Bob Meyers on Shakespeare’s Politics in Washington Post

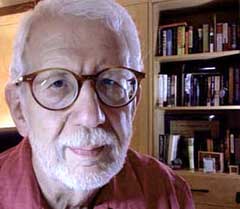

The Washington Post, one of this country’s most influential newspapers, recently published a letter to the editor by Bob Meyers, editor of the SOF’s online series, “How I Became an Oxfordian” (you can read here how Bob himself became an Oxfordian). (Update: Bob, who years ago was a Washington Post reporter, later served on the SOF Board of Trustees and twice as SOF President.)

The letter is a response to a review of Stephen Greenblatt’s book, Tyrant. Bob’s letter deftly summarizes Shakespeare’s views on politics, as demonstrated in the plays, and ends with a subtle question, musing on how the son of illiterate parents learned so much about politics. How indeed?

As Bob commented, regarding the publication of his letter: “This is actually the embodiment of my talk in Boston two years ago — keep it short, simple and reference the text as printed.” This is good advice for letters-to-the-editor writers.

Following is the text of Bob’s letter:

Shakespeare’s political beliefs

Eliot A. Cohen wrote in “Political insights from the Bard for the Trump age” [Book World, May 13], a review of Stephen Greenblatt’s book Tyrant, “We know so little about Shakespeare’s political views because he left virtually nothing behind to tell us what they were.”

In fact, Shakespeare left us more than three dozen plays in which he showed and told us exactly what he thought about politics, writ large and small. Monarchies succeed when the king is on his throne, often battling ambitious underlings (Parts 1 and 2 of “Henry IV”). He consistently favored that stable world knowing that chaos results from the actual or planned overthrow of the king (“Richard II”). He showed us that political disaster parallels personal disruption (“King Lear”). He showed us how a fearless leader is needed to inspire and lead (“Henry V”) and that reconciliation can calm a troubled soul and nation (“The Winter’s Tale”). And it’s not just in the histories and tragedies that we are shown Shakespeare’s worldview; in “A Midsummer Night’s Dream,” social harmony is restored only when the king and queen of the fairies, Oberon and Titania, are reconciled.

It’s all there, clearly and beautifully stated. The only question is how a lad from the countryside, with illiterate parents and children, could learn how the royal court system worked in England’s semi-closed society, often writing with references to historical works that hadn’t yet been translated into English.

Bob Meyers, Alexandria

Membership dues cover only a fraction of our budget, including all our research, preservation and programming. Please support the SOF by making a gift today!

Blue Boar Tavern: Wassail Q&A

Tuesday Dec. 17, 8pm E / 5pm P

Sign up below for event invites!