By: Dorothea Dickerman

“These our actors,

“These our actors,

As I foretold you, were all spirits and

Are melted into air, into thin air:

And, like the baseless fabric of this vision,

The cloud-capp’d towers, the gorgeous palaces,

The solemn temples, the great globe itself,

Ye all which it inherit, shall dissolve.”

The Tempest, IV, i

After four years of construction and $80.5 million, there is much to celebrate about the newly renovated Folger Shakespeare Library on Capitol Hill in Washington, D.C., adjacent to the Library of Congress and the US Supreme Court. The building, including its intimate Elizabethan-inspired theater and non-circulating library which houses an extraordinary collection of 15th century to modern works and artifacts focused on early modern Britain and Europe and the writer known as William Shakespeare, have been closed during the renovation. I attended the Folger’s Grand Opening on June 21, 2024.

The Folger’s committed library staff used the interval to substantially upgrade and expand the digitalization of the collection. In addition to ever-ready online support during the four years the library was closed, the staff had reached out previously to existing readers to walk us through the new online research platform, OpenAthens, which will soon have all of the Folger’s digitalized resources available under one account and one log-in. They also updated us on what changes to expect during in-person visits when the library reopens in the coming days.

The exterior of the 1932 building gleams alabaster white. The outside staircases ascending to its theater and library wings from street level remain intact. Bees buzz contentedly in the manicured garden under the Puck statue’s watchful eye. What is new architecturally is that the area formerly occupied by subterranean stacks in a labyrinthine, frigid rabbit warren of passages and shelves has been transformed into a new below-grade museum, accessible through additional side entrances. More on the museum in a moment. Let’s explore the interior physical environment first.

The exterior of the 1932 building gleams alabaster white. The outside staircases ascending to its theater and library wings from street level remain intact. Bees buzz contentedly in the manicured garden under the Puck statue’s watchful eye. What is new architecturally is that the area formerly occupied by subterranean stacks in a labyrinthine, frigid rabbit warren of passages and shelves has been transformed into a new below-grade museum, accessible through additional side entrances. More on the museum in a moment. Let’s explore the interior physical environment first.

The first floor spine of the building, the Great Hall, which connects the theater and the library wings was previously the Folger’s primary exhibit space. It has become an enlightened community living room, with a café, comfy social seating under the daylight now permitted to cascade from the Hall’s tall windows since precious exhibition items have moved below ground. The jewel-box theater has been renovated slightly but the awkward side facing-seats along the walls remain. While still the neck-craning “cheap seats” for modern groundlings, they are an improvement for anyone recalling that the Folger’s theater seats were once as hard as church pews.

The original paneled half of the double reading room, open for visitor strolling during the Grand Reopening, but not yet for researchers, looks much the same. Readers will be able to return to their favorite haunts shortly. Formerly, a formal application, accompanied by two academic recommendations and a personal statement specifying the applicant’s field of interest, was necessary to obtain in-person access to the Folger’s collection. That restriction has now been lifted and access to the reading room and the open stacks will be available to anyone who registers. As always, restricted materials require either circulation desk request or pre-ordering on line. The librarians assure me that you no longer need a down jacket, mittens and possibly a scarf in the Folger’s reading rooms, but a sweater or a jacket is advisable. Happily, the locker room now has new lockers that work, a sink and refrigerator. Traditional restrictions on what may and may not enter the reading rooms remain.

The original paneled half of the double reading room, open for visitor strolling during the Grand Reopening, but not yet for researchers, looks much the same. Readers will be able to return to their favorite haunts shortly. Formerly, a formal application, accompanied by two academic recommendations and a personal statement specifying the applicant’s field of interest, was necessary to obtain in-person access to the Folger’s collection. That restriction has now been lifted and access to the reading room and the open stacks will be available to anyone who registers. As always, restricted materials require either circulation desk request or pre-ordering on line. The librarians assure me that you no longer need a down jacket, mittens and possibly a scarf in the Folger’s reading rooms, but a sweater or a jacket is advisable. Happily, the locker room now has new lockers that work, a sink and refrigerator. Traditional restrictions on what may and may not enter the reading rooms remain.

All of this is good news.

But turn from the reading room down the now-unadorned hallway towards the Founders Room, which for years contained a 16th century table across which two famous faces on canvas stared eye-to-eye, and you will find they are no longer there. Instead impersonal modern Danish tables and chairs populate the bare-walled space, part of the newly designated conference rooms.

One of those missing paintings, a copy of the Queen Elizabeth “Sieve” Painting, has been retired. The excellent news is that, due to the climate controls installed during the renovation, the glorious and gorgeous original of the Sieve Painting, unseen for years, now hangs somewhat obscurely located in the new Shakespeare Exhibition Hall on the lower level.

One of those missing paintings, a copy of the Queen Elizabeth “Sieve” Painting, has been retired. The excellent news is that, due to the climate controls installed during the renovation, the glorious and gorgeous original of the Sieve Painting, unseen for years, now hangs somewhat obscurely located in the new Shakespeare Exhibition Hall on the lower level.

The other painting missing from the Founders’ Room is, of course, the “Ashbourne Portrait”. There is evidence that this 3/4ths length portrait of a man in costly black 1590s garb, with obvious thick layers of overpainting that slapped a large frontal bald spot over his full head of curly hair (which shows through the paint), his signet ring and crest, and the painting’s date, is of Edward de Vere, 17th Earl of Oxford. Having previously identified the sitter as “William Shakespeare”, and then later, tentatively as a mayor of London, the Folger has never formally identified the sitter as Oxford. However, its former position as the only other painting in the Founders’ Room, directly opposite the Queen’s portrait, always lead me to believe that the Folger knows it is Oxford, and by some desire to hedge bets, in the event incontrovertible evidence surfaces, gave it a position of honor because someone at the Folger knows that Oxford is William Shakespeare.

I asked several members of the hospitable and friendly Folger staff, as they mingled with the day’s ebullient guests, for the location of the Ashbourne and other paintings that formerly lined the hallway and reading room walls. No one had any idea. The consistent answer I received was that the paintings had been stored during the renovation for safety and that no plan has been announced about which paintings will be rehung or where or when. Some paintings might be loaned to other collections.

The face that the Folger now turns to the world is exhibited in its new below-grade museum, a destination in this city of destination museums. Symbolized by the rainbow-colored “F” of the Folger’s Instagram logo, the Folger is now the democratization of the brand of Shakespeare. According to the Folger, Shakespeare belongs to each of us in our individual ways, as we want to imagine him, relative to ourselves.

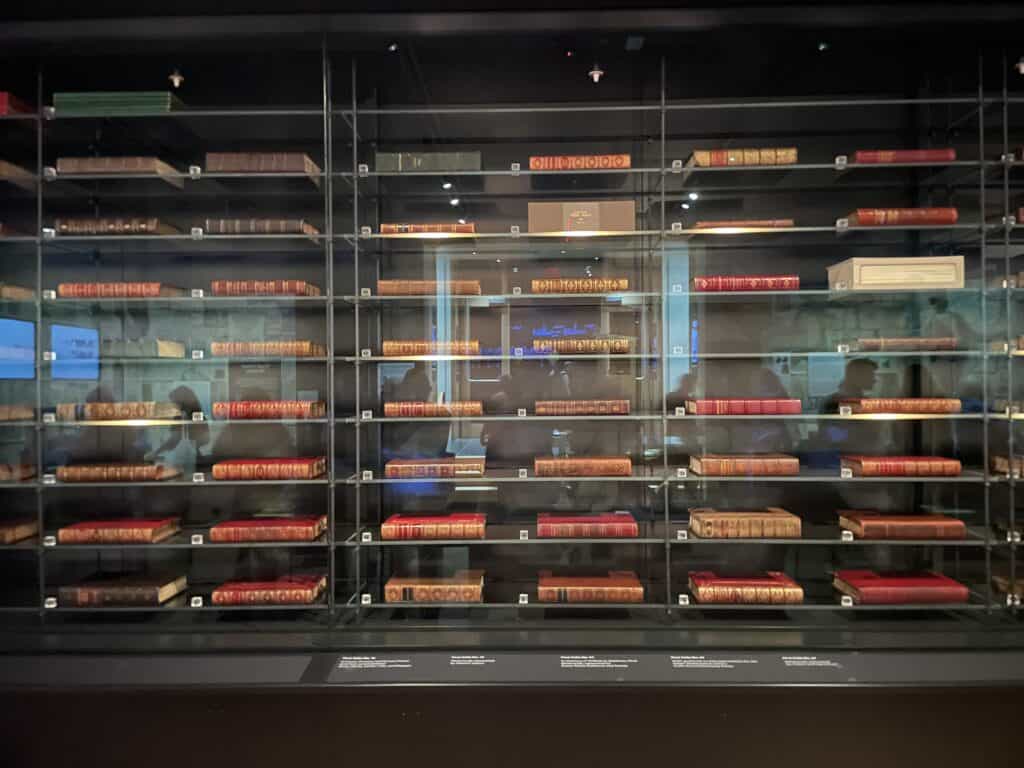

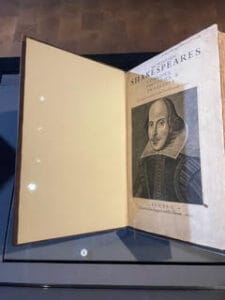

The Shakespeare Exhibition Hall opens with a large wall plaque: “Shakespeare? He was then and there and he is here and now. Discoveries Await!”. But of the man himself, where he lived, the course of his development as a writer, the means by which he garnered the wisdom of his age and the prior two millennia, or the story of his connection to the impressive wall of 82 First Folios, lying obediently on their sides in their transparent vault, like so many bricks in a fortress, or perhaps the American Cliffs of Dover, there is almost nothing.

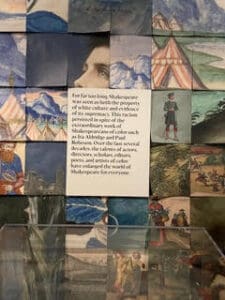

A series of plaques bearing short explanatory texts in large font hang at intervals along walls papered in patchwork copies of works in the Folger’s collection, reminiscent of once-popular bathroom walls papered with covers of The New Yorker. Unfortunately, more than one plaque contains factual errors. For example, this one which overlooks that Ben Jonson’s First Folio, titled The Workes of Beniamin Ionson, containing 9 of his plays, was published in 1616, seven years before Shakespeare’s First Folio of 1623. Jonson’s First Folio resides in the Folger’s vault.

A series of plaques bearing short explanatory texts in large font hang at intervals along walls papered in patchwork copies of works in the Folger’s collection, reminiscent of once-popular bathroom walls papered with covers of The New Yorker. Unfortunately, more than one plaque contains factual errors. For example, this one which overlooks that Ben Jonson’s First Folio, titled The Workes of Beniamin Ionson, containing 9 of his plays, was published in 1616, seven years before Shakespeare’s First Folio of 1623. Jonson’s First Folio resides in the Folger’s vault.

Jonson’s famous “To the Reader” preface, giving instructions to look not at the proffered engraved portrait but in the book itself to find the Bard, is missing from the Shakespeare Folio that that Folger has chosen to display open, as if Jonson were purposefully being erased not only from the Folio itself and its history, but from his own history.

Other plaques inform us that: “In London of the 1590s, Shakespeare was a writer and an actor shouting to be heard in a rowdy theater” and goes on to say he started a riot in 1840s New York, kept miners going in the California Gold Rush and in 1950s Washington inspired a groundbreaking production at Howard University. “In life, Shakespeare was a writer, an actor, and a businessperson, but over the centuries he has come to represent even more. . . his work and words, all part of his story – and ours.” We are Shakespeare now. His life story has now become our stories. He is Brand: Shakespeare for Everyone.

In short, the man himself has atomized, “melted into air, into thin air” as he wrote in The Tempest. Like Edward de Vere on June 24, 1604, the Bard is ceasing to be in the same way he previously was. He is now an idea, an “icon”, a “spark”, a “spirit”, according to the Folger’s plaques. Fill in his actual life as you will.

Contemplating why the Folger had softened so much on the identity of the Bard, whose paltry life story now appears in carefully crafted but unlinked snippets throughout the Shakespeare Exhibition Hall, I sampled some of the delectable bites on display hinting at the Folger’s true treasure trove, the banquet in its vaults of manuscripts, printed books, paintings, furniture and theater memorabilia. Among many other items, the Folger has chosen currently to display a 1597 first quarto of Romeo and Juliet, “Robert Greene’s” Groats-worth of Witte open to the page on which appear the phrases “upstart crow” and “Shake-scene” (accompanied by declaration that this evidences the man from Stratford’s presence in 1592 London). https://shakespeareoxfordfellowship.org/greenes-groatsworth-shakespeares-biography/. Richard Stoney’s diary recording his purchase of Venus and Adonis, the “Pavier Quartos” https://shakespeareoxfordfellowship.org/pembroke-intervention-pavier-quartos/ and Holinshed’s Chronicles accompanied by the text “Shakespeare Goes in Search of an Idea, 1577”, intimating that the precocious 13-year-old Stratford lad was already researching history plays he would write 20 years later.

Interspersed among these items more wall plaques tell us, for example, “No rich patron decreed that this folio should be made: just two of Shakespeare’s friends.” While technically true that there was no one rich patron, missing is the fact that according to the First Folio itself, those “two friends” were “an incomparable pair of brethren” specifically named as the very wealthy Earls of Pembroke and Montgomery. They had also married or been betrothed to two of Oxford’s daughters.

Peering sideways at the spines of display samples of the Folger’s vast collection of period books published in Antwerp, Venice, Rome and Paris in the Rare Book & Manuscript Exhibition Hall, I acknowledged to myself that there is no doubt that interest in Shakespeare has been steeply on the decline in recent years. His words take effort and historical context to comprehend, which is difficult to sustain in a society in which reading skills and knowledge of history are rapidly diminishing. In many ways the new Folger fights the good fight against that decline. Commendably, to save itself to some extent, but also to save the work, the Folger has spent millions of dollars and countless human hours to make “Shakespeare”, as it defines that word, relevant and popular again. Backing away from the man from Stratford certainly hedges the institution’s bets should it need to pivot suddenly to recognize a new individual as the Bard. But I kept thinking something more was at play here.

A single exhibit case and plaque nodded to the founders of the Folger Library, Henry and Emily Folger, although Henry’s bust still occupies its niche in the Great Hall, hungrily overlooking the café dessert display at the reception. https://shakespeareoxfordfellowship.org/looking-not-on-his-picture-but-his-books-two-new-histories-of-folgers-quest-for-first-folios-shed-unintended-light-on-the-authorship-question/

A few children and parents tried out the interactive games and replica of an early modern printing press. Several exhibits highlighted colonization of the new world and the underappreciated role persons of color have played in the development of who Shakespeare has come to be today. Mark Twain’s Huckleberry Finn winked at me from inside a display case, as if alluding to the fact that “Mark Twain” was as much a pseudonym as “William Shakespeare”. Samuel Clemens famously doubted the Stratford grain dealer’s identity as the Bard. Attendees perused well-stocked shelves in the larger, brighter museum shop.

A few children and parents tried out the interactive games and replica of an early modern printing press. Several exhibits highlighted colonization of the new world and the underappreciated role persons of color have played in the development of who Shakespeare has come to be today. Mark Twain’s Huckleberry Finn winked at me from inside a display case, as if alluding to the fact that “Mark Twain” was as much a pseudonym as “William Shakespeare”. Samuel Clemens famously doubted the Stratford grain dealer’s identity as the Bard. Attendees perused well-stocked shelves in the larger, brighter museum shop.

It was not until I emerged back outside into the Folger’s Elizabethan garden under the midsummer sun and white-capped clouds that the answer to my perplexing question became apparent. Chiseled right under the feet of the statue of Puck are these words from The Tempest:

“Lord, what fooles these mortals be.”

“Lord, what fooles these mortals be.”

I am a native-born Washingtonian. How foolish could I be? I was standing in the middle of it.

The Folger Shakespeare Library is located in epicenter of the most political city on the globe, right next to the temple-like edifices of the Supreme Court and the Library of Congress, a stone’s throw from both Houses of Congress in the capitol of the United States of America. The Folger’s gleaming façade even resembles those more palatial facades. Distancing itself from the human Bard and democratizing “Shakespeare” as a brand, an “icon”, a “spark”, a “spirit” allows the Folger to float more freely on the ever-changing tides of the political ocean. What if credible information came out that the man from Stratford was even more villainous than the hoarder of grain during famines and habitual bringer of lawsuits against his neighbors that historical evidence proves he was? What if disreputable secrets about Henry Folger lie in the vaults? What if the Bard was indeed a superbly-educated, well-connected and widely-travelled nobleman? Best democratize “Shakespeare” as a brand and avoid those political risks.

One of the plaques in the Shakespeare Exhibition Hall frames the question thus: “Who was Shakespeare? What is he to you? A hero? An icon? The name on a book you never wanted to open?”. If, according to the Folger, “Shakespeare” has become that brand, that “icon”, “spark”, “spirit”, and “connected by his work and words, all part of his story – and ours”, then Shakespeare can be anyone.

Shakespeare can be you, or me, or a woman, or even Edward de Vere, 17th Earl of Oxford.

Dorothea can be reached through her website: https://www.dorotheadickerman.com