[14]

To the contrary, there was definitively no ‘de facto national curriculum’ by 1553 or any time during that century that included the teaching of ‘literature’, ‘polite’ or otherwise. How can this not be known to an ostensible authority on the subject of Shakspere’s schooling and Elizabethan grammar schools? Rutter goes on to say:

As far as [Shakspere’s] literary equipment goes, it was T.W. Baldwin’s exhaustive research back in 1944 in the two thick volumes of Small Latine & Lesse Greeke that comprehensively demolished the notion that Shakespeare would have needed a university education…The majority of them [Shakespeare’s works] derive, Baldwin found, ‘from the standard books and curriculum of the Elizabeth grammar school’.[15]

In volume 2 of Baldwin’s famous work, he identified the classical sources that Shakespeare drew upon. For the purpose of this discussion we need not debate the accuracy of that part of Baldwin’s claims. Baldwin theorized that those sources (those literary texts) must have been part of Shakspere’s grammar school training. In other words, Shakespeare’s sources, as identified by Baldwin, became the means of defining the grammar school curriculum for all of Elizabethan England.

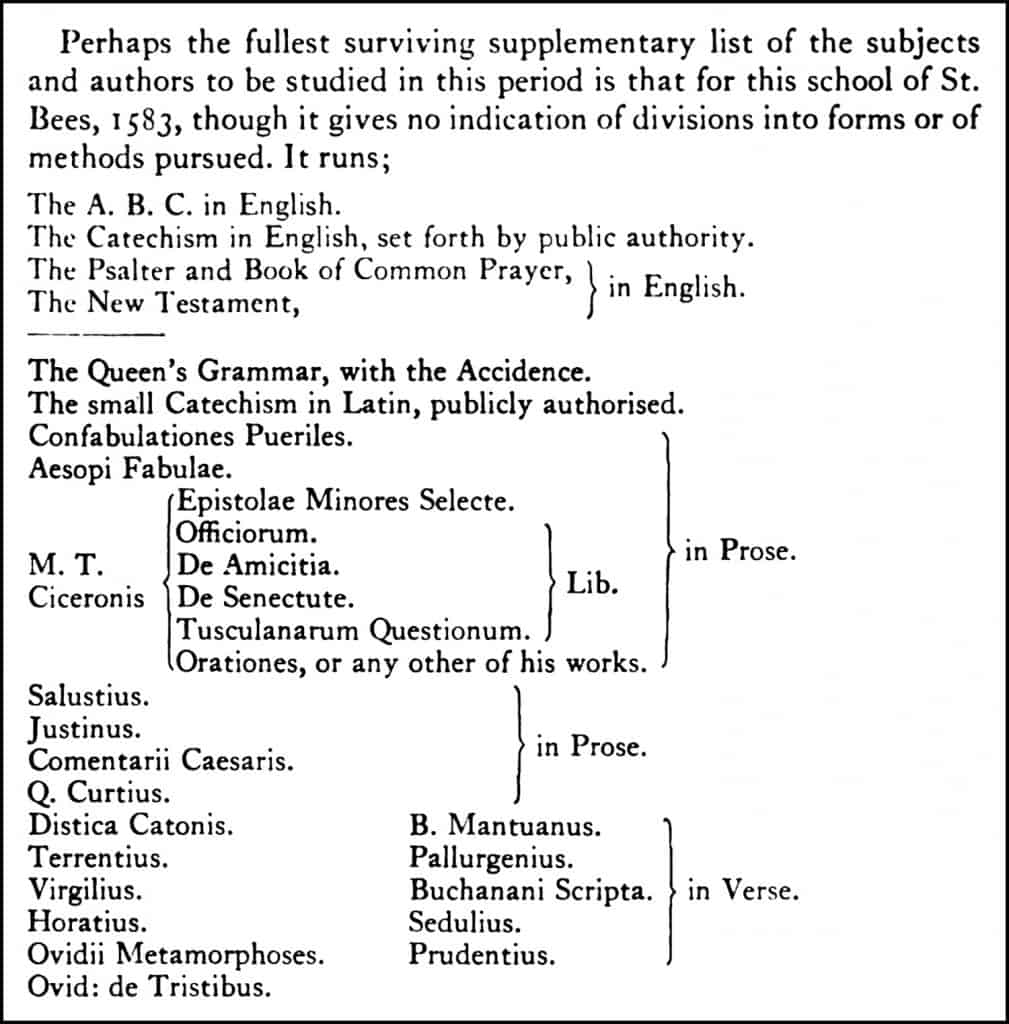

More than seventy years have passed since Baldwin palmed off his conclusions on a gullible academy and no one, as best I can determine, has raised a whisper of doubt or criticism about claims that in large part are ridiculous on their face. Why should Rutter not accept what has come to be regarded as fact by hundreds of her peers? The question is rhetorical. But let us get down to proverbial brass tacks. What literary texts (books) were used in Elizabethan grammar schools? Baldwin provides a list from St. Bees which he suggests was representative. The following is snipped from Baldwin’s text (pp.432-3). Baldwin prefaces the list saying:

Consider carefully Baldwin’s wording, “supplementary list of subjects and authors to be studied”. This is both deceptive and revealing. First, if this is a ‘supplementary list’, where are the primary lists? Over and over Baldwin uses the words ‘uniformity’ and ‘essential uniformity’ to describe the ‘curriculum’ or ‘curricula’ across England. If there are lists why doesn’t Baldwin share those with us? And if there aren’t any lists, where is he getting his information? Actually, there are a couple of lists that Baldwin declined to share with us because they flatly refute his basic argument, as we shall see.

Second, Baldwin’s statement reveals, indirectly, that there were no ‘primary lists’. Again, if there were, there would be no need of resorting to a ‘supplementary’ list. The statutes of individual grammar schools (as we find in Baldwin’s two volumes) sometimes mention literary texts that could or should be used. But these varied greatly from school to school. The underlying concern was texts that should not be used because they were counter-Reformation or because they contained too much erotica. There is nothing in the St. Bees list, or the accompanying statutes, that indicates that all of those texts must be studied and or that any of them must be studied comprehensively. Such lists served as a guide to suitable texts to facilitate the teaching of Latin or Greek. Teachers could pick and choose from such lists, subject to which texts were actually available, and it is evident that what was available varied greatly from school to school.

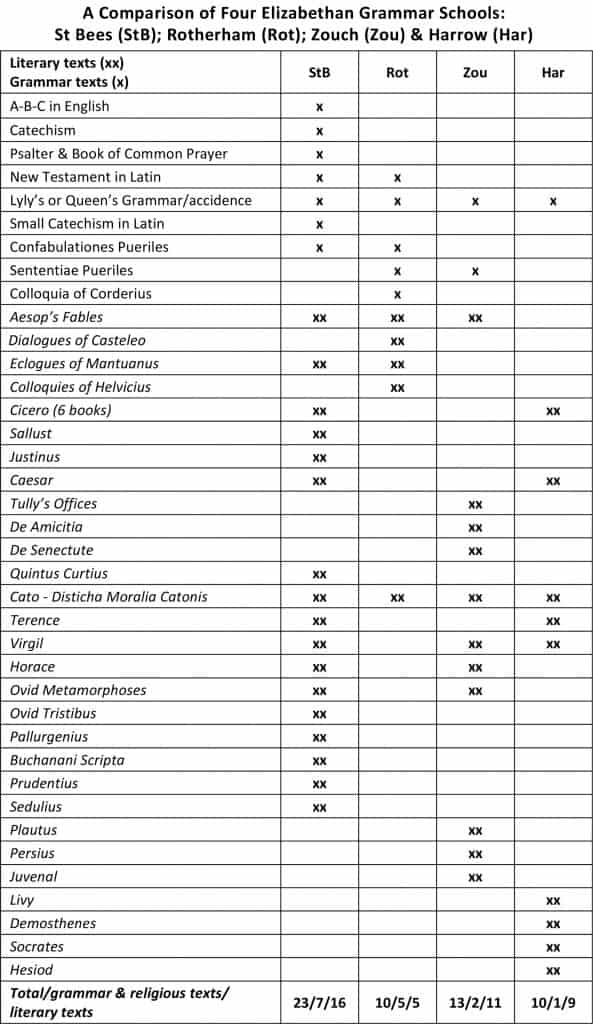

Third (pardon the redundancy), if, as Baldwin would have us believe, there was ‘essential uniformity’ in these ‘lists’, where are the lists? How can it be that so many of the statutes have survived but there is not so much as a single list of literary texts actually prescribed for in-depth study? Moreover, there is, as best I can determine (inferring from the wording of the statutes), no case where a school statute mandated in-depth study of any literary text. But, speaking of ‘lists’, what is truly interesting are the ‘supplementary lists’ that Baldwin does not share with us. In the following table taken from my first book,[16] is a comparison of the St. Bees list (as provided by Baldwin), with lists from three other grammar schools as provided by Plimpton.[17] I think the reader will find the comparison eye-opening.

‘Book Lists’ From Four Grammar Schools—A Comparison of Four Elizabethan Grammar Schools[18]: St Bees (StB); Rotherham[19] (Rot); Zouch[20] (Zou); Harrow[21] (Har)

We need look no further than Hoole’s list[22] for Rotherham to see that Baldwin’s primary assertion is utterly false. The Rotherham list has five grammatical texts and only five literary texts. Combining the titles of Rotherham, Harrow and Zouch, there are 12 literary titles that do not appear on the St. Bees list. Moreover, in spite of the alleged ‘essential uniformity’ the only literary text that is common to all four schools is Cato.

So, what about Stratford? Baldwin says the Stratford grammar school was “in the lowest possible class”. Rotherham was a much larger and more significant town than Stratford, but there are only 5 literary texts listed for that grammar school. Until 1547, when the college of Rotherham was dissolved by order of Edward 6th, Rotherham was a college town (as it is today). Without assigning a ‘class’ to the Rotherham grammar school, based merely on the wealth of the families it served, it was almost certainly better resourced than the school at Stratford. Conversely, there is absolutely no reason to suppose that the Stratford grammar school would have been better equipped than Rotherham or Zouch or Harrows. Even allowing that the literary titles available at those three schools were taught comprehensively, that could hardly be viewed as advanced ‘literary training’ or, more to the point, “all that is required” for Shakespeare, as Baldwin claims. Unaware of the essential facts, Rutter says:

On every page, in every speech, every line Shakespeare wrote we see the mental imprint of the grammar school.[23]

This is complete nonsense. Perhaps Rutter would like to argue that Zouch and Harrow and Rotherham were exceptions, and that Stratford was somehow superior even to St. Bees, or that Plimpton’s lists are inaccurate. Otherwise she will need to drastically rethink the “mental imprint” William Shakspere is likely to have taken from the Stratford grammar school, assuming he attended at all, which is by no means certain. Ridiculously, Rutter goes on to say:

And if the education system that produced England’s greatest theologians, ambassadors, lawyers, physicians, moral philosophers and political thinkers, also produced its best playwrights…[24]

I would ask Rutter to name one of those ‘theologians, ambassadors, lawyers, physicians, moral philosophers and political thinkers’ and ‘playwrights’, other than Jonson, that did not have university training or the equivalent. Following in the absurdly speculative and logic-twisting footsteps of Baldwin, Rutter paints an even more Utopian picture of the Stratford grammar school as an enlightened educational institution with a comprehensive library of classical literary titles, offering in-depth training, not merely in Latin grammar, but in classical literature, imaginative writing, elocution, and even acting—all of this for boys between the ages seven to fourteen who were training to be clerks, clerics, and grocers. She says:

The cultivation of play in the grammar school—that place that Erasmus wanted to be ‘playful’, and Ascham (and Brinsley following him) called the ‘ludus literarius’—installed habits of ‘becoming the other’, of imagining other minds and voices: excellent preparation for a playwright.[25]

Erasmus and Ascham were the elite pedagogues of their era. These were the teachers of princes and princesses. There is little evidence that their enlightenment idealism filtered down to the average grammar school. In Rutter’s brief bio at the Warwick University website it says:

She has a special interest in early modern childhood and pedagogy (which aligns with her writing on teaching and learning in today’s university);[26]

Considering Rutter’s “special interest”, her ideas about Elizabethan pedagogy are all the more amazing. Rutter’s pedagogical world of Elizabethan grammar schools is a fantasy world quite apart from Elizabethan England or any place else on this planet. Elizabethan grammar schools were not noted for their ‘playfulness’. To the contrary, they were noted for unimaginative rote learning generously enforced with whipping, caning, slapping, punching, and other forms of physical punishment. I refer the reader to my book I Come To Bury Shakespeare.[27] Here, by way of example, is a quote from Stephen Greenblatt:

Everyone understood that Latin learning was inseparable from whipping.[28]

I say again, the purpose of Elizabethan grammar schools was to teach students to read, speak, and write competently in Latin and to indoctrinate them so they would be faithful Protestants. Underlying Rutter’s argument is the fantastical notion that young Will Shakspere had his eye on a career as an author-playwright and that his teachers encouraged and supported such bohemian ambitions. That is preposterous. At the time Shakspere was presumably studying at the Stratford grammar school there was not one example of a self-sufficient professional author in all of England. There is no evidence that grammar schools pursued such extravagant literary objectives even in the elite schools. Rutter, obviously, is infected by Baldwin’s naiveté and his imaginings about the ‘renaissance idea’ that had swooped over Elizabethan schooling, as Baldwin says (emphasis added):

The boys studied all the best Latin writers both in prose and verse and learned to model their own style upon them. Here is the fundamental formal literary training of the Renaissance. As fundamental literary training, can its basic technique as such be improved upon, if administered in the spirit of Erasmus? Was the English Renaissance such an unpremeditated accident after all? And if Shakspere had this training? [29]

The answer to the question Baldwin rhetorically asks is: there is no evidence that the state had a ‘premeditated’ goal or plan to create a ‘literary renaissance’. The state did promote (by policy, not by funding) literacy (in English and Latin) and the state’s motives for doing so were practical. No, the boys did not study “all” the best Latin authors and they didn’t study any of them comprehensively. If Stratfordian scholars had done their homework that would have been painfully clear back in 1944. I hope it is clear now. But Rutter says:

Learning by rote (word for word, ‘without book’), developing prodigious memories, students could for the rest of their lives, dip in the archive of the personal memory bank they’d stocked up as children for quotation, allusion, analogy, example—and not just of the classics but of the Bible, the Psalms and Book of Common Prayer.[30]

This is astounding in a number of ways. Rutter asserts that, by way of “rote learning” (“word for word, ‘without book’”), students would have somehow taken away an ‘archive’ memory of all those texts which were almost certainly not available. Obviously, one can’t have a memory of texts one wasn’t taught or had not had the opportunity to read, to which it needs to be pointed out that, with few exceptions, books were not placed in the hands of grammar school students. Typically the schoolmaster or usher (or sometimes an older student) would read a portion of text and the students would copy it down. And to this point we need to add that, at rural grammar schools, paper was in short supply. As Plimpton says:

Part of the slowness in teaching writing may have been caused by the cost of paper. Paper was not manufactured at all in England till the sixteenth century, and the cost of imported paper was heavy.[31]

Rutter makes the astounding claim that, in the process of “rote learning”, students developed “prodigious memories” and, “for the rest of their lives”, they could “dip” into this “archive” of their “personal memory bank”. Again, it is amazing to read statements such as these from a professor who is presumably a subject-matter expert and who has a “special interest in early modern childhood and pedagogy”. This level of ‘memory’ achievement, according to Rutter, was the rule not the exception.

From my personal experience I do not think that it is possible for an average student (such as myself for example) to develop a ‘prodigious memory’. Students attending common grammar schools were enrolled based on their eligibility under their father’s position or trade or profession. There was no qualitative process of selection that ensured that only boys with special cognitive abilities would be in those classrooms. Here are a few works that I consulted:

- ‘The Adolescent Brain – Learning Strategies & Teaching Tips’ http://spots.wustl.edu/SPOTS%20manual%20Final/SPOTS%20Manual%204%20Learning%20Strategies.pdf

- Richards, Regina. ‘Memory Strategies for Students: The Value of Strategies’. http://www.ldonline.org/article/5736/

- Terry, W. Scott. Learning and Memory: Basic Principles, Processes, and Procedures, 4th Edition.

- Yates, Frances. The Art of Memory, 1966.

In my admittedly cursory review of the available literature on ‘teaching, learning and memory’, and especially with respect to adolescents, I can find no mention of ‘prodigious memory development’ in classroom or group learning environments. It appears that ‘prodigious memory’ is particularly associated with ‘savant syndrome’. Among the strategies or techniques often cited for improved teaching/learning for normal students are small class size (six students or so) and creative interaction between teacher and students. Elizabethan grammar school classes typically had 50-55 students. If those classes were achieving ‘prodigious memory development’ in their students, surely modern pedagogues would want to know how they did it. Amazingly, as best I can determine, in spite of Shakspere’s famous achievements, not a single academic or expert has been curious enough to wonder seriously how this was accomplished. How can that be?

But let us put aside my inexpert opinion and let us disregard my layman’s foray into the expert literature on learning and memory. Rutter is a ‘professional Shakespeare scholar’. Who are the experts Rutter has consulted? Where are her citations for the expert literature that supports her incredible assertion about ‘prodigious memory development’ and ‘archive memory’? Where, in the history of pedagogy, are there examples of a particular curriculum, or particular teaching methodologies, converting normal students into prodigies? Since this is a subject of “special interest” to Rutter, and since she presumes to speak with authority on this topic, it goes without saying that she studied these matters. Isn’t that what ‘professional scholars’ do? Perhaps the absence of scholarly citations in Rutter’s essay will be dismissed with the argument that Shakespeare Beyond Doubt was aimed at the general public and not at specialists. In that case I ask to be directed to any scholarly discussions on the subject of the kind of ‘prodigious memory development’ Rutter refers to. But, seriously, we know that none will be forthcoming. I have one more quote from Rutter:

Most significantly, grammar school training, writes Robert Miola, ‘fostered certain habits of reading, thinking, and writing’ that would have spilled over into the students’ writing in English. They ‘acquired extraordinary sensitivity to language, especially in sound’.[32]

Robert Miola is a professor of English and Classics. He does not appear to be an expert on memory development or the subject of ‘acquired sensitivity to language, especially in sound’. In any case, there is zero factual evidence of this happening in the Stratford grammar school or in any other Elizabethan grammar school. Perhaps we should leave the door open a crack for the so-called cathedral grammar schools where the students doubled as choirboys. But, seriously, there is no contemporaneous evidence supporting the claim that Elizabethan grammar school students had “extraordinary sensitivity” to anything. That sort of detail was not passed along from that era. No, that is purely the product of Miola’s ‘expert’ imagination. Miola’s claim is substantively in the same class as the claims of Rutter and other Stratfordians who gush naively about the marvels of Elizabethan grammar training. This is the face of ‘professional Stratfordian scholarship’ today, and it is, to be specific, the language of ‘professional Shakespeare scholarship’.

Rutter’s essay is twelve pages long—twelve pages of fantasy, divorced from fact and reality, without meaningful supporting citations, but her essay is one of the two or three most essential parts of a larger argument that is allegedly ‘beyond doubt’. Her claims about Elizabethan grammar school effectiveness are, in a word, grandiose and baseless. Do real scholars speak in terms of utopian fabrications? Evidently so. This is ‘professional Shakespeare scholarship’—Fake truth, baked into their very special historical method.

BIO

Oxfordian Steven Steinburg is the author of I Come to Bury Shakspere.

Endnotes

[1] http://shakespeareauthorship.com/#1

[2] Not to be confused with fake news or alternative facts.

[3] Chambers, Edmund. William Shakespeare, A Study of Facts and Problems, 1930.

[4] Baldwin, T.W. William Shakspere’s Smalle Latine and Lesse Greeke, 1944. Vol. 2, page 662.

[5] Baldwin, Vol. 1, page 117.

[6] Baldwin, Vol. 2, page 663.

[7] Baldwin, Vol. 1, page 435.

[8] Baldwin, Vol. 2, page 663.

[9] Baldwin, Vol 1, page164.

[10] Baldwin, vol. 1, page 423.

[11] Baldwin, Vol. 1, page 117.

[12] Baldwin, Vol. 2, page 662.

[13] Professor Carol Chillington Rutter teaches at the Department of English and Comparative Literary Studies, University of Warwick. She is author of Enter the Body (2000).

[14] Paul Edmondson & Stanley Wells (eds.), Shakespeare Beyond Doubt: Evidence, Argument, Controversy (Cambridge: CUP, 2013). Page 134.

[15] Page 141.

[16] Steinburg, Steven. I Come To Bury Shakspere, 3rd revised edition (expected publication in April 2018).

[17] Plimpton, George A. The Education of Shakespeare, NY/London: Oxford UP, 1933.

[18] Except for the St. Bees data, information is taken from Plimpton, pages 45-6.

[19] Hoole’s list.

[20] Brinsley’s list. Ashby-de-la-Zouch Grammar School.

[21] John Lyon’s list.

[22] Dating to roughly 1630.

[23] Page 144.

[24] Page 144.

[25] Page 140.

[26] https://warwick.ac.uk/fac/arts/english/people/rutterprofcarol/

[27] Chapter 4.6, What Would Have Motivated Comprehensive Literary Training?

[28] Greenblatt, Stephen. Will in the World, page 26.

[29] Baldwin, Vol. 1, page 372.

[30] Pages 139-140.

[31] Plimpton, page 67.

[32] Page 139.

Membership dues cover only a fraction of our budget, including all our research, preservation and programming. Please support the SOF by making a gift today!

Blue Boar Tavern: Wassail Q&A

Tuesday Dec. 17, 8pm E / 5pm P

Sign up below for event invites!