Shelly Maycock

Originally published in Brief Chronicles First Folio Special Issue (2016), pages 5–30

“Thence comes it that my name receives a brand.”1

“It’s not enough to speak, but to speak true.”2

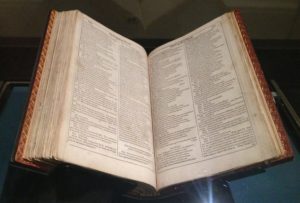

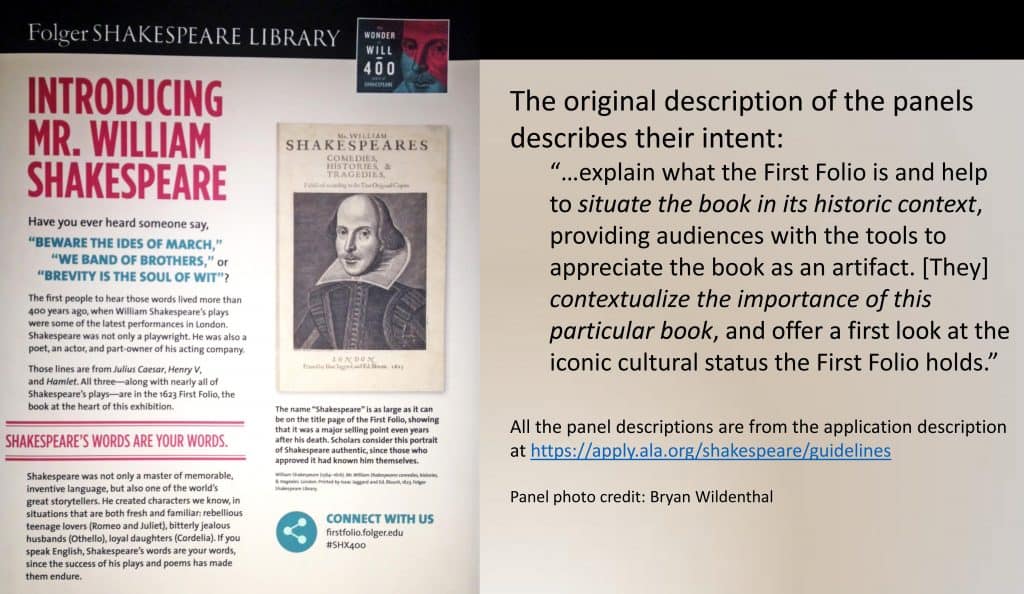

Select Folger Shakespeare Library First Folios (1623) are about to be displayed at libraries, universities and museums across the United States and its territories. As the exhibition is one of the major American contributions to international celebrations of the 400th anniversary of William Shakespeare of Stratford’s death, the Folger’s public event organizers have a wonderful opportunity to bolster their institution’s outreach and spread new insights about Shakespeare across the nation by offering United States citizens a glimpse of the library’s primary “icon.” Eighteen of the Folger’s eight-seven complete copies of the First Folio will be displayed for three weeks in each of the selected venues in 2016. Planned and orchestrated through the Folger Library’s combined partnership with the Cincinnati Museum Center (CMC) and the American Library Association (ALA), the tour, originally referred to (on the ALA site)3 as Shakespeare and His First Folio, is now known (in the application guidelines and press releases) as the First Folio! The Book that Gave Us Shakespeare. An array of formidable foundations has also contributed to the project. The tour is sponsored in part by a $500,000 grant from the National Endowment for the Humanities and also through the support of Vinton and Sigrid Cerf and Google.org.4

While the First Folio! tour is significant in itself as a Shakespearean cultural event, and the organizers seek to broaden the Folger’s influence, the library’s tour parameters suggest that they hope to do so by promoting a view of the Folio that ignores questions about its authorship and origins. Unfortunately, nothing in the pre-tour documents or the original application packet completed by the awarded venues indicates that Folger-approved experts will be informed about, or prepared to respond neutrally to, questions about Shakespeare’s authorship that often arise in relation to any study of the Folio’s historical and cultural context, creation and design. The Folger, consequently, seems poised to perpetuate its own longstanding policy of branding its iconic author’s works as forever unquestionably those of the inscrutable William Shakspere of Stratford-upon-Avon (1564-1616).

Exhibition sponsors insist that the tour is designed to be “thought provoking.” However, if past experience is any indication, serious questioning of the historical genesis of the book will be significantly limited by the Folger’s centralized planning. On the contrary, the worthy goal of hosting “thought-provoking” content may require local planners, exhibitors and scholars to use their own “out of the box” expertise to raise questions that are not covered by the Folger’s fastidious centralized planning. Their answers may benefit from those raised in this present Brief Chronicles special volume.

The exhibition themes of printing and cultural history highlight important and complex topics in Shakespeare scholarship unrelated to authorship per se, but the story of the author himself—who he was and how he made his art—are not stated themes of the exhibit, even though it is timed to coincide with the 400th anniversary of the alleged author’s death. Apparently the Folger missed the lesson of its own

1980 tour “Shakespeare: The Globe and the World.” John Russell, reviewing the tour for The New York Times, remarked that the tour did little to restore public confidence in the academic belief in the Stratford theory of authorship. Already, during the 1964 quadricentennial,

Fat biographies were thrust upon us, but they told us only what we already knew—that behind the three or four facts that were beaten into us at school, all is surmise. Behind the standard grammatical formulas – he “could have,” he “might have,” he “must have”and “he probably did”—a huge emptiness lurks.5

The vested traditionalists of the Shakespearean establishment seemingly put great pressure on the Folger staff to promote a rigid adherence to the orthodox theory of authorship, and therefore, to continually disregard the library’s fiduciary responsibility to maintain authentic neutrality and acknowledge the diversity of informed opinion. Few mainstream Shakespeare scholars feel compelled to acknowledge or consider alternative authorship theories. However, in the name of free inquiry, those who do seek to understand this issue, whether novice curiosity seekers, independent scholars or veteran academics, should neither be silenced nor insulted by uninformed, vague, or disrespectful answers. Such a response would reveal the speakers’ lack of preparation to consider the large questions raised by the Folio’s publication timing, design, and striking bibliographic features. These aspects have long raised serious doubts about the traditional theory of authorship.

The volume in which this essay appears should help exhibition librarians, curators, theater managers, speakers, and all manner of attendees address the gaps in the First Folio narrative in a more balanced fashion.

Under the circumstances set up by the First Folio tour directors, it may safely be predicted that some questioners who attend the exhibition know as much, or more, about certain critical topics than the Folger-approved speakers or curators. This volume of Brief Chronicles attempts to rectify this situation by placing in the hands of local organizers this “minority report” covering many of the issues omitted from the Folger’s publicity materials. Hopefully exhibitors, librarians, and tour event directors will avail themselves will use this resource to realize how truly “thought provoking” the First Folio really can be when it is released from the constricting assumptions behind the traditional authorship attribution. Ian Donaldson, author of the acclaimed 2011 Cambridge University Press biography of the First Folio’s actual managing editor, Ben Jonson, comments on the authorship question in discussing Jonson’s part in the publication of Shakespeare’s works as represented in the controversial fictional film, Anonymous. Donaldson argues that authorship cruxes involve “legitimate and provocative questions, which literary and historical scholars ignore at their own peril.”6

Such questions have long been the province of authorship doubters such as Gerald H. Rendall, who more than ninety years ago identified Jonson as the “most skilled agent of anonymity.”7 Unfortunately, many mainstream scholars misunderstand the value of this inquiry, and have read little if any of the published scholarship on authorship.8 Few can claim any specific or detailed knowledge of the most viable alternate candidate, the Earl of Oxford (1550-1604), let alone discuss the claims of other candidates such as Francis Bacon (1561-1626) or Christopher Marlowe (1564-1593) from an informed perspective.9 Yet an objective appraisal will show that Oxfordian studies have contributed much, and can contribute much more, to the lively appreciation and understanding of Shakespeare, as presented with the First Folio or early quarto texts, as well as early modern culture in general. Claims that such questioning “denies” or is “anti-Shakespeare” are regrettable expressions of prejudice, literally prejudgment, based not on evidence but belief.

Ironically, when more carefully evaluated, as the essays of this volume show, the Folio actually becomes one of the most profound elements of evidence against the orthodox view of authorship. Oxfordians are, therefore, gratified to support and participate in the Folger tour; for them it represents a unique opportunity to educate the public on their case. Unfortunately, such a line of inquiry, highlighting the central role the Folio has always played in generating questions about authorship, and suggesting the credibility of alternative scenarios, contradicts longstanding Folger policy of never admitting the actual evidence that supports alternative authorship scenarios.

There is much more to the Folio’s story than is generally recognized. Authorship skeptics raise inconvenient questions that challenge easy confidence in the received view of authorship that the Folger tour insists the public should uncritically accept as true. A striking case in point is that of the Folio’s patrons, Phillip Herbert, Earl of Montgomery (1584-1650) and his elder brother William Herbert, Earl of Pembroke (1580-1630), who are not mentioned in the Folger/ALA descriptions of the exhibition’s panels.10 Will the Folger’s hand-selected “experts” be prepared to point out that that Montgomery was the Earl of Oxford’s son-in-law, married to Lady Susan Vere, and that these two families were so closely related that Pembroke nearly married another de Vere daughter, Bridget? Will they even know who these men were, or that they were, at the time of the Folio, also close political allies of Oxford’s son, the 18th Earl, Henry de Vere, who throughout the printing of the Folio, was imprisoned in the tour of London for too vigorously contradicting the King’s plan to marry his son to the Spanish infanta? These patrons, named and celebrated on the next page after the Folio’s Droeshout image, which is a highlight in exhibition messages, were among the most direct living relatives of the 17th Earl of Oxford in 1623.11 If tour visitors inquire about the Folio “Brethren,” will the docents be prepared to explain that they were Oxford’s family members, closely associated with the Folio, and that these facts have long been central to the case for Oxford’s authorship of the plays? So far, such fact-based, informed neutrality seems highly unlikely.

Analyzing the administrative exhibition documents and press associated with the 2016 First Folio tour reveals much about the Folger Library’s longstanding entrenched stance on the authorship question, and also gives insight into the library’s efforts to manage and control the messaging of the Folio tour. The tour guidelines show that the venues will be supplied with required display texts supporting the exhibit as well as educational materials, and that related programming is to follow certain prescribed themes.12 The required minimum of two “approved” scholarly speaker/contributors must have been screened in advance, as their credentials were to be included in the sites’ application packets. As one unorthodox scholar who prefers to remain anonymous put it, “the circumscribed qualifications required for speakers at the First Folio tour venues are a mirror of the fortified mentality of the Shakespearean status quo ante.”

Such precautions are not only unnecessary, but, as we will see, contradict the tour’s stated mission and contravene the founding free speech and inquiry missions of the institutions involved, particularly those of the ALA. In its publicity and programming for the tour, the Folger Library representatives seem poised, once again, to ignore if not suppress the plentiful research results that call the orthodox Shakespearean stasis into serious question, some discovered over the past century in documents from the Folger’s own prodigious collections. If that is their intention, the First Folio tour organizers will miss an opportunity to also engage a growing portion of their audiences who are either skeptical of the received view of authorship, or openly curious about the Oxfordian or other alternatives. They will miss the chance to promote the open and free inquiry that the national organizations involved, the ALA, the NEH, and the American Alliance of Museums (AAM) hopefully will insist upon.13

In preparing this report, the author has consulted numerous publicly available documents associated with the Folger tour. One primary text is the thorough Folger-ALA-CMC application guidelines14 that the local applicants followed in order to win the honor of hosting one of the First Folios. Also examined were numerous local newspaper items and press releases about the winning venues from spring 2015, and the mission and ethics statements of the Folger, ALA, and AAM. One pattern that emerges from this inquiry is the Folger’s consistently unimpressive track record of false neutrality in dealing with topics closely related to the authorship controversy. As much as Stratfordians need the folio to divert attention from the flawed nature of their biographical tradition, they are also—and not without good reason—afraid of it and somehow understand its destabilizing potential. This contradiction lies behind the library’s careful effort to closely control the exhibit’s messaging. The exhibit’s application guidelines detail the tour’s purpose, how venues were to apply to host the tour, the facility and program requirements, and the content or “themes” of the display panels that will accompany each Folio. The uniform press releases announcing the exhibition sites are formulaic, and show clear compliance with messaging management protocols of professional media hired to conduct a controversial campaign while minimizing real controversy and preventing unauthorized discussion. All the press releases, news items, and official announcements on the venue’s websites are more or less uniform in text, doing some or all of the following: announcing the venue, supplying quotations from Director Michael Witmore, describing the tour’s significance, offerings and content, quoting local project directors and their partners, adding praise and comments from local scholars – all following the same formula. The press clippings are too numerous to include or cite in this article, but Googling “First Folio” and any venue or host city name will turn up many press releases corresponding to this description.15

As of late fall 2015, only two of the fifty or more tour press releases had diverged from the prescribed or most likely “recommended” press release content. Staying “on topic” is, of course, usual and practical to keep an exhibit’s messages consistent. And in this case, compliance with specified messages seems a requirement of hosting the First Folio. However, because the authorship of the First Folio is controversial, and there is public awareness of the controversy, true neutrality is called for, especially by local hosts and the libraries and museums involved in the Tour. Invited speakers at an exhibit sponsored in part by the ALA, it really goes without saying, should be actively neutral, practicing an academic freedom that encourages broad inquiry and allows scholars to acknowledge doubts and diversity opinion in an atmosphere of civil discussion and debate. Under the circumstances, dissent should not just be tolerated, but encouraged; sponsoring organizations should lay active plans not just to allow, but to actively solicit multiple interpretations of the evidence contained in the first folio.

Unfortunately, better informing venue experts and moderators about the controversy to promote neutrality is inconsistent with the Folger’s traditional support, continued up until the present, for ignoring and/or ridiculing authorship questioning scholarship. In an April 7, 2015, Chicago Tribune web article announcing the Illinois venue for the Folio tour, Garland Scott, the Folger’s Director of External Relations, declares that, “The Folger believes that there’s nothing in [the] historical record that suggests anybody but a man named William Shakespeare from Stratford-on-Avon wrote these plays”16 (emphasis added). The journalist may not have been aware of the press release guidelines, but the topic in any case apparently came up. Granted, Scott is a spokesperson for the Folger, but is it proper to state that a library with a diverse staff of academicians and technicians “believes” such a specific, controversial claim? How far Scott’s uninformed and profoundly misleading claim jives with current Folger policy or intention for the tour remains to be seen, but it is consistent with the Library’s unfortunate history and, as we shall see, contemporary representations in other contexts.

Scott’s claim is problematic from several points of view. For one thing, according to the ALA, libraries are decidedly not supposed to take definitive positions of this sort on controversial scholarly matters. The authorship question has been rationally treated within recent memory in such publications as The New Yorker,17 The Atlantic,18 The University of Pennsylvania Law Review,19 The Tennessee Law Review,20 Harper’s,21 The Chronicle of Higher Education, and The New York Times,22 as well as being vigorously attacked on the internet on sites such as the Shakespeare Birthplace Trust (SBT). Of course, it was also considered at some length in a 2010 book by one of the Folger’s top consultants, James Shapiro, in his Contested Will. Were the distinguished publications misguided in thinking that there is more than one rational point of view about authorship, that there is in fact much in the “historical record” that contradicts the Folger’s party line? Another conspicuous flaw in Scott’s statement is her careful specification of only one kind of evidence—so-called “historical” evidence—to the exclusion of others. It is as if, ironically, the contents of the folios themselves do not constitute “evidence” or are unworthy of a forensic as well as literary and historical inquiry. In fact, abundant evidence of all kinds (including “historical”) contradicting Scott’s sweeping assertion is housed in the Folger’s own archives and even contained in the First Folio itself. Most disconcerting of all, such sound bites sweep under the rug several hundred years of revealing ambiguities, distortions and mysteries in the purportedly unquestionable case for William of Stratford-upon-Avon.

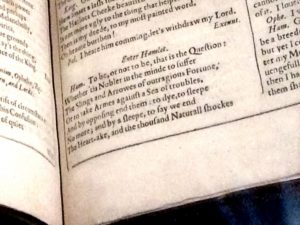

Considering this style of logic, in fact, it is ironic that the exhibition’s Folios will be displayed open to Hamlet’s “To be or not to be,” speech, with its heart-wrenching expression of identity crisis. To fit this situation, we might append the word “honest” or the “truly neutral” to the end of Hamlet’s question. The general public has perennially shown itself to be interested in the difficult question of Shakespearean authorial identity. A lot of people are aware that there is controversy over the current academic view of Shakespeare, and they prefer real answers. Unfortunately, early signs such as Scott’s fiat suggest that the Folger is preparing to quash public interest by banning the authorship question from the Folio tour. Yet the matter of authorship attribution of Shakespeare is not settled, and acting as if it is settled is not honest, neutral or fair.

As of this writing, only one exhibition director, from Oxford, Mississippi, has spoken outside the parameters of the standard Folger press release format, saying of the First Folio in his own words:

The historic significance is universal—an artifact from the early 1600s gets people thinking about how it was made, who made it, what was the culture like at that time and a variety of other perspectives that may or may not have anything to do with Shakespeare.23

These are examples of the honest questions about the circumstances of the Folio that many may wish to ask, expressed by someone who is either of an independent bent or who did not get the email. Despite what the Folger allegedly “believes,” Folio Tour participants have a right to consider various theories about “how it was made,” “who made it,” and what role it has played in the history of Shakespeare scholarship, whether they are interested in authorship or not. But are Folger tour spokespersons prepared to offer informed answers if the authorship question comes up? What if they get questions about the Folio itself that lead in unauthorized directions? We suggest they brief themselves with this special journal volume. The clichéd rejoinders may no longer work.

The exhibition itself, as indicated within the guidelines, is intended “to engage a large and diverse audience” and to “attract and engage constituencies that will sustain Folger presence and outreach in the area.”24 The bardolatry of Folger planners reveals itself in the exhibition’s statement of rhetorical purpose:

The First Folio itself is an iconic object, and one most people do not encounter in their lifetime. The goal of the exhibition is to bring this rich cultural artifact from a vault in the nation’s capital to communities across the country, and to bring communities to the Folio by providing context and programming designed to engage all audiences.25

The tour’s specific overall local objective is “to extend and deepen the impact of the connection to the First Folio for members of their community.”26 Insofar as they aim to share these splendid, rare, vaulted books with the general public, these goals are admirable ones. However, the guidelines also reveal that the provisioning of “context and programming” by local venues will be closely monitored by Folger/ ALA tour directors. The monitoring and data collection via required reports following the exhibit are required by the NEH grant, which asked the sites and the Folger tour supervisors to describe how they will document their grant participation in advance. Consistent with its mission, the guidelines state that the NEH wants to record “how fully the project met its stated learning goals and how audiences were more deeply engaged in thinking about humanities ideas and questions as a result of the project” (emphasis added). The Folger/ALA over-the-shoulder supervision and “message control” is clear from the application language; for example, under the heading of “Other General Requirements” for the sites, we find this:

[The h]ost must agree to work with the Folger and major sponsors to accommodate Folger and sponsor messaging, [my italics] activities, special events, or promotional activities that also meet host’s facility and promotional requirements. These activities will be paid for by sponsors and may involve data and promotional materials collection.27 (Emphases added)

Such prescriptions are troubling. Indeed, it is reasonable to wonder if an exhibition organized under such provisions of centralized control, especially when coupled with the Folger’s own selective and biased historical contextualization, can avoid contradicting the mandates of the sponsoring organizations to practice authentic neutrality. Whether the Folger’s tour programming inspires audiences to become “more deeply engaged in thinking about humanities ideas and questions” also remains to be seen. The NEH has, apparently, long been tolerant of the Folger’s dogmatism, having frequently sponsored past Folger events that have adhered to Stratfordian orthodoxy and actively excluded contrary views, the most recent being the Folger’s spring 2014 “Conference on the Problem of Biography.”28 But the American Library Association, with its admirable annual and ongoing freedom of speech campaigns, and the American Alliance of Museums, whose code of ethics specifies adherence to intellectual integrity and “respect [for] pluralistic values, traditions and concerns”29 also know better than to condone the suppression of alternative viewpoints in a topic under significant dispute.

The “hosting standards” within the exhibition guidelines outlined on the ALA site are clearly stated and many of the strictures are appropriate for travelling exhibitions, securing the revered documents as well as the safety of the public: “The objective of establishing these hosting standards and selection guidelines is to ensure that visitors of all ages in as many parts of the United States as possible get to experience a meaningful, safe, and memorable encounter with Shakespeare’s work.”30

Of course, the venues need to be secure and safe. However, how “meaningful” and “memorable” the exhibit itself will be for its diverse audiences depends to some extent, at least for a growing skeptical audience, upon how the Folger staff and its associated partners, as well as the local exhibitor spokespersons, choose to respond to challenges regarding the tour’s educational materials and message. Will they allow and respond positively to all inquiry including authorship questioning?

Descriptions of “required” educational and public programming followed by the phrases, “with materials provided by the Folger,” and “presented by qualified humanities scholars, on the humanities themes of the exhibition” should invite skeptical scrutiny by anyone interested in free inquiry. Of course, the people involved should be “qualified.” This would be all fine and good, if Folger officials stopped there. How has the Folger determined which humanities scholars are “qualified” and which are not? If past experience is any indication, anyone who might express a doubt about the Folger’s story of authorship is automatically disqualified. However, it is clear that the selection committee preferred to screen the scholars chosen by the venues to avoid controversy, as the applicants were required to

Provide the name and title of at least two scholars who will help you with local programming for the exhibition. Scholars should have specialties in literature, history, or the works of Shakespeare. Describe their experience with the topics of the exhibit and with programming for public audiences. Attach a vita or biography (up to two pages only) for each scholar in Section 6.A.

Then there is the specifying phrase, “on the themes emphasized in the exhibit.” Naturally, the rhetorical and spatial constraints for the physical exhibit’s panels require limitation to some topics. However, the description of the panels’ content in the application guidelines specifically outlines the exhibit’s “themes,” which unfortunately omit any actual cultural, political and historical context for what is termed a “rich cultural artifact.” Academic scholars who hold contrary views on authorship and who have “specialties in literature, history, or the works of Shakespeare” with expertise on the First Folio have not been consulted on the project.

The exhibit panels’ text and the accompanying programming content, as foreshadowed by the First Folio! The Book that Gave Us Shakespeare tour guidelines, will apparently deflect critical inquiry about the author and accept the most literal meaning of Ben Jonson’s lines that accompany the passing strange likeness of the author, “looke /Not on his Picture, but his Booke.” Shakespeare, the disembodied author, has, at least for the purposes of this tour, apparently morphed into an even greater non sequitur, “Shakespeare, the Book.” There remains much mystery surrounding the author, none of it solved by deflecting the controversy over the life onto the book, while simultaneously mystifying (mostly by complete erasure) the historical and cultural context of that book’s production. Ben Jonson, in the longer prefatory poem in the First Folio, defines Shakespeare as “not of an age,” for reasons that are not even universally agreed upon by orthodox Shakespearean-Jonsonian scholars, but which have been clarified by skeptical authorship scholarship.31

Some leading orthodox scholars are clearly aware that major problems with Shakespeare’s authorial biography cannot be solved within the current paradigm. This awareness-but-denial of the authorship problem became painfully obvious at the Folger Library’s own NEH-sponsored 2014 “Shakespeare and the Problem of Biography” Conference. The conference’s default solutions, when not taking the transparent fictional route, were to preselect presenters, deflect and ignore taboo questions about the author, while ridiculing32 those scholars (some present at the conference) whose work examines the biographical problem using evidence and logic. Instead, the conference orthodoxy employed creative rhetorical distractions such as the ad hominems that characterized the reactions of several conference speakers. One would think the best scholars of Shakespearean biography presenting in a publically funded, allegedly neutral library could construct more ethical rhetorical stratagems. Recently, another prestigious group, the Royal Shakespeare Company, was persuaded by the Shakespeare Authorship Coalition to remove from its website an ad hominem loaded blog entry by Stanley Wells that questioned the sanity of authorship doubters.33

The Folger and other institutional interests may wish to take note. Original or compelling arguments about authorship, which should be among many foci of unencumbered Shakespeare research, are belittled and ignored by Stratfordians at their own peril. It is not possible to engage in proper, evidence-based counter-scholarship without first assessing the arguments of an opposing side.

The 2016 First Folio exhibit materials as represented by the tour guidelines seem to avoid the topic of Shakespearean biography. Portraying the book as “an object with iconic cultural status,” a thrice-mentioned phrase of the ALA/Folger guidelines, is a central thematic emphasis of the First Folio exhibition. The themes, to summarize, include the First Folio’s:

- “Iconic universality”

- Cultural and educational appeal, value and popularity in America

- Textual variation, exemplified by surface details about the complex providence of Hamlet ‘s “To be or not to be” speech

- Status as a “landmark” document in the history of books.

Viewed from this perspective, and especially in light of the many highly relevant omissions in the tour’s advance publicity, the Folio tour seems more intended to deflect attention from the book’s disputed authorship than to educate tour attendees about the Folio as a cultural artifact. While these topics, minus the bardolatry,34 are reasonable and important aspects of Shakespeare studies, in the absence of more particular contextualization, the exhibition’s thematic emphases offer little opportunity for the kind of intellectual engagement that the folio tour purports to supply. Beyond the dubious biography-related claim that the First Folio preserves the controversial Droeshout engraving as “one of [the author’s] only authentic likenesses,” the program evades, rather than encounters, questions about authenticity and authorship, and even this claim of the posthumous Droeshout’s authenticity has never been proven and is still hotly disputed, even among traditionalists. 35 Claiming its legitimacy and unambiguous significance for fact, as the Folger does, is to ignore a long history of controversy that a publicly funded tour should embrace and invite. Instead we are treated to another version of the clichéd circular reasoning that “Shakespeare is Shakespeare,” a paper chase that fails to counter authorship questioning with evidence and arguably obscures the true historic meaning of document it purports to illuminate for the public. If the engraving is so “authentic,” why does editor Jonson tell us to look not on it, but on the book itself, to discover the author?

As we have noticed, another glaring omission from the Folger’s First Folio narrative concerns the earlier described roles of the Folio’s distinguished patrons and financiers, to whom the book conspicuously devotes two pages of introductory epistle, “THE MOST NOBLE AND INCOMPARABLE PAIR OF BRETHREN,” the earl of Montgomery, Susan de Vere’s husband, and his elder brother, the earl of Pembroke. Surely a museum-worthy display about an “iconic” literary artifact should consider the actual historical circumstances under which the book appeared in print, which prominently and undeniably include the patronage of the two brothers with such close ties to the de Vere family?

Nor do the Folger advance materials mention the striking political and cultural reality that the book was being published partly in response to a bitter three-year-long parliamentary controversy (1621-1624) over King James’s design to marry Prince Charles to a Catholic Spanish princess. The Folger also appears poised to sweep under the rug the long-standing scholarly dispute, dating back to the late 18th century, questioning the attribution of the Heminges and Condell prefaces, with many scholars suggesting that the real author of at least one of them was actually folio editor Jonson—a finding which, if true, automatically calls into question almost every other aspect of the folio’s genesis, design and intent.36 It is also ignoring contemporary scholarly inquiry into the striking and enormous ambiguities of Jonson’s prefatory contributions.37 Collectively these omissions confirm the impression already given in remarks such as Garland Scott’s that the Folger has no plan to explore any aspects of the Folio that don’t readily conform to its pre-established Stratfordian narrative.

What’s in a name anyway? Or, what’s in the name of a tour? The illogic of the First Folio! tour’s subtitle, The Book that Gave Us Shakespeare, which cleverly transfers authorial attribution to a physical object, parallels the doubtful logic of Scott’s attribution of uninformed personal belief to an institution of which she is an employee. This anonymous language removes not only the author from the discussion, but anyone with a contrary viewpoint. Such conspicuous gaps in logic suggest that some Folger librarians, as a symptom of their orthodoxy, are struggling with their own complex professional identity crises, especially if they paid any critical attention to the presentations and comments at the 2014 Folger Biography Conference. Despite the intentions of the Folger and its co-sponsors, the event afforded opportunity for some remarkable exchanges of ideas due to the presence of a number of informed Oxfordians.

Historically and legally, the authority behind the Folger rests with the Amherst College Trustees. They administer the Folger Library and have, as in the case of the Amherst Trustees’ Folger Committee Chair, Eustace Seligman, in the early 1960s, claimed neutrality vis-à-vis questioning authorial attribution: “The Trustees of the Folger Shakespeare Library have steadfastly refrained from in any way participating in the discussions as to the identity of the author of the plays credited to William Shakespeare.”38 Seligman’s “steadfastly” seems to indicate a mandate. It would seem that the Folger’s mission prescribes neutrality. Unfortunately, as any review of the evidence indicates, and continuing to the present as manifest in Scott’s statement and in the abridged character of the Folio Tour materials, the Folger’s neutrality has never been authentic. Amherst Trustees have for decades winked at the partisan behavior of both directors and staff avowing “neutrality.” As former Folger Educational Programs director Richmond Crinkley (1969-1973), described the situation in 1985: “As one who found himself a contented agnostic Stratfordian at the Folger, I was enormously surprised at what can only be described as the viciousness toward anti-Stratfordian sentiments expressed by so many otherwise rational and courteous scholars. In its extreme forms the hatred of unorthodoxy was like some bizarre mutant racism.”39 All too frequently, flimsy claims of impartiality have served to mask the Folger’s public authorship stance by excluding questions and answers that do not fit the Stratford narrative.

The fusion of individual psychology with scholarly inquiry may be nowhere more apparent than in the recent Folger leadership’s public dealings with the authorship question as evidenced by mentions on the library’s official website. Examining the Folger current and archived website materials on authorship question is revealing. On an archived version of their website (old.folger.edu), the current Folger Library Director, Dr. Michael Witmore, was directly quoted stating a qualified openness to future scholarly inquiry about authorship. The same statement (included below) resides, now sans attribution to Witmore, in the educational portion of the Library’s recently updated website, titled “Questioning Shakespeare’s Authorship.” The current website’s now seemingly generic Folger-authored FAQ paragraph, no longer assigned Witmore’s name but otherwise unaltered, also states blatantly— between dashes—that “no decisive evidence has been unearthed thus far”:

The Folger Shakespeare Library has been a major location for research into the authorship question, and welcomes scholars looking for new evidence that sheds light on the plays’ origins. If the current consensus on the authorship of the plays and poems is ever overturned—no decisive evidence has been unearthed thus far proving that the plays were produced by anyone but the man from Stratford-upon-Avon—it will be because new and extraordinary evidence is discovered. The Folger is the most likely place for such an unlikely discovery.40

Playing the disingenuous “no-evidence” card is decidedly not neutral of Witmore (whether he takes credit for the paragraph or not), nor of the Folger Library, and seems quite stale after decades of repetition. This reductive claim rings especially hollow after decades of repetition, especially to those Oxfordians whose scholarly work (some of it done at the Folger) has repeatedly discovered, carefully analyzed, and shed “decisive, new and extraordinary” light on the genesis of the plays, sometimes via peer-reviewed mainstream journals, or in leading intellectual venues like Harper’s, The Atlantic, or The New Yorker, or books with academic publishers. Witmore’s carefully-shaded claim on the archived Folger authorship page was unfortunate enough, but now the attributed version has been relegated to the archives, and the library repeats Witmore’s words in an anonymous section of educational material, as a disembodied an unattributable claim of fact bearing the Folger’s general seal of approval.41 Instead of being the opinion of a moral agent, it is now presented as the unanimous opinion of an anonymous institution. Under “Shakespeare Frequently Asked Questions” the Folger asks, “Did Shakespeare write the plays and poems attributed to him?” Here Witmore’s “no evidence” claim is repeated in the remarkably inaccurate summary: “In the century [sic] since these claims were first advanced, no decisive evidence [sic] has been unearthed proving that the plays were produced by anyone but the man from Stratford-upon-Avon.”42

Consider the contradiction: the Folger website now represents an opinion about the authorship question among those frequently asked, but fails to indicate that this is a controversial, disputed claim or to point the reader to any of the many online resources that might provide an alternative perspective. This perilous territory is negotiated by the precise, premeditated placement of the weasel word, “decisive.” Elevated to the library’s own belief, the statement exemplifies the Folger’s unofficial tradition, since the 1980s, of allowing research privileges to nonconformists, while actively suppressing the results of their research because it does not meet some unexamined standard of “decisive” proof—as if anything approaching “decisive proof ” existed on the orthodox side! The entirely oxymoronic implication is that the standard for academic inference is that one side in a debate should possess “decisive proof ” before evidence on either side can be considered or debated. It does not take an advanced degree in Shakespeare studies to recognize that this is not neutrality. It is also not progress.

The Folger’s history of faulty neutrality may be placed in its correct historical and cultural context when we consider Director Witmore’s most recent public comments on authorship. In a November 27, 2014, interview, Folger biographer Stephen Grant quotes Witmore as believing that “the Folger does not have opinions. It has collections.”43 One wonders how Witmore can reconcile this statement with the undisputed fact that the organization’s website claim, originally quoted as the Director’s own opinion, that “no evidence” contradicts belief in the orthodox story. This is, surely, expressing an opinion, and a poorly informed one at that. Stating that no evidence exists when thousands of people know that it does is not neutrality.

An April 29, 2015, C-SPAN interview about the Folger’s role in the nation’s political and cultural life further underscores the intrinsically contradictory rhetoric on which the Folger’s current position depends. In the interview, Witmore recounts the Folger visit of several Supreme Court justices (exact number unknown, according to Folger sources). Debating the authorship question among themselves, the Justices popped over to the library to view a specific Folger treasure, Edward de Vere, the 17th Earl of Oxford’s Geneva Bible.44 Assuring his audience of the library’s readiness to accommodate authorship scholars such as Supreme Court Justices, Witmore did not bother to detail the reason for the interest in the de Vere Bible: twentieth century American Oxfordian research links de Vere’s handwritten annotations thematically to the plays.45 The interview hung in the rarefied air of SCOTUS prestige and went onto the next topic.

Witmore, of course, clearly suspects or knows what the Supremes knew— namely that there is probative, if not entirely persuasive to everyone, clear and unequivocal evidence of alternate authorship in the Folger’s very own vaunted book vaults. Why, then, is he acting as if this evidence still doesn’t exist? In addition to Roger Stritmatter’s dissertation connecting that Bible in tangible, material ways, to the plays, other Oxfordians have made discoveries at the Folger—two generations of Ogburns, Charlton and his parents, and Georgetown University’s Richard Waugaman, among others, have extensively utilized the Library’s holdings and made original discoveries that merit the Library’s attention. As a Folger reader, Charles Wisner Barrell discovered that the Folger-held Cornwallis-Lysons manuscript represents a direct link between Oxford and Shakespeare via the Bohemian London townhouse known as Fisher’s Folly.46 Others have questioned the Folger’s position on the Ashbourne portrait, for which it now claims a dubious identification without having seriously analyzed its provenance or judiciously considered other existing evidence that it is actually the lost Cornelius Ketel portrait of Oxford (see note 37).

It should not surprise Witmore that the Supreme Court justices are interested in the evidence for the authorship question. It is no secret at all that at least five former Justices—Blackmun, Powell, O’Connor, Stevens and Scalia—have been sympathetic to the Oxfordian case (others, currently on the bench, are said to be authorship doubters)47 and are openly interested in research done at the Folger including but not limited to Stritmatter’s. Research supporting the Oxfordian theory of authorship that has been done at the Folger is only unknown to those librarians and scholars who ignore the publications documenting it.

There are several clear indications that Henry Clay Folger, in his original curatorship and stewardship, wanted the archive not only to allow, but to actively encourage, free inquiry into every aspect of Shakespeare, including authorship. If so, this conviction has been obscured, sometimes by intent, in the decades since Folger’s death. Biographer Grant, for one, insists that

The Folgers believed profoundly that Shakespeare wrote Shakespeare. Secondly, despite that belief they acquired all the books and articles they could about the authorship controversy. Their goal was to assemble as complete a Shakespeare collection as possible, to be of increased usefulness to the researchers, scholars and professors.48

And yet Grant, in his biography, cites no source for his sweeping knowledge of the Folgers’ convictions. Gail Kern Paster, a former director (2002-2011), also claims no knowledge of the founders’ intentions. A 2007 Amherst Magazine interview records Paster’s belief that

Folger’s exact motives in acquiring the collection, and in creating the library, remain elusive: “It’s really hard to get a sense of his own inner conversation,” says Paster, [then] the library’s current director. “He’s like Hamlet: There’s a mystery in there that we really can’t pluck the heart out of.49

It may be difficult to accurately understand Henry Folger’s mind on authorship, but it is obvious that comments like Paster’s do more to conceal the complex truth of his views than to make them manifest; the solution to this mystery may come instead from the prodigious neutrality and inclusiveness of the original collection itself. Although the image and legacy of this very private and secretive man, especially on any topic related to authorship, have been so carefully managed by predominantly Stratfordian-predisposed Folger administrations over many decades that it is difficult to feel certain how he felt, the evidence does not support the claim that Folger devoutly followed the Stratfordian belief. The Folger archives contain many valuable materials collected by the Folgers themselves that contribute to the alternative cases for authorship, including the aforementioned de Vere Geneva Bible, an Oxfordian novel by a major American writer and its manuscript,50 an altered portrait that is probably that of the seventeenth earl of Oxford,51 and extensive Baconian, Oxfordian, and Marlovian holdings, as well as documents related to other candidates. Grant later claims that “Emily and Henry…harbored no doubts”52 about the authorship question. He justifies this inference through a single quotation, in which Folger, late in his life, allegedly told a book dealer that his interest in Bacon was ended.

This would have been just about the time Folger was corresponding with Oxfordian novelist Esther Singleton, whom he’d known since at least 1922,53 and intending to acquire the manuscript, today still in the Library’s possession, of her whimsical Oxfordian novel, Shakespearian Fantasias: Adventures in the Fourth Dimension. This exchange was almost ten years after the 1920 publication of J. Thomas Looney’s “Shakespeare” Identified in Edward de Vere, 17th Earl of Oxford, which was instrumental in converting Singleton, Freud, and others to the Oxfordian case. Needless to say, the quotation does not justify the biographer’s claim, but only confirms, as other evidence suggests, that by the late 1920s Folger was no longer interested in Bacon because he may have realized that a more compelling alternative to the orthodox account was Oxford, which incidentally would explain his interest as well in the de Vere Geneva Bible, which he purchased in 1925. His last will and testament stipulates no particular candidate, only that his library be available for the study of “Shakespeare.”

Several Oxfordian discoveries owe much to the Folger Library’s broad holdings, amassed by Folger himself. For this reason, and because of the noncommittal bequest in Folger’s will, the neutrality claimed by the Amherst Trustees as well as past and present Folger Directors would be an appropriate stance, were it genuinely adhered to. So far as allowing researchers to frequent the reading room, neutral access is allowed and the reading room librarians, at least since the early 1990s, have been courteous and professional in all their dealings with authorship skeptics. However, Folger administrative practice and public statement with regard to the discoveries themselves has all too often contradicted the library’s own neutrality claims.

This neglect of a deeper and more authentic neutrality, all too conspicuous in the press coverage leading up to the tour, has in the past interfered with the Library’s fiduciary responsibility as an institution receiving federal funding, not to mention furthering the mission of its visionary founders, who acquired such rich resources for authorship studies. Sadly, the evidence discovered by authorship researchers since the 1920 publication of “Shakespeare” Identified, some through the Library’s above-mentioned documents, has long been ignored or misrepresented by Folger administrators among other organs of the Shakespeare establishment. Charlton Ogburn, Jr. (1911-1998), a leading second-generation Oxfordian scholar, who did much of his research at the Folger in the last century, documents the fact that his extensive work was not received with reasonable consideration, but countered with contemptuous ad hominems by then Folger director (1948-1968) Louis B. Wright.54 In his 1968 book, The Folger Library: Two Decades of Growth: An Informal Account, Wright exemplifies the contra-indicated neutrality that seems to have been endemic at the library as early as the reign of Giles Dawson:

No one has disproved a mite of the evidence that Shakespeare of Stratford is the author of the plays that bear his name, or that anyone else wrote them. The Folger Library has no partisan concern to maintain the authorship of anyone. We simply do not have the time and patience to waste in arid sophistries and futile hypotheses. If anyone ever produced a single bit of genuine evidence to disprove Shakespeare’s authorship or to establish another, every Elizabethan scholar in the land would assist in testing the evidence.55

Here Wright was being mild, compared to his attacks on Ogburn, but what he was willing to say here in scholarly print belies the neutrality supposedly mandated by the Amherst Trustees. Such disdain is far from neutrality. Wright’s last statement that scholars would come running to help could not be more dishonest—in reality, the Folger directors have mostly ignored and refused to (openly) talk, read or hear about, let alone help test, Oxfordian findings.

Fortunately, the Folger does have some history in a more tolerant mode. O. B. Hardison, Director from 1969 to 1983, made an effort to create a more collegial atmosphere and promote the value of conflicting viewpoints. Under Hardison, Richmond Crinkley even favorably reviewed Ogburn’s book56 in the library’s Shakespeare Quarterly. Crinkley fairly summarized both Ogburn’s position and his character: “Among the most congenial of men, Ogburn felt, rightly in my opinion, that such treatment violated the benign neutrality with which libraries should properly regard intellectual controversy. It was hard to dispute Ogburn.”57 Crinkley was a Folger administrator of rare knowledge and leadership, who saw the value of acknowledging varied perspectives on authorship and freely admitted that the orthodox view suffered from dramatic points of implausibility. Crinkley had recommended that the Folger change its tune. His review essay on Ogburn’s findings represents a rare attempt by a leading Stratfordian to analyze authorship arguments as part of a fact-based inquiry. Relations between the Folger and leading skeptical scholars did temporarily improve, but by the next regime regressed back to the false neutrality that continues today.

The newest anniversary-celebrant Folger traveling exhibition, the Folio Tour, represents a new opportunity for the renowned Shakespeare library to break new ground by achieving some objectivity by subjecting its own assumptions to rigorous review and considering formerly prohibited perspectives. It will be an even more wondrous success if the message that accompanies the books around the country can be inclusive and exploratory rather than dogmatic and insular. Authorship scholars and the skeptical curious can and do pursue truths in Shakespeare just as keenly as professional, tenured academics; censoring the findings they have brought to light, sometimes from the Folger’s own collection, is not the scholarship that either the Folger or the ALA is supposed to foster. Ben Jonson’s biographer, Ian Donaldson, unlike some early modern scholars, has recognized the value of such dissent about the “facts”: “Counterfactual history, when openly practiced, has the power to stretch and stimulate the mind.”58 One-sided inquiry that proclaims neutrality while ignoring mountains of credible and persuasive evidence on the other side is neither true scholarship nor free speech. Loyalty to one point of view for tradition’s sake is far from neutrality. So it is with Macbeth’s tragic fault, as he attempts to be both “loyal and neutral, in a moment.”59

The Folger hopes to take its mission national once again with this tour, and one can hope it is done with an accountability appropriate to the complex questions raised by the folio’s existence and historical contexts. A major administrative collaborator with the Folger on the Folio Tour is the American Library Association’s Public Programs Office. Most of the libraries hosting or assisting with the exhibition also belong to the ALA. While all participants clearly have the right to their own opinions on the matter, should any Folger administrators or librarians, obedient tour exhibitors, local theater or scholarly experts supporting the tour publicly refuse to allow or denigrate any discussion of the authorship question, those responsible will have likely forsaken their organizational missions, especially as librarians. They should remind themselves and their venues of the importance of genuine neutrality. The ALA Bill of Rights state that basic ALA and library policies should insure that

Materials should not be excluded because of the origin, background, or views of those contributing to their creation (I) Libraries should provide materials and information presenting all points of view on current and historical issues. Materials should not be proscribed or removed because of partisan or doctrinal disapproval (II). Libraries should challenge censorship in the fulfillment of their responsibility to provide information and enlightenment (III). Libraries should cooperate with all persons and groups concerned with resisting abridgment of free expression and free access to ideas (IV).60

According to these principles, any public libraries or museums hosting the Folio should have complete freedom to offer their own programming and to invite appropriate speakers as they see fit. Members of the public should be allowed to ask questions about the authorship of the iconic text and should be able to expect reasonable, evidence-based answers or neutral responses.

The “Interpretations of the Library of Bill of Rights” page on the ALA site is even more explicit about these speech and academic freedoms, applying them to content and information access.61 Thus, if the messaging and programming for First Folio! The Book that Gave Us Shakespeare, does not shift to genuinely neutral ground, the tour’s policies and practices will be clearly inconsistent with the collaborating public institutions’ and their professional associations’ ethical statements. If the Folger Shakespeare Library’s goals include expanding the its own relevance to a broader audience by encouraging the appreciation and study of Shakespeare and promoting critical thinking about humanities and culture, Folger administrators really need to step up. It is time to cultivate true neutrality and recognize the scholarly fruits of free inquiry. The 2016 exhibition will have the travelling First Folios open for the public to see. Figuratively, the book should also be open to all questions that Shakespeare’s powerful works inspire. Answers to questions not within the moderator or speaker’s expertise can be met with referrals for further inquiry.

Unfortunately, nothing in the Folger’s advance publicity or historic track record suggests that this is what the Library has in mind for the 2016 Folio tour.

In other words, Oxfordians believe that Shakespeare, the mysterious author, would be even more compelling and relevant to future generations if he and his book were not treated as branded icons for uncritical adoration, but as the work of a gifted but real human being who strove to illuminate the human condition in his drama. Rather than suppressing the controversial enigmas of the Stratfordian paradigm, the Folger and the First Folio exhibitors should allow the public to ask all potential questions about Shakespeare and his plays and poems, and when they can, give balanced, unbiased answers or refer to accessible, diverse sources, including those that express contrary opinions. They should admit that some questions have not yet been answered. As stewards of the Shakespeare and Folger legacies, as representatives of a powerful academic institution accepting public funding, Folger librarians and publicists should perform this service with courageous conscience, avoiding both the errors of censorship and the legacy of misinformation that have for so long plagued traditional Shakespeare scholarship and created so much basis for legitimate doubt.

Shelly Maycock has taught Composition and Professional Writing as an Instructor at Virginia Tech since 2007. She has two MAs in English literature and creative writing from Virginia Tech and Hollins University. In the interim, she enjoyed a first career in bookselling and travelled widely as an independent trade publishers’ sales rep. She developed authorship skepticism as an English major and grad student fascinated with Elizabethans but became disenchanted with the traditional view of Shakespeare, and developed a strong interest in the Oxfordian position after studying and later teaching Hamlet, taking up early modern research and encountering Anderson’s Shakespeare by Another Name.

Endnotes

- Sonnet 111.5.

- A Midsummer Night’s Dream, 5.1.

- “Programming: ‘First Folio! The Book that Gave Us Shakespeare,” American Library Association Public Programs Office, accessed June 20, 2015.

- The full foundation name is the Google Inc. Charitable Giving Fund of Tides Foundation.

- Ogburn, Charlton, Jr. The Mysterious William Shakespeare: The Myth & the Reality. (McLean, VA: EPM, 1992), 69.

- Marx, Bill. “Fuse Commentary: Not Just Shakespeare—‘Anonymous’ Wrongs Ben Jonson As Well.” Artsfuse. Nov. 8, 2011. Accessed July 5, 2015.

- Rendall, Gerald H. Ben Jonson and the First Folio Edition of Shakespeare’s Plays. (Colchester: Benham & Co 1939), 7.

- For further information, many of these publications on the various arguments are available by searching scholarly databases and discovery engines with the key words, “Shakespeare authorship” and “Oxfordian.” For the American organizations representing alternative points of view, see doubtaboutwill.org and shakespeareoxfordfellowship.org. Also see the New England Shakespeare Oxford Library site: shakespeareoxfordlibrary.org/. The third (2015) edition of James Warren’s An Index to Oxfordian Publications: Including Oxfordian Books And Selected Articles From Non-Oxfordian Publications (Somerville, MA: Forever Press, 2015) now lists more than 6,500 entries on the Oxfordian theory of authorship. The index is available from Amazon.com.

- On the history of the authorship question, see esp. Warren Hope and Kim Holston, The Shakespeare Controversy: An Analysis of the Claimants to Authorship, and Their Champions and Detractors (Jefferson, N.C.: McFarland & Co, 1992), or the updated 2nd edition (2009).

- “Guidelines: Shakespeare and His First Folio: A Traveling Exhibition.” American Library Association Public Programs Office, last updated 6 June 2014, accessed June 20, 2015.

- Another of Oxford’s daughters, Elizabeth (1575-1627) was married to William Stanley (1561-1642), the literary 6th Earl Derby, who is reported by the Jesuit spy George Fenner circa 1599 to be “busy penning plays for the common players.” As Peter Dickson has noted, Thomas Walkley, the publisher of the 1622 renegade quarto of Othello, was a house printer to the Earls of Derby and used a Derby heraldic device – the eagle and child – on the issue of the Shakespearean play [Bardgate: Shake-speare and the Royalists Who Stole the Bard (Mt. Vernon, OH: Printing Arts Press, 2011): 151-156].

- “Guidelines.”

- “Code of Ethics for Museums,” American Alliance of Museums, accessed June 20, 2015.

- “Guidelines.”

- For a list of host cities and venues, in chronological order, see the Folger’s online pdf, “First Folio! The Book that Gave Us Shakespeare: 2016 National Tour” Accessed Nov. 18, 2015.

- DeVore, Sheryl. “Discovery Museum to Celebrate Shakespeare’s 400th Death Anniversary.” The Lake County Sun-News (Illinois). April 7, 2015.

- Lardner, James. “The Authorship Question.” The New Yorker. April 11, 1988, 87.

- Bethell, Tom. “The Case for Oxford.” The Atlantic Monthly. 268, no. 4 (October 1991): 45-61.

- Stevens, John Paul. “The Shakespeare Canon of Statutory Construction.” The University of Pennsylvania Law Review. 140 (1992): 1373-87.

- The Tennessee Law Review. Entire Fall 2004 issue.

- Bethell, Tom, et al. “The Ghost Of Shakespeare.” Harper’s, April 1999 (298: 1787), 35-62, which contains debate texts by Tom Bethell, Daniel Wright, Mark K. Anderson, Joseph Sobran, Richard F. Whalen, Gail Kern Paster, Marjorie Garber, Irvin Matus, Harold Bloom, and Jonathan Bate.

- Niederkorn, William S. “A Historic Whodunit: If Shakespeare Didn’t, Who Did?” The New York Times, February 10, 2002.

- Norm Easterbrook, “UM to host first folio exhibit.” Oxford Eagle Online (Oxford MS), Feb. 26, 2015, accessed June 18, 2015.

- “Guidelines.”

- “Guidelines.”

- “Guidelines.”

- “Guidelines.”

- For one leading Oxfordian’s provocative observations on this conference, see Roger Stritmatter, “Aloha Vere: Folger Library Confronts ‘Problems’ of Shakespearean Biography.” Shake-Speare’s Bible. April 7, 2014. Accessed August 1, 2015. The author also attended this conference.

- “Code of Ethics for Museums,” American Alliance of Museums.

- “Guidelines.”

- This special 2016 volume of Brief Chronicles surveys some of the outstanding post-Stratfordian scholarship on the Folio.

- The conference was not a conventional or typically accountable academic conference, as presenters were preselected without an impartial, open call for papers. While there were veteran, well-published academic authorship scholars present, the best that the preselected conferees at the 2014 Folger’s Conference on the Problem of Biography could do was to sponsor a leading orthodox scholar’s presentation on one Baconian’s authorship cipher obsession, while repeatedly dropping the name of Delia Bacon, a 19th century authorship scholar who had a mental breakdown. In all fairness, some conferees engaged authorship scholars in collegial, if guarded, discussions about particulars of actual research, at lunch and between sessions. However, it seemed very clear that the presenters were told or had agreed in advance to avoid topics relating to alternate author theories. Graham Holderness was the lone scholar to break the conference taboo in order to hold up the example of the fictional movie Anonymous as an exhibit to somehow refute Oxfordian scholarship. He did not seem aware that Oxfordians recognize the fictional nature of the film and its inconsistencies.

Holderness misrepresented the film as depicting “an author disconnected from the theater,” which ignores the film’s depiction of young de Vere producing a play for the queen and later attending the public theaters. Further, via letter to Richard Waugaman of Georgetown University, conference participant Stephen Greenblatt retracted an offensive remark made that week to the Washington Post about the conference, comparing authorship-questioning scholars to Holocaust deniers, though he continued to endorse and employ other, less-fraught but still insulting, similes. Recently, the Royal Shakespeare Company has been compelled by the Shakespeare Authorship Coalition to remove an article that made false claims about the psychology of authorship doubters from its website. See note 33. Arguing authorship, which should be one focus of unencumbered Shakespeare research, is constantly made fun of but rarely the topic of informed opinion or honest counterarguments. These are just a few recent examples that compound of a long history of insults. - “Royal Shakespeare Company Website Retracts False Claims about Authorship Doubters,” The Shakespeare Oxford Fellowship website, accessed June 20, 2015.

- Commonly defined as “the worship, particularly when considered excessive, of William Shakespeare,” bardolatry goes hand in hand with the Stratfordian position because it makes the author a mythical figure rather than a genuine human being, which helps smooth over the problems with Shakespearean biography.

- The authenticity of the Droeshout engraving has long been a vexed question. Stanley Wells of the Shakespeare Birthplace Trust, in a counterpoint captured on the Folger’s Shakespeare Quarterly Forum blog, pointed out the Droeshout’s dubious status in the following remark concerning the Cobbe portrait: “The greatest weakness in Dr. Bearman’s arguments is that he assumes as a given that the Droeshout engraving and the bust in Holy Trinity Church, Stratford, are ‘the two authentic images’ of Shakespeare, yet both are posthumous. I know of no other cases save, perhaps, those of Christ and of Antinous when a posthumous portrait is regarded as reliable evidence for a likeness, however much contemporaries, with the subject no longer there to act as a touchstone, may have averred that it was.” Stanley Wells, “Response” to Robert Bearman, “The ‘Cobbe’ Portrait of William Shakespeare.” “Shakespeare Portraits and Controversies,” Shakespeare Quarterly Forum. 6 May 2011. Accessed November 12, 2015. Wells is also referring to Robert Bearman’s review of the revised edition of Shakespeare Found! A Life Portrait at Last, edited by Stanley Wells in Shakespeare Quarterly. 62:2 (Summer 2011), 281-284.

- The idea that Jonson at least wrote the Heminges and Condell preface “To the Great Variety of Readers” (A3) goes back a long way and continues to the present; Steevens first thought of it in 1770 and Malone included it and seconded it in his edition (Malone, Edmund. The Plays and Poems of William Shakespeare. Vol. II. [1821], 663). W. G. Clark and T. Glover’s Preface to the Cambridge Shakespeare (1863) suggests that the prefaces were “written by some literary man” (270 n. 1). W. W. Greg (The Shakespeare First Folio, Its Bibliographical And Textual History. Oxford: Clarendon Press, 1955) discusses the case for Jonson’s authorship of the poem, including George Greenwood’s critique, and seems convinced (17-26), which argument is cited by Leah Marcus as support for her assertions about the ambiguity of the prefatory poems (see note 23). More recently, Ian Donaldson agrees that Jonson wrote much of the epistle to the readers in general in his Ben Jonson: A Life (Oxford: OUP, 2011): 370-374.

- That Jonson cannot be read only literally is a consistent theme from early in Shakespeare-Jonson scholarship up to the present. Jonson’s ambiguities are a constant in scholarship past and present. See Whalen, Richard, F. Chapter 11: “The Ambiguous Ben Jonson: Implications for Assessing the Validity of the First Folio Testimony” in Shahan, John M., and Alexander Waugh. Shakespeare Beyond Doubt?: Exposing An Industry In Denial. (Plantation, FL: Lumina, 2013), 126-135.

As William Slights, in 1994, expressed this doubt, “I have become convinced that the driving social force, distinctive dramatic techniques, and persistent interpretive puzzles in [Jonson’s plays] are related in one way or another to the topic of secrecy.” Slights, William W. E., Ben Jonson and the Art of Secrecy (Buffalo, NY: U of Toronto Press, 1994), 14.

Vanderbilt’s Leah Marcus in her Puzzling Shakespeare (Oakland: U Cal P, 1988) argues that the reader is disoriented by the juxtaposition of the Droeshout portrait and the Jonson poem, which confounds the very perceptions it invokes. “[The folio] makes high claims for ‘The Author’ while simultaneously dispersing authorial identity; so that ‘Mr. William Shakespeare’ becomes almost an abstraction, a generic category, while remaining an unstable composite. Given the rhetorical turbulence of the volume’s introductory materials, constructing Shakespeare requires almost a leap of faith, like Jonson’s, and depends upon the suppression of a host of particulars that recede into indeterminacy when an attempt is made to pin them down (24-25). See Stritmater review, pp. 103-109 this volume.

On the general ambiguity of early modern prefatory poems, Cannan’s analysis of Jonson and his prefaces in their literary context [Cannan, Paul D. “Ben Jonson, Authorship, and the Rhetoric of English Dramatic Prefatory Criticism.” Studies in Philology 99:2 (Spring 2002): 178-201], suggests that “discerning Jonson’s – or any playwright’s –place in the history of authorship requires an understanding of contemporary attitudes toward the theater, dramatists, and play publication. Unfortunately, the information we have regarding these topics is scrappy at best, and especially when appearing in prefatory matter, is frequently packaged in elusive rhetoric” (my emphasis, 180). Cannan later explains after many examples of prefatory writing in Jonson and others that early modern authors were working in a medium of “mixed messages on dedicating plays,” and declares “the single most common feature of prefatory matter during this period” was “its contradictory nature” (186). Orthodox literary analysis has ignored these aspects along with the censorship and political realities that shaped such messages, a process carefully delineated in Annabel Patterson’s ground-breaking work, mainly about Jonson, Censorship and interpretation: The Conditions Of Writing and Reading in Early Modern England (Madison: University of Wisconsin Press, 1984). - Ogburn, 792.

- Richmond Crinkley, “Perspectives on the Authorship Question,” Shakespeare Quarterly 36:4 (Winter 1985): 515-522.

- “Questioning Shakespeare’s Authorship.” Folger Shakespeare Library Online Archive, accessed June 2, 2015.

- “Questioning Shakespeare’s Authorship.” accessed June 2, 2015.

- 42. “Shakespeare FAQ: Shakespeare’s works: Did Shakespeare write the plays and poems attributed to him?” Folger Shakespeare Library, accessed June 28, 2015.

- 43. “Local Author Zeroes in on Folgers, Shakespeare” Interview. Steven Grant. Arlington Sun Gazette. (Arlington, VA) November 27, 2014, accessed June 16, 2015.

- “Q&A with Michael Witmore.” C-SPAN. Web interview, April 29, 2015. (00:57:55). Accessed June 18, 2015.

- Stritmatter, Roger A. 2001. The Marginalia of Edward De Vere’s Geneva Bible: Providential Discovery, Literary Reasoning, and Historical Consequence. Ph.D. diss., (U Mass-Amherst. Department of Comparative Literature) ProQuest, UMI Dissertations Publishing.

- The Cornwallis-Lysons manuscript at Folger Shakespeare Library, circa 1585-90, contains the earliest known copy of any portion of “Shakespeare’s” works, predating Venus and Adonis by several years, a poem later appearing in The Passionate Pilgrim in 1599 (as poem XIX) as attributed to “Shakespeare,” as well as several poems attributed to de Vere. The (probably 18th c.) spine reads “MSS POEMS BY VERE EARL OF OXFORD &C,” Charles Wisner Barrell, “Earliest Authenticated “Shakespeare” Transcript Found With Oxford’s Personal Poems: A Solution of the Significant Proximity of Certain Verses in a Unique Elizabethan Manuscript Anthology,” The Shakespeare Fellowship Quarterly, April 1945. Also see Miller, Ruth Loyd in an article originally published as: Chapter XVIII (369-394) in Oxfordian Vistas (Vol. 2 of Shakespeare Identified. Kennikat Press, 1975. Ed. by Ruth Loyd Miller). Orthodox commentary on the manuscript appears in William H. Bond, “The Cornwallis-Lysons Manuscript and the Poems of John Bentley,” Joseph Quincy Adams Memorial Studies, ed. James G. McManaway, Giles E. Dawson, and Edwin E. Willoughby (Washington, DC, 1948), 683-693, and in Arthur F. Marotti, “Folger MSS V.a.89 and V.a.345: Reading Lyric Poetry in Manuscript,” in The Reader Revealed, ed. Sabrina Alcorn Baron, et al. (Folger Shakespeare Library, Washington, DC, 2001), 44-57.

- Bravin, Jess, “Justice Stevens Renders an Opinion on Who Wrote Shakespeare’s Plays” Wall Street Journal, April 18, 2009, accessed October 10, 2015. Bravin says, “Justice Stevens can indulge his love of the Bard at the Folger Shakespeare Library, a block from the Supreme Court. He says he had a particular brainstorm after learning the library held a Bible that once belonged to de Vere.”

- 48. “Local Author Zeroes in on Folgers, Shakespeare.” Steven Grant. Arlington Sun Gazette. (Arlington, VA) November 27, 2014, accessed June 16, 2015.

- Goldscheider, Eric, “An Unlikely Love Affair” Amherst Magazine Fall 2007, accessed June 23, 2015.

- Esther Singleton’s Shakespearian Fantasias, a 1929 Oxfordian novel that the Folger owns in manuscript form. According to the editors of the Shakespeare-Oxford Society, American branch newsletter 1940, Henry Clay Folger was arranging to buy the manuscript just before his death, but it was later donated to fulfill his wishes posthumously after Singleton also died (“Editor’s Note.” at end of Singleton’s “Was Edward de Vere Shakespeare?” report in Shakespeare Oxford Newsletter, Autumn 1973, 15. ShakespeareOxfordFellowship.org “Publications”). The Folger’s copy of Singleton’s published novel is inscribed by its author to Henry Clay Folger. The Folger’s copy of one of her previous books, The Shakespeare Garden (1922) is also inscribed to him in the year of publication, confirming an association between Folger and Singleton of at least eight years duration.

- The Ashborne Portrait. There are several articles that contradict the Folger’s evidence-thin authority on this, William L. Pressley, and the version of the Portrait’s story on the Folger website. Pressley’s account is given in the rather aptly titled, “The Ashbourne Portrait of Shakespeare: Through the Looking Glass” Shakespeare Quarterly, 44, no. 1: 54-72. For a superb overview of the Oxfordian evidence, with references to all the “state of the art” prior literature, see Jeremy Crick and Dorna Bewley, “The ‘Ashbourne’ Portrait: New Research,” De Vere Society Newsletter, Summer 2007, 24-35.

- Grant, Stephen Collecting Shakespeare (Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press. Kindle Edition. 2014), 78.

- Singleton’s The Shakespeare Garden, held by the Folger Library, is inscribed in 1922 to Henry Clay Folger.

- See the chronicle of many assaults on Ogburn’s work by following the references to “Folger Shakespeare Library” from his The Mysterious William Shakespeare’s index and more particular, the references to Wright’s own language. Granted, intolerance is not exclusive to Stratfordians [see Warren Hope and Kim Holston, The Shakespeare Controversy: An Analysis of the Authorship Theories, Second Edition (Jefferson NC: McFarland & Company, 2009): 175]; however, Wright frequently exhibits open and unapologetic hostility to authorship skeptics and is far from “neutral” when he calls those with whom he disagrees “anti-shakespeareans,” “cultists,” “neurotics” and “fanatics.”

- Wright, Louis B. The Folger Library: Two Decades of Growth—An Informal Account, (Charlottesville, VA: University Press of Virginia, 1968), 202.

- 56. Crinkley, “New Perspectives.”

- 57. Crinkley, “New Perspectives,” 515.

- Marx, Bill. “Fuse Commentary: Not Just Shakespeare—‘Anonymous’ Wrongs Ben Jonson As Well.” November 8, 2011. Accessed July 7, 2015.

- Macbeth, 2.3.

- “Library Bill of Rights,” American Library Association, accessed June 20, 2015. Emphasis added.

- “Interpretations of the Library Bill of Rights,” American Library Association, accessed June 20, 2015.